Cave

A cave or cavern is a natural underground space large enough for a human to enter. Some people[who?] suggest that the term cave should only apply to cavities that have some part that does not receive daylight; however, in popular usage, the term includes smaller spaces like sea caves, rock shelters, and grottos.

Speleology is the science of exploration and study of all aspects of caves and the environment which surrounds the caves. Exploring a cave for recreation or science may be called caving, potholing, or, in Canada and the United States, spelunking (see Caving).

Types and formation

The formation and development of caves is known as speleogenesis. Caves are formed by various geologic processes. These may involve a combination of chemical processes, erosion from water, tectonic forces, microorganisms, pressure, atmospheric influences, and even digging.

Most caves are formed in limestone by dissolution.

Solutional cave

Solutional caves are the most frequently occurring caves and such caves form in rock that is soluble, such as limestone, but can also form in other rocks, including chalk, dolomite, marble, salt, and gypsum. Rock is dissolved by natural acid in groundwater that seeps through bedding-planes, faults, joints etc. Over geological epochs cracks expand to become caves or cave systems.

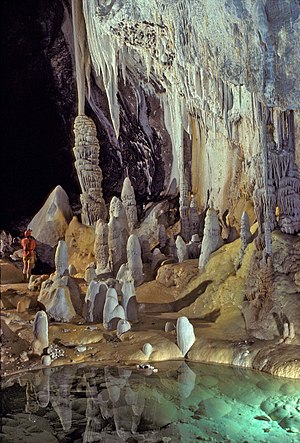

The largest and most abundant solutional caves are located in limestone. Limestone dissolves under the action of rainwater and groundwater charged with H2CO3 (carbonic acid) and naturally occurring organic acids. The dissolution process produces a distinctive landform known as karst, characterized by sinkholes, and underground drainage. Limestone caves are often adorned with calcium carbonate formations produced through slow precipitation. These include flowstones, stalactites, stalagmites, helictites, soda straws and columns. These secondary mineral deposits in caves are called speleothems.

The portions of a solutional cave that are below the water table or the local level of the groundwater will be flooded.[1]

The world's most spectacularly decorated cave is generally regarded to be Lechuguilla Cave in New Mexico. Lechuguilla and nearby Carlsbad Cavern are now believed to be examples of another type of solutional cave. They were formed by H2S (hydrogen sulfide) gas rising from below, where reservoirs of oil give off sulfurous fumes. This gas mixes with ground water and forms H2SO4 (sulfuric acid). The acid then dissolves the limestone from below, rather than from above, by acidic water percolating from the surface.

Primary cave

Some caves are formed at the same time as the surrounding rock. These are sometimes called primary caves.

Lava tubes are formed through volcanic activity and are the most common 'primary' caves. The lava flows downhill and the surface cools and solidifies. The hotter lava continues to flow under that crust, and if most of the liquid lava beneath the crust flows out, a hollow tube remains, thus forming a cavity. Examples of such caves can be found on the Canary Islands, Hawaii, and many other places. Kazumura Cave near Hilo is a remarkably long and deep lava tube; it is 65.6 km long (40.8 mi).

Lava caves, include but are not limited to lava tubes. Other caves formed through volcanic activity include rift caves, lava mold caves, open vertical volcanic conduits, and inflationary caves.

Sea cave or littoral cave

Sea caves are found along coasts around the world. A special case is littoral caves, which are formed by wave action in zones of weakness in sea cliffs. Often these weaknesses are faults, but they may also be dykes or bedding-plane contacts. Some wave-cut caves are now above sea level because of later uplift. Elsewhere, in places such as Thailand's Phang Nga Bay, solutional caves have been flooded by the sea and are now subject to littoral erosion. Sea caves are generally around 5 to 50 metres (16 to 164 ft)* in length but may exceed 300 metres (980 ft)*.

Corrasional cave or erosional cave

Corrasional or erosional caves are those that form entirely by erosion by flowing streams carrying rocks and other sediments. These can form in any type of rock, including hard rocks such as granite. Generally there must be some zone of weakness to guide the water, such as a fault or joint. A subtype of the erosional cave is the wind or aeolian cave, carved by wind-born sediments. Many caves formed initially by solutional processes often undergo a subsequent phase of erosional or vadose enlargement where active streams or rivers pass through them.

Glacier cave

Glacier caves occur in ice and under glaciers and are formed by melting. They are also influenced by the very slow flow of the ice, which tends to close the caves again. (These are sometimes called ice caves, though this term is properly reserved for caves that contain year-round ice formations).

Fracture cave

Fracture caves are formed when layers of more soluble minerals, such as gypsum, dissolve out from between layers of less soluble rock. These rocks fracture and collapse in blocks of stone.

Talus cave

Talus caves are the openings between rocks that have fallen down into a pile, often at the bases of cliffs (called "talus").

Anchihaline cave

Anchihaline caves are caves, usually coastal, containing a mixture of freshwater and saline water (usually sea water). They occur in many parts of the world, and often contain highly specialized and endemic faunas.

Patterns

- Branchwork caves resemble surface dentritic stream patterns; they are made up of passages that join downstream as tributaries. Branchwork caves are the most common of cave patterns and are formed near sinkholes where groundwater recharge occurs. Each passage or branch is fed by a separate recharge source and converges into other higher order branches downstream.[2]

- Angular Network caves form from intersecting fissures of carbonate rock that have had fractures widened by chemical erosion. These fractures form high, narrow, straight passages that persist in widespread closed loops.[2]

- Anastomotic caves largely resemble surface braided streams with their passages separating and then meeting further down drainage. They usually form along one bed or structure, and only rarely cross into upper or lower beds.[2]

- Spongework caves are formed as solution cavities are joined by mixing of chemically diverse water. The cavities form a pattern that is three-dimensional and random, resembling a sponge.[2]

- Ramiform caves form as irregular large rooms, galleries, and passages. These randomized three-dimensional rooms form from a rising water table that erodes the carbonate rock with hydrogen-sulfide enriched water.[2]

Geographic distribution

Caves are found throughout the world, but only a portion of them have been explored and documented by cavers. The distribution of documented cave systems is widely skewed toward countries where caving has been popular for many years (such as France, Italy, Australia, the UK, the United States, etc.). As a result, explored caves are found widely in Europe, Asia, North America, and Oceania but are sparse in South America, Africa, and Antarctica. This is a great generalization, as large expanses of North America and Asia contain no documented caves, whereas areas such as the Madagascar dry deciduous forests and parts of Brazil contain many documented caves. As the world’s expanses of soluble bedrock are researched by cavers, the distribution of documented caves is likely to shift. For example, China, despite containing around half the world's exposed limestone - more than 1,000,000 square kilometres (390,000 sq mi)* - has relatively few documented caves.

Record lengths, depths, pitches and volumes

- The cave system with the greatest total length of surveyed passage is Mammoth Cave (Kentucky, USA) at 591 kilometres (367 mi)* in length. This record is unlikely to be surpassed in the near future, as the next most extensive known cave is Jewel Cave near Custer, South Dakota, at 225 kilometres (140 mi)*.[3]

- The longest surveyed underwater cave is the Ox Bel Ha Cave System in Yucatán, Mexico at 180 km (110 mi).[3] The record has been exchanged several times with Sistema Sac Actun, currently at 172 kilometres (107 mi)*.

- The deepest known cave (measured from its highest entrance to its lowest point) is Voronya Cave (Abkhazia), with a depth of 2,191 metres (7,188 ft)*.[4] This was the first cave to be explored to a depth of more than 2 kilometres (1.2 mi)*. (The first cave to be descended below 1 kilometre (0.62 mi)* was the famous Gouffre Berger in France.) The Illyuzia-Mezhonnogo-Snezhnaya cave in Abkhazia, (1,753 metres or 5,751 feet*) and the Lamprechtsofen Vogelschacht Weg Schacht in Austria (1,632 metres or 5,354 feet*) are the current second- and third-deepest caves. The deepest cave record has changed several times in recent years.

- The deepest vertical shaft in a cave is 603 metres (1,978 ft)* in Vrtoglavica Cave in Slovenia. The second deepest is Patkov Gušt at 553 metres (1,814 ft)* in the Velebit mountain, Croatia.

- The largest room ever discovered is the Sarawak chamber, in the Gunung Mulu National Park (Miri, Sarawak, Borneo, Malaysia), a sloping, boulder strewn chamber with an area of approximately Template:Gconvert and a height of 80 metres (260 ft)*. The nearby Clearwater Cave System is believed to be the world's largest cave by volume, with a calculated volume of 30,347,540 m3.

- The largest passage ever discovered is in the Son Doong Cave in Phong Nha-Ke Bang National Park in Quang Binh Province, Vietnam. Explored by joint Vietnamese-British cave scientists of the British Cave Research Association, it is 4.6 km (2.9 mi) in length, 80 m (260 ft) high and wide over most of its length, but over 140 m (460 ft) high and wide for part of its length.[5]

Ecology

Cave-inhabiting animals are often categorized as troglobites (cave-limited species), troglophiles (species that can live their entire lives in caves, but also occur in other environments), trogloxenes (species that use caves, but cannot complete their life cycle wholly in caves) and accidentals (animals not in one of the previous categories). Some authors use separate terminology for aquatic forms (e.g., stygobites, stygophiles, and stygoxenes).

Of these animals, the troglobites are perhaps the most unusual organisms. Troglobitic species often show a number of characteristics, termed troglomorphies, associated with their adaptation to subterranean life. These characteristics may include a loss of pigment (often resulting in a pale or white coloration), a loss of eyes (or at least of optical functionality), an elongation of appendages, and an enhancement of other senses (such as the ability to sense vibrations in water). Aquatic troglobites (or stygobites), such as the endangered Alabama cave shrimp, live in bodies of water found in caves and get nutrients from detritus washed into their caves and from the feces of bats and other cave inhabitants. Other aquatic troglobites include cave fish, the Olm, and cave salamanders such as the Texas Blind Salamander.

Cave insects such as Oligaphorura (formerly Archaphorura) schoetti are troglophiles, reaching 1.7 millimetres (0.067 in)* in length. They have extensive distribution and have been studied fairly widely. Most specimens are female but a male specimen was collected from St Cuthberts Swallet in 1969.

Bats, such as the Gray bat and Mexican Free-tailed Bat, are trogloxenes and are often found in caves; they forage outside of the caves. Some species of cave crickets are classified as trogloxenes, because they roost in caves by day and forage above ground at night.

Because of the fragile nature of the cave ecosystem, and the fact that cave regions tend to be isolated from one another, caves harbor a number of endangered species, such as the Tooth cave spider, Liphistiidae Liphistius trapdoor spider, and the Gray bat.

Caves are visited by many surface-living animals, including humans. These are usually relatively short-lived incursions, due to the lack of light and sustenance.

Archaeological and cultural importance

Throughout history, primitive peoples have made use of caves for shelter, burial, or as religious sites. Since items placed in caves are protected from the climate and scavenging animals, this means caves are an archaeological treasure house for learning about these people. Cave paintings are of particular interest. One example is the Great Cave of Niah, in Malaysia, which contains evidence of human habitation dating back 40,000 years.[6] Another, the Diepkloof Rock Shelter in South Africa contains evidence of human habitation and use of symbols dating back 60,000 years.[7]

In the animal kingdom, caves offer shelter, including uses such as maternity dens.

In Germany some experts found signs of cannibalism in the caves at the Hönne.

Caves are also important for geological research because they can reveal details of past climatic conditions in speleothems and sedimentary rock layers.

Caves are frequently used today as sites for recreation. Caving, for example, is the popular sport of cave exploration. For the less adventurous, a number of the world's prettier and more accessible caves have been converted into show caves, where artificial lighting, floors, and other aids allow the casual visitor to experience the cave with minimal inconvenience. Caves have also been used for BASE jumping and cave diving. The book Caverns of Magic by Hal G. P. Colebatch surveys some of the instances of cave stories in literature and mythology.

Caves are also used for the preservation or aging of wine and cheese. The constant, slightly chilly temperature and high humidity that most caves possess makes them ideal for such uses.

World's longest caves

- Mammoth Cave, Kentucky[3]

- Jewel Cave, South Dakota[3]

- Optymistychna Cave, Ukraine[3]

- Wind Cave, South Dakota[3]

- Lechuguilla Cave, New Mexico[3]

See also

- Cave Conservancies

- Cave Research Foundation

- Cenote

- Flowstone

- List of caves

- National Speleological Society

- Pit cave

- Speleology

- Speleothem

- Subterranean lake

- Subterranean river

References

- ^ John Burcham. "Learning about caves; how caves are formed". Journey into amazing caves. Project Underground. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Easterbrook, Don, 1999, Surface Processes and Landforms [2nd edition], New Jersey, Prentice Hall, pp. 207

- ^ a b c d e f g World’s Longest Caves List from The National Speleological Society

- ^ World's Deepest Caves List from The National Speleological Society

- ^ Owen, James (2009-07-04). "World's Biggest Cave Found in Vietnam". National Geographic News. National Geographic Society. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ National Geographic. James Shreeve. "The Greatest Journey". March 2006.

- ^ Texier PJ, Porraz G, Parkington J, Rigaud JP, Poggenpoel C, Miller C, Tribolo C, Cartwright C, Coudenneau A, Klein R, Steele T, Verna C. (2010). "A Howiesons Poort tradition of engraving ostrich eggshell containers dated to 60,000 years ago at Diepkloof Rock Shelter, South Africa". Proceedings of the National Acadademy of Science U S A. 107: 6180–6185. doi:10.1073/pnas.0913047107 PMID 20194764

External links

- Australian Speleological Federation (ASF), AU

- British Caving Association (BCA), UK

- The Mulu Caves Project, A British-Malaysian collaboration to explore the caves of the Gunung Mulu National Park, Sarawak

- Classification of Caves A list of cave types with links to further information

- Journal of Cave and Karst Studies

- National Speleological Society (NSS), US

- International Union of Speleology (UIS).

- Speleological Abstract (SA/BBS) An annual review of the world's speleological literature.

- The Virtual Cave Large educational site with numerous photographs of various types of caves and cave formations and descriptions of how they form.

- cave-biology.org Cave biology (biospeleology) in India.

- Biospeleology; The Biology of Caves, Karst, and Groundwater, by Texas Natural Science Center, The University of Texas at Austin and the Missouri Department of Conservation.

- Tour Caves A Google Map of Commercial Tour Caves in the US.

- French Caves List of Commercial Caves in France.

- Caves of Croatia List and details about longest and deepest caves and pits in Croatia.

- Cathedral Cave Preserve A privately owned speleological research and educational park. US

- The latest news from the caving scene.

- World Cave Database