Battle of Taegu

35°52′N 128°36′E / 35.867°N 128.600°E Template:Fix bunching

| Battle of Taegu | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of Pusan Perimeter | |||||||

U.S. 1st Cavalry Division soldiers fire at North Korean troops crossing the Naktong River | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 4 Divisions | 5 Divisions | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

200 killed 400 wounded | 3,700+ killed and wounded | ||||||

The Battle of Taegu was an engagement between United Nations and North Korean forces early in the Korean War, with fighting continuing from August 5–20, 1950 around the city of Taegu, South Korea. It was a part of the Battle of Pusan Perimeter, and was one of several large engagements fought simultaneously. The battle ended in a victory for the United Nations after their forces were able to drive off an offensive by North Korean divisions attempting to cross the Naktong River and assault the city.

Five North Korean Army divisions massed around the city preparing to cross the Naktong River and assault it from the north and west. Defending the city were the U.S. 1st Cavalry Division and the ROK II Corps. In a series of engagements, each of the North Korean divisions attempted to cross the Naktong and attack the defending forces. The success of these attacks varied by region, but attacks in the 1st Cavalry Division sector were repulsed and the attacks in the South Korean sector were more successful.

During the battle, however, North Korean troops were able to surprise US troops on Hill 303 and capture them. Late in the battle, these troops were machine gunned in the Hill 303 massacre. Despite these things, the United Nations forces were successful in driving most of the North Korean off, but the decisive battle to secure the city would occur during the Battle of the Bowling Alley.

Background

Outbreak of war

Following the invasion of the Republic of Korea (South Korea) by its northern neighbor, the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea) and the subsequent outbreak of the Korean War on June 25, 1950, the United Nations decided to enter the conflict on behalf of South Korea. The United States, a member of the UN, simultaneously committed ground forces to the Korean peninsula with the goal of fighting back the North Korean invasion and preventing South Korea from collapsing. However, US forces in the Far East had been steadily decreasing since the end of World War II, five years earlier, and at the time the closest forces were the 24th Infantry Division, headquartered in Japan. The division was understrength, and most of its equipment was antiquated due to reductions in military spending. Regardless, the 24th was ordered to South Korea.[1]

The 24th Infantry Division was the first US unit sent into Korea with the mission to take the initial "shock" of North Korean advances, delaying much larger North Korean units to buy time to allow reinforcements to arrive.[2] The division was consequently alone for several weeks as it attempted to delay the North Koreans, making time for the 1st Cavalry and the 7th and 25th Infantry Divisions, along with other Eighth Army supporting units, to move into position.[2] Advance elements of the 24th were badly defeated in the Battle of Osan on July 5, the first encounter between American and North Korean forces.[3] For the first month after the defeat at Osan, the 24th Infantry Division was repeatedly defeated and forced south by superior North Korean numbers and equipment.[4][5] The regiments of the division were systematically pushed south in engagements around Chochiwon, Chonan, and Pyongtaek.[4] The 24th made a final stand in the Battle of Taejon, where it was almost completely destroyed but delayed North Korean forces until July 20.[6] By that time, the Eighth Army's force of combat troops were roughly equal to North Korean forces attacking the region, with new UN units arriving every day.[7]

North Korean advance

With Taejon captured, North Korean forces began surrounding the Pusan Perimeter from all sides in an attempt to envelop it. The 4th and 6th North Korean Infantry Divisions advanced south in a wide flanking maneuver. The two divisions attempted to envelop the UN's left flank, but became extremely spread out in the process. They advanced on UN positions with armor and superior numbers, repeatedly defeating US and South Korean forces and forcing them further south.[8]

American forces were pushed back repeatedly before finally halting the North Korean advance in a series of engagements in the southern section of the country. Forces of the 3rd Battalion, 29th Infantry, newly arrived in the country, were wiped out at Hadong in a coordinated ambush by North Korean forces on July 27, opening a pass to the Pusan area.[9][10] Soon after, North Korean forces took Chinju to the west, pushing back the US 19th Infantry Regiment and leaving routes to the Pusan open for more North Korean attacks.[11] US formations were subsequently able to defeat and push back the North Koreans on the flank in the Battle of the Notch on August 2. Suffering mounting losses, the Korean People's Army force in the west withdrew for several days to re-equip and receive reinforcements. This granted both sides a reprieve to prepare for the attack on the Pusan Perimeter.[12][13]

Taegu

In the meantime, Eighth Army commander Lieutenant General Walton Walker had established Taegu as the Eighth Army's headquarters.[14] Right at the center of the Pusan Perimeter, Taegu stood at the entrance to the Naktong River valley, an area where North Korean forces could advance in large numbers in close support. The natural barriers provided by the Naktong River to the south and the mountainous terrain to the north converged around Taegu, which was also the major transportation hub and last major South Korean city aside from Pusan itself to remain in UN hands.[15] From south to north, the city was defended by the US 1st Cavalry Division, and the ROK 1st Division and ROK 6th Division of ROK II Corps. 1st Cavalry Division was spread out along a long line along the Naktong River to the south, with its 5th Cavalry and 8th Cavalry regiments holding a 24,000 metres (79,000 ft) line along the river south of Waegwan, facing west. The 7th Cavalry held position to the east in reserve, along with artillery forces, ready to reinforce anywhere a crossing could be attempted. The ROK 1st Division held a northwest-facing line in the mountains immediately north of the city while the ROK 6th Division held position to the east, guarding the narrow valley holding the Kunwi road into the Pusan Perimeter area.[16]

Five North Korean divisions amassed to oppose the UN at Taegu. From south to north, the 10th,[17] 3rd, 15th, 13th,[18] and 1st Divisions occupied a wide line encircling Taegu from Tuksong-dong and around Waegwan to Kunwi.[19] The North Korean army planned to use the natural corridor of the Naktong valley from Sangju to Taegu as its main axis of attack for the next push south, so the divisions all eventually moved through this valley, crossing the Naktong at different areas along the low ground.[20] Elements of the NK 105th Armored Division also supported the attack.[16][21]

Battle

On the night of August 4/5, the NK 13th Division began crossing the Naktong River at Naktong-ni, 40 miles (64 km) northwest of Taegu. The crossing was not discovered until August 5 when ROK artillery and mortar fire was called on the crossing. Over the course of three nights, North Korean soldiers from the division's three regiments crossed the river in raft or wading, carrying weapons and equipment over their heads. The entire division was across by August 7, and assembling several miles from the ROK 1st Division's prepared defenses.[16]

At the same time, the NK 1st Division crossed the river by barge between Hamch'ang and Sangju, in the ROK 6th Division's sector from August 6 to 8. This attack was discovered quickly by American aircraft and the NK 1st Division was immediately engaged by the ROK forces. The two divisions locked in battle around Kunwi until August 17, with the North Korean division facing stubborn resistance and heavy casualties.[16]

Opening moves

ROK troops attacked the 13th Division immediately after it completing its crossing, forcing scattered North Korean troops into the mountains. The division reassembled to the east and launched a concerted night attack, broke the ROK defenses, and began an advance that carried it twenty miles southeast of Naktong-ni on the main road to Taegu. Within a week, the NK 1st and 13th divisions were converging on the Tabu-dong area, about 15 miles (24 km) north of Taegu.[22]

The NK 15th Division, next of the North Korean divisions in line to the south, received 1,500 replacements at Kumch'on on August 5, which brought its strength to about 6,500 men. The next day its 45th Regiment marched northeast toward the Naktong River. The regiment passed through Sonsan on August 7 and crossed the river southeast of that town while under attack by UN aircraft. Once across the river, the regiment headed into the mountains, initially encountering no UN opposition. The other two regiments, the 48th and 50th, departed Kumch'on later and began crossing the Naktong between Indong and Waegwan before dawn of August 8, constructing underwater bridges for their vehicles. The North Koreans supported this crossing by direct tank fire from the west side of the river. These tanks then conducted their own crossing of river during the day. The NK 15th Division seized Hills 201 and 346 on the east side of the river at the crossing site before advancing eastward into the mountains toward Tabu-dong, 7 miles (11 km) away.[22] The next day, ROK 1st Division regained the high ground at the crossing sites, forcing the North Korean forces further eastward into the mountains. From August 12–16 the three regiments of the NK 15th Division united on the east side of the Naktong River in the vicinity of Yuhak-san, 5 miles (8.0 km) east of the crossing site and 3 miles (4.8 km) northwest of Tabu-dong. The NK 13th Division quickly locked in combat on Yuhak-san with the ROK 1st Division.[23][24]

South of Waegwan, two more enemy divisions stood ready to cross the Naktong in a coordinated attack with the divisions to the north.[23] The experienced NK 3rd Division, concentrated in the vicinity of Songju, and the untested NK 10th Division, concentrated in the Koryong area and both had mobilized for attack.[25] These two divisions crossed in the US 1st Cavalry Division's sector. The NK 3rd Division's 7th Regiment started crossing the Naktong about 0300 August 9 near Noch'on, two miles south of the Waegwan bridge.[23] Discovering the crossing, elements of the US 5th Cavalry Regiment directed automatic weapons fire against the North Koreans and called in pre-registered artillery fire on the crossing site.[25] Although the enemy regiment suffered some casualties, the bulk of it reached the east bank safely and moved inland into the hills. 30 minutes later, the 8th and 9th Regiments began crossing the river to the south.[23] The 5th Cavalry Regiment and all its supporting mortars and artillery, now fully alerted, spotted and decimated the two regiments' troops and turned them back to the west bank.[25] Only a small number of North Koreans reached the east side. There, they were either captured or hid until the next night when they recrossed the river.[23]

Triangulation Hill

At dawn on August 9, division commander Major General Hobart R. Gay at 1st Cavalry Division headquarters in Taegu learned of the enemy crossing in his division sector south of Waegwan. As first reports were vague, he decided to withhold action until he learned more about the situation.[26] He quickly learned that around 750 North Korean infantry had gathered on Hill 268, also known as Triangulation hill, which was 3 miles (4.8 km) southeast of Waegwan and 10 miles (16 km) northwest of Taegu.[27] Gay ordered his division to counterattack the enemy gathering to force them across the river. He and Walker believed the attack could be a feint and the North Koreans could be planning a larger attack to the north. Moreover, the hill was important for its proximity to lines of communication. The main Korean north-south highway and the main double-track Seoul-Pusan railroad skirted its base.[26]

At 0930, General Gay ordered the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, to eliminate the enemy penetration. The battalion moved from its bivouac area just outside Taegu, accompanied by five tanks of A Company, 71st Heavy Tank Battalion. This motorized force proceeded to the foot of Hill 268. The 61st Field Artillery Battalion meanwhile shelled the hill heavily.[26]

At 1200 the artillery fired a preparation on Hill 268, and the 1st Battalion then attacked it under orders to continue on southwest to Hill 154. Hill 268 was covered with thick brush 4 feet (1.2 m) and trees eight to 10 feet (3.0 m) high. The day was very hot and many 1st Battalion soldiers collapsed from heat exhaustion during the attack, which was not well coordinated with artillery fire. The North Koreans repulsed the attack. The next morning, August 10, air strikes and artillery preparations rocked Hill 268, devastating the North Korean battalion. That afternoon, Gay ordered five US tanks to move along the Waegwan road until they could fire from the northwest into the reverse slope of the hill. This tank fire caught the North Koreans unprepared as they were hiding from the artillery fire. Trapped between the two fires they started to vacate their positions. An American infantry attack then reached the top of the hill without trouble and the battle was over by 1600. American artillery and mortar fire now shifted westward and cut off the North Korean retreat. White phosphorus shells fired from the 61st Field Artillery Battalion caught North Koreans in a village as they attempted to retreat, and they were routed by American infantry, suffering over 200 killed. That evening the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, reverted to division reserve, and elements of the 5th Cavalry finished securing Hill 268.[28]

The 7th Regiment of the NK 3rd Division had been destroyed on the hill. The 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry suffered 14 men killed, and 48 wounded in the 2-day battle.[28] About 1,000 men of the 7th Regiment had crossed the Naktong to Hill 268, and about 700 of at them became casualties.[27] Artillery and mortars had inflicted most of the crippling casualties on the regiment. After crossing to the east side of the Naktong, the enemy regiment had received no food or ammunition supply.[28] An estimated 300 survivors retreated across the river the night of August 10/11.[27] The NK 3rd Division's attempted crossing of the Naktong south of Waegwan had ended in catastrophe. When the survivors of the 7th Regiment rejoined the division on or about 12 August, the once powerful 3rd Division was reduced to a disorganized unit of some 2,500 men. The North Korean Army placed the division in reserve to be rebuilt by replacements.[27][29]

Yongp'o crossing

The North Korean plan for the attack against Taegu from the west and southwest demanded the NK 10th Division make a coordinated attack with the NK 3rd Division. The 10th Division, so far untested in combat, had started from Sukch'on for the front by rail on July 25. At Chonan it left the trains and continued south on foot through Taejon, arriving at the Naktong opposite Waegwan around August 8. The division was ordered to cross the Naktong River in the vicinity of Tuksong-dong, penetrate east, and cut the UN forces' main supply route from Pusan to Taegu. The division assembled in the Koryong area on 11 August.[29]

Two regiments of the NK 10th Division, the 29th to the south and the 25th to the north, were to make the assault crossing with the 27th Regiment in reserve. The 2nd Battalion, 29th Regiment, was the first unit of the division to cross the river.[30] Its troops waded across undetected during the night of August 11/12, west of Hyongp'ung.[27] It then occupied Hill 265, a northern spur of Hill 409, 2 miles (3.2 km) southwest of Hyongp'ung, and set up machine gun positions. The other two battalions followed it and occupied Hill 409. The North Koreans on Hill 409 soon ambushed a patrol from the 21st Infantry of the US 24th Infantry Division, which was moving north and trying to establish contact with the 7th Cavalry Regiment during the Battle of the Naktong Bulge occurring simultaneously to the south.[30]

Further north, the 25th Regiment started crossing the Naktong at about 0300 on August 12, in the vicinity of Tuksong-dong, on the Koryong-Taegu road. The 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment, covered this crossing site, which was 14 miles (23 km) southwest of Taegu. By daylight, a North Korean force of 300 to 400 had penetrated to Wich'on-dong and 2nd Battalion's H Company engaged it in close combat. In a grenade and automatic weapons attack, the North Koreans overran the advance positions of the company, the mortar observation post, and the heavy machine gun positions. The North Koreans were apparently attempting to control high ground east of Yongp'o in order to provide protection for the main crossing that was to follow.[30] By 0900, however, the 2nd Battalion, supported by the 77th Field Artillery Battalion and air strikes, drove the North Koreans troops back through Yongp'o and dispersed them.[27]

Second Yongp'o attack

In the three days from August 10 to 12 the Naktong River had dropped three feet and was only shoulder-deep at many places due to lack of rains. This made any attempt at crossing the river considerably easier.[30][21]

A more determined North Korean crossing of the Naktong in the vicinity of the blown bridge between Tuksong-dong and Yongp'o began early in the morning on August 14.[27] By 0620, about 500 North Korean soldiers had penetrated as far as Yongp'o. Fifteen minutes later, 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry soldiers engaged the North Koreans at Wich'on-dong, a mile east of the crossing site. At 0800 General Gay ordered 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry to move to the Yongp'o area to support the 2nd Battalion.[31]

North Korean artillery and tank fire from the west side of the river supporting the infantry crossing. A large number of North Korean reinforcements were crossing in barges near the bridge, while under fire from American air strikes and artillery. This attack also stalled, with the deepest North Korean penetration reaching Samuni-dong, 1.5 miles (2.4 km) beyond the blown bridge. There the combined fire of US light weapons, mortars, and artillery drove them back to the river.[24] By 1200, large groups of North Koreans were trying to recross the river to the west side as American artillery continued hammering them, causing heavy casualties.[31]

By nightfall, the 7th Cavalry Regiment had eliminated the North Korean bridgehead at Yongp'o.[31] In the fight, the only major one to take place along the Naktong at a prefabricated crossing site, the 25th and 27th Regiments of the NK 10th Division suffered crippling losses. The 7th Cavalry estimated that of 1,700 North Korean troops who had succeeded in crossing the river, 1,500 were killed. Two days after the battle, H Company reported it had buried 267 enemy dead behind its lines. In front of its position, G Company counted 150 enemy dead. In contrast, G Company suffered only 2 men killed and 3 wounded during the battle.[32] In its first combat mission, the crossing of the Naktong, the 10th Division suffered 2,500 casualties.[27][32]

Hill 303

Almost simultaneously with the NK 10th Division's crossing in the southern part of the 1st Cavalry Division sector at Tuksong-dong and Yongp'o, another was taking place northward above Waegwan near the boundary between the division's sector and the ROK 1st Division's sector. The northernmost unit of the 1st Cavalry Division was G Company of the 5th Cavalry Regiment. It held Hill 303, the furthest position on the Eighth Army's extreme right flank.[32]

For several days UN intelligence sources had reported heavy North Korean concentrations across the Naktong opposite the ROK 1st Division. Early in the morning on August 14, a North Korean regiment crossed the Naktong 6 miles (9.7 km) north of Waegwan into the ROK 1st Division sector through an underwater bridge. Shortly after midnight that night, ROK forces on the high ground just north of the U.S.-ROK Army boundary were attacked by this force. After daylight an air strike partially destroyed the underwater bridge. The North Korean attack spread south and by 1200 North Korean small arms fire fell on G Company, 5th Cavalry Regiment, on Hill 303. Instead of moving east into the mountains as other landings had, this force turned south and headed for Waegwan.[33]

Early in the morning on August 15, G Company men on Hill 303 spotted 50 North Korean infantry supported by two T-34 tanks moving south along the river road at the base of the hill. They also spotted another column moving to their rear which quickly engaged F Company with small arms fire. In order to escape the enemy encirclement, F Company withdrew south, but G Company did not. By 0830, North Koreans had completely surrounded it and a supporting platoon of H Company mortarmen on Hill 303. A relief column, composed of B Company, 5th Cavalry, and a platoon of US tanks tried to reach G Company, but was unable to penetrate the North Korean force that was surrounding Hill 303.[33]

Later that day, B Company and the tanks tried again to retake the hill, now estimated to contain a 700 man battalion. The 61st Field Artillery Battalion and elements of the 82nd Field Artillery Battalion, fired on the hill during the day. During the night, G Company succeeded in escaping from Hill 303.[34] Before dawn on the 17th, troops from both the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 5th Cavalry Regiment, supported by A Company of the 70th Tank Battalion, attacked Hill 303, but heavy North Korean mortar fire stopped them at the edge of Waegwan.[35] During the morning, heavy artillery preparations pounded the North Korean positions on the hill.[34]

At 1400 an air strike came in, with planes bombarded the hill with napalm, bombs, rockets, and machine guns. The strike and artillery preparation, were successful in pushing North Korean forces off the hill. After the strike, the infantry at 1530 attacked up the hill unopposed and secured it by 1630. The combined strength of E and F Companies on top of the hill was about sixty men. The artillery preparations and the air strike killed and wounded an estimated 500 enemy troops on Hill 303, with survivors had fleeing in complete rout after the air strike.[34]

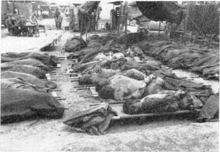

In regaining Hill 303 on August 17, the 5th Cavalry Regiment discovered the bodies of 26 mortarmen of H Company, hands tied in back, with gunshot wounds to the back.[35][36] First knowledge of the event came in the afternoon when scouts brought in a man from Hill 303, Pvt. Roy Manring of the Heavy Mortar Platoon, who had been wounded by automatic weapons fire. Manring had crawled down the hill until he saw scouts of the attacking force.[34] In all about 45 men were shot by the North Koreans in the event, of which only five survived.[37] The total number of men executed around Hill 303 is unclear, as several more men were subsequently discovered in other locations around the hill with evidence of execution.[38] Angered, General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, commander of all UN forces in Korea, broadcast a warning to North Korean leaders they would be held accountable for the atrocity.[39][35] However intercepted documents show the North Korean command was also concerned with the conduct of its troops and issued orders to limit killing of Prisoners of War.[36]

Carpet bombing

In the mountains northeast of Waegwan and Hill 303, the ROK 1st Division continued to suffer North Korean attacks throughout mid-August. North Korean pressure against the ROK division never ceased for long. Under the command of Brigadier General Paik Sun Yup,[40] this division fought an extremely bloody defense of the mountain approaches to Taegu.[41] US planners believed the main North Korean attack would come from west, and so the US command massed its forces to the west of Taegu. The US command mistakenly believed up to 40,000 North Korean troops were near Taegu. This number was above the actual troops numbers for North Korea, which had only 70,000 men along the entire perimeter.[27] American artillery fire from the 1st Cavalry Division sector supported the South Koreans in this area. The division's 13th Regiment still held some positions along the river, while the 11th and 12th Regiments battled the North Koreans in the high mountain masses of Suam-san and Yuhak-san, west and northwest of Tabu-dong and 4 miles (6.4 km) to 6 miles (9.7 km) east of the Naktong River. The North Koreans continued to use the underwater bridge across the Naktong 6 miles (9.7 km) north of Waegwan as their major route for supply and reinforcements. UN forces continued to target this bridge, even scoring a direct hit with a 155mm howitzer, but it was not seriously damaged.[41]

Through the middle of August, North Korean forces relentlessly attacked the sectors occupied by the ROK 13th Regiment and the US 5th Cavalry. This assault, together with increasingly heavy pressure against the main force of the ROK 1st Division in the Tabu-dong area, began to endanger the UN control of Taegu. On August 16, 750 Korean police were stationed on the outskirts of the city to reinforce faltering military lines. Refugees had swollen Taegu's normal population of 300,000 to 700,000.[41] A crisis seemed to be developing among the people on August 18 when several North Korean artillery shells landed in Taegu.[21] The shells, falling near the railroad station, damaged the roundhouse, destroyed one yard engine, killed one Korean civilian, and wounded eight others. The Korean Provincial Government subsequently ordered the evacuation of Taegu, and President Syngman Rhee moved the national leaders to Pusan.[36] Following the ordered evacuation, swarms of panicked Korean refugees began to pour out on the roads leading from the city, threatening to stop all military traffic, but Eighth Army eventually halted the evacuations.[41][21]

On August 14, General MacArthur ordered Lieutenant General George E. Stratemeyer to conduct a carpet bombing of a 27-square-mile (70 km2) rectangular area on the west side of the Naktong River opposite the ROK 1st Division.[27] Intelligence estimates placed the greatest concentrations of enemy troops in this area, some estimates being as high as four enemy divisions and several armored regiments, all of 40,000 men, who were reportedly using the area to stage their attack on Taegu. General Gay, commanding the 1st Cavalry Division, repeatedly requested that the bombing include the area northeast of Waegwan. This request was denied because of fear that bombing there might cause casualties among the 1st Cavalry and ROK 1st Division troops.[42] Stratemeyer did not think his aircraft could successfully carpet bomb an area larger than 3 miles (4.8 km) square but he complied with MacArthur's order anyway.[43]

At 1158, August 16, the first of the 98 B-29 Superfortresses of the 19th, 22nd, 92nd, 98th, and 307th Bomber Groups arrived over the target area from their Far East Air Force bases in Japan and Okinawa. The last planes cleared the target at 1224. The bombers from 10,000 feet dropped approximately 960 tons of 500- and 1,000-pound bombs.[44][42] The attack had required the entirety of the FEAF bombing component, and they had dropped 3,084 500 pounds (230 kg) bombs and 150 1,000 pounds (450 kg) bombs. This comprised the largest Air Force operation since the Battle of Normandy in World War II.[43]

General Walker reported to General MacArthur the next day that the damage done to the North Koreans by the bombing couldn't be evaluated because of smoke and dust, and ground forces couldn't reach it because of North Korean fire.[42] Information obtained later from North Korean prisoners revealed the enemy divisions the Far East Command thought to be still west of the Naktong had already crossed to the east side and were not in the bombed area.[45] No evidence was found that the bombing killed a single North Korean soldier.[43] However, the bombing seems to have destroyed a significant number of North Korean artillery batteries. The UN ground and air commanders opposed future massive carpet bombing attacks against enemy tactical troops unless there was precise information on an enemy concentration and the situation was critical.[45] Instead, they recommended fighter-bombers and dive bombers would better support ground forces.[43] They subsequently canceled a second bombing of an area east of the Naktong scheduled for August 19.[45][44]

Aftermath

The battles around Taegu saw repeated attempts on the part of the North Koreans to attack the city. However, they were repeatedly stopped or slowed by US and South Korean forces. The five North Korean divisions each saw substantial reductions and each eventually collapsed under the strain of mounting losses and lack of supplies. However, some of these divisions' strength were able to disperse into the mountains. Some of these troops would later assemble for different engagements.[45] These final elements of the North Korean army would be finally defeated in the Battle of the Bowling Alley.[21]

Losses among the US 1st Cavalry Division were relatively light. The division suffered a total of about 600 casualties, with around 200 killed in action, including those at Hill 303. American forces in established positions were able to decimate North Korean units crossing the Naktong in the open with artillery.[46] The exact numbers of soldiers captured and executed versus those killed in combat are difficult to determine, owing to conflicting accounts of how many prisoners were actually held on Hill 303.[47] North Korean troops, however, suffered much higher casualties, a higher proportion of their troops were killed in action. This included 2,500 at Yongp'o,[32] 500 at Hill 303,[34] and 700 on Triangulation Hill.[27] This put the total killed at over 3,700, though exact casualties are unknown in the carpet bombing operation because UN scouts were unable to probe the area until much later.[45]

Notes

- ^ Varhola 2000, p. 3

- ^ a b Alexander 2003, p. 52

- ^ Catchpole 2001, p. 15

- ^ a b Varhola 2000, p. 4

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 90

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 105

- ^ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 103

- ^ Appleman 1998, p. 222

- ^ Appleman 1998, p. 221

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 114

- ^ Catchpole 2001, p. 24

- ^ Catchpole 2001, p. 25

- ^ Appleman 1998, p. 247

- ^ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 135

- ^ Appleman 1998, p. 335

- ^ a b c d Appleman 1998, p. 337

- ^ Appleman 1998, p. 253

- ^ Appleman 1998, p. 254

- ^ Leckie 1996, p. 112

- ^ Appleman 1998, p. 336

- ^ a b c d e Catchpole 2001, p. 31

- ^ a b Appleman 1998, p. 338

- ^ a b c d e Appleman 1998, p. 339

- ^ a b Leckie 1996, p. 113

- ^ a b c Alexander 2003, p. 141

- ^ a b c Appleman 1998, p. 340

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Alexander 2003, p. 142

- ^ a b c Appleman 1998, p. 341

- ^ a b Appleman 1998, p. 342

- ^ a b c d Appleman 1998, p. 343

- ^ a b c Appleman 1998, p. 344

- ^ a b c d Appleman 1998, p. 345

- ^ a b Appleman 1998, p. 346

- ^ a b c d e Appleman 1998, p. 347

- ^ a b c Alexander 2003, p. 144

- ^ a b c Fehrenbach 2001, p. 136

- ^ Ecker 2004, p. 16

- ^ Ecker 2004, p. 17

- ^ Leckie 1996, p. 114

- ^ Paik 1992, p. 28

- ^ a b c d Appleman 1998, p. 351

- ^ a b c Appleman 1998, p. 352

- ^ a b c d Alexander 2003, p. 143

- ^ a b Fehrenbach 2001, p. 137

- ^ a b c d e Appleman 1998, p. 353

- ^ Ecker 2004, p. 14

- ^ Ecker 2004, p. 15

References

- Alexander, Bevin (2003), Korea: The First War we Lost, Hippocrene Books, ISBN 978-0781810197

- Appleman, Roy E. (1998), South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu: United States Army in the Korean War, Department of the Army, ISBN 978-0160019180

- Catchpole, Brian (2001), The Korean War, Robinson Publishing, ISBN 978-1841194134

- Ecker, Richard E. (2004), Battles of the Korean War: A Chronology, with Unit-by-Unit United States Causality Figures & Medal of Honor Citations, McFarland & Company, ISBN 978-0786419807

- Fehrenbach, T.R. (2001), This Kind of War: The Classic Korean War History – Fiftieth Anniversary Edition, Potomac Books Inc., ISBN 978-1574883343

- Leckie, Robert (1996). Conflict: The History Of The Korean War, 1950–1953. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0306807169.

- Paik, Sun Yup (1992), From Pusan to Panmunjom, Riverside, NJ: Brassey Inc., ISBN 0028810023

- Varhola, Michael J. (2000), Fire and Ice: The Korean War, 1950–1953, Da Capo Press, ISBN 978-1882810444