Kursk submarine disaster

On 12 August 2000, the Russian Oscar II class submarine Kursk sank in the Barents Sea after an explosion. The investigation showed that a leak of hydrogen peroxide in a torpedo led to explosion of its fuel, causing the submarine to hit the bottom which in turn triggered the detonation of further torpedo warheads about two minutes later. This second explosion was equivalent to about 2-3 tonnes of TNT,[1] large enough to register on seismographs across Northern Europe.[2][3]

Despite a rescue attempt by British and Norwegian teams, which was severely delayed due to the Russians refusing them access, all 118 sailors and officers aboard Kursk died. The next year, a Dutch team recovered the wreckage and all of the bodies, which were buried in Russia.[1]

The explosion

On the morning of 12 August 2000, as part of a naval exercise, Kursk was to fire two dummy torpedoes at Kirov-class battlecruiser Pyotr Velikiy, the flagship of the Northern Fleet. At 11:29 local time (07:29:50 UTC),[1] the 65-76 "Kit" torpedo was loaded into the torpedo tube number 4. High test peroxide, a form of highly concentrated hydrogen peroxide used as oxidiser for the torpedo rocket engine, leaked through bad welds in the tubing into the torpedo and catalytically decomposed on the metals and oxides present there, yielding steam and oxygen. The resulting overpressure ruptured the kerosene fuel tank, resulting in an explosion, causing a weak seismic signature detected hundreds of kilometers away.[4] A similar incident was responsible for the loss of HMS Sidon in 1955.

Recovered remains of the torpedo later allowed pinpointing the first explosion into the middle part of the torpedo. According to the maintenance records, the dummy torpedoes, manufactured in the 1990s, never had their welds checked; it was considered unnecessary as they did not carry a warhead.

The explosive reaction of 1.5 tons of concentrated hydrogen peroxide and 500 kg of kerosene blew off the torpedo tube cover and the internal tube door. (The torpedo tube cover was later found on the seabed and its position relative to the rest of the submarine served as evidence of this version of the event.) The tube door, which should have been capable of resisting such an explosion, was not properly closed; the electrical connectors between the torpedoes and the tube doors were unreliable and often required repeated reclosing of the door before a contact was established, so it is likely that at the moment of explosion the door was not fully closed. The blast entered the front compartment, probably killing all seven men there. The bulkhead should have arrested the blast wave, but it was penetrated by a light air conditioning channel which allowed passage of the blast wave, fire and toxic smoke into the second and perhaps third and fourth compartments, injuring or disorienting the 36 men in the command post located in the second compartment and preventing initiating the emergency blowout and resurfacing the submarine. Additionally, an emergency buoy, designed to release from a submarine automatically when emergency conditions such as rapidly changing pressure or fire are detected and intended to help rescuers locate the stricken vessel, did not deploy. The previous summer, in a Mediterranean mission, fears of the buoy accidentally deploying, and thereby revealing the submarine's position to the U.S. fleet, had led to the buoy being disabled.

Two minutes and fifteen seconds after the initial eruption, a much larger explosion ripped through the submarine. Seismic data from stations across Northern Europe show that the explosion occurred at the same depth as the sea bed, suggesting that the submarine had collided with the sea floor which, combined with rising temperatures due to the initial explosion, had caused other torpedoes to explode. The second explosion was equivalent to 2-3 tons of TNT, or about 5-7 torpedo warheads, and measured 4.2 on the Richter scale. Acoustic data from Pyotr Veliky indicated an explosion of about 7 torpedo warheads in a rapid succession.[1]

The second explosion ripped a 2-square-metre (22 sq ft) hole in the hull of the craft, which was designed to withstand depths of 1,000 metres (3,300 ft), and also ripped open the third and fourth compartments. Water poured into these compartments at 90,000 litres (3,200 cu ft) per second killing all those in the compartments, including five officers from 7th SSGN Division Headquarters. The fifth compartment contained the ship's two nuclear reactors, encased in a further 13 centimetres (5.1 in) of steel. The bulkheads of the fifth compartment withstood the explosion allowing the two reactors, which were resiliently mounted to absorb shock in excess of 50g, to automatically shut down preventing nuclear meltdown or contamination.[1]

Later forensic examination of two of the recovered reactor control room casualties showed extensive skeleton injuries indicating they had sustained shocks of just over 50g during the explosions. This shock would have temporarily disoriented the reactor control operators, and possibly the other sailors.[1]

"It's dark here to write, but I'll try by feel. It seems like there are no chances, 10-20%. Let's hope that at least someone will read this. Here's the list of personnel from the other sections, who are now in the ninth and will attempt to get out. Regards to everybody, no need to be desperate. Kolesnikov."

Captain-lieutenant Dmitri Kolesnikov

Twenty-three men working in the sixth through ninth compartments survived the two blasts. They gathered in the ninth compartment, which contained the secondary escape tunnel (the primary tunnel was in the destroyed second compartment). Captain-lieutenant Dmitri Kolesnikov (one of three officers of that rank surviving) appears to have taken charge, writing down the names of those who were in the ninth compartment. The air pressure in the compartment following the second explosion was still normal surface pressure. Thus it would be possible from a physiological point of view to use the escape hatch to leave the submarine one man at a time, swimming up through 100 metres (330 ft) of Arctic water in a survival suit, to await help floating at the surface.

It is not known if the escape hatch was workable from the inside; opinions differ about how badly it was damaged. However, the men would likely have rejected risking the escape hatch even if it was operable. They may have preferred instead to take their chances waiting for a submarine rescue ship to clamp itself onto the escape hatch. It is not known with certainty how long the remaining men survived in the compartment. As the nuclear reactors had automatically shut down, emergency power soon ran out, plunging the crew into complete blackness and falling temperatures. Kolesnikov wrote two further messages, much less tidily.

There has been much debate over how long the sailors survived. Particularly the Russians say that they would have died very quickly. The Dutch recovery team report a widely believed two to three hour survival time in the least affected stern most compartment.[1] Water leaks into a stationary Oscar-II craft through the propeller shafts, and at 100 metres (330 ft) depth it would have been impossible to plug these. Others point out that the many superoxide chemical cartridges, used to absorb carbon dioxide and release oxygen to enable survival, were found used when the craft was recovered, suggesting that they had survived for several days. Ironically, the cartridges appear to have been the final cause of death; a sailor appears to have accidentally brought a cartridge in contact with oily sea water, causing a chemical reaction and a flash fire. The official investigation into the disaster showed that some men survived the fire by plunging under the water (the fire marks on the walls indicate the water was at waist level in the lower area at this time). However the fire rapidly used up the remaining oxygen in the air, causing death by asphyxiation.

Rescue attempts

Initially the other ships in the exercise, all of which had detected an explosion, did not report it. Each only knew about its own part in the exercise, and ostensibly assumed that the explosion was that of a depth charge, and part of the exercise. It was not until the evening that commanders stated that they became concerned that they had heard nothing from Kursk. Later in the evening, and after repeated attempts to contact Kursk had failed, a search and rescue operation was launched. The rescue ship Rudnitsky carrying two submersible rescue vessels, AS-32 and the Priz (AS-34) reached the disaster area at around 8:40 AM the following morning.

The submarine was found in an upright position, with its nose plowed about 2 meters deep into the clay seabed, at a depth of 108 meters. The periscope was raised, indicating the accident occurred at a low depth. The nose and the bridge showed signs of damage, the conning tower windows were smashed and two missile tube lids were torn off. Fragments of both outer and inner hull were found nearby, including a fragment of Kursk's nose weighing 5 metric tons, indicating a massive explosion in the forward torpedo room.[5][6]

Priz reached Kursk's ninth compartment the day after the accident, but failed to dock with it. Bad weather prevented further attempts on Tuesday and Wednesday. A further attempt on Thursday again made contact but failed to create a vacuum seal required to dock.

The United States offered the use of one of its two Deep Submergence Rescue Vehicles, as did the British government, but all offers were refused by the Russian government. Four days after the accident on 16 August 2000, the Russian government accepted the British and Norwegian governments' assistance and a rescue ship was dispatched from Norway on 17 August and reached the site on 19 August. British and Norwegian deep-sea divers reached the ninth compartment escape hatch on Sunday, 20 August. They were able to determine that the compartment was flooded, and all hope of finding survivors was lost.

Russian government response

"For President Vladimir Putin, the Kursk crisis was not merely a human tragedy, it was a personal PR catastrophe. Twenty-four hours after the submarine's disappearance, as Russian naval officials made bleak calculations about the chances of the 118 men on board, Putin was filmed enjoying himself, shirtsleeves rolled up, hosting a barbecue at his holiday villa on the Black Sea."

Amelia Gentleman[7]

The first fax sent from the Russian Navy to the various Press offices said the submarine had "minor technical difficulties". The government downplayed the incident and then claimed bad weather was making it impossible to rescue the people on board.

On 18 August 2000 Nadezhda Tylik, mother of Kursk submariner Lt. Sergei Tylik, produced an intense emotional outburst in the middle of an in-progress news briefing about Kursk's fate. After attempts to quiet her failed, a nurse injected her with a sedative by force from the back, and she was removed from the room, incapacitated. The event, caught on film, caused further criticism of the government's response to both the disaster, and how the government handled public criticism of said response.

According to Raising Kursk broadcast by the Science Channel:

In June of 2002... the Russian government investigation into the accident officially concluded that a faulty torpedo sank Kursk in the Summer of 2000.

Collision theory

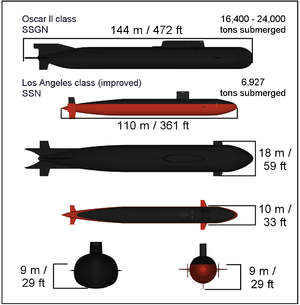

At first, Russian naval sources expressed suspicion that Kursk collided with an American submarine.[8] As is common, the exercise was monitored by two American Los Angeles-class submarines — USS Memphis (SSN-691) and USS Toledo (SSN-769) — and the Royal Navy submarine HMS Splendid; after the disaster the exercise was cancelled and they put in at European ports.[9]

The Guardian wrote in a 2002 review of two books on this topic, Kursk, Russia's Lost Pride and A Time to Die: The Kursk Disaster:[7]

The hopelessly flawed rescue attempt, hampered by badly designed and decrepit equipment, illustrated the fatal decline of Russia's military power. The navy's callous approach to the families of the missing men was reminiscent of an earlier Soviet insensitivity to individual misery. The lies and incompetent cover-up attempts launched by both the navy and the government were resurrected from a pre-Glasnost era. The wildly contradictory conspiracy theories about what caused the catastrophe said more about a naval high command in turmoil, fumbling for a scapegoat, than about the accident itself.

French filmmaker Jean-Michel Carré, in Kursk: a Submarine in Troubled Waters,[10] which aired on 7 January 2005 on French TV channel France 2, alleged that Kursk sank because of a sequence of events triggered by a collision with the US submarine. Carré claimed that Shkval torpedo tests were being observed by two US submarines on duty in the region, USS Toledo and USS Memphis. According to his version, these observations eventually led to occasional collision of USS Toledo with Kursk. Carré theorized that none of the subs were seriously damaged in this incident, but sound of this collision, combined with sounds of loaded torpedo tubes, made captain of USS Memphis to believe that Kursk is preparing an attack on USS Toledo, so he launched an preemptive strike against Kursk with MK-48 torpedo. According to Carré, this attack was successful, and was the cause of powerful explosion within Kursk hull, sinking this submarine, and leaving both Memphis and Toledo slightly damaged. Carré claimed specific damage visible on Kursk hull as the main evidence of his version, including signs of initial collision, and a hole left by torpedo when it entered Kursk hull. He also claimed that a damaged submarine was sighted leaving Kursk incident area, and USS Memphis soon sighted on repairs in Norwegian port.

William S. Cohen (Secretary of Defence of the United States of America, at a press-conference in Tokyo on September 22 2000, declared

Q: Russians are suggesting that one of the possible reasons is a collision with a NATO or American submarine, they are asking to let them, well, have a look at a couple of United States submarines and the answer from the American side is no; so I ask, why not? And what is your own explanation of that particular accident. Thank you.

A: I know that all our ships are operational and could not possibly have been involved in any kind of contact with the Russian submarine. So frankly, there is no need for inspections, since ours are completely operational, there was no contact whatsoever with the Kursk.[8]

Salvage

Most of the submarine's hull, except the bow, was raised from the ocean floor by the Dutch marine salvage companies Smit International and Mammoet in late 2001 and towed back to the Russian Navy's Roslyakovo Shipyard.[1] The front section was cut off because of concerns it could break off and destabilize the lifting, and recovered in 2002.[11] It was cut off using a chain of drums covered with an abrasive, pulled back and forth between two hydraulic anchors dug into the seabed; the cutting took 10 days.[12]

The bodies of its dead crew were removed from the wreck and buried in Russia – three of them were unidentifiable because they were so badly burned. Russian President Vladimir Putin signed a decree awarding the Order of Courage to all the crew and title Hero of the Russian Federation to the submarine's captain, Gennady Lyachin.[13]

The first five fragments to be raised were a piece of a torpedo tube weighing about a ton (to ascertain if the explosion occurred inside or outside), a high-pressure compressed air cylinder weighing about half ton (also to ascertain the nature of the explosion), part of the cylindrical section of the hard frame and part of the left forward spherical partition to determine the intensity and temperature of the fire in the forward compartment, and a fragment of the sonar system dome.[14]

The presence of explosives in the unexploded torpedoes (about 225 kg TNT equivalent each) and especially in the 23 SS-N-19 cruise missiles aboard (about 760 kg each, plus about 7 kg TNT equivalent of the silo ejection charge), together with the risk of radiation release from the reactors, presented a unique set of challenges to the salvage teams.[1]

See also

- List of the Kursk submarine dead

- Nadezhda Tylik

- Major submarine incidents since 2000

- List of sunken nuclear submarines

- Soviet submarine K-129 (1960), sunk in 1968 according to some claims after collision with a US submarine

- Soviet submarine K-278 Komsomolets, sunk in 1989 in Barents Sea after fire and refusal of Western help

- AS-28, Russian mini-submarine trapped underwater in 2005 and saved by the British after initial refusal of help

- National Geographic Seconds From Disaster episodes

- August curse

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Peter Davidson, Huw Jones, John H. Large (October 2003). "The Recovery of the Russian Federation Nuclear Powered Submarine Kursk" (Document). Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers.

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|format=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Seismic Testimony from the Kursk

- ^ Robert B. Herrmann. "Introduction to Earthquakes (EASA-193)" (PDF). Saint Louis University.[dead link]

- ^ Horizon Special: What Sank the Kursk? BBC TWO 9.00pm Wednesday 8th August 2001

- ^ http://www.jamesoberg.com/122000russinfra_rus.html

- ^ http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P1-53681048.html

- ^ a b Review: Kursk and A Time to Die | Special reports, The Guardian, Saturday 24 August 2002

- ^ a b transcript of press conference given by then Secretary of Defence Cohen where he states, in response to Russian requests that they be allowed to inspect the American subs, that neither of them received any damage and continue to be operational. Retrieved 12/13/2008

- ^ "Russia Identifies U.S. Sub". The New York Times. August 31, 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-31.

- ^ Koursk: un sous-marin en eaux troublés. For current screenings see Sundance Channel. IMDb listing for 'Kursk: a Submarine in Troubled Waters'

- ^ http://www.russiajournal.com/node/8634

- ^ http://www.pbs.org/saf/1305/features/ship.htm

- ^ CDI Russia Weekly – Center for Defense Information, Washington, 1 September 2000.Retrieved on 2007-08-07.

- ^ http://www.cdi.org/Russia/211-11.cfm

Further reading

- Robert Moore (2002). A Time To Die: The Kursk Disaster. Bantam Books. ISBN 0-553-81385-4.

- Barany, Zoltan (2004). The Tragedy of the Kursk: Crisis Management in Putin's Russia. Government and Opposition 39.3, 476-503.

- Truscott, Peter (2004): The Kursk Goes Down – pp. 154–182 of Putin's Progress, Pocket Books, London, ISBN 0-7434-9607-8

External links

- The Recovery of the Russian Federation Nuclear Powered Submarine Kursk, Peter Davidson, Huw Jones, John H. Large, Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers - World Maritime Technology Conference, October 2003

- Risks and Hazards in Recovering the Nuclear Powered Submarine Kursk, John H. Large, Royal Institution of Naval Architects, 23–24 June 2005

- Site in Russian

- In depth coverage by the BBC

- Flash Animation of the explosion and the rescue attempts (Turkish)

- Pictures of Kursk in dry dock after explosion

- The Kursk Odyssey, a symphony to the 118 submariners of the Kursk, composed by Didier Euzet

- Sequoya's "Barren the Sea", a folk song about the tragedy — link is sampling of song on CDBaby.com

- English Russia - The Remains of the Kursk Submarine, photographs of the recovered wreck

- BBC World Service, BBC Witness talks to people who experienced the disaster