Sugar glider

| Sugar glider[1] | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | |||||||||||||||||

| Kingdom: | |||||||||||||||||

| Phylum: | |||||||||||||||||

| Class: | |||||||||||||||||

| Infraclass: | |||||||||||||||||

| Order: | |||||||||||||||||

| Family: | |||||||||||||||||

| Genus: | |||||||||||||||||

| Species: | P. breviceps

| ||||||||||||||||

| Binomial name | |||||||||||||||||

| Petaurus breviceps Waterhouse, 1839

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

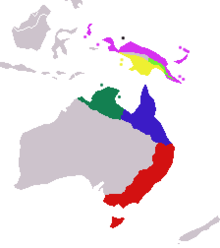

The sugar glider (Petaurus breviceps) is a small gliding marsupial[3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13] native to eastern and northern mainland Australia, New Guinea, and the Bismarck Archipelago, and introduced to Tasmania, Australia.

Habitat

Sugar gliders can be found all throughout Northern and Eastern Australia, along with the surrounding islands of Tasmania, Papua New Guinea, and Indonesia. They can be found in any forest where there is food supply but are commonly found in forests with eucalyptus trees. They are nocturnal, sleeping in their nests during the day and active at night.[14] At night is when they hunt for insects and small vertebrates and feed on the sweet sap of certain species of eucalyptus, acacia and gum trees.[15] The Sugar Glider is named for its preference for sweet foods and its ability to glide through the air, much like a flying squirrel.[15][16]

When suitable habitats are present, sugar gliders can be seen 1 per 1,000 square meters provided that there are tree hollows available for shelter. They live in groups of up to seven adults, plus the current season's young, all sharing a nest and defending their territory, an example of helping at the nest. A dominant adult male will mark his territory and members of the group with saliva and a scent produced by separate glands on the forehead and chest. Intruders who lack the appropriate scent marking are expelled violently.[15]

Appearance and anatomy

A sugar glider has a squirrel-like body with a long partially[17] prehensile tail. The males are larger than the females and their length from nose to tip of tail is about 24 to 30 cm long. A sugar glider has a thick, soft fur coat that is usually a blue-grey; some have been known to be yellow, tan, or albino. A black stripe is seen from its nose to midway of its back. Its belly, throat, and chest is a cream color.[14]

It has five digits on each foot, each having a claw, except for the opposable toe on the hindfeet. Also on the hindfeet the second and third digits are partially syndactylous (fused) together to form a grooming comb.[18] Its most striking feature is the patagium, or membrane, that extends from the fifth finger to the first toe. When legs are stretched out this membrane allows it to glide distances 50–150 meters. This gliding is regulated by changing the curvature of the membrane or moving the legs and tail.[19]

Another feature are the scent glands, located on the frontal (forehead), sternal (chest), and paracloacal (cloaca). These are used for marking purposes mainly for the males. The frontal is easily seen on adult males as a bald spot. The male also has a bifurcated (two shafts) penis. The female has a marsupium (pouch) in the middle of her abdomen to carry offspring.[18]

Torpor

During the cold season, drought, or rainy nights a sugar glider’s activity is reduced. This is usually seen due to torpor. In the winter season or drought there is a decrease in food supply, which is a challenge for this marsupial because of the energy cost for the maintenance of its metabolism,[20] locomotion, and thermoregulation. With energetic constraints the sugar glider will enter into daily torpor for 2–23 hours while in rest phase.[21] However, before entering torpor a sugar glider will reduce activity and body temperature normality in order to lower energy expenditure and avoid torpor.[20][22]

Torpor, which is seen as an emergency measure, allows the animal to save energy by allowing its body temperature to fall to a minimum of 10.4°C.[21] to 19.6°C [23] When the food is scarce, as in winter, heat production is lowered in order to reduce energy expenditure.[24] With low energy and heat production it is important for the sugar glider to peak its body mass, by fat content, in autumn(May/June) [25] in order to survive the following cold season. In the wild, sugar gliders enter into daily torpor more often than sugar gliders in captivity.[22][23]

Diet and nutrition

Like many exotic animals, the Sugar Glider can suffer from calcium deficiencies if it isn't fed an adequate diet.[26] Calcium to phosphorus ratios should be 2:1 to prevent hypocalcemia sometimes known as hind leg paralysis (HLP).[27]

In the wild, gliders live off gum and sap (typically from the eucalyptus), acacia trees, nectar and pollen, manna and honeydew and a wide variety of insects and arachnids. A captive glider's diet should be 50% pelleted feed marketed for Sugar Gliders, and 50% insects (gut-loaded and dusted with mineral supplements) or insectivorous diets, per rehabilitator's guidelines in their native Australia.

Some of the more recognized diets are BML, HPW, and Priscilla's.[clarification needed]

Dry food/pellets should never be given as it can cause abrasions in the mouth and throat of the glider and cause intestinal blockage[citation needed] .

Breeding

The age of sexual maturity in sugar gliders varies slightly between the males and females. The males reach maturity between 4–12 months old while females reach maturity between 8–12 months. In the wild, sugar gliders breed once to twice a year depending on the climate and habitat conditions while they can breed multiple times a year in captivity as a result of consistent living conditions and proper diet.[18]

A sugar glider female has one (19%) to two (81%) joeys a litter. The gestation period is 15 to 17 days, after which the baby sugar glider (0.2g) will crawl into a mother’s pouch for further development. It is virtually unnoticeable the female is pregnant until after the joey has climbed into her pouch and begins to grow, forming bumps in her pouch. Once in the pouch, the joey will attach itself to its mother’s nipple where it will stay for about 60 to 70 days. The joey gradually spills out of the pouch until it falls out completely. The mother can get pregnant while her joey/s are still ip (in pouch), and hold the pregnancy until the pouch is available. Their eyes will remain closed for another 12–14 days and they are virtually furless at first. During this time they will begin to mature by starting to grow fur and increasing gradually in size. It is about two months for the offspring to be completely weaned off of the mother, and at four months they are on their own.[18]

emily is awesome

Conservation status

Unlike many native Australian animals, particularly smaller ones, the Sugar Glider is not endangered.[28] Despite the massive loss of natural habitat in Australia over the last 200 years, it is adaptable and capable of living in surprisingly small patches of remnant bush, particularly if it does not have to cross large expanses of clear-felled land to reach them. Several close relatives, however, are endangered, particularly Leadbeater's Possum and the Mahogany Glider. The Sugar Glider is protected by law in Australia, where it is illegal to keep them without a permit,[29] or to capture or sell them without a license (which is usually only issued for research).

As pets

Outside Australia, the Sugar Glider is a popular domestic pet, but is one of the most commonly traded wild animals in the dangerous, illegal, and traumatizing exotic pet trade, where animals are plucked directly from their natural habitats. [30]

Taxonomy

There are seven subspecies of P. breviceps:

- P. b. breviceps (Waterhouse, 1839)

- P. b. longicaudatus (Longman, 1924)

- P. b. ariel (Gould, 1842)

- P. b. flavidus (Tate & Archbold, 1935)

- P. b. papuanus (Thomas, 1888)

- P. b. tafa (Tate & Archbold, 1935)

- P. b. biacensis (Ulmer, 1940)

<<<----you are gay

References

- ^ Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 55. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Template:IUCN2008 Database entry includes justification for why this species is of least concern

- ^ Sugar Glider — Unique Australian Animals

- ^ Gliding Possums — Environment, New South Wales Government

- ^ Tasmanian Governmetn

- ^ Cronin, Leonard — "Key Guide to Australian Mammals", published by Reed Books Pty. Ltd., Sydney, 1991 ISBN 0 7301 03552

- ^ van der Beld, John — "Nature of Australia — A portrait of the island continent", co-published by William Collins Pty. Ltd. and ABC Enterprises for the Australian Boadcasting Corporation, Sydney, 1988 (revised edition 1992), ISBN 0 7333 0241 6

- ^ Russell, Rupert — "Spotlight on Possums", published by University of Queensland Press, St. Lucia, Queensland, 1980, ISBN 0 7022 14787

- ^ Troughton, Ellis — "Furred Animals of Australia", published by Angus and Robertson (Publishers) Pty. Ltd, Sydney, in 1941 (revised edition 1973), ISBN 0 207 12256 3

- ^ Morcombe, Michael & Irene — "Mammals of Australia", published by Australian Universities Press Pty. Ltd, Sydney, 1974, ISBN 0 7249 00179

- ^ Ride, W. D. L. — "A Guide to the Native Mammals of Australia", published by Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1970, ISBN 19 550252 3

- ^ Serventy, Vincent — "Wildlife of Australia", published by Thomas Nelson (Australia) Ltd., Melbourne, 1968 (revised edition 1977), ISBN 0 17 005168 4

- ^ Serventy, Vincent (editor) — "Australia's Wildlife Heritage", published by Paul Hamlyn Pty. Ltd., Sydney, 1975

- ^ a b "Sugar Glider - Petaurus breviceps". Angelfire.com. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- ^ a b c "Sugar Glider — Department of Primary Industries and Water, Tasmania". Dpiw.tas.gov.au. 28 October 2009. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- ^ "Sugar Glider — Australian Fauna". Australianfauna.com. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- ^ http://www.webvet.com/main/article/id/1815

- ^ a b c d "A guide to medicine and surgery in sugar gliders". Hilltopanimalhospital.com. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- ^ "Sugar Glider Fun Facts". Drsfostersmith.com. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- ^ a b "Metabolic Rate and Body Temperature Reduction During Hibernation and Daily Torpor - Annual Review of Physiology, 66(1):239 - Abstract". Arjournals.annualreviews.org. 15 October 2003. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- ^ a b "Journal Article". SpringerLink. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- ^ a b "Journal Article". SpringerLink. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- ^ a b "Journal Article". SpringerLink. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- ^ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11765973

- ^ "Australian weather and the seasons - Australia's Culture Portal". Cultureandrecreation.gov.au. 17 March 2008. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- ^ "Microsoft Word - Care of Hamsters.doc" (PDF). Retrieved 22 June 2010. [dead link]

- ^ A. Lennox. "Emergency and Critical Care Procedures in Sugar Gliders (Petaurus breviceps), African Hedgehogs (Atelerix albiventris), and Prairie Dogs (Cynomys spp)". Veterinary Clinics of North America: Exotic Animal Practice. 10 (2): 533–555.

- ^ Gliders - Monash University[dead link]

- ^ "Fauna Permits — Government of South Australia". Environment.sa.gov.au. 3 July 1972. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- ^ "Insider the Exotic Pet Trade: Fatal Attractions". discovery.com. Retrieved 22 October 2010.

External links

- Gliders in the Spotlight — Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland

- Sugar Glider — Australian Fauna

- Information about the Sugar Glider from Tasmanian Parks

- IUCN Red List least concern species

- Use dmy dates from October 2010

- Possums

- Pet mammals

- Mammals of New Guinea

- Mammals of Indonesia

- Pollinators

- Mammals of Western Australia

- Mammals of South Australia

- Mammals of the Northern Territory

- Mammals of Queensland

- Mammals of New South Wales

- Mammals of Victoria (Australia)