Sentence spacing

Sentence spacing is the horizontal space between sentences in typeset text. It is a matter of typographical convention.[1] Since the introduction of movable-type printing in Europe, various sentence spacing conventions have been used in languages with a Latin-derived alphabet.[2] These include a normal word space (as between the words in a sentence), a single enlarged space, and two full spaces. Although modern digital fonts can automatically adjust a single word space to create visually pleasing and consistent spacing following terminal punctuation,[3] most debate is about whether to strike a keyboard's spacebar once or twice between sentences.[4]

Until the 20th century, publishing houses and printers in many countries used single, but enlarged, spaces between sentences.[5] There were exceptions to this traditional spacing method—printers in some countries preferred single spacing.[6] This was French spacing—a term synonymous with single space sentence spacing until the late 20th century.[7] Double spacing,[8] or placing two spaces between sentences (sometimes referred to as English spacing), came into widespread use with the introduction of the typewriter in the late 19th century.[9] It was felt that with the monospaced font used by a typewriter, "a single word space ... was not wide enough to create a sufficient space between sentences"[10] and that extra space might help signal the end of a sentence.[11] This caused a widespread change in practice. From the late 19th century, printers were told to ignore their typesetting manuals in favor of typewriter spacing; Monotype and Linotype operators used double sentence spacing[11] and this was widely taught in typing classes.[12]

With the introduction of proportional fonts in computers, double sentence spacing became obsolete.[13] These proportional fonts now assign appropriate horizontal space to each character (including punctuation marks), and can modify kerning values to adjust spaces following terminal punctuation, so there is less need to manually increase spacing between sentences.[10] From around 1950, single sentence spacing became standard in books, magazines and newspapers.[14] Regardless, many still believe that double spaces are correct. The debate continues,[4] notably on the World Wide Web—as many people use search engines to try to find what is correct.[15] Many people prefer double sentence spacing for informal use because that was how they were taught to type.[16] There is a debate on which convention is more legible, and the few recent direct studies have produced inconclusive results.[17]

Most modern literature on typography says that double spacing is wrong,[18] but some non-typographical sources indicate that it could be used on a typewriter or with a monospaced font.[19] The majority of style guides opt for a single space after terminal punctuation for final and published work, with a few permitting double spacing in draft manuscripts and for specific circumstances based on personal preference.[20] Grammar and design guides, including Web design guides, provide similar guidance.[21]

History

Traditional typesetting

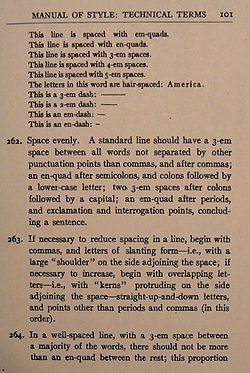

Early printing systems were limited to inflexible word spacing. Improvements that allowed variable spacing soon appeared.[22] Early American, English, and other European typesetters' style guides (also known as printers' rules) specified spacing standards that were all essentially identical from the 18th century onwards. These guides—e.g., Jacobi in the UK (1890)[23] and MacKellar, Harpel, and De Vinne (1866–1901) in the U.S.[24]—indicated that sentences should be em-spaced, and that words should be 1/3 or 1/2 em-spaced (illustration right). Only a single type block was typically used, which resulted in the appearance of about a double word space between sentences.[25] For most countries, this remained the standard for published work until the 20th century.[26] Yet, even in this period, there were publishing houses (notably in France) that used a standard word space between sentences—a technique called French spacing (illustration below).

Mechanical type and the advent of the typewriter

Mechanical type systems introduced near the end of the 19th century, such as the Linotype and Monotype machines, allowed variable sentence spacing.[27] However, with the advent of the typewriter and its widespread usage beginning in the late 19th century, the average text composer had only two possibilities—to strike the space bar once or twice between sentences. The typewriter's mechanical limitations did not allow variable spacing. This caused a fundamental change in sentence spacing methods. Typists in some English-speaking countries learned to insert two spaces between sentences to approximate the exaggerated sentence spacing used in traditional printing,[28] a practice that continued throughout the 20th century.[9] This became known as English spacing, and marked a divergence from French typists, who continued to use French spacing.[29]

Transition to single spacing

Professional printers moved from double to single sentence spacing in the 20th century. Magazines, newspapers, and books began to adopt the single space convention in the United States in the 1940s and in the United Kingdom in the 1950s.[30] Typists did not transition to single spacing simultaneously. The average writer still relied on the typewriter to create text—with its inherent mechanical spacing limitations.

Technological advances began affecting sentence spacing methods. In 1941, IBM introduced the Executive, a typewriter capable of proportional spacing[31]—which had been used in professional typesetting for hundreds of years. This innovation broke the hold that the monospaced font had on the typewriter—reducing the severity of its mechanical limitations.[32] "By the 1960s, electric phototyping systems" ignored runs of white space in text,[33] a feature that reappeared on the World Wide Web, as HTML ignores additional spacing.[34] Computers offered additional sentence spacing tools for the average writer,[35] and the double spacing convention, "as a standard operating procedure ... went out with the IBM Selectric".[36] By the late 20th century, literature on the written word had begun to adjust its guidance on sentence spacing.

Modern literature

Typography

Early positions on typography (the "arrangement and appearance of text")[37] supported traditional spacing techniques in English publications. In 1954, Geoffrey Dowding's book, Finer Points in the Spacing and Arrangement of Type, underscored the widespread shift from a single enlarged em space to a standard word space between sentences.[38]

With the advent of the computer age, typographers began deprecating double spacing, even in monospaced text. In 1989, Desktop Publishing by Design stated that "typesetting requires only one space after periods, question marks, exclamation points, and colons", and identified single sentence spacing as a typographic convention.[39] Stop Stealing Sheep & Find Out How Type Works (1993) and Designing with Type: The Essential Guide to Typography (2006) both indicate that uniform spacing should be used between words, including between sentences.[40]

More recent works on typography weigh in strongly. Ilene Strizver, founder of the Type Studio, says, "Forget about tolerating differences of opinion: typographically speaking, typing two spaces before the start of a new sentence is absolutely, unequivocally wrong."[16] The Complete Manual on Typography (2003) states that "The typewriter tradition of separating sentences with two word spaces after a period has no place in typesetting" and the single space is "standard typographic practice".[41] The Elements of Typographic Style (2004) advocates a single space between sentences, noting that "your typing as well as your typesetting will benefit from unlearning this quaint [double spacing] Victorian habit."[9]

David Jury's book, About Face: Reviving the Rules of Typography (2004)—published in Switzerland—clarifies the contemporary typographic position on sentence spacing:

Word spaces, preceding or following punctuation, should be optically adjusted to appear to be of the same value as a standard word space. If a standard word space is inserted after a full point or a comma, then, optically, this produces a space of up to 50% wider than that of other word spaces within a line of type. This is because these punctuation marks carry space above them, which, when added to the adjacent standard word spaces, combines to create a visually larger space. Some argue that the "additional" space after a comma and full point serves as a "pause signal" for the reader. But this is unnecessary (and visually disruptive) since the pause signal is provided by the punctuation mark itself.[42]

Style and language guides

Style guides

Early style guides used a single em space in their text—traditional spacing (illustration right).[43] By the 1980s, the United Kingdom's Hart's Rules (1983)[44] and the United States' Chicago Manual of Style (1969) had shifted to single sentence spacing.[45] Other style guides followed suit in the 1990s.[46] Soon after the turn of the century, the majority of style guides indicated that only one word space was proper between sentences.[47]

Modern style guides provide standards and guidance for the written language. These works are important to writers since "virtually all professional editors work closely with one of them in editing a manuscript for publication."[48] Late editions of comprehensive style guides, such as the Oxford Style Manual (2003)[49] in the United Kingdom and the Chicago Manual of Style (2010)[50] in the United States, provide standards for a wide variety of writing and design topics, including sentence spacing.[51] The majority of style guides prescribe the use of a single space after terminal punctuation in final written works and publications.[52] A few style guides allow double sentence spacing for draft work. Web design guides do not usually provide guidance on this topic, as "HTML refuses to recognize double spaces altogether".[53] These works themselves follow the current publication standard of single sentence spacing.[54]

The European Union's Interinstitutional Style Guide (2008) indicates that single sentence spacing is to be used in all European Union publications—encompassing 23 languages.[55] For the English language, the European Commission's English Style Guide (2010) states that sentences are always single-spaced.[56] The Style Manual: For Authors, Editors and Printers (2007), first published in 1966 by the Commonwealth Government Printing Office of Australia, stipulates that only one space is used after "sentence-closing punctuation", and that "Programs for word processing and desktop publishing offer more sophisticated, variable spacing, so this practice of double spacing is now avoided because it can create distracting gaps on a page."[57]

National languages not covered by an authoritative language academy typically have multiple style guides—only some of which may discuss sentence spacing. This is the case in the United Kingdom. The Oxford Style Manual (2003) and the Modern Humanities Research Association's MHRA Style Guide (2002), state that only single spacing should be used.[58] In Canada, both the English and French language sections of the Canadian Style, A Guide to Writing and Editing (1997), prescribe single sentence spacing.[59] In the United States, many style guides—such as the Chicago Manual of Style (2003)—allow only single sentence spacing.[60] The most important style guide in Italy, Il Nuovo Manuale di Stile (2009),[61] does not address sentence spacing, but the Guida di Stile Italiano (2010), the official guide for Microsoft translation, tells users to use single sentence spacing "instead of the double spacing used in the United States".[62]

Language guides

Some languages, such as French and Spanish, have academies that set language rules. Their publications typically address orthography and grammar as opposed to matters of typography. Style guides are less relevant for such languages, as their academies set prescriptive rules. For example, the Académie française publishes the Dictionnaire de l'Académie française for French speakers worldwide.[63] The 1992 edition does not provide guidance on sentence spacing, but is single-sentence-spaced throughout—consistent with historical French spacing. The Spanish language is similar. The most important body within the Association of Spanish Language Academies, the Real Academia Española, publishes the Diccionario de la Lengua Española, which is viewed as prescriptive for the Spanish language worldwide.[64] The 2001 edition does not provide sentence spacing guidance, but is itself single sentence spaced. The German language manual Empfehlungen des Rats für Deutsche Rechtschreibung ("Recommendations of the Council for German Orthography") (2006) does not address sentence spacing.[65] The manual itself uses one space after terminal punctuation. Additionally, the Duden, the German language dictionary most commonly used in Germany,[66] indicates that double sentence spacing is an error.[67]

Grammar guides

A few reference grammars address sentence spacing, as increased spacing between words is punctuation in itself.[68] Most do not. Grammar guides typically cover terminal punctuation and the proper construction of sentences—but not the spacing between sentences.[69] Moreover, many modern grammar guides are designed for quick reference[70] and refer users to comprehensive style guides for additional matters of writing style.[71] For example, the Pocket Idiot's Guide to Grammar and Punctuation (2005) points users to style guides such as the MLA Style Manual for consistency in formatting work and for all other "editorial concerns".[72] The Grammar Bible (2004) states that "The modern system of English punctuation is by no means simple. A book that covers all the bases would need to be of considerable breadth and weight and anyone interested in such a resource is advised to consult the Chicago Manual of Style."[73]

Digital age

Mignon Fogarty, "Grammar Girl", points out that in the past, typewriting used two spaces—in deference to its monospaced font limitations—but "Now that most writing is done on computers it is no longer necessary to type two spaces after a period at the end of a sentence."[51] She answers the question of "How many spaces?" as follows: "On a typewriter, use two. On a computer, use one."[74] This position highlights the late 20th-century transition from the typewriter to the computer, and its effect on sentence spacing.

Today, computers and digital fonts allow sentence spacing variations not possible with the typewriter. Proportional fonts are widely available to average computer users. Computer-based tools such as proportional fonts, kerning, computer-based word processors, and software such as TeX allow users to arrange text in a manner previously only available to professional typesetters.[75] These tools are also available on the World Wide Web, even though single spacing is the convention because of the characteristics of HTML.[53] Yet, even in the digital age, many school students are still taught to strike the space bar twice between sentences when using computers, contributing to 21st-century sentence spacing misconceptions.[16]

Controversy

James Felici, author of the Complete Manual of Typography, says that the topic of sentence spacing is "the debate that refuses to die ... In all my years of writing about type, it's still the question I hear most often, and a search of the web will find threads galore on the subject".[4] This subject is still widely debated today because many typists were taught to use double sentence spacing in school.[76] As a result, there is a common misconception that double sentence spacing is "correct", even given modern technology and proportional fonts.[15] This is similar to other obsolete typewriter conventions, practiced in deference to its "severe technical limitations", that are still used by writers. These include the use of prime marks (or "dumb quotes") for quotation marks, underlining words in place of italics, and using hyphens to approximate en and em dashes.[77]

Many people are opposed to single sentence spacing for various reasons. Some state that the habit of double spacing is too deeply ingrained to change.[19] Others claim that additional space between sentences makes text "look better" or easier to read.[78] Proponents of double sentence spacing also state that some publishers may still require double spaced manuscript submissions from authors. A key example noted is the screenwriting industry's monospaced "standard" for screenplay manuscripts, Courier, 12-point font, although some works on screenwriting indicate that proportional fonts may be used.[79] Some reliable sources state simply that writers should follow their particular style guide, but proponents of double spacing caution that publisher's guidance takes precedence, including those that ask for double sentence spaced manuscripts.[80]

In opposition to these ideas, many experts state that double sentence spacing was only relevant when faced with the limitations of the typewriter, and is now obsolete for most uses, especially given the capabilities of modern computers and digital fonts.[81] While typewriter users had only two choices (to strike the space bar once or twice), modern proportional fonts allow users to manually adjust sentence spacing to thousandths of an inch for visually pleasing typesetting.[82] It is also acceptable even for monospaced fonts to be single spaced today.[83] Another consideration is that as terminal punctuation marks the end of a sentence, and additional spacing is itself punctuation,[9] additional spacing is redundant.

There is concern that, because the double space typewriter convention is still being taught widely in school,[16] students will later be forced to relearn how to type.[84] Most style guides indicate that single sentence spacing is proper for final or published work today,[85] and "most publishers" require manuscripts to be submitted as they will appear in publication—single sentence spaced.[86] Writing sources typically recommend that prospective authors remove extra spaces before submitting manuscripts,[87] although publishers will use software to remove the spaces before final publication.[88] Finally, some experts state that, while double spacing sentences in unpublished papers and informal use (such as e-mail) might be fine,[89] double sentence spacing in desktop-published (DTP) works will make the final result look "unprofessional" and "foolish".[90]

Effects on readability and legibility

Claims abound regarding the legibility and readability of the single and double sentence spacing methods—by proponents on both sides. Supporters of single spacing assert that familiarity with the current standard in books, magazines, and the Web enhances readability, that double spacing looks strange in text using proportional fonts, and that the "rivers" and "holes" caused by double spacing impair readability.[91] Proponents of double sentence spacing state that the extra space between sentences enhances readability by providing breaks between sentences and makes text appear more legible.[92]

However, typographic opinions are typically anecdotal with no basis in evidence.[93] "Opinions are not always safe guides to legibility of print",[94] and when direct studies are conducted, anecdotal opinions—even those of experts—can turn out to be false. [95] Text that seems legible (visually pleasing at first glance), may be shown to actually impair reading effectiveness when subjected to scientific study.[96]

Studies

Few studies have been conducted on sentence spacing. Direct studies include those by Loh, Branch, Shewanown, and Ali (2002), Clinton, Branch, Holschuh, and Shewanown (2003) and Ni, Branch and Chen (2004) with inconclusive results favoring single or double spacing.[97] The 2002 study tested participants' reading speed for single and double sentence spaced passages of on-screen text. The authors stated that "the 'double space group' consistently took longer time to finish than the 'single space' group", but concluded that "there was not enough evidence to suggest that a significant difference exists".[98] The 2003 and 2004 studies analyzed on-screen single, double, and triple spacing. In both cases, the authors stated that there was insufficient evidence to draw a conclusion.[99] Ni, Branch, Chen, and Clinton conducted a similar study in 2009 using identical spacing variables. The authors concluded that the "results provided insufficient evidence that time and comprehension differ significantly among different conditions of spacing between sentences".[100]

Related studies

There are other studies that could be relevant to sentence spacing,[101] such as the familiarity of typographic conventions on readability. Some studies indicate that "tradition" can increase the readability of text,[102] and that reading is disrupted when conventional printing arrangements are disrupted or violated.[103] The modern standard for the Web and published books, magazines, and newspapers is single sentence spacing.[19]

A widespread observation is that increased sentence spacing creates "rivers"[104] or "holes"[105] within text, making it visually unattractive, distracting, and difficult to locate the end of sentences. [106] Comprehensive works on typography describe the negative effect on readability caused by inconsistent spacing,[107] supported in a 1981 study which found that "comprehension was significantly less accurate with the river condition."[108] Another 1981 study on cathode ray tube (CRT) displays concluded that "more densely packed text is read more efficiently ... than is more loosely packed text."[109] This conclusion is supported in other works as well.[107]

Canadian typographer Geoffrey Dowding provided an explanation for this phenomenon:

A carefully composed text page appears as an orderly series of strips of black separated by horizontal channels of white space. Conversely, in a slovenly setting the tendency is for the page to appear as a grey and muddled pattern of isolated spats, this effect being caused by the over-widely separated words. The normal, easy, left-to-right movement of the eye is slowed down simply because of this separation; further, the short letters and serifs are unable to discharge an important function—that of keeping the eye on "the line". The eye also tends to be confused by a feeling of vertical emphasis, that is, an up & down movement, induced by the relative isolation of the words & consequent insistence of the ascending and descending letters. This movement is further emphasized by those "rivers" of white which are the inseparable & ugly accompaniment of all carelessly set text matter.[110]

Some studies suggest that readability might be improved by segmenting sentences into shorter word phrases. Mid-20th-century research on this topic resulted in inconclusive findings.[111] A 1980 study split sentences into phrases of between one to five words with additional spacing between segments. The study concluded that there was no significant difference in efficacy but that a wider study was needed.[112] Numerous other similar studies in 1951–1991 resulted in disparate and inconclusive findings.[113]

Finally, various studies have been conducted on the readability of proportional vs. monospaced fonts. These studies typically did not decrease sentence spacing when using proportional fonts or did not specify whether sentence spacing was changed.[114]

See also

Notes

- ^ University of Chicago Press 2003, Chicago Manual of Style. p. 243; Einsohn 2006. p. 113; Shushan and Wright 1989. p. 34.

- ^ Languages with Sanscrit, Cyrillic, cuneiform, hieroglyphics, Chinese, and Japanese characters, among others, are not covered in the scope of this article. Handwriting is also not covered.

- ^ Felici 2003. p. 80; Fogarty 2008. p. 85; Straus 2009. p. 52.

- ^ a b c Felici 2009.

- ^ MacKellar 1885. p. 78; University of Chicago Press 1911 Chicago Manual of Style. p. 101.

- ^ Felici 2009

- ^ In the 1990s, some print and Web sources began referring to double sentence spacing as "French spacing", leading to some ambiguity with the term. See for example, Eckersley et al. 1994. p. 46, and Haley 2006.

- ^ Felici 2003. p. 80; Bringhurst 2004. p. 28; Walsh 2004. p. 3; Williams 2003. 13.

- ^ a b c d Bringhurst 2004. p. 28.

- ^ a b Felici 2003. p. 80.

- ^ a b Jury 2009. p. 58.

- ^ Bringhurst 2004. p. 28; Williams 2003. pp. 13–14; Strizver 2010.

- ^ Felici 2003. p. 80; Fogarty 2008. p. 85; Jury 2009. p. 56; Strizver 2010; Walsh 2004. p. 3; Williams 2003. pp. 13–14.

- ^ Williams 2003. pp. 13–14. This refers to professionally published works, as it is possible for individual authors to publish works through desktop publishing systems. Williams states, "I guarantee this: never in your life have you read professionally set text printed since 1942 that used two spaces after each period." See also, Felici 2003. p. 81; Strizver 2010; Weiderkehr 2009; Williams 1995. p. 4.

- ^ a b Rosendorf 2010.

- ^ a b c d Strizver 2010.

- ^ Lloyd and Hallahan 2009. "During times when many disciplines that recommend the APA's Publication Manual [6th ed., 2009] are advocating evidence-based decisions, it's noteworthy, we think, that these discussions of the rationale for using two spaces at the end of sentences (and after colons) do not appear to be based on scientific examination of the hypothesis that two spaces makes manuscripts more readable."

- ^ Bringhurst 2004. p. 28; Felici 2003. p. 80; Strizver 2010; Spiekermann and Ginger 1993. p. 123; Dowding 1995. 29.

- ^ a b c Williams 2003. p. 13.

- ^ American Sociological Association 1997. pp. i, 11; University of Chicago Press 2003, Chicago Manual of Style. p. 243; Garner, Newman and Jackson 2006. p. 83; Sabin 2005. pp. 5–6.

- ^ Fogarty 2008. p. 85; Shushan and Wright 1989. p. 34; Walsh 2004. p. 3.

- ^ DeVinne 1901. p. 142.

- ^ Jacobi 1890.

- ^ MacKellar 1885; Harpel 1870. p. 19; DeVinne 1901. p. 78.

- ^ Chicago University Press 1911. p. 101. Variable-spaced text (professionally typeset) is unlikely to result in a sentence space exactly twice the size of a word space (which can be seen with a typewriter or monospaced font). Variables such as whether a 1/3 or 1/2 word space is used, and whether the text is justified or unjustified, will vary the difference between a sentence space and word space.

- ^ Felici 2009. Felici illustrates that there are other examples of standard single word spaces used for sentence spacing in this period.

- ^ Dodd 2006. p. 73; Mergenthaler Linotype 1940.

- ^ Jury 2009. 58. This primarily refers to the United States and Great Britain.

- ^ Imprimerie nationale 1993.

- ^ Felici 2009; University of Chicago Press 2009; Williams 2003. p. 14.

- ^ Wershler-Henry 2005. p. 254.

- ^ Wershler-Henry 2005. pp. 254–255.

- ^ Felici 2009.

- ^ Lupton 2004. p. 165. HTML normally ignores all additional horizontal spacing between text.

- ^ Jury 2009. p. 57.

- ^ Walsh 2004. p. 3.

- ^ American Medical Association 2007. p. 917.

- ^ Dowding 1995.

- ^ Shushan and Wright 1989. p. 34.

- ^ Craig 2006. p. 90; Spiekermann and Ginger 1993, p. 123.

- ^ Felici 2003. pp. 80–81.

- ^ Jury 2004. p. 92.

- ^ De Vinne 1901; University of Chicago Press 1911; Hart 1893.

- ^ Hart 1983.

- ^ University of Chicago Press 1969 Chicago Manual of Style. p. 438. (1st edition published in 1906.) The 1969 edition of the Chicago Manual of Style is single sentence spaced and stated that "Spacing between words will vary slightly from line to line, but all word spacing in a single line should be the same" (438).

- ^ American Sociological Association.

- ^ Rhodes 1999; Leonard 2009.

- ^ Lutz and Stevenson 2005. p. viii.

- ^ Ritter 2003. The 2003 edition of the Oxford Style Manual combined the Oxford Guide to Style (first published as Horace Hart's Rules for Compositors and Readers at the University Press, Oxford in 1893) and the Oxford Dictionary for Writers and Editors (first published as the Authors' and Printers' Dictionary in 1905) Preface.

- ^ University of Chicago Press Chicago Manual of Style 2010.

- ^ a b Fogarty 2008. p. 85.

- ^ Rhodes 1999; Leonard 2009.

- ^ a b Lupton 2004. p. 165.

- ^ Strunk and White 1999. (1st edition published in 1918.); Council of Science Editors 2006. (1st edition published in 1960.); American Medical Association 2007. (1st edition published in 1962.)

- ^ Publications Office of the European Union 2008. (1st edition published in 1997.) This manual is "obligatory" for all those in the EU who are involved in preparing EU documents and works [1]. It is intended to encompass 23 languages within the European Union [2].

- ^ European Commission Directorate-General for Translation. p. 22. (1st edition published in 1982.) "Note in particular that ... stops (. ? ! : ;) are always followed by only a single (not a double) space."

- ^ John Wiley & Sons Australia 2007. p. 153. The Commonwealth is an organization of 54 English-speaking states worldwide.

- ^ Ritter 2003 Oxford Style Manual, 2003. p. 51. (First published as the MHRA Style Book in 1971.) "In text, use only a single word space after all sentence punctuation."; Modern Humanities Research Association 2002. p. 6.

- ^ Dundurn Press 1997. p. 113. (1st edition published in 1987.); Public Works and Government Services of Canada 2010. p. 293. "17.07 French Typographical Rules—Punctuation: Adopt the following rules for spacing with punctuation marks. [table] Mark: Period, before: none, after: 1 space."

- ^ University of Chicago Press 2003 Chicago Manual of Style. p. 61. "2.12 A single character space, not two spaces, should be left after periods at the ends of sentences (both in manuscript and in final, published form)." p. 243. "6.11 In typeset matter, one space, not two (in other words, a regular word space), follows any mark of punctuation that ends a sentence, whether a period, a colon, a question mark, an exclamation point, or closing quotation marks." p. 243. "6.13 A period marks the end of a declarative or an imperative sentence. It is followed by a single space."

- ^ Lesina 2009. (1st edition published in 1986.) "Prefazione: Il manuala intende fornire una serie di indicazioni utili per la stesura di testi di carattere non inventive, quali per esempio manuali, saggi, monografie, relazioni professionali, tesi di laurea, articoli per riviste, ecc." (Trans: "[S]tyle manual for academic papers, monographs, professional correspondence, theses, articles, etc.) Preface; Carrada 2010. "Roberto Lesina, Il nuovo manuale di stile, Zanichelli 2009. L'unico vero manuale di stile italiano, di cui nessun redattore può fare a meno". (Trans: "The only real Italian style guide, a must-have for any writer".) The 2009 edition is itself single sentence spaced.

- ^ Microsoft 2010. p. 4.1.8. "Assicurarsi ad esempio che tra la fine e l'inizio di due periodi separati da un punto venga usato un unico spazio prima della frase successiva, invece dei due spazi del testo americano ... A differenza di altre lingue, non va inserito nessuno spazio prima dei segni di punteggiatura." (Trans."Make sure that between two sentences separated by a period a single space is used before the second sentence, instead of the double spacing used in the United States ... Contrary to other languages, no space is to be added before punctuation marks.")

- ^ Académie française 1992. French is spoken in 57 countries and territories throughout the world, including Europe, North America, and Francophone Africa. Qu'est-ce que la Francophonie?

- ^ Real Academia Española 2001. p. 2.

- ^ Council for German Orthography 2010.

- ^ Bibliographisches Institut AG 2010.

- ^ Bibliographisches Institut AG 2010. The Duden was the primary orthography and language guide in Germany until the German orthography reform of 1996 created a multinational council for German orthography for German-speaking countries—composed of experts from Germany, Austria, Liechtenstein and Switzerland. The current version of the Duden reflects the most recent opinions of this council.

- ^ Bringhurst 2004. p. 30. Bringhurst implies that additional spacing after terminal punctuation is redundant when combined with a period, question mark, or exclamation point. Other sources indicate that the function of terminal punctuation is to mark the end of a sentence and additional measures to perform the same measures are unnecessary.

- ^ Baugh 2005. p. 200; Cutts 2009. p. 79; Garner 2009. p. 935; Lester 2005; Loberger 2009. p. 158; Stevenson 2005. p. 123; Straus 2009. p. 52; Strumpf. p. 408; Taggart 2009.

- ^ Baugh 2005. p. 200; Hopper 2004; Stevenson 2005. p. 123.

- ^ Fogarty 2008. p. 85; Loberger 2009. p. 158.

- ^ Stevenson 2005. pp. xvi, 123.

- ^ Strumpf 2004. p. 408.

- ^ Fogarty 2009. p. 78. Other grammar guides recommend one space for computer users. Some indicate that monospaced text could be double spaced in view of the typewriter tradition. See Lutz and Stevenson 2005. pp. 200–202. The Writing Digest Grammar Desk Reference (2005) indicates that "On typed pages, two blank spaces traditionally follow a sentence-ending period", but that "Many editors ... now prefer only a single space" after terminal punctuation. The Blue Book of Grammar and Punctuation (2009) echoes this opinion in that computer users should "use only one space", and with "some typewriters and word processors, [users should] follow ending punctuation with two spaces when using fixed-pitch fonts". See also Straus 2009. p. 52.

- ^ Felici 2003. 80; Fogarty 2008. p. 85; Fogarty 2009. p. 78; Fondiller and Nerone 2007. 93; Garner, Newman and Jackson 2006. 83; Modern Language Association 2009 77; Straus 2009. p. 52.

- ^ Bringhurst 2004. p. 28; Smith 2009; Strizver 2010; Williams 2003. p. 13.

- ^ Jury 2009. p. 56; Lupton 2004. pp. 164–166; Rosendorf 2009. p. 42; Strizver 2010. pp. 197–201; Williams 2003. pp. 15–16, 21–24, 31–32.

- ^ Williams 95. p. 1; Sabin 2005. pp. 5–6.

- ^ Trotter 1998. p. 112. Trottier refers to Courier as the industry "standard". Some authors provide dissenting opinions. Russin and Downs state that other fonts are also acceptable for screenplay manuscripts today. Russin and Downs 2003. p. 17. The authors state that "Courier 12-point is preferred, although New York, Bookman, and Times will do". Moira Anderson Allen suggests that publishers are more interested in readable fonts as opposed to maintaining a monospaced font standard.Allen 2001.

- ^ Loberger 2009. p. 158; Stevenson 2005. p. 123; Sambuchino 2009. p. 10.

- ^ Bringhurst 2004. p. 28; Felici 2003. p. 80; Fogarty 2008. p. 85; Jury 2009. p. 56; Shushan and Wright 1989. p. 34; Smith 2009; Straus 2009. p. 52; Strizver 2010; Walsh 2004. p. 3; Williams 2003. p. 13.

- ^ Felici 2003. p. 80; Fogarty 2008. p. 85; Straus 2009. p. 52.

- ^ Sabin 2005. p. 5; Trottier 2005. pp. 118–121. The Screenwriter's Bible uses single sentence spaced 12-point Courier text in its formatting examples for screenwriters.

- ^ Lloyd and Hallahan 2009.

- ^ Rhodes 1999; Leonard 2009.

- ^ University of Chicago Press 2010. p. 60; Lutz 2005. p. 200; Modern Language Association 2009. pp. 77–78.

- ^ Modern Humanities Research Association 2002. p. 6; Sabin 2005. p. 5; Felici 2003. p. 81.

- ^ Fogarty 2008. p. 85;Weiderkehr 2009; University of Chicago Press 2010. p. 83. Fogarty also stated in Grammar Girl's Quick and Dirty Tips for Better Writing that numerous page designers have contacted her stating that two spaces between sentences require them to edit the pages to remove the extra spaces. The 16th edition of the Chicago Manual of Style instructs editors to remove extra spaces between sentences when preparing a manuscript for publication.

- ^ University of Chicago Press Chicago Manual of Style Online 2007; Williams 2003. p. 13.

- ^ Williams 1995; Williams 2003. p. 13.

- ^ Williams 2003. 13; Smith 2009.

- ^ Jury 2004. 92; Williams 1995.

- ^ Wheildon 1995. p. 13.

- ^ Tinker 1963. p. 50.

- ^ Tinker 1963. pp. 88, 108, 127, 128, 153; Wheildon 1995. pp. 8, 35.

- ^ Tinker 1963. pp. 50, 108, 128. A useful example is the Helvetica font, an ubiquitous font that is considered extremely legible (visually pleasing in the construction and viewing of its characters), but has been found to impair reading effectiveness (readability). See Squire 2006. p. 36.

- ^ Leonard et al. 2009.

- ^ Loh et al., 2002. p. 4.

- ^ Clinton 2003. The study did not find "statistically significant differences, between reading time of single and double spaces passages".

- ^ Ni et al. 2009. pp. 383, 387, 390. This study "explored the effects of spacing after the period on on-screen reading tasks through two dependent variables, reading time and reading comprehension".

- ^ Rhodes 1999.

- ^ Tinker 1963. p. 124.

- ^ Haber and Haber 1981. pp. 147–148, 152.

- ^ Dowding 1995. p. 29; Felici 2003. p. 80; Fogarty 2008. p. 85; Schriver 1997. 270; Smith 2009; Squire 2006. p. 65.

- ^ Garner 2006. p. 83; John Wiley & Sons 2007. p. 153; Jury 2009. p. 58; Jury 2004. p. 92; Rollo 1993. p. 4; Williams 2003. p. 13.

- ^ Craig and Scala 2006. p. 64; The Design and Publishing Center, cited in Rhodes 1999; Garzia, R.P, and R. London. Vision and Reading. (1995). Mosby Publishing, St Louis. Cited in Scales 2002. p. 4. Other studies show that "irregular and uneven spacing" disrupts the text and may slow the reader; John Wiley & Sons Australia 2007. p. 270. The context of the "irregular and uneven spacing" is concerning justified text.

- ^ a b Dowding 1995. p. 5; Jury 2004. p. 92.; Ryder 1979. p. 23.

- ^ Campbell, Marchetti, and Mewhort 1981. cited in Schriver 1997. p. 270.

- ^ Kolers, Duchinsky, and Ferguson 1981.

- ^ Dowding 1995. pp. 5–6, 29.

- ^ Tinker 1963; North and Jenkins 1951. p. 68., cited in Tinker 1963. p. 125.

- ^ Hartley 1980. pp. 62, 64–65, 70, 74–75. The sentences averaged 25.4 words each. Hartley does not identify which font type and sentence spacing method was used in his study. The author notes other studies, three of which found a positive correlation between segmenting parts of sentences and reading efficacy, three that noted no significance, and one that indicated a negative effect. The additional studies noted were: "Coleman and Kim, 1961; Epstein, 1967; and Murray, 1976 (with positive results); those of Nahinsky, 1956; Hartley and Burnhill, 1971; and Burnhill et al., 1975 (with non-significant results); and that of Klare et al., 1957 (a negative result)" (64).

- ^ Bever 1991. pp. 78–80, 83–87. The text materials used in the research inserted various characters, such as pound signs in the spaces between phrases, visually interrupting the "river" effect. This study also analyzed various spacing techniques. It did not vary spacing between sentences or identify font type used, and concluded that "isolating major phrases within extra spaces facilitates reading." The article lists similar studies. The research in 14 studies in 1951–1986 correlated with the findings in the article, and six studies in 1957–1984 were inconclusive.

- ^ Payne 1967. pp. 125–136; Black and Watts 1993.

References

Further reading

- "Writing Tips: Soft and Hard Spaces". Writer's Block. NIVA Inc. 2009. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) See also "Spacing 2"

External links

- "Double-spacing After Periods". Typophile. Punchcut. 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Rhodes, John S. (13 May 1999). "One Versus Two Spaces After a Period". WebWord.com. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help)