Griffin

The griffin, griffon, or gryphon (Greek: γρύφων, grýphōn, or γρύπων, grýpōn, early form γρύψ, grýps; Template:Lang-lat) is a legendary creature with the body of a lion and the head and wings of an eagle. As the lion was traditionally considered the king of the beasts and the eagle was the king of the birds, the griffin was thought to be an especially powerful and majestic creature. Griffins are known for guarding treasure and priceless possessions.[1] Adrienne Mayor, a classical folklorist, proposes that the griffin was an ancient misconception derived from the fossilized remains of the Protoceratops found in gold mines in the Altai mountains of Scythia, in present day southeastern Kazakhstan.[2] In antiquity it was a symbol of divine power and a guardian of the divine.[3] Some have suggested that the word griffin is cognate with Cherub.[4]

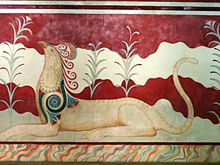

Most statues have bird-like talons, although in some older illustrations griffins have a lion's forelimbs; they generally have a lion's hindquarters. Its eagle's head is conventionally given prominent ears; these are sometimes described as the lion's ears, but are often elongated (more like a horse's), and are sometimes feathered. The earliest depiction of griffins are the 15th century BC frescoes in the Throne Room of the Bronze Age Palace of Knossos, as restored by Sir Arthur Evans. It continued being a favored decorative theme in Archaic and Classical Greek art. In Central Asia the griffin appears about a thousand years after Bronze Age Crete, in the 5th-4th century BC, probably originating from the Achaemenid Persian Empire. The Achaemenids considered the griffin "a protector from evil, witchcraft and secret slander".[5] The modern generalist calls it the lion-griffin, as for example, Robin Lane Fox, in Alexander the Great, 1973:31 and notes p. 506, who remarks a lion-griffin attacking a stag in a pebble mosaic Dartmouth College expedition at Pella, perhaps as an emblem of the kingdom of Macedon or a personal one of Alexander's successor Antipater.

Infrequently, a griffin is portrayed without wings, or a wingless eagle-headed lion is identified as a griffin; in 15th-century and later heraldry such a beast may be called an alce or a keythong. In heraldry, a griffin always has forelegs like an eagle's; the beast with forelimbs like a lion's forelegs was distinguished by perhaps only one English herald of later heraldry as the opinicus.

Medieval lore

Griffins not only mated for life, but also, if either partner died, then the other would continue throughout the rest of its life alone, never to search for a new mate. A Hippogriff is a legendary creature, supposedly the offspring of a griffin and a mare.

According to Stephen Friar, a griffin radford's claw was believed to have medicinal properties and one of its feathers could restore sight to the blind.[1] Goblets fashioned from griffin claws (actually antelope horns) and griffin eggs (actually ostrich eggs) were highly prized in medieval European courts.[6]

When it emerged as a major seafaring power in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, griffins commenced to be depicted as part of the Republic of Genoa's coat of arms, rearing at the sides of the shield bearing the Cross of St. George.

By the 12th century the appearance of the griffin was substantially fixed: "All its bodily members are like a lion's, but its wings and mask are like an eagle's."[7] It is not yet clear if its forelimbs are those of an eagle or of a lion. Although the description implies the latter, the accompanying illustration is ambiguous. It was left to the heralds to clarify that.

Heraldic significance

In heraldry, the griffin's amalgamation of lion and eagle gains in courage and boldness, and it is always drawn to powerful fierce monsters. It is used to denote strength and military courage and leadership. Griffins are portrayed with a lion's body, an eagle's head, long ears, and an eagle's claws, to indicate that one must combine intelligence and strength.[8]

In British heraldry, a male griffin is shown with wings, its body covered in tufts of formidable spikes. The male griffin is more usually shown, as in the Bevan family crest.[9] Also they can be seen as sacred animals to the Greek god Apollo [citation needed]

In architecture

In architectural decoration the griffin is usually represented as a four-footed beast with wings and the head of an eagle with horns, or with the head and beak of an eagle.[citation needed]

Gryphon statues mark the entrance to the City of London.

In literature

- For fictional characters named Griffin, see Griffin (surname)

Flavius Philostratus mentioned them in The Life of Apollonius of Tyana:

As to the gold which the griffins dig up, there are rocks which are spotted with drops of gold as with sparks, which this creature can quarry because of the strength of its beak. “For these animals do exist in India” he said, “and are held in veneration as being sacred to the Sun ; and the Indian artists, when they represent the Sun, yoke four of them abreast to draw the images ; and in size and strength they resemble lions, but having this advantage over them that they have wings, they will attack them, and they get the better of elephants and of dragons. But they have no great power of flying, not more than have birds of short flight; for they are not winged as is proper with birds, but the palms of their feet are webbed with red membranes, such that they are able to revolve them, and make a flight and fight in the air; and the tiger alone is beyond their powers of attack, because in swiftness it rivals the winds.[10]

And the griffins of the Indians and the ants of the Ethiopians, though they are dissimilar in form, yet, from what we hear, play similar parts; for in each country they are, according to the tales of poets, the guardians of gold, and devoted to the gold reefs of the two countries.[11]

Griffins are used widely in Persian poetry; Rumi is one such poet who writes in reference to griffins.[12]

In Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy, Beatrice meets Dante in Earthly Paradise after his journey through Hell and Purgatory with Virgil have concluded. Beatrice takes off into the Heavens to begin Dante's journey through paradise on a flying Griffin that moves as fast as lightning. Sir John Mandeville wrote about them in his 14th century book of travels:

In that country be many griffins, more plenty than in any other country. Some men say that they have the body upward as an eagle and beneath as a lion; and truly they say sooth, that they be of that shape. But one griffin hath the body more great and is more strong than eight lions, of such lions as be on this half, and more great and stronger than an hundred eagles such as we have amongst us. For one griffin there will bear, flying to his nest, a great horse, if he may find him at the point, or two oxen yoked together as they go at the plough. For he hath his talons so long and so large and great upon his feet, as though they were horns of great oxen or of bugles or of kine, so that men make cups of them to drink of. And of their ribs and of the pens of their wings, men make bows, full strong, to shoot with arrows and quarrels.[13]

John Milton, in Paradise Lost II, refers to the legend of the griffin in describing Satan:

As when a Gryfon through the Wilderness

With winged course ore Hill or moarie Dale,

Pursues the ARIMASPIAN, who by stelth

Had from his wakeful custody purloind

The guarded Gold [...]

Modern uses

The griffin is the symbol of the Philadelphia Museum of Art; bronze castings of them perch on each corner of the museum's roof, protecting its collection.[14][15] Similarly, prior to the mid-1990s a griffin formed part of the logo of Midland Bank (now HSBC). The griffin has appeared in over 500 film in the U.S. alone.

The griffin is the logo of United Paper Mills, Vauxhall Motors, and of Scania and its former group partners SAAB-Aircraft and Saab Automobile. The latest fighter produced by the SAAB-Aircraft company bears the name of "Gripen" (Griffin), but as a result of public competition. General Atomics has used the term "Griffin Eye" for its intelligence surveillance platform based on a Hawker Beechcraft King Air 35ER civilian aircraft [16]

Pakistan Air Force has her No. 9 squadron named as Griffins. The squadron was formed in 1943 and is currently equipped with F-16 fighter aircraft.

School emblems and mascots

The Gryphon is the official mascot of the University of Guelph (Guelph, Ontario, Canada). The Guelph Gryphons are the athletic teams that represent the University, and are members of the Canadian Interuniversity Sport.

In 1933, Canisius College in Buffalo, New York selected the griffin as the mascot for its athletic teams and newspaper, in part in reference to the Jesuit-educated La Salle's ship which had sailed nearby 244 years earlier. In announcing the naming of the mascot, the college's president, the Very Rev. Rudolph J. Eichhorn,S.J., said:

In adopting the name Griffin for our newspaper and athletic teams, we feel we are using a synonym for Canisian. He should display at all times loyalty and courage in the face of any odds; he should be superior, in the good sense, to the commonplace; and like the griffins who kept watch over the material treasures of gold and precious stones, so should he guard the intellectual, spiritual and moral treasure which have been given into his keep.[17]

The official seal of Purdue University was adopted during the University's centennial in 1969. The seal, approved by the Board of Trustees, was designed by Prof. Al Gowan, formerly at Purdue. It replaced an unofficial one that had been in use for 73 years.

In medieval heraldry, a griffin symbolized strength, and Abby P. Lytle used it in her 1895 design for a Purdue seal. When Professor Gowan redesigned the seal, he retained the griffin symbol to continue identification with the older, unofficial seal. The three-part shield indicates three stated aims of the University: education, research, and service, replacing the words Science, Technology, and Agriculture on the earlier version.[18]

The griffin is the mascot of The Cambridge School of Weston, a coeducational private day and boarding school located in Weston, Massachusetts. The mascot is also the name of the school publication: "The Gryphon."

The griffin is the mascot of Greenhills School in Ann Arbor, Michigan, a independent Middle and High School.

The griffin is the mascot of Rocky Mount High School located in Rocky Mount, North Carolina. During the era of segregation, Rocky Mount High School was an all-white school while African Americans attended Booker T. Washington High School. In 1969, the two schools merged when segregation ended. During that time, the mascot of Rocky Mount High School was the blackbird, and the lion was the mascot of Booker T. Washington. In an attempt to create a new mascot for the newly merged school and at the same time maintaining the history of the two schools, the griffin, or "gryphon" as it is then spelled, mostly became the obvious choice.

The griffin is part of the coat of arms of Raffles Institution, the oldest school in Singapore. Combined with the strength of the double-headed eagle, it represents power, strength, supremacy, dignity and majesty for the school.[19]

The griffin is the mascot of Missouri Western State University in Saint Joseph, Missouri. It was chosen in 1918 as the mascot of Saint Joseph Junior College, the institution which later became Missouri Western State University. The griffin was selected because it was considered a guardian of riches, and education is viewed as a precious treasure. Similarly, originating from founder Simeon Reed's family coat of arms, the griffin became the unofficial mascot of Reed College, in Portland, Oregon as the "protector of "man and beasts" and as the enemy of ignorance".[20]

Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley, Massachusetts uses four animals and colors to represent the four class years. One of these is the green griffin, representing one of the odd graduating years. It was selected as one of the four class animals in 1909.[21]

The College of William and Mary in Virginia changed its mascot to the griffin in April 2010.[22][23] The griffin was chosen because it is the combination of the British lion and the American eagle.

The griffin is the mascot of Seton Hill University located in Greensburg, PA. The university changed its mascot from "Spirits" to "Griffins" in 2002 after transitioning from a women's college to a coeducational university. Seton Hill competes as an NCAA Division II school as a member of the West Virginia Intercollegiate Athletic Conference (WVIAC).

After many years of not having an official mascot, Sarah Lawrence College has dubbed all of its teams "The Gryphons."

The "Golden Griffin" is the official mascot of St. John Vianney High School in Kirkwood, Missouri.

The Griffin is the mascot of Wichita Northeast Magnet High School in Wichita, KS. It was chosen for the school because it combines both the science and art magnet areas, which are both concentrations that students may choose when attending the school.

At the University of Toronto intramural teams from University College are known as the UC Gryphons.[24]

In natural history

Some large species of Old World vultures are called gryphons, including the Griffon Vulture (Gyps fulvus). The scientific name for the Andean Condor is Vultur gryphus, Latin for "griffin-vulture".

Notes and references

- ^ a b Friar, Stephen (1987). A New Dictionary of Heraldry. London: Alphabooks/A & C Black. p. 173. ISBN 0906670446.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help) - ^ Adrienne Mayor, Archeology Magazine, November–December 1994, pp 53-59; Mayor, The First Fossil Hunters, 2000.

- ^ von Volborth, Carl-Alexander (1981). Heraldry: Customs, Rules and Styles. Poole: New Orchard Editions. pp. 44–45. ISBN 185079037X.

- ^ William H. C. Propp,Exodus 19-40, volume 2A of The Anchor Bible, New York: Doubleday, 2006, ISBN 0-385-24693-5, Notes to Exodus 15:18, page 386, referencing: Julius Wellhausen, Prolegomena to the History of Israel, Edinburgh: Black, 1885, page 304. Also see: Robert S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, volume 1, Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2010 ISBN 978-90-04-17420-7, page 289, entry for γρυπος, "From the archaeological perspective, origin in Asia Minor (and the Near East: Elam) is very probable."

- ^ Neva, Elena. "Central Asian Jewelry and their Symbols in Ancient Time" Kunstpedia; citing Pugachenkova, G. (1959) "Grifon v drevnem iskusstve central’noi Azii." Sovetskya Arheologia, 2 pp.70, 83

- ^ Bedingfeld, Henry (1993). Heraldry. Wigston: Magna Books. pp. 80–81. ISBN 1854224336.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ White, T. H. (1992 (1954)). The Book of Beasts: Being a Translation From a Latin Bestiary of the Twelfth Century. Stroud: Alan Sutton. pp. 22–24. ISBN 075090206X.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Stefan Oliver, Introduction to Heraldry. David & Charles, 2002. P. 44.

- ^ For a recent use of a griffin in heraldry see the Baty Griffin and millstone

- ^ Flavius Philostratus, The Life of Apollonius of Tyana, translated by F. C. Conybeare, volume I, book III.XLVIII., 1921, p. 333.

- ^ Flavius Philostratus, The Life of Apollonius of Tyana, translated by F. C. Conybeare, volume II, book VI.I., 1921, p. 5.

- ^ The Essential Rumi, translated from Persian by Coleman Barks, p 257

- ^ The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, Chapter XXIX, Macmillan and Co. edition, 1900.

- ^ Philadelphia Museum of Art - Giving : Giving to the Museum : Specialty License Plates

- ^ Philadelphia Museum of Art :: Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States :: Glass Steel and Stone

- ^ [1]

- ^ http://canisiusarchives.cdmhost.com/cdm4/document.php?CISOROOT=/p124801coll0&CISOPTR=6&REC=1 The Griffin, vol. 1, issue 1, Sept. 29, 1933

- ^ http://www.purdue.edu/facts/pages/traditions.html

- ^ Raffles Institution Handbook

- ^ Facilities and Grounds Reed College

- ^ Mount Holyoke College - Traditions: Class Colors and Symbols

- ^ Deadspin.com

- ^ W&M welcomes newest member of the Tribe April 8, 2010

- ^ http://ucsoftball.wordpress.com/

Further reading

- Bisi, Anna Maria, Il grifone: Storia di un motivo iconografico nell'antico Oriente mediterraneo (Rome: Università) 1965.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wood, James, ed. (1907). The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

External links

- The Gryphon Pages, a repository of griffin lore and information

- The Medieval Bestiary: Griffin

- Dave's Mythical Creatures and Places: Griffin