Navajo

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| United States (Navajo Nation, Arizona, New Mexico, Utah) | |

| Languages | |

| Navajo, English | |

| Religion | |

| Traditional, Christianity, Native American Church (NAC), other | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Apachean (Southern Athabascan) peoples |

The Navajo (also spelled Navaho; in Navajo: Diné, meaning "the people," or Naabeehó) (or Dineh in a common anglicization of the Navajo-language term) of the Southwestern United States are the second largest Native American tribe of the United States of America. In the 2000 U.S. census, 298,197 people claimed to be fully or partly of Navajo ancestry.[1] The Navajo Nation constitutes an independent governmental body which manages the Navajo Indian reservation in the Four Corners area of the United States. The Navajo language is spoken throughout the region, although most Navajo speak English as well.

History

Early history

Until they came into contact with the Spanish and Pueblos, the Navajo were hunters and gatherers. They adopted farming techniques and crops from the Pueblo people, growing mainly corn, beans, and squash. As a result of Spanish influence, they began herding sheep and goats, depending on them for food and trade.[2] They spun and wove sheared wool into blankets and clothing which could be used for personal use or trading.[3] They also depended on their flocks of sheep for meat.[4] Their lives depended on sheep so much that, to the Navajo, sheep were a kind of currency and the size of the herd was a mark of social status.[5]

The Navajo/Diné speak dialects of the language family referred to as Athabaskan.[6] The Navajo and Apache are believed to have migrated from northwestern Canada and eastern Alaska, where the majority of Athabaskan speakers reside.[7] The Dene First Nations, who live near from Tadoule Lake in Manitoba to the Great Slave Lake in Alberta, also speak Athabaskan languages.[8] Despite the time elapsed, these people reportedly can still understand the language of their distant cousins the Navajo.[9] Archaeological and historical evidence suggests that the Athabaskan ancestors of the Navajo and Apache entered the Southwest by 1400 CE.[10] Navajo oral traditions are said to retain references of this migration.[11]

Navajo oral history also seems to indicate a long relationship with Pueblo people[12] and a willingness to adapt foreign ideas into their own culture. Trade between the long-established Pueblo peoples and the Athabaskans was important to both groups. The Spanish records say by the mid-16th century, the Pueblos exchanged maize and woven cotton goods for bison meat, hides and material for stone tools from Athabaskans who either traveled to them or lived around them. In the 18th century, the Spanish reported that the Navajo had large numbers of livestock and large areas of crops. The Navajo probably adapted many Pueblo ideas into their own different culture.

The Spanish first used the term Apachu de Nabajo in the 1620s to refer to the people in the Chama Valley region east of the San Juan River and northwest of present-day Santa Fe, New Mexico. By the 1640s, they were using "Navajo" for these indigenous people. The Spanish recorded in 1670s that they lived in a region called Dinetah, about sixty miles (100 km) west of the Rio Chama valley region. In the 1780s, the Spanish sent military expeditions against the Navajo in the southwest and west of that area, in the Mount Taylor and Chuska Mountain regions of New Mexico.

In the last 1,000 years, Navajos have had a history of expanding their range and refining their self-identity and their significance to other groups. This probably resulted from a cultural combination of endemic warfare (raids) and commerce with the Pueblo, Apache, Ute, Comanche and Spanish peoples, set in the changing natural environment of the Southwest.[citation needed]

Conflict with Europeans

The Spanish started to establish a military force along the Rio Grande in the 17th century to the east of Dinetah (the Navajo homeland). Spanish records indicate that Apachean groups allied themselves with the Pueblos over the next 21 years, successfully pushing the Spaniards out of this area following the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. Raiding and trading were part of traditional Apache and Navajo culture, and these activities increased following the introduction of the horse by the Spaniards, which increased the efficiency and frequency of raiding expeditions. The Spanish established a series of forts that protected new Spanish settlements and also separated the Pueblos from the Apaches.

In the 18th century, Spanish-Navajo relations were improved for 50 years, the constant incursions of Yutas and Comanches against Navajos.[clarification needed] The Spaniards—and later, Mexicans—recorded what are called punitive expeditions[by whom?] among the Navajo that also took livestock and human captives. In 1772, King Charles III of Spain issued a reglamento for the northern frontier of New Mexico, declaring that the main objective of any military operation against the Indians was to get peace and that the death penalty would apply to anyone who killed an Indian prisoner. Non-neutral Navajo tribes or groups in turn raided settlements far away in a similar manner.[clarification needed] This pattern continued, with the Athabaskan groups apparently growing to be more formidable foes through the 1840s until the United States Army arrived in the area.

New Mexico Territory

Officially, the Navajos first came in contact with forces of the United States of America in 1846, when General Stephen W. Kearny invaded Santa Fe with 1,600 men during the Mexican American War. In 1846, following an invitation from a small party of American soldiers under the command of Captain John Reid who journeyed deep into Navajo country and contacted him, Narbona and other Navajos negotiated a treaty of peace with Colonel Alexander Doniphan on November 21, 1846, at Bear Springs, Ojo del Oso (later the site of Fort Wingate). The treaty was not honored by young Navajo raiders who continued to steal stock from New Mexican villages and herders.[13] New Mexicans, on their part, together with Utes, continued to raid Navajo country stealing stock and taking women and children for sale as slaves.

In 1849, the military governor of New Mexico, Colonel John Macrae Washington – accompanied by John S. Calhoun, Indian agent – led a force of 400 into Navajo country, penetrating Canyon de Chelly, and there signed a treaty with two Navajo leaders who held themselves out as "Head Chief" and "Second Chief" acknowledging the jurisdiction of the United States and allowing forts and trading posts in Navajo land. The United States, on its part, promised "such donations [and] such other liberal and humane measures, as [it] may deem meet and proper". Narbona had been killed along the way in an unhappy accident.[14]

In the next 10 years, the U.S. established forts in traditional Navajo territory. Military records state this was to protect citizens and Navajo from each other. However, the old Spanish/Mexican-Navajo pattern of raids and expeditions against one another continued. New Mexican (citizen and militia) raids increased rapidly in 1860–61, earning it the Navajo name Naahondzood, "the fearing time."

In 1861 Brigadier-General James H. Carleton, the new commander of the Federal District of New Mexico, initiated a series of military actions against the Navajo. Colonel Kit Carson was ordered by Carleton to conduct an expedition into Navajo land and receive their surrender on July 20, 1863.[clarification needed] A few Navajo surrendered. Carson was joined by a large group of New Mexican militia volunteer citizens and these forces moved through Navajo land, killing Navajos and destroying any Navajo crops, livestock or dwellings they came across. Facing starvation, Navajo groups started to surrender in what is known as The Long Walk.

Long Walk

Starting in the spring of 1864, around 9,000 Navajo men, women and children were forced on The Long Walk of over 300 miles (480 km) to Fort Sumner, New Mexico. This was the largest reservation (called Bosque Redondo)[citation needed] attempted by the U.S. government. It was a failure for a combination of reasons. It was designed to supply water, wood, supplies, and livestock for 4,000–5,000 people; it had one kind of crop failure after another; other tribes and civilians were able to raid the Navajo; and a small group of Mescalero Apaches had been moved there. In 1868, a treaty was negotiated that allowed the surviving Navajos to return to a reservation that was a portion of their former nation.

Conflict on the reservation

The United States military continued to maintain the forts. Some Navajo were employed by the military as “Indian Scouts” through 1895. A Navajo Tribal Police operated between 1872 and 1875 and was used by the Navajo themselves to stop raiders from their tribe; it was created by Manuelito.

By treaty, the Navajo people were allowed to leave the reservation with permission to trade. Raiding by the Navajo essentially stopped, because they were able to increase the size of their livestock and crops, and not have to risk losing them to others. However, while the initial reservation increased from 3.5 million acres (14,000 km²) to the 16 million acres (65,000 km²) of today, economic conflicts with the non-Navajo continued. Civilians and companies raided resources that had been assigned to the Navajo. Livestock grazing leases, land for railroads, and mining permits are a few examples of actions taken by agencies of the U.S. government who could and did do such things on a regular basis.

Regional newspapers have many accounts of Navajo and non-Navajo conflicts in this period. These conflicts were often embellished, for political purposes, by regional politicians. In some of these accounts, every Navajo was just about to leave the reservation and pillage the countryside or worse. While it is probably true that some Navajo strayed, it is equally true that some white citizens clearly strayed from the laws of the land themselves. In their reports, the U.S. Military never seemed to be that alarmed about a Navajo uprising, and they clearly did not want the Navajo stirred up by their neighbors.

In 1883, Lt. Parker, accompanied by 10 enlisted men and two scouts, went up to the San Juan River to separate Navajos and citizens who had encroached on Navajo land. In the same year, Lt. Lockett, with the aid of 42 enlisted soldiers, was joined by Lt. Holomon at Navajo Springs. Evidently, citizens of the surname(s) Houck and/or Owens had murdered a Navajo chief's son and 100 armed Navajos were consequently looking for them.

In 1887, citizens Palmer, Lockhart, and King fabricated a charge of horse stealing and attacked at random a home on the reservation. Two Navajo men and all three whites died, but a woman and a child survived. Capt Kerr (with two Navajo scouts) examined the ground and then met with several hundred Navajo at Houcks Tank. Rancher Bennett, whose horse was allegedly stolen, pointed out to Kerr that his horses were stolen by the three whites to catch a horse thief. In the same year, Lt. Scott went to the San Juan River with two scouts and 21 enlisted men. The Navajo believed Lt. Scott was there to drive off the whites who had settled on the reservation and had fenced off the river from the Navajo. Scott told them to wait, and found evidence of many non-Navajo ranches. However, only three were active, and the owners refusee to leave, wanting payment for their improvements. Scott ejected them.

In 1890, a local rancher refused to pay the Navajo a fine of livestock. The Navajos tried to collect it, and whites in southern Colorado and Utah claimed that 9,000 of the Navajo people were on a warpath. A small military detachment out of Fort Wingate restored white citizens to order.

In 1913, an Indian agent ordered a Navajo and his three wives to come in, and then arrested them for having a plural marriage. A small group of Navajo used force to free the women and retreated to Beautiful Mountain with 30 or 40 sympathizers. They refused to surrender to the agent, and local law enforcement and military refused the agent's request for an armed engagement. General Scott arrived, and with the help of Henry Chee Dodge, defused the situation.

In the 1930s, the United States government took action against the Navajo that was as culturally and economically devastating as the Long Walk. The United States government claimed the Navajos’ livestock were overgrazing the land. In another experiment, it decided to immediately kill over 80% of their livestock in what is known as the Navajo Livestock Reduction and start a permit system.

There were people who were sympathetic to the plight of the Navajo. In 1937, Mary Cabot Wheelright and Hastiin Klah, an esteemed and influential Navajo singer, or medicine man, founded The Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian is a repository for sound recordings, manuscripts, paintings, and sandpainting tapestries of the Navajo people and a place to sense the beauty, dignity, and profound logic of Navajo religion. When Klah met Cabot in 1921, he witnessed decades of relentless efforts made by the United States government and by missionaries to assimilate the Navajo people into mainstream society. Children were removed from their homes and placed in boarding schools, where they were punished for speaking their language and forced to adopt Christianity. The museum was founded to preserve the religion and traditions of the Navajo people, which Klah was sure would soon be lost forever.

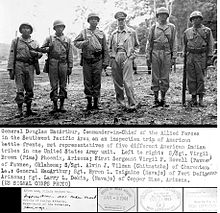

In the 1940s, during World War II, the United States denied the Navajos relief because of the Navajos’ communal society.[15] Eventually, in December 1947, the Navajos were provided relief in the post-war period to relieve the hunger that they had had to endure for many years.[16] In the 1940s, large quantity of Uranium was discovered in the land of the Navajos. From then into the early twenty-first century, the United states exploited large portions of the population, subjecting them to increased rates of death and illness from lung disease and cancer. Holistic and comprehensive compensation is yet forthcoming. [17]

Culture

The name “Navajo” comes from the late 18th century via the Spanish (Apaches de) Navajó "(Apaches of) Navajó", which was derived from the Tewa navahū "fields adjoining a ravine". The Navajo call themselves Diné, which means "the people". Nonetheless, most Navajo now acquiesce to being called "Navajo." (an older spelling of the word – "Navaho" – is not preferred by most Navajo in modern times).

Traditionally, like other Apacheans, the Navajo were semi-nomadic from the 16th through the 20th centuries. Their extended kinship groups had seasonal dwelling areas to accommodate livestock, agriculture and gathering practices. As part of their traditional economy, Navajo groups may have formed trading or raiding parties, traveling relatively long distances.

Historically, the structure of the Navajo society is largely a matrilocal system in which only women were allowed to own livestock and land. Once married, a Navajo man would move into his bride's dwelling and clan, since daughters (or, if necessary, other female relatives) were traditionally the ones who received the generational inheritance. Any children are said to belong to the mother's clan and be "born for" the father's clan. The clan system is exogamous, meaning it was, and mostly still is, considered a form of incest to marry or date anyone from any of a person's four grandparents' clans.

Traditional dwellings

A hogan is the traditional Navajo home. These eight-sided houses are made of wood and covered in mud, with the door always facing east to welcome the sun each morning. Hogans are houses made of poles and brush covered with earth.[18] Navajos have several types of hogans for lodging and ceremonial use. Ceremonies, such as healing ceremonies or the kinaalda, will take place inside a hogan.[19] According to Kehoe, this style of housing is distinctive to the Navajo, even going as far as saying that, "even today, a solidly constructed, log walled Hogan is preferred by many Navajo families." Today, however, most Navajo members live in apartments and houses in urban areas.[2]

For those who practice the Navajo religion, the hogan is considered sacred. The religious song "The Blessingway" describes the first hogan as being built by Coyote with help from beavers to be a house for First Man, First Woman, and Talking God. The Beaver People gave Coyote logs and instructions on how to build the first hogan. Navajos made their hogans in the traditional fashion until the 1900s, when they started to make them in hexagonal and octagonal shapes. Today they are rarely used as actual dwellings, but are maintained primarily for ceremonial purposes.

The Navajo people traditionally hold the four sacred mountains as the boundaries of the homeland they should never leave: Blanca Peak (Tsisnaasjini' — Dawn or White Shell Mountain) in Colorado; Mount Taylor (Tsoodzil — Blue Bead or Turquoise Mountain) in New Mexico; the San Francisco Peaks (Doko'oosliid — Abalone Shell Mountain) in Arizona; and Hesperus Mountain (Dibé Nitsaa — Big Mountain Sheep) in Colorado.

Visual arts

Silverwork

Silversmithing is an important art form among Navajo. Atsidi Sani (ca. 1830–ca. 1918) is considered to be the first Navajo silversmith. He learned silversmithing from a Mexican man called Nakai Tsosi ("Thin Mexican") around 1878 and began teaching other Navajos how to work with silver.[20] By 1880, Navajo silversmiths were creating handmade jewelry including bracelets, tobacco flasks, necklaces and bow guards. Later, they added beautiful silver earrings, buckles, bolos, hair ornaments, pins and squash blossom necklaces for tribal use, and to sell to tourists as a way to supplement their income.[21]

The Navajo's hallmark jewelry piece called the "squash blossom" necklace first appeared in the 1880s. The term "squash blossom" was apparently attached to the name of the Navajo necklace at an early date, although its bud-shaped beads are thought to derive from Spanish-Mexican pomegranate designs.[22] The Navajo silversmiths also borrowed the "naja" (najahe in Navajo[23] symbol to shape the silver pendant that hangs from the "squash blossom" necklace.

Turquoise has been part of jewelry for centuries, but Navajo artists did not use inlay techniques to insert turquoise into silver designs until the late 19th century.

Weaving

Navajo came to the southwest with their own weaving traditions; however, they learned to weave cotton on upright looms from Pueblo peoples. The first Spaniards to visit the region wrote about seeing Navajo blankets. By the 18th century the Navajo had begun to import Bayeta red yarn to supplement local black, grey, and white wool, as well as wool dyed with indigo. Using an upright loom the Navajos made extremely fine utilitarian blankets that were collected by Ute and Plains Indians. These Chief's Blankets, so called because only chiefs or very wealthy individuals could afford them, were characterized by horizontal stripes and minimal patterning in red. First Phase Chief's Blankets have only horizontal stripes, Second Phase feature red rectangular designs, and Third Phase feature red diamonds and partial diamond patterns.

The completion of the railroads dramatically changed Navajo weaving. Cheap blankets were imported, so Navajo weavers shifted their focus to weaving rugs for an increasingly non-Native audience. Rail service also brought in Germantown wool, commercial dyed wool, which greatly expanded the weavers' color palettes.

Some early American settlers moved in and set up trading posts, often buying Navajo Rugs by the pound and selling them back east by the bale. Still these traders encouraged the locals to weave blankets and rugs into distinct styles. They included "Two Gray Hills" (predominantly black and white, with traditional patterns), "Teec Nos Pos" (colorful, with very extensive patterns), "Ganado" (founded by Don Lorenzo Hubbell[24]), red dominated patterns with black and white, "Crystal" (founded by J. B. Moore), oriental and Persian styles (almost always with natural dyes), "Wide Ruins", "Chinlee", banded geometric patterns, "Klagetoh", diamond type patterns, "Red Mesa" and bold diamond patterns.[25] Many of these patterns exhibit a fourfold symmetry, which is thought to embody traditional ideas about harmony or hózhó.

Today Navajo weaving is a fine art, and weavers opt to work with natural or commercial dyes and traditional, pictorial, or a wide range of geometric designs.

Healing and spiritual practices

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2010) |

Navajo spiritual practice is about restoring health, balance, and harmony to a person's life. One exception to the concept of healing is the Beauty Way ceremony: the Kinaaldá, or a female puberty ceremony. Others include the Hooghan Blessing Ceremony and the "Baby's First Laugh Ceremony." Otherwise, ceremonies are used to heal illnesses, strengthen weakness, and give vitality to the patient. Ceremonies restore Hozhò, or beauty, harmony, balance, and health.

When suffering from illness or injury, Navajos will traditionally seek out a certified, credible Hatałii (medicine man) for healing, before turning to Western medicine (e.g., hospitals). The medicine man will use several methods to diagnose the patient's ailments. This may include using special tools such as crystal rocks, and abilities such as hand-trembling and Hatał (chanting prayer). The medicine man will then select a specific healing chant for that type of ailment. Short prayers for protection may take only a few hours, and in some cases, the patient is expected to do a follow-up afterwards. This may include the avoidance of sexual relations, personal contact, animals, certain foods, and certain activities; it is not unlike a doctor's advice.

Possible causes of ailments could be the result of violating taboos. Contact with lightning-struck objects, exposure to taboo animals such as snakes, and contact with the dead are some of reasons for healing. Protection ceremonies, especially the Blessing Way Ceremony, are used for Navajos that leave the boundaries of the four sacred mountains, and is used extensively for Navajo warriors or soldiers going to war. Upon re-entry, there is an Enemy Way Ceremony, or Nidáá', performed on the person, to get rid of the evil things in his or her body, and to restore balance in his or her life. This is also important for Navajo warriors or soldiers returning from battle. Warriors or soldiers often suffer spiritual or psychological damage from participating in warfare, and the Enemy Way Ceremony helps restore harmony to the person, mentally and emotionally.

There are also ceremonies used for curing people from curses. Many people often complain of witches and skin-walkers that do harm to their minds, bodies, and even families. Ailments aren't necessarily physical. It can take any form it wishes. The medicine man is often able to break the curses that witches and skin-walkers put on families. Mild cases do not take very long, but for extreme cases, special ceremonies are needed to drive away the evil spirits. In these cases, the medicine man may find curse objects implanted inside the victim's body. These objects are used to cause the person pain and illness. Examples of such objects include bone fragments, rocks and pebbles, bits of string, snake teeth, owl feathers, and even turquoise jewelry.

There are said to be approximately fifty-eight to sixty sacred ceremonies. Most of them last four days or more; to be most effective, they require that relatives and friends attend and help out. Outsiders are often discouraged from participating in case they become a burden to others or violate a taboo. This could affect the turnout of the ceremony. The ceremony must be done in precisely the correct manner to heal the patient. This includes everyone that is involved.

Medicine men must be able to correctly perform a ceremony from beginning to end. If he does not, the ceremony will not work. Training a Hatałii to perform ceremonies is extensive, arduous, and takes many years, and is not unlike priesthood, with the governing body or hierarchy omitted. The apprentice learns everything by watching his teacher, and memorizes the words to all the chants. Many times, a medicine man cannot learn all sixty of the ceremonies, so he will opt to specialize in a select few.

The origin of spiritual healing ceremonies dates back to Navajo mythology. It is said the first Enemy Way ceremony was performed for Changing Woman's twin sons (Monster Slayer and Born-For-the-Water) after slaying the Giants (the Yé'ii) and restoring Hozhó to the world and people. The patient identifies with Monster Slayer through the chants, prayers, sandpaintings, herbal medicine and dance.

Another Navajo healing, the Night Chant ceremony is administered as a cure for most types of head ailments, including mental disturbances. The ceremony, conducted over several days, involves purification, evocation of the gods, identification between the patient and the gods, and the transformation of the patient. Each day entails the performance of certain rites and the creation of detailed sand paintings. On the ninth evening a final all-night ceremony occurs, in which the dark male thunderbird god is evoked in a song that starts by describing his home:

- In Tsegihi [White House],

- In the house made of the dawn,

- In the house made of the evening light[26]

The medicine man proceeds by asking the Holy People to be present, then identifying the patient with the power of the god and describing the patient's transformation to renewed health with lines such as "Happily I recover"[27] The same dance is repeated throughout the night, about forty eight times. Altogether the Night Chant ceremony takes about ten hours to perform, and ends at dawn.

In the media

In 2000 the documentary The Return of Navajo Boy was shown at the Sundance Film Festival. It was written in response to an earlier film, The Navajo Boy which was somewhat exploitative of the Navajo People involved. The Return of Navajo Boy allowed the Navajo People to be more involved in the depicting of their own people.[28]

In the final episode of the third season of the FX reality TV show 30 Days, the shows producer Morgan Spurlock spends thirty days living with a Navajo family on their reservation in New Mexico. The July 2008 show called Life on an Indian Reservation, depicts the dire conditions that many Native Americans experience living on reservations in the United States.

Notable Navajo people

- Dr. Fred Begay, Native American nuclear physicist and a Korean War Veteran

- Notah Begay III (Navajo-Isleta-San Felipe Pueblo), American professional golfer

- Klee Benally, musician and documentary filmmaker[29]

- Jacoby Ellsbury, Boston Red Sox outfielder (Enrolled member of the Colorado River Indian Tribes)

- Joe Kieyoomia, captured by the Imperial Japanese Army after the fall of the Philippines in 1942

- Jay Tavare, actor

- Cory Witherill, first full-blooded Native American in NASCAR.

Notable Navajo politicians

- Mark Maryboy (Aneth/Red Mesa/Mexican Water), former NN Council Delegate and currently working in Utah Navajo Investments

- Leonard Tsosie, Navajo Tribal Councilman (Whitehorse/Torreon//Pueblo Pintado) / Former State Senator - District 22, New Mexico Senate

- Annie Dodge Wauneka, Former Navajo Tribal Councilwoman

- Peter MacDonald, Former Navajo Tribal Chairman

- Kenneth Maryboy (Aneth/Red Mesa/Mexican Water), helped initiate the Navajo Santa Program for poverty stricken Navajo families

- Joe Shirley, Jr., former President of the Navajo Nation

Notable Navajo visual artists

- Atsidi Sani (ca. 1828–1918), first known Navajo silversmith

- Harrison Begay (b. 1914), Studio painter

- Lorenzo Clayton (b. 1940), artist

- Blue Corn, potter

- R. C. Gorman (1932–2005), painter and printmaker

- Hastiin Klah, weaver and co-founder of the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian

- David Johns (b. 1948), painter

- Yazzie Johnson, contemporary silversmith

- Klah Tso (mid-19th c.—early 20th c), pioneering easel painter

- Gerald Nailor, Sr. (1917–1952), Studio painter

- Clara Nezbah Sherman, weaver

- Ryan Singer, painter, illustrator, screen printer

- Tommy Singer, silversmith and jeweler

- Quincy Tahoma (1920–1956), Studio painter

- Emmi Whitehorse, contemporary painter

- Melanie Yazzie, contemporary printmaker

Navajo writers

- Irvin Morris, author and lecturer

- Luci Tapahonso, poet and lecturer

- Elizabeth Woody, author, educator, and environmentalist

- Sherwin Bitsui, author and poet

Notable Navajo dancers and musicians

- Blackfire, punk rock band

- Raven Chacon, composer

- Radmilla Cody, traditional singer

- R. Carlos Nakai, musician

- Jock Soto, ballet dancer

- Douglas Spotted Eagle, musician

See also

- Blackfire

- Navajo (disambiguation)

- Navajo-Churro sheep

- Navajo Code Talker

- Navajo language

- Navajo-language films

- Navajo Nation

- Navajo mythology

- Navajo pueblitos

Notes

- ^ "The American Indian and Alaska Native Population: 2000" (PDF). Census 2000 Brief. 2002-02-01. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- ^ a b Kehoe, 133

- ^ Iverson, Nez, and Deer, 19

- ^ Iverson, Nez, and Deer, 20

- ^ Iverson, Nez, and Deer, 62

- ^ "Navajo Indian Language (Dine)." (retrieved 28 Nov 2010)

- ^ Watkins, Thayer. "Discovery of the Athabascan Origin of the Apache and Navajo Language." San Jose State University. (retrieved 28 Nov 2010)

- ^ First Peoples' Cultural Foundation "About Our Language." First Voices: Dene Welcome Page. 2010 (retrieved 28 Nov 2010)

- ^ Common claims of Athabaskan speakers and commonly known language evidence. For example: Shashyazzie "Little Bear' in Navajo (Shash “bear” + Yazzie “little”) is similar to the Mescalero Apache ShashZhaa (Shash “bear” + Zhaa “little”); as are "Sun" Navajo "Shá" Mescalero Apache "Shá," "Water" Navajo "Tó" Mescalero Apache "Tú," "White" Navajo "Łigaii" Mescalero Apache "Łiga," "Yellow" Navajo "Łitsooí" Mescalero Apache "Łitsu." Sources: Robert W Young, The Navajo language: The elements of Navaho grammar with a dictionary in two parts containing basic vocabularies of Navaho and English, 1943; Mescalero Apache Tribe, Mescalero Apache Dictionary, 1982; Jeff Leer, Navajo and Comparative Athabaskan Stem List, 1982

- ^ Pritzker, 52

- ^ For example, the Great Canadian Parks website suggests that the Navajo may be descendants the lost Naha tribe, a Slavey tribe from the Nahanni region west of Great Slave Lake. "Nahanni National Park Reserve". Great Canadian Parks. Retrieved 2007-07-02.

- ^ Hosteen Klah, page 102 and others

- ^ Pages 133 to 140 and 152 to 154, Sides, Blood and Thunder

- ^ Simpson, James H, edited and annotated by Frank McNitt, forward by Durwood Ball, Navaho Expedition: Journal of a Military Reconnaissance from Santa Fe, New Mexico, to the Navaho Country, Made in 1849, University of Oklahoma Press (1964), trade paperback (2003), 296 pages, ISBN 0.8061-3570-0

- ^ Nash, Gary B., Julie Roy Jeffrey, John R. Howe, Peter J. Frederick, Allen F. Davis, Allan M. Winkler, Charlene Mires, and Carla Gardina Pestana. The American People, Concise Edition Creating a Nation and a Society, Combined Volume (6th Edition), 847. New York: Longman, 2007.

- ^ Bernstein, Alison R. American Indians and World War II Toward a New Era in Indian Affairs. New York: University of Oklahoma P, 1999.

- ^ Judy Pasternak, Yellow Dirt- An American Story of a Poisoned Land and a People Betrayed, Free Press, New York, 2010.

- ^ Iverson, Nez, and Deer, 16

- ^ Iverson, Nez, and Deer, 23

- ^ Adair 4

- ^ Adair 135

- ^ Adair 44

- ^ Adair, 9

- ^ "Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site" White Mountains Online. (retrieved 28 Nov 2010)

- ^ Denver Art Museum. "Blanket Statements." Traditional Fine Arts Organization. (retrieved 28 Nov 2010)

- ^ Sandner, 88

- ^ Sandner, 90

- ^ Klee Benally

References

- Adair, John. The Navajo and Pueblo Silversmiths. Norman: Oklahoma Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0-806-12215-1.

- Iverson, Peter, Jennifer Nez Denetdale, and Ada E. Deer. The Navajo. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 2006. ISBN 0-7190-8595-3.

- Kehoe, Alice Beck. North American Indians: A Comprehensive account. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 2005.

- Newcomb, Franc Johnson (1964). Hosteen Klah: Navajo Medicine Man and Sand Painter. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. LCCCN 64-20759.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Pritzker, Barry M. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0195138771.

- Sandner, Donald. Navaho symbols of healing: a Jungian exploration of ritual, image, and medicine. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press, 1991. ISBN 0-89281-434-3.

- Sides, Hampton, Blood and Thunder: An Epic of the American West. Doubleday (2006). ISBN 978-0-385-50777-6.

Further reading

- Bailey, L. R. (1964). The Long Walk: A History of the Navaho Wars, 1846–1868.

- Bighorse, Tiana (1990). Bighorse the Warrior. Ed. Noel Bennett, Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- Brugge, David M. (1968). Navajos in the Catholic Church Records of New Mexico 1694–1875. Window Rock, Arizona: Research Section, The Navajo Tribe.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Clarke, Dwight L. (1961). Stephen Watts Kearny: Soldier of the West. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Downs, James F. (1972). The Navajo. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

- Dyke, Walter (1967) [1938]. Son of Old Man Hat. Lincoln, Nebraska: Bison Books & University of Nebraska Press. LCCN 44-2654.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Forbes, Jack D. (1960). Apache, Navajo and Spaniard. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. LCCN 60-13480.

- Hammond, George P. and Rey, Agapito (editors) (1940). Narratives of the Coronado Expedition 1540–1542. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- Iverson, Peter (2002). Diné: A History of the Navahos. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-2714-1.

- Kelly, Lawrence (1970). Navajo Roundup Pruett Pub. Co., Colorado.

- Linford, Laurence D. (2000). Navajo Places: History, Legend, Landscape. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. ISBN 978-0-87480-624-3

- McNitt, Frank (1972). Navajo Wars. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- Plog, Stephen Ancient Peoples of the American Southwest. Thames and London, LTD, London, England, 1997. ISBN 0-500-27939-X.

- Roessel, Ruth (editor) (1973). Navajo Stories of the Long Walk Period. Tsaile, Arizona: Navajo Community College Press.

- Roessel, Ruth, ed. (1974). Navajo Livestock Reduction: A National Disgrace. Tsaile, Arizona: Navajo Community College Press. ISBN 0-912586-18-4.

- Witherspoon, Gary (1977). Language and Art in the Navajo Universe. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Witte, Daniel. Removing Classrooms from the Battlefield: Liberty, Paternalism, and the Redemptive Promise of Educational Choice, 2008 BYU Law Review 377 The Navajo and Richard Henry Pratt

- Zaballos, Nausica (2009). Le système de santé navajo. Paris: L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-296-07975-5.

External links

- Nation Nation, official site

- Navajo Tourism Department

- Navajo people: history, culture, language, art

- Middle Ground Project of Northern Colorado University with images of U.S. documents of treaties and reports 1846–1931

- Navajo Silversmiths, by Washington Matthews, 1883 from Project Gutenberg

- Navajo Institute for Social Justice

- Navajo weaving

- Non-Profit Navajo Arts & Crafts Enterprise

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.