Islamic Golden Age

This article has been shortened from a longer article which misused sources. |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2011) |

- This is a sub-article to Islamic history and Islamic science.

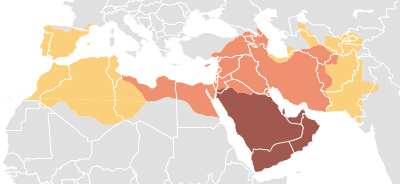

During the Islamic Golden Age (c.750 CE - c.1258 CE) philosophers, scientists and engineers of the Islamic world contributed enormously to technology, both by preserving earlier traditions and by adding their own inventions and innovations. Scientific and intellectual achievements blossomed in the Golden age.

Foundations

Bernard Lewis wrote that Islamic governments inherited:

the knowledge and skills of the ancient Middle East, of Greece and of Persia. They added new and important innovations from outside, such as the manufacture of paper from China and decimal positional numbering from India.[1]

Much of this learning and development can be linked to geography. Even prior to Islam's presence, the city of Mecca served as a center of trade in Arabia and Muhammad was a merchant. The tradition of the pilgrimage to Mecca became a center for exchanging ideas and goods. The influence held by Muslim merchants over African-Arabian and Arabian-Asian trade routes was tremendous. As a result, Islamic civilization grew and expanded on the basis of its merchant economy, in contrast to their Christian, Indian and Chinese peers who built societies from an agricultural landholding nobility. Merchants brought goods and their faith to China (resulting in a significant population of Chinese Muslims with an estimated 37 million followers, mainly ethnic Turkic Uyghur whose territory was annexed to China), India, southeast Asia, and the kingdoms of western Africa and returned with new inventions.

Islamic art

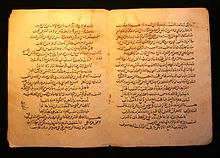

The golden age of Islamic (and/or Muslim) art lasted from 750 to the 16th century, when ceramics (especially lusterware), glass, metalwork, textiles, illuminated manuscripts, and woodwork flourished. Manuscript illumination became an important and greatly respected art, and portrait miniature painting flourished in Persia. Calligraphy, an essential aspect of written Arabic, developed in manuscripts and architectural decoration.

Philosophy

Only in philosophy were Islamic scholars prevented from putting forth unorthodox ideas. Nevertheless, Ibn Rushd and Persian polymath Avicenna played a major role in saving the works of Aristotle, whose ideas came to dominate the non-religious thought of the Christian and Muslim worlds. They would also absorb ideas from China, and India, adding to them tremendous knowledge from their own studies. Three speculative thinkers, al-Kindi, al-Farabi, and Avicenna, combined Aristotelianism and Neoplatonism with other ideas introduced through Islam.

From Spain the Arabic philosophic literature was translated into Hebrew, Latin, and Ladino, contributing to the development of modern European philosophy. The Jewish philosopher Moses Maimonides, sociologist-historian Ibn Khaldun, Carthage citizen Constantine the African who translated Greek medical texts and Al-Khwarzimi's collation of mathematical techniques were important figures of the Golden Age.

Sciences

Many notable Islamic scientists lived and practiced during the Islamic Golden Age. Among the achievements of Muslim scholars during this period were the development of spherical trigonometry into its modern form (greatly simplifying its practical application to calculate the phases of the moon), advances in optics, and advances in astronomy.

Medicine

Medicine was a central part of medieval Islamic culture. Responding to circumstances of time and place, Islamic physicians and scholars developed a large and complex medical literature exploring and synthesizing the theory and practice of medicine. (from the National Library of Medicine digital archives)

Islamic medicine was built on tradition, chiefly the theoretical and practical knowledge developed in Greece, Rome, and Persia. For Islamic scholars, Galen and Hippocrates were pre-eminent authorities, followed by Hellenic scholars in Alexandria. Islamic scholars translated their voluminous writings from Greek into Arabic and then produced new medical knowledge based on those texts. In order to make the Greek tradition more accessible, understandable, and teachable, Islamic scholars ordered and made more systematic the vast and sometimes inconsistent Greco-Roman medical knowledge by writing encyclopedias and summaries. (from the National Library of Medicine digital archives)

Pagan Latin and Greek learning was viewed suspiciously in Christian early medieval Europe, and it was through 12th century Arabic translations that medieval Europe rediscovered Hellenic medicine, including the works of Galen and Hippocrates. Of equal if not of greater influence in Western Europe were systematic and comprehensive works such as Avicenna's The Canon of Medicine, which were translated into Latin and then disseminated in manuscript and printed form throughout Europe. During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries alone, The Canon of Medicine was published more than thirty-five times. (from the National Library of Medicine digital archives)

In the medieval Islamic world, hospitals were built in all major cities; in Cairo for example, the Qalawun hospital had a staff that included physicians, pharmacists, and nurses. One could also access a dispensary, and research facility that led to advances in understanding contagious diseases, and research into optics and the mechanisms of the eye. Muslim doctors were the first to use hollow needles to remove cataracts.

Commerce and travel

Apart from the Nile, Tigris and Euphrates, navigable rivers were uncommon, so transport by sea was very important. Navigational sciences were highly developed, making use of a rudimentary sextant (known as a kamal). When combined with detailed maps of the period, sailors were able to sail across oceans rather than skirt along the coast. Muslim sailors were also responsible for reintroducing large three masted merchant vessels to the Mediterranean. The name caravel may derive from an earlier Arab boat known as the qārib.[2] An artificial canal linking the Nile with the Gulf of Suez was constructed, linking the Red Sea with the Mediterranean[citation needed] (although it silted up several times).

During the Islamic Golden Age, travel to distant lands took place. The use of paper spread from China into the Muslim world in the eighth century CE, arriving in Spain (and then the rest of Europe) in the 10th century CE. It was easier to manufacture than parchment, less likely to crack than papyrus, and could absorb ink, making it ideal for making records and making copies of the Koran. "Islamic paper makers devised assembly-line methods of hand-copying manuscripts to turn out editions far larger than any available in Europe for centuries."[3] It was from Islam that the rest of the world learned to make paper from linen.[4] (from the digital archives of The National Library of Medicine)

Architecture and engineering

The Great Mosque of Kairouan (in Tunisia), the ancestor of all the mosques in the western Islamic world,[6] is one of the best preserved and most significant examples of early great mosques. Founded in 670, it dates in its present form largely from the 9th century.[7] The Great Mosque of Kairouan is constituted of a three-tiered square minaret, a large courtyard surrounded by colonnaded porticos and a huge hypostyle prayer hall covered on its axis by two cupolas.[6]

The Great Mosque of Samarra in Iraq was completed in 847. It combined the hypostyle architecture of rows of columns supporting a flat base above which a huge spiralling minaret was constructed.

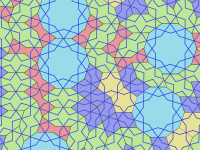

The Moors began construction of the Great Mosque at Cordoba in 785 marking the beginning of Islamic architecture in Spain and Northern Africa (see Moors). The mosque is noted for its striking interior arches. Moorish architecture reached its peak with the construction of the Alhambra, the magnificent palace/fortress of Granada, with its open and breezy interior spaces adorned in red, blue, and gold. The walls are decorated with stylized foliage motifs, Arabic inscriptions, and arabesque design work, with walls covered in glazed tiles.

Another distinctive sub-style is the architecture of the Mughal Empire in India in the 16th century. Blending Islamic and Hindu elements, the emperor Akbar constructed the royal city of Fatehpur Sikri, located 26 miles west of Agra, in the late 1500s.

Mongolian invasion and gradual decline

The Crusades put the Islamic world under pressure by invasion in the 11th and 12th centuries, but a new and far greater threat came from the East during the 13th century: in 1206, Genghis Khan established a powerful dynasty among the Mongols of central Asia. During the 13th century, this Mongol Empire conquered most of the Eurasian land mass, including both China in the east and much of the old Islamic caliphate (as well as Kievan Rus) in the west. Hulagu Khan's destruction of Baghdad in 1258 is traditionally seen as the approximate end of the Golden Age. Later Mongol leaders, such as Timur, destroyed many cities, slaughtered hundreds of thousands of people, and did irrevocable damage to the ancient irrigation systems of Mesopotamia. Muslims in lands subject to the Mongols now faced northeast, toward the land routes to China, rather than toward Mecca.

Eventually, most of the Mongol peoples that settled in western Asia converted to Islam and in many instances became assimilated into various Muslim Turkic peoples. The Ottoman Empire rose from the ashes, but (according to the traditional view) the Golden Age was over.

Causes of decline

There is little agreement on the precise causes of the decline, but in addition to invasion by the Mongols and crusaders and the destruction of libraries and madrasahs, it has also been suggested that political mismanagement and the stifling of ijtihad (independent reasoning) in the 12th century in favor of institutionalised taqleed (imitation) thinking played a part. Ahmad Y Hassan has rejected the thesis that lack of creative thinking was a cause, arguing that science was always kept separate from religious argument; he instead analyses the decline in terms of economic and political factors, drawing on the work of the 14th Century writer Ibn Khaldun.[8]

Opposing views

Some commentators have disputed the importance of the Golden Age, going as far as to call it a myth, intended to distract attention from modern Islam. Srdja Trifkovic's book The Sword of the Prophet is highly critical of Islam in the Golden Age. It is indisputable that Islamic regimes, such as the Abbasid Caliphate of Baghdad under Harun ar-Rashid or al-Andalus were very wealthy in comparison with their neighbours, preserved a large amount of Greek philosophy, and transmitted Eastern ideas such as the concept of zero ('0'), believed to have been developed in India. (See also: Arabic numerals). However, some critics[who?] claim that all this flourished in spite of Islam rather than because of it, arguing that the caliphate and other Islamic governments emphasized rigid interpretation of Qur'anic orthodoxy, deploying Greek philosophy and science solely to buttress its authority. As in Christendom, persecution, exile and death were frequently meted out to philosophers whose writings did not conform to the canon. [citation needed]

The issue of Islamic Civilization being a misnomer has also been raised by a number of recent scholars, including the secular Iranian historian, Dr. Shoja-e-din Shafa in his recent controversial books titled Rebirth (Persian: تولدى ديگر) and After 1400 Years (Persian: پس از 1400 سال), in which he questions whether it makes sense to talk of a category such as “Islamic science”. Shafa states that while religion has been a cardinal foundation for nearly all empires of antiquity to derive their authority from, it does not possess adequate defining factors to justify attribution in the development of science, technology, and arts to the existence and practice of a certain faith within a particular realm. While various empires in the course of mankind's history had an official religion, we do not normally ascribe their achievements to the faith they practiced. For example, the achievements of the Christian Roman Empire, Byzantine Empire and all subsequent European empires that advocated Christianity are not normally considered one civilization.

See also

- Timeline of Islamic science and technology

- Islamic studies

- Islamic scholars

- Islamic medicine

- Islamic science

- Ophthalmology in medieval Islam

- Astronomy in Islam

- List of Iranian scientists

- Golden age of Jewish culture in Spain

Notes

- ^ What Went Wrong?, Lewis, 2002

- ^ "History of the caravel". Nautarch.tamu.edu. Retrieved 2011-04-13.

- ^ Islam's Gift of Paper to the West

- ^ Kevin M. Dunn, Caveman chemistry : 28 projects, from the creation of fire to the production of plastics, Universal-Publishers, 2003, page 166

- ^ Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Islamic art and spirituality, SUNY Press, 1987, page 53

- ^ a b John Stothoff Badeau and John Richard Hayes, The Genius of Arab civilization: source of Renaissance. Taylor & Francis. 1983. p. 104

- ^ Great Mosque of Kairouan (Qantara mediterranean heritage)

- ^ Ahmad Y Hassan, Factors Behind the Decline of Islamic Science After the Sixteenth Century

References

- Donald R. Hill, Islamic Science And Engineering, Edinburgh University Press (1993), ISBN 0748604553