Monopoly

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2009) |

| Competition law |

|---|

|

| Basic concepts |

| Anti-competitive practices |

|

| Enforcement authorities and organizations |

A monopoly (from Greek monos / μονος (alone or single) + polein / πωλειν (to sell)) exists when a specific person or enterprise is the only supplier of a particular commodity. (This contrasts with a monopsony which relates to a single entity's control of a market to purchase a good or service, and with oligopoly which consists of a few entities dominating an industry)[1] [clarification needed] Monopolies are thus characterized by a lack of economic competition to produce the good or service and a lack of viable substitute goods.[2] The verb "monopolise" refers to the process by which a company gains much greater market share than what is expected with perfect competition.

A monopoly is distinguished from a monopsony, in which there is only one buyer of a product or service ; a monopoly may also have monopsony control of a sector of a market. Likewise, a monopoly should be distinguished from a cartel (a form of oligopoly), in which several providers act together to coordinate services, prices or sale of goods. Monopolies, monopsonies and oligopolies are all situations such that one or a few of the entities have market power and therefore interact with their customers (monopoly), suppliers (monopsony) and the other companies (oligopoly) in a game theoretic manner – meaning that expectations about their behavior affects other players' choice of strategy and vice versa. This is to be contrasted with the model of perfect competition in which companies are "price takers" and do not have market power.

When not coerced legally to do otherwise, monopolies typically maximize their profit by producing fewer goods and selling them at higher prices than would be the case for perfect competition. (See also Bertrand, Cournot or Stackelberg equilibria, market power, market share, market concentration, Monopoly profit, industrial economics). Sometimes governments decide legally that a given company is a monopoly that doesn't serve the best interests of the market and/or consumers. Governments may force such companies to divide into smaller independent corporations as was the case of United States v. AT&T, or alter its behavior as was the case of United States v. Microsoft, to protect consumers.

Monopolies can be established by a government, form naturally, or form by mergers. A monopoly is said to be coercive when the monopoly actively prohibits competitors by using practices (such as underselling) which derive from its market or political influence (see Chainstore paradox). There is often debate of whether market restrictions are in the best long-term interest of present and future consumers.

In many jurisdictions, competition laws restrict monopolies. Holding a dominant position or a monopoly of a market is not illegal in itself, however certain categories of behavior can, when a business is dominant, be considered abusive and therefore incur legal sanctions. A government-granted monopoly or legal monopoly, by contrast, is sanctioned by the state, often to provide an incentive to invest in a risky venture or enrich a domestic interest group. Patents, copyright, and trademarks are all examples of government granted and enforced monopolies. The government may also reserve the venture for itself, thus forming a government monopoly.

Market structures

In economics, the idea of monopoly is important for the study of market structures, which directly concerns normative aspects of economic competition, and provides the basis for topics such as industrial organization and economics of regulation. There are four basic types of market structures by traditional economic analysis: perfect competition, monopolistic competition, oligopoly and monopoly. A monopoly is a market structure in which a single supplier produces and sells a given product. If there is a single seller in a certain industry and there are not any close substitutes for the product, then the market structure is that of a "pure monopoly". Sometimes, there are many sellers in an industry and/or there exist many close substitutes for the goods being produced, but nevertheless companies retain some market power. This is termed monopolistic competition, whereas by oligopoly the companies interact strategically.

In general, the main results from this theory compare price-fixing methods across market structures, analyze the effect of a certain structure on welfare, and vary technological/demand assumptions in order to assess the consequences for an abstract model of society. Most economic textbooks follow the practice of carefully explaining the perfect competition model, only because of its usefulness to understand "departures" from it (the so-called imperfect competition models).

The boundaries of what constitutes a market and what doesn't are relevant distinctions to make in economic analysis. In a general equilibrium context, a good is a specific concept entangling geographical and time-related characteristics (grapes sold during October 2009 in Moscow is a different good from grapes sold during October 2009 in New York). Most studies of market structure relax a little their definition of a good, allowing for more flexibility at the identification of substitute-goods. Therefore, one can find an economic analysis of the market of grapes in Russia, for example, which is not a market in the strict sense of general equilibrium theory monopoly.

Characteristics

- Profit Maximiser: Maximizes profits.

- Price Maker: Decides the price of the good or product to be sold.

- High Barriers to Entry: Other sellers are unable to enter the market of the monopoly.

- Single seller: In a monopoly there is one seller of the good which produces all the output.[3] Therefore, the whole market is being served by a single company, and for practical purposes, the company is the same as the industry.

- Price Discrimination: A monopolist can change the price and quality of the product. He sells more quantities charging less price for the product in a very elastic market and sells less quantities charging high price in a less elastic market.

Sources of monopoly power

Monopolies derive their market power from barriers to entry – circumstances that prevent or greatly impede a potential competitor's ability to compete in a market. There are three major types of barriers to entry; economic, legal and deliberate.[4]

- Economic barriers: Economic barriers include economies of scale, capital requirements, cost advantages and technological superiority.[5]

- Economies of scale: Monopolies are characterised by decreasing costs for a relatively large range of production.[6] Decreasing costs coupled with large initial costs give monopolies an advantage over would-be competitors. Monopolies are often in a position to reduce prices below a new entrant's operating costs and thereby prevent them from continuing to compete.[6] Furthermore, the size of the industry relative to the minimum efficient scale may limit the number of companies that can effectively compete within the industry. If for example the industry is large enough to support one company of minimum efficient scale then other companies entering the industry will operate at a size that is less than MES, meaning that these companies cannot produce at an average cost that is competitive with the dominant company. Finally, if long-term average cost is constantly decreasing, the least cost method to provide a good or service is by a single company.[7]

- Capital requirements: Production processes that require large investments of capital, or large research and development costs or substantial sunk costs limit the number of companies in an industry.[8] Large fixed costs also make it difficult for a small company to enter an industry and expand.[9]

- Technological superiority: A monopoly may be better able to acquire, integrate and use the best possible technology in producing its goods while entrants do not have the size or finances to use the best available technology.[6] One large company can sometimes produce goods cheaper than several small companies.[10]

- No substitute goods: A monopoly sells a good for which there is no close substitute. The absence of substitutes makes the demand for the good relatively inelastic enabling monopolies to extract positive profits.

- Control of natural resources: A prime source of monopoly power is the control of resources that are critical to the production of a final good.

- Network externalities: The use of a product by a person can affect the value of that product to other people. This is the network effect. There is a direct relationship between the proportion of people using a product and the demand for that product. In other words the more people who are using a product the greater the probability of any individual starting to use the product. This effect accounts for fads and fashion trends.[11] It also can play a crucial role in the development or acquisition of market power. The most famous current example is the market dominance of the Microsoft operating system in personal computers.

- Legal barriers: Legal rights can provide opportunity to monopolise the market of a good. Intellectual property rights, including patents and copyrights, give a monopolist exclusive control of the production and selling of certain goods. Property rights may give a company exclusive control of the materials necessary to produce a good.

- Deliberate actions: A company wanting to monopolise a market may engage in various types of deliberate action to exclude competitors or eliminate competition. Such actions include collusion, lobbying governmental authorities, and force (see anti-competitive practices).

In addition to barriers to entry and competition, barriers to exit may be a source of market power. Barriers to exit are market conditions that make it difficult or expensive for a company to end its involvement with a market. Great liquidation costs are a primary barrier for exiting.[12] Market exit and shutdown are separate events. The decision whether to shut down or operate is not affected by exit barriers. A company will shut down if price falls below minimum average variable costs.

Monopoly versus competitive markets

While monopoly and perfect competition mark the extremes of market structures[13] there is some similarity. The cost functions are the same.[14] Both monopolies and perfectly competitive companies minimize cost and maximize profit. The shutdown decisions are the same. Both are assumed to have perfectly competitive factors markets. There are distinctions, some of the more important of which are as follows:

- Marginal revenue and price - In a perfectly competitive market price equals marginal revenue. In a monopolistic market marginal revenue is less than price.[15]

- Product differentiation: There is zero product differentiation in a perfectly competitive market. Every product is perfectly homogeneous and a perfect substitute for any other. With a monopoly, there is great to absolute product differentiation in the sense that there is no available substitute for a monopolized good. The monopolist is the sole supplier of the good in question.[16] A customer either buys from the monopolizing entity on its terms or does without.

- Number of competitors: PC markets are populated by an infinite number of buyers and sellers. Monopoly involves a single seller.[16]

- Barriers to Entry - Barriers to entry are factors and circumstances that prevent entry into market by would-be competitors and limit new companies from operating and expanding within the market. PC markets have free entry and exit. There are no barriers to entry, exit or competition. Monopolies have relatively high barriers to entry. The barriers must be strong enough to prevent or discourage any potential competitor from entering the market.

- Elasticity of Demand - The price elasticity of demand is the percentage change of demand caused by a one percent change of relative price. A successful monopoly would have a relatively inelastic demand curve. A low coefficient of elasticity is indicative of effective barriers to entry. A PC company has a perfectly elastic demand curve. The coefficient of elasticity for a perfectly competitive demand curve is infinite.

- Excess Profits- Excess or positive profits are profit more than the normal expected return on investment. A PC company can make excess profits in the short term but excess profits attract competitors which can enter the market freely and decrease prices, eventually reducing excess profits to zero.[17] A monopoly can preserve excess profits because barriers to entry prevent competitors from entering the market.[18]

- Profit Maximization - A PC company maximizes profits by producing such that price equals marginal costs. A monopoly maximises profits by producing where marginal revenue equals marginal costs.[19] The rules are not equivalent. The demand curve for a PC company is perfectly elastic - flat. The demand curve is identical to the average revenue curve and the price line. Since the average revenue curve is constant the marginal revenue curve is also constant and equals the demand curve, Average revenue is the same as price (AR = TR/Q = P x Q/Q = P). Thus the price line is also identical to the demand curve. In sum, D = AR = MR = P.

- P-Max quantity, price and profit - If a monopolist obtains control of a formerly perfectly competitive industry, the monopolist would increase prices, reduce production, and realise positive economic profits.[20]

- Supply Curve - in a perfectly competitive market there is a well defined supply function with a one to one relationship between price and quantity supplied.[21] In a monopolistic market no such supply relationship exists. A monopolist cannot trace a short term supply curve because for a given price there is not a unique quantity supplied. As Pindyck and Rubenfeld note a change in demand "can lead to changes in prices with no change in output, changes in output with no change in price or both." [22] Monopolies produce where marginal revenue equals marginal costs. For a specific demand curve the supply "curve" would be the price/quantity combination at the point where marginal revenue equals marginal cost. If the demand curve shifted the marginal revenue curve would shift as well and a new equilibrium and supply "point" would be established. The locus of these points would not be a supply curve in any conventional sense.[23][24]

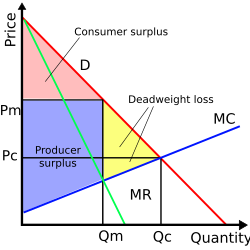

The most significant distinction between a PC company and a monopoly is that the monopoly has a downward-sloping demand curve rather than the "perceived" perfectly elastic curve of the PC company.[25] Practically all the variations above mentioned relate to this fact. If there is a downward-sloping demand curve then by necessity there is a distinct marginal revenue curve. The implications of this fact are best made manifest with a linear demand curve. Assume that the inverse demand curve is of the form x = a - by. Then the total revenue curve is TR = ay - by2 and the marginal revenue curve is thus MR = a - 2by. From this several things are evident. First the marginal revenue curve has the same y intercept as the inverse demand curve. Second the slope of the marginal revenue curve is twice that of the inverse demand curve. Third the x intercept of the marginal revenue curve is half that of the inverse demand curve. What is not quite so evident is that the marginal revenue curve is below the inverse demand curve at all points.[25] Since all companies maximise profits by equating MR and MC it must be the case that at the profit maximizing quantity MR and MC are less than price which further implies that a monopoly produces less quantity at a higher price than if the market were perfectly competitive.

The fact that a monopoly has a downward-sloping demand curve means that the relationship between total revenue and output for a monopoly is much different than that of competitive companies.[26] Total revenue equals price times quantity. A competitive company has a perfectly elastic demand curve meaning that total revenue is proportional to output.[27] Thus the total revenue curve for a competitive company is a ray with a slope equal to the market price.[27] A competitive company can sell all the output it desires at the market price. For a monopoly to increase sales it must reduce price. Thus the total revenue curve for a monopoly is a parabola that begins at the origin and reaches a maximum value then continuously decreases until total revenue is again zero.[28] Total revenue has its maximum value when the slope of the total revenue function is zero. The slope of the total revenue function is marginal revenue. So the revenue maximizing quantity and price occur when MR = 0. For example assume that the monopoly’s demand function is P = 50 - 2Q. The total revenue function would be TR = 50Q - 2Q2 and marginal revenue would be 50 - 4Q. Setting marginal revenue equal to zero we have

- 50 - 4Q = 0

- -4Q = -50

- Q = 12.5

So the revenue maximizing quantity for the monopoly is 12.5 units and the revenue maximizing price is 25.

A company with a monopoly does not experience price pressure from competitors, although it may experience pricing pressure from potential competition. If a company increases prices too much, then others may enter the market if they are able to provide the same good, or a substitute, at a lesser price.[29] The idea that monopolies in markets with easy entry need not be regulated against is known as the "revolution in monopoly theory".[30]

A monopolist can extract only one premium,[clarification needed] and getting into complementary markets does not pay. That is, the total profits a monopolist could earn if it sought to leverage its monopoly in one market by monopolizing a complementary market are equal to the extra profits it could earn anyway by charging more for the monopoly product itself. However, the one monopoly profit theorem is not true if customers in the monopoly good are stranded or poorly informed, or if the tied good has high fixed costs.

A pure monopoly has the same economic rationality of perfectly competitive companies, i.e. to optimise a profit function given some constraints. By the assumptions of increasing marginal costs, exogenous inputs' prices, and control concentrated on a single agent or entrepreneur, the optimal decision is to equate the marginal cost and marginal revenue of production. Nonetheless, a pure monopoly can -unlike a competitive company- alter the market price for its own convenience: a decrease of production results in a higher price. In the economics' jargon, it is said that pure monopolies have "a downward-sloping demand". An important consequence of such behaviour is worth noticing: typically a monopoly selects a higher price and lesser quantity of output than a price-taking company; again, less is available at a higher price.[31]

The inverse elasticity rule

A monopoly chooses that price that maximizes the difference between total revenue and total cost. The basic markup rule can be expressed as (P - MC)/P = 1/PED.[32] The markup rules indicate that the ratio between profit margin and the price is inversely proportional to the price elasticity of demand.[33] The implication of the rule is that the more elastic the demand for the product the less pricing power the monopoly has. This is also known as 1/Lerner Index

Market power

Market power is the ability to increase the product's price above marginal cost without losing all customers.[34] Perfectly competitive (PC) companies have zero market power when it comes to setting prices. All companies of a PC market are price takers. The price is set by the interaction of demand and supply at the market or aggregate level. Individual companies simply take the price determined by the market and produce that quantity of output that maximizes the company's profits. If a PC company attempted to increase prices above the market level all its customers would abandon the company and purchase at the market price from other companies. A monopoly has considerable although not unlimited market power. A monopoly has the power to set prices or quantities although not both.[35] A monopoly is a price maker.[36] The monopoly is the market[37] and prices are set by the monopolist based on his circumstances and not the interaction of demand and supply. The two primary factors determining monopoly market power are the company's demand curve and its cost structure.[38]

Market power is the ability to affect the terms and conditions of exchange so that the price of a product is set by a single company (price is not imposed by the market as in perfect competition).[39][40] Although a monopoly's market power is great it is still limited by the demand side of the market. A monopoly has a negatively sloped demand curve, not a perfectly inelastic curve. Consequently, any price increase will result in the loss of some customers.

Price discrimination

Improved price discrimination allows a monopolist to gain more profit by charging more to those who want or need the product more or who have a greater ability to pay. For example, most economic textbooks cost more in the United States than in "Third world countries" like Ethiopia. In this case, the publisher is using their government granted copyright monopoly to price discriminate between (presumed) wealthier economics students and (presumed) poor economics students. Similarly, most patented medications cost more in the U.S. than in other countries with a (presumed) poorer customer base. Perfect price discrimination would allow the monopolist to a unique price to each customer based on their individual demand. This would allow the monopolist to extract all the consumer surplus of the market. Note that while such perfect price discrimination is still a theoretical construct, it is becoming increasingly real with advances of information technology and micromarketing. Typically, a high general price is listed, and various market segments get varying discounts. This is an example of framing to make the process of charging some people higher prices more socially acceptable. (see also behavioral economics, decision biases).

It is important to realize that partial price discrimination can cause some customers who are inappropriately pooled with high price customers to be excluded from the market. For example, a poor student in the U.S. might be excluded from purchasing an economics textbook at the U.S. price, which the student might have been able to purchase at the China price. Similarly, a wealthy student in China might have been willing to pay more (although naturally it is against their interests to signal this to the monopolist). These are deadweight losses and decrease a monopolist's profits. As such, monopolists have substantial economic interest in improving their market information, and market segmenting.

There is important information for one to remember when considering the monopoly model diagram (and its associated conclusions) displayed here. The result that monopoly prices are higher, and production output lesser, than a competitive company follow from a requirement that the monopoly not charge different prices for different customers. That is, the monopoly is restricted from engaging in price discrimination (this is termed first degree price discrimination, such that all customers are charged the same amount). If the monopoly were permitted to charge individualised prices (this is termed third degree price discrimination), the quantity produced, and the price charged to the marginal customer, would be identical to that of a competitive company, thus eliminating the deadweight loss; however, all gains from trade (social welfare) would accrue to the monopolist and none to the consumer. In essence, every consumer would be indifferent between (1) going completely without the product or service and (2) being able to purchase it from the monopolist.

As long as the price elasticity of demand for most customers is less than one in absolute value, it is advantageous for a company to increase its prices: it then receives more money for fewer goods. With a price increase, price elasticity tends to increase, and in the optimum case above it will be greater than one for most customers.

Price discrimination is charging different consumers different prices for the same product when the cost of servicing the customer is identical.[41][42] A company maximizes profit by selling where marginal revenue equals marginal cost. A company that does not engage in price discrimination will charge the profit maximizing price, P*, to all its customers. In such circumstances there are customers who would be willing to pay a higher price than P* and those who will not pay P* but would buy at a lower price. A price discrimination strategy is to charge less price sensitive buyers a higher price and the more price sensitive buyers a lower price.[43] Thus additional revenue is generated from two sources. The basic problem is to identify customers by their willingness to pay.

The purpose of price discrimination is to transfer consumer surplus to the producer.[44] Consumer surplus is the difference between the value of a good to a consumer and the price the consumer must pay in the market to purchase it. [45] Price discrimination is not limited to monopolies.

Market power is a company’s ability to increase prices without losing all its customers. Any company that has market power can engage in price discrimination. Perfect competition is the only market form in which price discrimination would be impossible (a perfectly competitive company has a perfectly elastic demand curve and has zero market power). [46][47][44][48][49]

There are three forms of price discrimination. First degree price discrimination charges each consumer the maximum price the consumer is willing to pay. Second degree price discrimination involves quantity discounts. Third degree price discrimination involves grouping consumers according to willingness to pay as measured by their price elasticities of demand and charging each group a different price. Third degree price discrimination is the most prevalent type.

There are three conditions that must be present for a company to engage in successful price discrimination. First, the company must have market power.[50] Second, the company must be able to sort customers according to their willingness to pay for the good.[51] Third, the firm must be able to prevent resell.

A company must have some degree of market power to practice price discrimination. Without market power a company cannot charge more than the market price.[52] Any market structure characterized by a downward sloping demand curve has market power - monopoly, monopolistic competition and oligopoly.[53] The only market structure that has no market power is perfect competition.[54]

A company wishing to practice price discrimination must be able to prevent middlemen or brokers from acquiring the consumer surplus for themselves. The company accomplishes this by preventing or limiting resale. Many methods are used to prevent resale. For example persons are required to show photographic identification and a boarding pass before boarding an airplane. Most travelers assume that this practice is strictly a matter of security. However, a primary purpose in requesting photographic identification is to confirm that the ticket purchaser is the person about to board the airplane and not someone who has repurchased the ticket from a discount buyer.

The inability to prevent resale is the largest obstacle to successful price discrimination.[55] Companies have however developed numerous methods to prevent resale. For example, universities require that students show identification before entering sporting events. Governments may make it illegal to resale tickets or products. In Boston Red Sox tickets can only be resold legally to the team.

The three basic forms of price discrimination are first, second and third degree price discrimination. In first degree price discrimination the company charges the maximum price each customer is willing to pay. The maximum price a consumer is willing to pay for a unit of the good is the reservation price. Thus for each unit the seller tries to set the price equal to the consumer’s reservation price.[56] Direct information about a consumer’s willingness to pay is rarely available. Sellers tend to rely on secondary information such as where a person lives (postal codes); for example, catalog retailers can use mail high-priced catalogs to high-income postal codes. [57][58] First degree price discrimination most frequently occurs in regard to professional services or in transactions involving direct buyer/seller negotiations. For example, an accountant who has prepared a consumer's tax return has information that can be used to charge customers based on an estimate of their ability to pay.[59]

In second degree price discrimination or quantity discrimination customers are charged different prices based on how much they buy. There is a single price schedule for all consumers but the prices vary depending on the quantity of the good bought.[60] The theory of second degree price discrimination is a consumer is willing to buy only a certain quantity of a good at a given price. Companies know that consumer’s willingness to buy decreases as more units are purchased. The task for the seller is to identify these price points and to reduce the price once one is reached in the hope that a reduced price will trigger additional purchases from the consumer. For example, sell in unit blocks rather than individual units.

In third degree price discrimination or multi-market price discrimination [61] the seller divides the consumers into different groups according to their willingness to pay as measured by their price elasticity of demand. Each group of consumers effectively becomes a separate market with its own demand curve and marginal revenue curve.[62] The firm then attempts to maximize profits in each segment by equating MR and MC,[50][63][64] Generally the company charges a higher price to the group with a more price inelastic demand and a relatively lesser price to the group with a more elastic demand.[65] Examples of third degree price discrimination abound. Airlines charge higher prices to business travelers than to vacation travelers. The reasoning is that the demand curve for a vacation traveler is relatively elastic while the demand curve for a business traveler is relatively inelastic. Any determinant of price elasticity of demand can be used to segment markets. For example, seniors have a more elastic demand for movies than do young adults because they generally have more free time. Thus theaters will offer discount tickets to seniors.[66]

Example

Assume that by a uniform pricing system the monopolist would sell five units at a price of $10 per unit. Assume that his marginal cost is $5 per unit. Total revenue would be $50, total costs would be $25 and profits would be $25. If the monopolist practiced price discrimination he would sell the first unit for $50 the second unit for $40 and so on. Total revenue would be $150, his total cost would be $25 and his profit would be $125.00.[67] Several things are worth noting. The monopolist acquires all the consumer surplus and eliminates practically all the deadweight loss because he is willing to sell to anyone who is willing to pay at least the marginal cost.[68] Thus the price discrimination promotes efficiency. Secondly, by the pricing scheme price = average revenue and equals marginal revenue. That is the monopolist is behaving like a perfectly competitive company.[69] Thirdly, the discriminating monopolist produces a larger quantity than the monopolist operating by a uniform pricing scheme.[70]

| Qd | Price |

|---|---|

| 1 | 50 |

| 2 | 40 |

| 3 | 30 |

| 4 | 20 |

| 5 | 10 |

Classifying customers

Successful price discrimination requires that companies separate consumers according to their willingness to buy. Determining a customer's willingness to buy a good is difficult. Asking consumers directly is fruitless: consumers don't know, and to the extent they do they are reluctant to share that information with marketers. The two main methods for determining willingness to buy are observation of personal characteristics and consumer actions. As noted information about where a person lives (postal codes), how the person dresses, what kind of car he or she drives, occupation, income and spending patterns can be helpful in classifying consumers.

Monopoly and efficiency

According to the standard model,[citation needed] in which a monopolist sets a single price for all consumers, the monopolist will sell a lesser quantity of goods at a higher price than would companies by perfect competition. Because the monopolist ultimately forgoes transactions with consumers who value the product or service more than its cost, monopoly pricing creates a deadweight loss referring to potential gains that went neither to the monopolist nor to consumers. Given the presence of this deadweight loss, the combined surplus (or wealth) for the monopolist and consumers is necessarily less than the total surplus obtained by consumers by perfect competition. Where efficiency is defined by the total gains from trade, the monopoly setting is less efficient than perfect competition.

It is often argued that monopolies tend to become less efficient and less innovative over time, becoming "complacent", because they do not have to be efficient or innovative to compete in the marketplace. Sometimes this very loss of psychological efficiency can increase a potential competitor's value enough to overcome market entry barriers, or provide incentive for research and investment into new alternatives. The theory of contestable markets argues that in some circumstances (private) monopolies are forced to behave as if there were competition because of the risk of losing their monopoly to new entrants. This is likely to happen when a market's barriers to entry are low. It might also be because of the availability in the longer term of substitutes in other markets. For example, a canal monopoly, while worth a great deal during the late 18th century United Kingdom, was worth much less during the late 19th century because of the introduction of railways as a substitute.

Natural monopoly

A natural monopoly is a company which experiences increasing returns to scale over the relevant range of output and relatively high fixed costs.[71] A natural monopoly occurs where the average cost of production "declines throughout the relevant range of product demand". The relevant range of product demand is where the average cost curve is below the demand curve.[72] When this situation occurs it is always cheaper for one large company to supply the market than multiple smaller companies, in fact, absent government intervention in such markets will naturally evolve into a monopoly. An early market entrant which takes advantage of the cost structure and can expand rapidly can exclude smaller companies from entering and can drive or buy out other companies. A natural monopoly suffers from the same inefficiencies as any other monopoly. Left to its own devices a profit-seeking natural monopoly will produce where marginal revenue equals marginal costs. Regulation of natural monopolies is problematic.[citation needed] Fragmenting such monopolies is by definition inefficient. The most frequently used methods dealing with natural monopolies are government regulations and public ownership. Government regulation generally consists of regulatory commissions charged with the principal duty of setting prices.[73] To reduce prices and increase output regulators often use average cost pricing. By average cost pricing, the price and quantity are determined by the intersection of the average cost curve and the demand curve.[74] This pricing scheme eliminates any positive economic profits since price equals average cost. Average cost pricing is not perfect. Regulators must estimate average costs. Companies have a reduced incentive to lower costs. Regulation of this type has not been limited to natural monopolies.[74]

Government-granted monopoly

A government-granted monopoly (also called a "de jure monopoly") is a form of coercive monopoly by which a government grants exclusive privilege to a private individual or company to be the sole provider of a commodity; potential competitors are excluded from the market by law, regulation, or other mechanisms of government enforcement.[citation needed]

Monopolist shutdown rule

A monopolist should shut down when price is less than average variable cost for every output level.[75]-- in other words where the demand curve is entirely below the average variable cost curve.[75] Under these circumstances at the profit maximum level of output (MR = MC) average revenue would be less than average variable costs and the monopolists would be better off shutting down in the short term.[75]

Breaking up monopolies

When monopolies are not ended by the open market, sometimes a government will either regulate the monopoly, convert it into a publicly owned monopoly environment, or forcibly fragment it (see Antitrust law and trust busting). Public utilities, often being naturally efficient with only one operator and therefore less susceptible to efficient breakup, are often strongly regulated or publicly owned. American Telephone & Telegraph (AT&T) and Standard Oil are debatable examples of the breakup of a private monopoly by government: When AT&T, a monopoly previously protected by force of law, was broken up into various components in 1984, MCI, Sprint, and other companies were able to compete effectively in the long distance phone market.

Law

The existence of a very high market share does not always mean consumers are paying excessive prices since the threat of new entrants to the market can restrain a high-market-share company's price increases. Competition law does not make merely having a monopoly illegal, but rather abusing the power a monopoly may confer, for instance through exclusionary practices.

First it is necessary to determine whether a company is dominant, or whether it behaves "to an appreciable extent independently of its competitors, customers and ultimately of its consumer".[76] As with collusive conduct, market shares are determined with reference to the particular market in which the company and product in question is sold. The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) is sometimes used to assess how competitive an industry is.[77] In the US, the merger guidelines state that a post-merger HHI below 1000 is viewed as unconcentrated while HHI's above that provoke further review.[78]

By European Union law, very large market shares raise a presumption that a company is dominant,[79] which may be rebuttable.[80] If a company has a dominant position, then there is "a special responsibility not to allow its conduct to impair competition on the common market".[81] The lowest yet market share of a company considered "dominant" in the EU was 39.7%.[82]

Certain categories of abusive conduct are usually prohibited by a country's legislation.[83] The main recognised categories are:

- Limiting supply

- Predatory pricing

- Price discrimination

- Refusal to deal and exclusive dealing

- Tying (commerce) and product bundling

Despite wide agreement that the above constitute abusive practices, there is some debate about whether there needs to be a causal connection between the dominant position of a company and its actual abusive conduct. Furthermore, there has been some consideration of what happens when a company merely attempts to abuse its dominant position.

Historical monopolies

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2008) |

The term "monopoly" first appears in Aristotle's Politics, wherein Aristotle describes Thales of Miletus' cornering of the market in olive presses as a monopoly (μονοπωλίαν).[84][85]

Vending of common salt (sodium chloride) was historically a natural monopoly. Until recently, a combination of strong sunshine and low humidity or an extension of peat marshes was necessary for producing salt from the sea, the most plentiful source. Changing sea levels periodically caused salt "famines" and communities were forced to depend upon those who controlled the scarce inland mines and salt springs, which were often in hostile areas (e.g. the Sahara desert) requiring well-organised security for transport, storage, and distribution. The "Gabelle", a notoriously high tax levied upon salt, had a role in the beginning of the French Revolution, when strict legal controls specified who was allowed to sell and distribute salt.

Robin Gollan argues in The Coalminers of New South Wales that anti-competitive practices developed in the coal industry of Australia's Newcastle as a result of the business cycle. The monopoly was generated by formal meetings of the local management of coal companies agreeing to fix a minimum price for sale at dock. This collusion was known as "The Vend". The Vend ended and was reformed repeatedly during the late 19th century, ending by recession in the business cycle. "The Vend" was able to maintain its monopoly due to trade union assistance, and material advantages (primarily coal geography). During the early 20th century, as a result of comparable monopolistic practices in the Australian coastal shipping business, the Vend developed as an informal and illegal collusion between the steamship owners and the coal industry, eventually resulting in the High Court case Adelaide Steamship Co. Ltd v. R. & AG.[86]

Examples of monopolies

- The salt commission, a legal monopoly in China formed in 758.

- The British Honourable East India Company; created as a legal trading monopoly in 1600.

- Netherlands East India Company; created as a legal trading monopoly in 1602.

- Western Union was criticized as a "price gouging" monopoly in the late 19th century.[87]

- Standard Oil; broken up in 1911, two of its surviving "child" companies are ExxonMobil and the Chevron Corporation.

- U.S. Steel; anti-trust prosecution failed in 1911.

- Major League Baseball; survived U.S. anti-trust litigation in 1922, though its special status is still in dispute as of 2009.

- United Aircraft and Transport Corporation; aircraft manufacturer holding company forced to divest itself of airlines in 1934.

- National Football League; survived anti-trust lawsuit in the 1960s, convicted of being an illegal monopoly in the 1980s.

- American Telephone & Telegraph; telecommunications giant broken up in 1984.

- De Beers; settled charges of price fixing in the diamond trade in the 2000s.

- Microsoft; settled anti-trust litigation in the U.S. in 2001; fined by the European Commission in 2004 for 497 million euros.[88] which was upheld for the most part by the Court of First Instance of the European Communities in 2007. The fine was 1.35 Billion USD in 2008 for noncompliance with the 2004 rule.[89][90]

- Iarnród Éireann; The Irish Railway authority is a monopoly as Ireland does not have the size for more companies.

- Joint Commission; has a monopoly over whether or not US hospitals are able to participate with the Medicare and Medicaid programs.

- Telecom New Zealand; local loop unbundling enforced by central government.

- Deutsche Telekom; former state monopoly, still partially state owned, currently monopolizes high-speed VDSL broadband network.[91]

- Monsanto has been sued by competitors for anti-trust and monopolistic practices. They have between 70% and 100% of the commercial seed market.

- AAFES has a monopoly on retail sales at overseas military installations.

- State stores in certain United States states, e.g. for liquor.

- Long Island Power Authority (LIPA).

- Long Island Rail Road (LIRR).

Countering monopolies

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2010) |

According to professor Milton Friedman, laws against monopolies cause more harm than good, but unnecessary monopolies should be countered by removing tariffs and other regulation that upholds monopolies.

A monopoly can seldom be established within a country without overt and covert government assistance in the form of a tariff or some other device. It is close to impossible to do so on a world scale. The De Beers diamond monopoly is the only one we know of that appears to have succeeded. – In a world of free trade, international cartels would disappear even more quickly.[92]

However, professor Steve H. Hanke believes that although private monopolies are more efficient than public ones, often by a factor of two, sometimes private natural monopolies, such as local water distribution, should be regulated (not prohibited) by, e.g., price auctions.[93]

See also

- Bilateral monopoly

- Complementary monopoly

- Demonopolisation

- Duopoly

- Flag carrier

- History of monopoly

- Monopolistic competition

- Monopsony

- Oligopoly

- Ramsey problem, a policy rule concerning what price a monopolist should set.

- Simulations and games in economics education that model monopolistic markets.

Notes and references

- ^ Milton Friedman (2002). "VIII: Monopoly and the Social Responsibility of Business and Labor". Capitalism and Freedom (40th anniversary edition ed.). The University of Chicago Press. p. 208. ISBN 0-226-26421-1.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|edition=has extra text (help);|format=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Blinder, Alan S (2001). "11: Monopoly". Microeconomics: Principles and Policy. Thomson South-Western. p. 212. ISBN 0-324-22115-0.

A pure monopoly is an industry in which there is only one supplier of a product for which there are no close substitutes and in which is very difficult or impossible for another firm to coexist

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|format=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Binger, B & Hoffman, E.: Microeconomics with Calculus, 2nd ed. p 391 Addison-Wesley 1998.

- ^ Goodwin, Nelson, Ackerman, & Weissskopf, Microeconomics in Context 2d ed. (Sharpe 2009) at 307&08.

- ^ Samuelson & Marks, Managerial Economics 4th ed. (Wiley 2003) at 365-66.

- ^ a b c Nicholson & Snyder, Intermediate Microeconomics (Thomson 2007) at 379.

- ^ Frank (2009) 274.

- ^ Samuelson & Marks, Managerial Economics 4th ed. (Wiley 2003) at 365.

- ^ Goodwin, Nelson, Ackerman, & Weissskopf, Microeconomics in Context 2d ed. (Sharpe 2009) at 307.

- ^ Ayers & Collinge, Microeconomics (Pearson 2003) at 238.

- ^ Pindyck, R & Rubinfeld, D (2001) p. 127.

- ^ Png, I: Managerial Economics p. 271 Blackwell 1999 ISBN 1-55786-927-8

- ^ Png, I: Managerial Economics p. 268 Blackwell 1999 ISBN 1-55786-927-8

- ^ Negbennebor, A: Microeconomics, The Freedom to Choose CAT 2001

- ^ Mankiw, (2007) 338.

- ^ a b Hirschey, M, Managerial Economics. p. 426 Dreyden 2000.

- ^ Pindyck, R & Rubinfeld, D: Microeconomics 5th ed. p. 333 Prentice-Hall 2001.

- ^ Melvin and Boyes (2002) p.245.

- ^ Varian, H: Microeconomic Analysis 3rd ed. p. 235 Norton 1992.

- ^ Pindyck, R & Rubinfeld, D: Microeconomics 5th ed. p. 370 Prentice-Hall 2001.

- ^ Frank, (2008) p. 342.

- ^ Pindyck and Rubenfeld (2000) 325.

- ^ Nicholson (1998) p. 551.

- ^ Perfectly competitive firms are price takers. Price is exogenous and it is possible to associate each price with unique profit maximizing quantity. Besanko and Braeutigam, Microeconomics 2nd ed. (2005) p. 413.

- ^ a b Binger, B & Hoffman, E.: Microeconomics with Calculus, 2nd ed. Addison-Wesley 1998.

- ^ Frank (2009) 377.

- ^ a b Frank (2009) 377

- ^ Frank (2009) 378

- ^ Depken, Craig (November 23, 2005). "10". Microeconomics Demystified. McGraw Hill. p. 170. ISBN 0071459111.

- ^ The revolution in monopoly theory, by Glyn Davies and John Davies. Lloyds Bank Review, July 1984, no. 153, p. 38-52.

- ^ Levine, David (2008-09-07). Against intellectual monopoly. Cambridge University Press. p. 312. ISBN 978-0521879286.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Tirole, p.66.

- ^ Tirole, p. 66.

- ^ Tirole p. 65.

- ^ Hirschey, M, Managerial Economics. p. 412 Dreyden 2000.

- ^ Melvin & Boyes, Microeconomics 5th ed. (Houghton Mifflin 2002) 239

- ^ Pindyck, R & Rubinfeld, D: Microeconomics 5th ed. p.328 Prentice-Hall 2001

- ^ Varian, H.: Microeconomic Analysis 3rd ed. p. 233. Norton 1992.

- ^ Png, Managerial Economics (Blackwell 1999)

- ^ Krugman & Wells: Microeconomics 2d ed. Worth 2009

- ^ Goodwin, N, Nelson, J; Ackerman, F & Weissskopf, T p. 315.

- ^ Samuelson and Marks (2006) p. 104.

- ^ Samuelson and Marks (2006) p. 107.

- ^ a b Boyes and Melvin p.246.

- ^ Perloff (2008) p. 404.

- ^ Perloff, J.2009. p. 394.

- ^ Besanko, D. & Beautigam, R, (2005) p. 449.

- ^ Boyes and Melvin p. 246.

- ^ Wessels p. 159.

- ^ a b Boyes and Melvin p. 449.

- ^ Varian, H: 1992 p. 241.

- ^ Perloff, J. 2009 p. 393.

- ^ Boyes and Melvin page 449.

- ^ Perloff, J. 2009. p. 393.

- ^ Perloff, J. (200() p. 394.

- ^ Besanko, D. & Beautigam, R, 2005 p.448.

- ^ Hall, R and Liberman M. Microeconomics theory and Applications 2nd ed. South_Western (2001) p. 263.

- ^ Besanko, D. & Beautigam, R, 2005 p. 451

- ^ If the monopolist is able to segment the market perfectly, then the average revenue curve effectively becomes the marginal revenue curve for the company and the company maximizes profits by equating price and marginal costs. That is the company is behaving like a perfectly competitive company. The monopolist will continue to sell extra units as long as the extra revenue exceeds the marginal cost of production. The problem that the company has is that the company must charge a different price for each successive unit sold.

- ^ Varian, H: 1992 p. 242.

- ^ Perloff, J.(2009) p.396.

- ^ Besanko, D. & Beautigam, R, 2005 p. 449.

- ^ Because MC is the same in each market segment the profit maximizing condition becomes produce where MR1 = MR2 = MC. Pindyck and Rubinfeld p. 398-99.

- ^ As Pindyck and Rubinfeld note managers may find it easier to conceptualize the problem of what price to charge in each segment in terms of relative prices and price elasticities of demand. Marginal revenue can be written in terms of elasticities of demand as MR = P(1+1/PED). Equating MR1 and MR2 we have P1 (1+1/PED) = P2 (1+1/PED) or P1/P2 = (1+1/PED2)/(1+1/PED1). Using this equation the manager can obtain elasticity information and set prices for each segment. Pindyck and Rubinfeld (2009) pp. 401-02. Note that the manager may be able to obtain industry elasticities which are far more inelastic than the elasticity for an individual firm. As a rule of thumb the company’s elasticity coefficient is 5 to 6 times that of the industry. Pindyck and Rubinfeld (2009) pp. 402.

- ^ Colander, David C. p. 269.

- ^ Note that the discounts apply only to tickets not to concessions. The reason there is not any popcorn discount is that there is not any effective way to prevent resell. A profit maximizing theater owner maximizes concession sales by selling where marginal revenue equals marginal cost.

- ^ Lovell, (2004) p. 266.

- ^ Lovell (2004) p. 266.

- ^ Frank (2008) p. 394.

- ^ Frank (2008) p.266.

- ^ Binger, B & Hoffman, E.: Microeconomics with Calculus, 2nd ed. 406 Addison-Wesley 1998.

- ^ Samuelson, P. & Nordhaus, W.: Microeconomics, 17th ed. McGraw-Hill 2001

- ^ Samuelson, W & Marks, S: p. 376. Managerial Economics 4th ed. Wiley 2005

- ^ a b Samuelson, W & Marks, S: 100. Managerial Economics 4th ed. Wiley 2003

- ^ a b c Frank, R., Microeconomics and Behavior 7th ed. (Mc-Graw-Hill) ISBN 978-007-126349-8.

- ^ C-27/76 United Brands Continental BV v. Commission [1978] ECR 207

- ^ [www.univie.ac.at/RNIC/papers/kerber_kretschmer_vwangenheim.pdf Market Share Thresholds and Herfindahl-Hirschman-Index (HHI) as Screening Instruments in Competition Law: A Theoretical Analysis].

- ^ 1.5 Concentration and Market Shares. US Merger Guidelines.

- ^ C-85/76 Hoffmann-La Roche & Co AG v. Commission [1979] ECR 461

- ^ AKZO [1991]

- ^ Michelin [1983]

- ^ BA/Virgin [2000] OJ L30/1

- ^ Continental Can [1973]

- ^ Aristotle: Politics: Book 1

- ^ Aristotle, Politics

- ^ Robin Gollan, The Coalminers of New South Wales: a history of the union, 1860-1960, Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1963, 45-134.

- ^ Ars technica The Victorian Internet

- ^ EU competition policy and the consumer

- ^ Leo Cendrowicz (2008-02-27). "Microsoft Gets Mother Of All EU Fines". Forbes. Retrieved 2008-03-10.

- ^ "EU fines Microsoft record $1.3 billion". Time Warner. 2008-02-27. Retrieved 2008-03-10.

- ^ Kevin J. O'Brien, IHT.com, Regulators in Europe fight for independence, International Herald Tribune, November 9, 2008, Accessed November 14, 2008.

- ^ Milton Friedman, Free to Choose, p. 53-54

- ^ In Praise of Private Infrastructure, Globe Asia, April 2008

Further reading

- Guy Ankerl, Beyond Monopoly Capitalism and Monopoly Socialism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Schenkman Pbl., 1978. ISBN0870739387

- Impact of Antitrust Laws on American Professional Team Sports

External links

- Monopoly: A Brief Introduction by The Linux Information Project

- Monopoly by Elmer G. Wiens: Online Interactive Models of Monopoly (Public or Private) and Oligopoly

- Monopoly Profit and Loss by Fiona Maclachlan and Monopoly and Natural Monopoly by Seth J. Chandler, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

Beach, Chandler B., ed. (1914). The New Student's Reference Work. Chicago: F. E. Compton and Co.

Beach, Chandler B., ed. (1914). The New Student's Reference Work. Chicago: F. E. Compton and Co. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

Criticism

- Government and Microsoft: a Libertarian View on Monopolies (by François-René Rideau on his personal website)

- The Myth of Natural Monopoly (by Thomas J. DiLorenzo on www.Mises.org) - 1996

- Natural Monopoly and Its Regulation

- From rulers' monopolies to users' choices A critical survey of monopolistic practices

- Body of Knowledge on Infrastructure Regulation Monopoly and Market Power