Pancreas

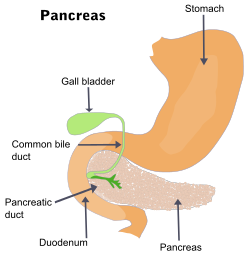

The pancreas /ˈpæŋkriəs/ is a gland organ in the digestive and endocrine system of vertebrates. It is both an endocrine gland producing several important hormones, including insulin, glucagon, and somatostatin, and a digestive organ, secreting pancreatic juice containing digestive enzymes that assist the absorption of nutrients and the digestion in the small intestine. These enzymes help to further break down the carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids in the chyme.

Histology

Under a microscope, stained sections of the pancreas reveal two different types of parenchymal tissue.[2] Lightly staining clusters of cells are called islets of Langerhans, which produce hormones that underlie the endocrine functions of the pancreas. Darker-staining cells form acini connected to ducts. Acinar cells belong to the exocrine pancreas and secrete digestive enzymes into the gut via a system of ducts.

| Structure | Appearance | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Islets of Langerhans | Lightly staining, large, spherical clusters | Hormone production and secretion (endocrine pancreas) |

| Pancreatic acini | Darker-staining, small, berry-like clusters | Digestive enzyme production and secretion (exocrine pancreas) |

Function

The pancreas is a dual-function gland, having features of both endocrine and exocrine glands.

The part of the pancreas with endocrine function is made up of approximately a million[3] cell clusters called islets of Langerhans. Four main cell types exist in the islets. They are relatively difficult to distinguish using standard staining techniques, but they can be classified by their secretion: α cells secrete glucagon (increase glucose in blood), β cells secrete insulin (decrease glucose in blood), δ cells secrete somatostatin (regulates/stops α and β cells), and PP cells secrete pancreatic polypeptide.[4]

The islets are a compact collection of endocrine cells arranged in clusters and cords and are crisscrossed by a dense network of capillaries. The capillaries of the islets are lined by layers of endocrine cells in direct contact with vessels, and most endocrine cells are in direct contact with blood vessels, either by cytoplasmic processes or by direct apposition. According to the volume The Body, by Alan E. Nourse,[5] the islets are "busily manufacturing their hormone and generally disregarding the pancreatic cells all around them, as though they were located in some completely different part of the body." The islet of Langerhans plays an imperative role in glucose metabolism and regulation of blood glucose concentration.

The pancreas as an exocrine gland helps out the digestive system. It secretes pancreatic fluid that contains digestive enzymes that pass to the small intestine. These enzymes help to further break down the carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids (fats) in the chyme.

In humans, the secretory activity of the pancreas is regulated directly via the effect of hormones in the blood on the islets of Langerhans and indirectly through the effect of the autonomic nervous system on the blood flow.[6]

- Sympathetic (adrenergic)

- α2: decreases secretion from beta cells, increases secretion from alpha cells, β2: increases secretion from beta cells

- Parasympathetic (muscarinic)

- M3: increases stimulation of alpha cells and beta cells[7]

Anatomy

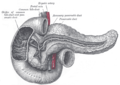

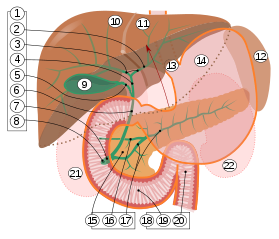

2. Intrahepatic bile ducts

3. Left and right hepatic ducts

4. Common hepatic duct

5. Cystic duct

6. Common bile duct

7. Ampulla of Vater

8. Major duodenal papilla

9. Gallbladder

10–11. Right and left lobes of liver

12. Spleen

13. Esophagus

14. Stomach

15. Pancreas:

16. Accessory pancreatic duct

17. Pancreatic duct

18. Small intestine:

19. Duodenum

20. Jejunum

21–22. Right and left kidneys

The front border of the liver has been lifted up (brown arrow).[8]

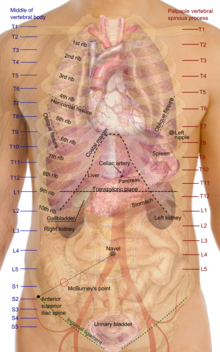

The pancreas lies in the epigastrium and left hypochondrium areas of the abdomen

It is composed of the following parts:

- The head lies within the concavity of the duodenum.

- The uncinate process emerges from the lower part of head, and lies deep to superior mesenteric vessels.

- The neck is the constricted part between the head and the body.

- The body lies behind the stomach.

- The tail is the left end of the pancreas. It lies in contact with the spleen and runs in the lienorenal ligament.

The superior pancreaticoduodenal artery from gastroduodenal artery and the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery from superior mesenteric artery run in the groove between the pancreas and the duodenum and supply the head of pancreas. The pancreatic branches of splenic artery also supply the neck, body and tail of the pancreas. The largest of those branches is called the arteria pancreatica magna; its occlusion, although rare, is fatal.

The body and neck of the pancreas drain into splenic vein; the head drains into the superior mesenteric and portal veins.

Lymph is drained via the splenic, celiac and superior mesenteric lymph nodes.

Diseases

Because the pancreas is a storage depot for digestive enzymes, injury to the pancreas is potentially very dangerous. A puncture of the pancreas generally requires prompt and experienced medical intervention.

Pancreatitis, inflammation of the pancreas. A variety of factors cause a high pressure within pancreatic ducts. Pancreatic duct rupture, and pancreatic juice leakage causes a pancreatic self-digestion. Therefore, pancreatitis occurs. Gallstone and alcohol are the two most common causes for the pancreatitis.

Pancreatic cancers, particularly cancer of the exocrine pancreas, remain one of the most deadly cancers, and the mortality rate is very high. Pancreatic endocrine tumors are rare. Representative: insulinoma (95% benign, 5% malignant), gastrinomas (malignant).

Diabetes mellitus type 1 is a chronic autoimmune disorder in which the immune system attacks the insulin-secreting cells in the pancreas. Secondary diabetes is a special type, which can be caused by many factors. There may be also some correlations between diabetes, chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer.

History

The pancreas was first identified for western civilization by Herophilus (335–280 BC), a Greek anatomist and surgeon. Only a few hundred years later, Rufus of Ephesus, another Greek anatomist, gave the pancreas its name. The term "pancreas" is derived from the Greek πᾶν ("all", "whole"), and κρέας ("flesh")[9] – it is presumed because of its fleshy consistency.

Embryological development

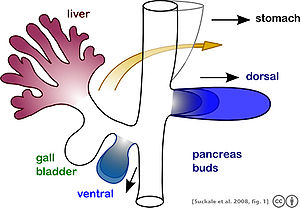

The pancreas forms from the embryonic foregut and is therefore of endodermal origin. Pancreatic development begins [with] the formation of a ventral and dorsal anlage (or buds). Each structure communicates with the foregut through a duct. The ventral pancreatic bud becomes the head and uncinate process, and comes from the hepatic diverticulum.

Differential rotation and fusion of the ventral and dorsal pancreatic buds results in the formation of the definitive pancreas.[10] As the duodenum rotates to the right, it carries with it the ventral pancreatic bud and common bile duct. Upon reaching its final destination, the ventral pancreatic bud fuses with the much larger dorsal pancreatic bud. At this point of fusion, the main ducts of the ventral and dorsal pancreatic buds fuse, forming the duct of Wirsung, the main pancreatic duct.

Differentiation of cells of the pancreas proceeds through two different pathways, corresponding to the dual endocrine and exocrine functions of the pancreas. In progenitor cells of the exocrine pancreas, important molecules that induce differentiation include follistatin, fibroblast growth factors, and activation of the Notch receptor system.[10] Development of the exocrine acini progresses through three successive stages. These include the predifferentiated, protodifferentiated, and differentiated stages, which correspond to undetectable, low, and high levels of digestive enzyme activity, respectively.

Progenitor cells of the endocrine pancreas arise from cells of the protodifferentiated stage of the exocrine pancreas.[10] Under the influence of neurogenin-3 and Isl-1, but in the absence of notch receptor signaling, these cells differentiate to form two lines of committed endocrine precursor cells. The first line, under the direction of Pax-0, forms α- and γ- cells, which produce glucagon and pancreatic polypeptides, respectively. The second line, influenced by Pax-6, produces β- and δ-cells, which secrete insulin and somatostatin, respectively.

Insulin and glucagon can be detected in the human fetal circulation by the fourth or fifth month of fetal development.[10]

In animals

Pancreatic tissue is present in all vertebrate species, but its precise form and arrangement vary widely. There may be up to three separate pancreases, two of which arise from ventral buds, and the other dorsally. In most species (including humans), these fuse in the adult, but there are several exceptions. Even when a single pancreas is present, two or three pancreatic ducts may persist, each draining separately into the duodenum (or equivalent part of the foregut). Birds, for example, typically have three such ducts.[11]

In teleosts, and a few other species (such as rabbits), there is no discrete pancreas at all, with pancreatic tissue being distributed diffusely across the mesentery and even within other nearby organs, such as the liver or spleen. In a few teleost species, the endocrine tissue has fused to form a distinct gland within the abdominal cavity, but otherwise it is distributed among the exocrine components. The most primitive arrangement, however, appears to be that of lampreys and lungfish, in which pancreatic tissue is found as a number of discrete nodules within the wall of the gut itself, with the exocrine portions being little different from other glandular structures of the intestine.[11]

Gallery

-

Accessory digestive system

-

Digestive organs

-

The celiac artery and its branches; the stomach has been raised and the peritoneum removed.

-

Lymphatics of stomach, etc., the stomach has been turned upward.

-

Transverse section through the middle of the first lumbar vertebra, showing the relations of the pancreas

-

The duodenum and pancreas

-

The pancreatic duct

-

Pancreas of a human embryo of five weeks

-

Pancreas of a human embryo at end of sixth week

-

Front of abdomen, showing surface markings for duodenum, pancreas, and kidneys

-

Dog pancreas magnified 100 times

-

Pancreas

-

Pancreas

-

Pancreas

-

Pancreas

References

- ^ Template:GeorgiaPhysiology

- ^ Histology image: 10404loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University

- ^ Hellman B, Gylfe E, Grapengiesser E, Dansk H, Salehi A (2007). "[Insulin oscillations--clinically important rhythm. Anti-diabetics should increase the pulsative component of the insulin release]". Lakartidningen (in Swedish). 104 (32–33): 2236–9. PMID 17822201.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ BRS physiology 4th edition ,page 255-256, Linda S. Constanzo, Lippincott publishing

- ^ The Body, by Alan E. Nourse, in the Time-Life Science Library Series (op. cit., p. 171.)

- ^ "New Research Redraws Pancreas Anatomy". 7 July 2011.

- ^ Verspohl EJ, Tacke R, Mutschler E, Lambrecht G (1990). "Muscarinic receptor subtypes in rat pancreatic islets: binding and functional studies". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 178 (3): 303–311. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(90)90109-J. PMID 2187704.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Standring S, Borley NR, eds. (2008). Gray's anatomy : the anatomical basis of clinical practice. Brown JL, Moore LA (40th ed.). London: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 1163, 1177, 1185–6. ISBN 978-0-8089-2371-8.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Pancreas". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2007-04-04.

- ^ a b c d Carlson, Bruce M. (2004). Human embryology and developmental biology. St. Louis: Mosby. pp. 372–4. ISBN 0-323-01487-9.

- ^ a b Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 357–359. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.