Cluster headache

| Cluster headache | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Frequency | 0.1% |

Cluster headache is a condition that involves, as its most prominent feature, an immense degree of pain (doctors and scientists consider it the most intense pain a human can endure without passing out, worse than burns, broken bones or child birth) that is almost always on only one side of the head.

Dr. Peter Goadsby, Professor of Clinical Neurology at University College London (now University of California, San Francisco), a leading researcher on the condition has commented:

"Cluster headache is probably the worst pain that humans experience. I know that’s quite a strong remark to make, but if you ask a cluster headache patient if they’ve had a worse experience, they’ll universally say they haven't. Women with cluster headache will tell you that an attack is worse than giving birth. So you can imagine that these people give birth without anesthetic [several] times a day.

Many cluster headache sufferers have committed suicide, leading to the nickname "suicide headaches" for cluster headaches.

Cluster headaches often occur periodically: spontaneous remissions interrupt active periods of pain, though there are about 20% of suffers whose cluster headaches never remit. The cause of the condition is currently unknown. It affects approximately 0.1% of the population, and men are more commonly affected than women."[1]

Signs and symptoms

Cluster headaches are excruciating unilateral headaches[2] of extreme intensity.[3] The duration of the common attack ranges from as short as 15 minutes to three hours or more. The onset of an attack is rapid, and most often without the preliminary signs that are characteristic of a migraine. However, some sufferers report preliminary sensations of pain in the general area of attack, often referred to as "shadows", that may warn them an attack is lurking or imminent. Though the headaches are almost exclusively unilateral, there are some documented as cases of "side-shifting" between cluster periods, or, even rarer, simultaneously (within the same cluster period) bilateral headache.[4] Trigeminal neuralgia can also bring on headaches with similar qualities. However, with trigeminal neuralgia the pain is mostly located around the facial area and is described as being like stabbing electric shocks, burning, pressing, crushing, exploding or shooting pain that becomes intractable.

Pain

The pain of cluster headaches is remarkably greater than in other headache conditions, including severe migraines; experts have suggested that it may be the most painful condition known to medical science. Female patients have reported it as being more severe than childbirth.[5] Dr. Peter Goadsby, Professor of Clinical Neurology at University College London (now University of California, San Francisco), a leading researcher on the condition has commented:

"Cluster headache is probably the worst pain that humans experience. I know that’s quite a strong remark to make, but if you ask a cluster headache patient if they’ve had a worse experience, they’ll universally say they haven't. Women with cluster headache will tell you that an attack is worse than giving birth. So you can imagine that these people give birth without anesthetic once or twice a day, for six, eight, or ten weeks at a time, and then have a break. It's just awful."[6]

The pain is lancinating or boring/drilling in quality, and is located behind the eye (periorbital) or in the temple, sometimes radiating to the neck or shoulder. Analogies frequently used to describe the pain are a red-hot poker inserted into the eye, or a spike penetrating from the top of the head, behind one eye, radiating down to the neck, or sometimes having a leg amputated without any anaesthetic. The condition was originally named Horton's Cephalalgia after Dr. B.T Horton, who postulated the first theory as to their pathogenesis. His original paper describes the severity of the headaches as being able to take normal men and force them to attempt or complete suicide. From Horton's 1939 paper on cluster headache:

"Our patients were disabled by the disorder and suffered from bouts of pain from two to twenty times a week. They had found no relief from the usual methods of treatment. Their pain was so severe that several of them had to be constantly watched for fear of suicide. Most of them were willing to submit to any operation which might bring relief."[7]

Thus, cluster headaches are also known by the nickname "suicide headaches".[8]

Other symptoms

The cardinal symptoms of the cluster headache attack are the severe or very severe unilateral orbital, supraorbital and/or temporal pain lasting 15–180 minutes, if untreated, and the attack frequency of one to 16 attacks in 48 hours. The headache is accompanied by at least one of the following autonomic symptoms: ptosis (drooping eyelid), miosis (pupil constriction) conjunctival injection (redness of the conjunctiva), lacrimation (tearing), rhinorrhea (runny nose), and, less commonly, facial blushing, swelling, or sweating, all appearing on the same side of the head as the pain.[9] The attack is also associated with restlessness, the sufferer often pacing the room or rocking back and forth. Less frequently, he or she will have an aversion to bright lights and loud noise during the attack. Nausea rarely accompanies a cluster headache, though it has been reported. The neck is often stiff or tender in the aftermath of a headache, with jaw or tooth pain sometimes present. Some sufferers report feeling as though their nose is stopped up and that they are unable to breathe out of one of their nostrils.

Secondary effects are inability to organize thoughts and plans, exhaustion and depression. Patients tend to dread facing another headache, and may adjust their physical activities or ask for help to accomplish normal tasks, and may hesitate to schedule plans in reaction to the clock-like regularity of the pain schedule leading to social isolation.

Recurrence

Cluster headaches are occasionally referred to as "alarm clock headaches" because of their ability to wake a person from sleep and because of the regularity of their timing: both the individual attacks and the clusters themselves can have a metronomic regularity; attacks striking at a precise time of day each morning or night is typical, even precisely at the same time a week later. The clusters tend to follow daylight saving time changes and happen more often around the spring and autumn equinox. This has prompted researchers to speculate an involvement of the brain's "biological clock" or circadian rhythm.

In episodic cluster headaches, these attacks occur once or more daily, often at the same times each day, for a period of several weeks, followed by a headache-free period lasting weeks, months, or years. Approximately 10–15% of cluster headache sufferers are chronic; they can experience multiple headaches every day for years.

Cluster headaches occurring in two or more cluster periods lasting from 7 to 365 days with a pain-free remission of one month or longer between the clusters are considered episodic. If the attacks occur for more than a year without a pain-free remission of at least one month, the condition is considered chronic.[10] Chronic clusters run continuously without any "remission" periods between cycles. Chronic sufferers may, however, have "high" and "low" cycles, meaning the frequency and intensity of attacks may change for a period of time, although the amount of change during these cycles varies between individuals and is not the same as the complete remission episodic sufferers experience. The condition may change from chronic to episodic and from episodic to chronic. Remission periods lasting for decades before the resumption of clusters have been known to occur.

Pathophysiology

Cluster headaches have been classified as vascular headaches. The intense pain is caused by the dilation of blood vessels which creates pressure on the trigeminal nerve. While this process is the immediate cause of the pain, the etiology (underlying cause or causes) is not fully understood.

Recently, researchers have linked low testosterone as a possible cause of cluster headaches.[11][12]

Hypothalamus

Among the most widely accepted theories is that cluster headaches are due to an abnormality in the hypothalamus; Dr Goadsby, an Australian specialist in the disease has developed this theory. This can explain why cluster headaches frequently strike around the same time each day, and during a particular season, since one of the functions the hypothalamus performs is regulation of the biological clock. Metabolic abnormalities have also been reported in patients.

The hypothalamus is responsive to light—daylength and photoperiod; olfactory stimuli, including sex steroids and corticosteroids; neurally transmitted information arising in particular from the heart, the stomach, and the reproductive system; autonomic inputs; blood-borne stimuli, including leptin, ghrelin, angiotensin, insulin, pituitary hormones, cytokines, blood plasma concentrations of glucose and osmolarity, etc.; and stress. These particular sensitivities may underlay the causes, triggers, and methods of treatment of cluster headache.

|

|

|

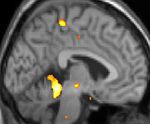

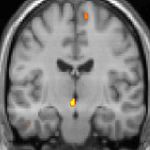

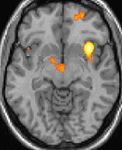

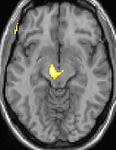

| Positron emission tomography (PET) shows brain areas being activated during pain | ||

|

|

|

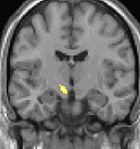

| Voxel-based morphometry (VBM) shows brain area structural differences | ||

The above positron emission tomography (PET) pictures indicate the brain areas which are activated during pain only, compared to the pain free periods. These pictures show brain areas which are always active during pain in yellow/orange colour (called "pain matrix"). The area in the centre (in all three views) is specifically activated during cluster headache only. The bottom row voxel-based morphometry (VBM) pictures show structural brain differences between cluster headache patients and people without headaches; only a portion of the hypothalamus is different.[13][14]

Genetics

There is a genetic component to cluster headaches, although no single gene has been identified as the cause. First-degree relatives of sufferers are more likely to have the condition than the population at large.[15]

Smoking

Tobacco consumption may trigger cluster headaches, and the affliction is often found in people with a heavy addiction to cigarette smoking. In some cases second hand smoke may trigger cluster headaches. However it is not clear if there is a causal relationship between smoking and cluster headaches. Some researchers think that people who suffer from cluster headaches may be predisposed to certain traits, including smoking or other lifestyle habits.[16]

Diagnosis

Cluster headaches often go undiagnosed for many years, being confused with migraine or other causes of headache.[17]

Many times a headache diary is useful- tracking when and where the pain occurs, how severe it is, how long the pain lasts, and coping strategies used will help a physician distinguish between the types of headaches.

Cluster headaches are benign, but because of the extreme and debilitating pain associated with them, and potential risk of suicide, a severe attack is nevertheless treated as a medical emergency. Because of the relative rareness of the condition and ambiguity of the symptoms, some sufferers may not receive treatment in the emergency room and people may even be mistaken as exhibiting drug-seeking behavior.

Differential

There are other types of headache that are sometimes mistaken for cluster headaches.

- Chronic paroxysmal hemicrania (CPH) is a condition similar to cluster headache, but CPH responds well to treatment with the anti-inflammatory drug indomethacin and the attacks are much shorter, often lasting only seconds.[18]

- Some people with extreme headaches of this nature (especially if they are not unilateral) may actually have an ictal headache. Anti-convulsant medications can significantly improve this condition so sufferers should consult a physician about this possibility.[19]

Prevention

A wide variety of prophylactic medicines are in use, and patient response to these is highly variable. Current European guidelines suggest the use of the calcium channel blocker verapamil at a dose of at least 240 mg daily. Steroids, such as prednisolone/prednisone, are also effective, with a high dose given for the first five days or longer (in some cases up to 6 months) before tapering down. Methysergide, lithium and the anticonvulsant topiramate are recommended as alternative treatments.[20] In Australia, neurologist John Watson has also reported success with sodium valproate and carbamazepine in some chronic, treatment-refractory cases.[citation needed]

Intravenous magnesium sulfate relieves cluster headaches in about 40% of patients with low serum ionized magnesium levels.[21] Melatonin has also been demonstrated to bring significant improvement in approximately half of episodic patients; psilocybin, dimethyltryptamine, LSD, and various other tryptamines have shown similar results.[22]

Management

Over-the-counter pain medications (such as aspirin, paracetamol, and ibuprofen) typically have no effect on the pain from a cluster headache. Unlike other headaches such as migraines and tension headaches, cluster headaches do not respond to biofeedback.[citation needed]

Medications to treat cluster headaches are classified as either abortives or prophylactics (preventatives). In addition, short-term transitional medications (such as steroids) may be used while prophylactic treatment is instituted and adjusted. With abortive treatments often only decreasing the duration of the headache and preventing it from reaching its peak rather than eliminating it entirely, preventive treatment is always indicated for cluster headaches, to be started at the first sign of a new cluster cycle.

Oxygen

During the onset of a cluster headache, many people respond to inhalation of 100% oxygen (12-15 litres per minute in a non-re-breathing mask). Some people have found better results with 25 litres per minute. There is also a study (commenced 2011) using an "on-demand" valve that can deliver up to 160 litres per minute.[23][20][24][25] When oxygen is used at the onset this can abort the attack in as little as 1 minute or as long as 10 minutes. Once an attack is at its peak, oxygen therapy appears to have little effect so many people keep an oxygen tank close at hand to use at the very first sign of an attack. An alternative first-line treatment is subcutaneous or intranasal administration of sumatriptan.[20] Hyperbaric oxygen therapy has been used successfully in treating cluster headaches though it was not shown to be more successful than surface oxygen.[26][27][28]

Triptans

Sumatriptan and zolmitriptan have both been shown to improve symptoms during an attack or indeed abort attacks.[29]

Other

Some non-narcotic treatments that have shown mixed levels of success are botox injections along the occipital nerve, as well as sarapin (pitcher plant extract) injections.[30][31]

Lithium, melatonin, valproic acid, topiramate as well as gabapentin are medications that can be tried as second line treatment options. Various surgical interventions have been tried in treatment-resistant cases but due to the invasiveness and limited evidence of effectiveness and uncertainty regarding adverse effects, surgery is not currently a recommended treatment.[32]

Lidocaine and other topical anesthetics sprayed into the nasal cavity may relieve or stop the pain,[33] normally in a few minutes, but long-term use is not suggested due to the side effects and possible damage to the nasal cavities. Ephedrine hydrochloride 1% nasal drops can relieve the painful swelling in the nasal passage and sinus on the affected side.

Previously, vaso-constrictors such as ergot compounds were also used, and sufferers report a similar relief by taking strong cups of coffee immediately at the onset of an attack. Cafergot, a cheap off-the-shelf vaso-constrictor, has been shown to stop cluster headaches within 40 minutes of ingestion. BOL (2-bromo lysergic acid diethylamide), a non-psychedelic form of the ergot-derived psychedelic LSD, has shown promise in the treatment of cluster headaches.[34] Case reports suggest that ingesting psilocybin or LSD can reduce cluster headache pain and interrupt cluster headache cycles, although this is controversial.[35]

Kudzu, a vine in the pea sub family, and sold as a herbal supplement, has shown promise as a treatment in the management of cluster headache. [2]

Epidemiology

While migraines are diagnosed more often in women, cluster headaches are more prevalent in men. The male-to-female ratio in cluster headache ranges from 4:1 to 7:1. It primarily occurs between the ages of 20 to 50 years.[36] This gap between the sexes has narrowed over the past few decades, and it is not clear whether cluster headaches are becoming more frequent in women, or whether they are merely being better diagnosed. Limited epidemiological studies have suggested prevalence rates of between 56 and 326 people per 100,000.[37]

History

The first complete description of cluster headache was given by the London neurologist Wilfred Harris in 1926. He named the disease Migrainous neuralgia.[38][39][40]

Cluster headaches have been called by several other names in the past including Erythroprosopalgia of Bing, Ciliary neuralgia, Erythromelagia of the head, Horton's headache (named after Bayard T. Horton, an American neurologist), Histaminic cephalalgia, Petrosal neuralgia, sphenopalatine neuralgia, Vidian neuralgia, Sluder's neuralgia, and Hemicrania angioparalyticia.[41] Sluder's neuralgia (syndrome) and cluster pain can often be temporarily stopped with nasal lidocaine drops.[42][43]

-

Robert Bing (1878–1956)

-

Bayard T. Horton (1895–1980)

See also

References

- ^ http://www.aafp.org/afp/2005/0215/p717.html

- ^ Beck E, Sieber WJ, Trejo R (2005). "Management of cluster headache". Am Fam Physician. 71 (4): 717–24. PMID 15742909.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Capobianco DJ, Dodick DW (2006). "Diagnosis and treatment of cluster headache". Semin Neurol. 26 (2): 242–59. doi:10.1055/s-2006-939925. PMID 16628535.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Meyer EL, Laurell K, Artto V, Bendtsen L, Linde M, Kallela M, Tronvik E, Zwart JA, Jensen RM, Hagen K (2009). "Lateralization in cluster headache: a Nordic multicenter study". J Headache Pain. 10 (4): 259–63. doi:10.1007/s10194-009-0129-z. PMID 19495933.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) PDF Comment Dr. Andrew Sewell - ^ Matharu M, Goadsby P (2001). "Cluster Headache -- Update on a Common Neurological Problem" (PDF). Practical Neurology. 1 (1): 42–9. doi:10.1046/j.1474-7766.2001.00505.x.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ http://www.abc.net.au/rn/talks/8.30/helthrpt/stories/s42434.htm

- ^ Horton BT, MacLean AR, Craig W.: A New Syndrome of Vascular Headache: Results of Treatment with Histamine. Proc Staff Meet, Mayo Clinic (1939) 14:257

- ^ "Cluster Headaches Can Make Life Unbearable". ABC News. 13 June 2001. Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- ^ IHS/ICHD-II 3.1 Cluster headache

- ^ IHS Classification ICHD-II 3.1.2 Chronic cluster headache

- ^ Stillman MJ (2006). "Testosterone replacement therapy for treatment refractory cluster headache". Headache. 46 (6): 925–33. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00436.x. PMID 16732838. Retrieved 24 August 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ceccarelli I, De Padova AM, Fiorenzani P, Massafra C, Aloisi AM (2006). "Single opioid administration modifies gonadal steroids in both the CNS and plasma of male rats". Neuroscience. 140 (3): 929–37. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.02.044. PMID 16580783. Retrieved 24 August 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ May A, Bahra A, Büchel C, Frackowiak RS, Goadsby PJ (2000). "PET and MRA findings in cluster headache and MRA in experimental pain". Neurology. 55 (9): 1328–35. PMID 11087776.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ DaSilva AF, Goadsby PJ, Borsook D (2007). "Cluster headache: a review of neuroimaging findings". Curr Pain Headache Rep. 11 (2): 131–6. doi:10.1007/s11916-007-0010-1. PMID 17367592.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pinessi L, Rainero I, Rivoiro C, Rubino E, Gallone S (2005). "Genetics of cluster headache: an update". J Headache Pain. 6 (4): 234–6. doi:10.1007/s10194-005-0194-x. PMID 16362673.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schürks M, Diener HC (2008). "Cluster headache and lifestyle habits". Curr Pain Headache Rep. 12 (2): 115–21. doi:10.1007/s11916-008-0022-5. PMID 18474191.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Vast Majority of Cluster Headache Patients Are Initially Misdiagnosed, Dutch Researchers Report". World Headache Alliance. 21 August 2003. Archived from the original on 25 September 2006. Retrieved 8 October 2006.

- ^ NEURO/67 at eMedicine

- ^ "Seizures and Headaches: They Don't Have to Go Together". Epilepsy.com. 16 September 2003. Retrieved 22 September 2006.

- ^ a b c May A, Leone M, Afra J, Linde M, Sándor P, Evers S, Goadsby P (2006). "EFNS guidelines on the treatment of cluster headache and other trigeminal-autonomic cephalalgias". Eur J Neurol. 13 (10): 1066–77. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01566.x. PMID 16987158.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Free Full Text (PDF) - ^ Mauskop, Alexander; Altura, Bella T.; Cracco, Roger Q.; Altura, Burton M. (1995). "Intravenous magnesium sulfate relieves cluster headaches in patients with low serum ionized magnesium levels". Headache. 35 (10): 597–600. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.1995.hed3510597.x. PMID 8550360.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - ^ Leone M; et al. (19965). "Melatonin versus placebo in the prophylaxis of cluster headache: a double-blind pilot study with parallel groups". Cephalalgia. 16 (7): 494–496. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.1996.1607494.x. PMID 8933994.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|year=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ [1]

- ^ Cohen AS, Burns B, Goadsby PJ (2009). "High-flow oxygen for treatment of cluster headache: a randomized trial". JAMA. 302 (22): 2451–7. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1855. PMID 19996400.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cohen AS, Burns B, Goadsby PJ (2009). "High-flow oxygen for treatment of cluster headache: a randomized trial". JAMA. 302 (22): 2451–7. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1855. PMID 19996400.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bennett MH, French C, Schnabel A, Wasiak J, Kranke P (2008). Bennett, Michael H (ed.). "Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD005219. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005219.pub2. PMID 18646121.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|chapter=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nilsson Remahl AI, Ansjön R, Lind F, Waldenlind E (2002). "Hyperbaric oxygen treatment of active cluster headache: a double-blind placebo-controlled cross-over study". Cephalalgia. 22 (9): 730–9. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.2002.00450.x. PMID 12421159. Retrieved 22 August 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Di Sabato F, Rocco M, Martelletti P, Giacovazzo M (1997). "Hyperbaric oxygen in chronic cluster headaches: influence on serotonergic pathways". Undersea Hyperb Med. 24 (2): 117–22. PMID 9171470. Retrieved 22 August 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Law S, Derry S, Moore RA (2010). Law, Simon (ed.). "Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4 (4): CD008042. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008042.pub2. PMID 20393964.

{{cite journal}}:|chapter=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sostak P, Krause P, Förderreuther S, Reinisch V, Straube A (2007). "Botulinum toxin type-A therapy in cluster headache: an open study". J Headache Pain. 8 (4): 236–41. doi:10.1007/s10194-007-0400-0. PMID 17901920.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Interview with Dr. Jeff Baird: Treating Migraines with Medical Acupuncture". American Academy of Medical Acupuncture. Retrieved 24 August 2008.

- ^ Chen PK, Chen HM, Chen WH; et al. (2011). "[Treatment guidelines for acute and preventive treatment of cluster headache]". Acta Neurol Taiwan (in Chinese). 20 (3): 213–27. PMID ((Depakote)) 22009127 ((Depakote)).

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmid=value (help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mills T, Scoggin J (1997). "Intranasal lidocaine for migraine and cluster headaches". Ann Pharmacother. 31 (7–8): 914–5. PMID 9220056.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ The Treatment of Cluster Headaches Using 2-Bromo-Lysergic Acid Diethylamide. The Beckley Foundation

- ^ Sun-Edelstein C, Mauskop A. (2011). "Alternative headache treatments: nutraceuticals, behavioral and physical treatments". Headache: the Journal of Head and Face Pain. 51 (3): 469–83. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01846.x. PMID 21352222.

- ^ http://www.diamondheadache.com/article_archives/cluster_headache.html

- ^ Torelli P, Castellini P, Cucurachi L, Devetak M, Lambru G, Manzoni G (2006). "Cluster headache prevalence: methodological considerations. A review of the literature". Acta Biomed Ateneo Parmense. 77 (1): 4–9. PMID 16856701.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Harris W.: Neuritis and Neuralgia. Oxford: Oxford Univ.Press; 1926

- ^ Bickerstaff ER (1959). "The periodic migrainous neuralgia of Wilfred Harris". Lancet. 1 (7082): 1069–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(59)90651-8. PMID 13655672.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Boes CJ, Capobianco DJ, Matharu MS, Goadsby PJ (2002). "Wilfred Harris' early description of cluster headache". Cephalalgia. 22 (4): 320–6. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.2002.00360.x. PMID 12100097.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stephen D. Silberstein, Richard B. Lipton. Peter J. Goadsgy. "Headache in Clinical Practice." Second edition. Taylor & Francis. 2002.

- ^ Kittrelle JP, Grouse DS, Seybold ME (1985). "Cluster headache. Local anesthetic abortive agents". Arch. Neurol. 42 (5): 496–8. PMID 3994568.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Costa A, Pucci E, Antonaci F; et al. (2000). "The effect of intranasal cocaine and lidocaine on nitroglycerin-induced attacks in cluster headache". Cephalalgia. 20 (2): 85–91. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.2000.00026.x. PMID 10961763.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- ClusterHeadacheInfo.org - Cluster Headache Information, Discussion, Support

- - Cluster Headache Information and Support on facebook

- Clusterheadaches.com.au - worldwide cluster headache information & support group

- Clusterheadaches.com, worldwide cluster headache support group

- Algorithm for diagnosis and treatment from National Guideline Clearinghouse (DHHS)

- The International Headache Society (IHS): 2nd Edition of The International Headache Classification (ICHD-2) - 3.1 Cluster Headache

- Organisation for the Understanding of Cluster Headache (UK)

- Association Française Contre l'Algie Vasculaire de la Face (FR)

- European ClusterHeads Alliance

- The City of London Migraine Clinic video on Cluster Headache

- The City of London Migraine Clinic video on Suicide Headache

- Video of a cluster headache attack

- Eurolight: A European initiative to evaluate the impact of Cluster Headache