Warez

Warez (pronounced like the word wares [weə(r)z] or similarly to the English pronunciation of Juárez [warɛs], though this is actually ['xwaɾes] in Spanish) is a derivative of the plural form of "software". It refers primarily to copyrighted material traded in violation of its copyright license. The term generally refers to releases by organized groups, as opposed to peer-to-peer file sharing between friends or large groups of people with similar interest using a Darknet. It usually does not refer to commercial for-profit software counterfeiting. This term was initially coined by members of the various computer underground circles, but has since become commonplace among Internet users and the media.

Prior to the 1990s, pirated software was simply known as "wares". The rise of "l33t sp34k" (leet speak or elite speech) lent to the substitution of the "z" for the "s". "Warez" was used to indicate more than one pirated software application, as the plural of "software" is "software" and it lacks clarity when referring to more than one "ware". Due to the low rate of speed in transferring pirated software over telephone modems and bulletin board systems (BBSes), pirates would typically ask for one for one trades from other pirates. Hence, software pirates adopted a merchant-like attitude with their software collections and the term "wares" was apt.

"Warez" is used most commonly as a noun: "My neighbor downloaded 10 gigs of warez yesterday"; but can also be used as a verb: "The new Windows was warezed a month before the company officially released it". The collection of warez groups is referred to globally as the "warez scene" or more ambiguously "The Scene".

Terminology

All words have shades of meaning, some denotative, others connotative, some implying social acceptability, others pejorative. Whoever controls access to the discourse is able to pick the words with meanings that frame the reader's response. While the term 'piracy' is commonly used to describe a significant range of activities, most of which are unlawful, the relatively neutral meaning in this context is "...mak[ing] use of or reproduc[ing] the work of another without authorization" [1]. Some groups (including the Free Software Foundation) object to the use of this and other words such as "theft" because they represent a partisan attempt to create a prejudice that is used to gain political ground. "Publishers often refer to prohibited copying as "piracy." In this way, they imply that illegal copying is ethically equivalent to attacking ships on the high seas, kidnapping and murdering the people on them" (FSF). The FSF advocate the use of terms like "prohibited copying" or "unauthorized copying", or "sharing information with your neighbor."

On the other hand, many self-proclaimed "software pirates" take pride in the term, thinking of the romanticized Hollywood portrayal of pirates and sometimes jokingly using "pirate talk" in their conversations. Although the use of this term is controversial, it is embraced by some groups such as Pirates With Attitude.

The term 'piracy' as used in this article reflects its widespread adoption, and does not imply endorsement of one point of view.

History of warez

Product piracy

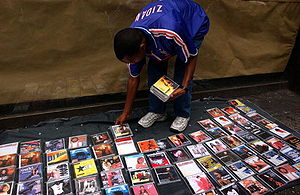

Before there were computers and software, piracy existed; At the time, piracy was usually, though not always, profit-oriented. These groups illegally produce millions of counterfeit copies of clothing, electronics, microchips, music CDs, VHS & DVD movies, and software applications.

While most copies of pirate software are manufactured in Asian factories, their distribution often begins in first-world nations such as the United States and Western Europe, where the largest international publishers of proprietary software are located. These pirate copies are regularly sold on city streets throughout most of South America, Asia, the Middle East and Eastern Europe. In some countries they are sold at retail price which can be worth several billion dollars annually. The selling of pirated copies is a seldom mentioned issue in Western nations especially in US and UK which might indicate a more sophisticated operation.

Rise of software piracy

Software piracy has been an issue from the day the first commercial software program hit store shelves. Whether the medium was cassette tape or floppy disk, software pirates found a way to duplicate the software and spread it amongst their friends. Thriving pirate communities were built around the Apple II, Commodore 64, the Atari 400 and Atari 800 line, the ZX Spectrum, the Amiga, the Atari ST among other personal computers. Entire networks of BBSes sprung up to traffic illegal software from one user to the next. Machines like the Amiga and the Commodore 64 had an international pirate network; software not available on one continent would eventually make its way to every region through the pirate network via the bulletin board systems.

It was also quite common in the 1980's to use physical floppy disks and the postal service for spreading software, in an activity known as mail trading. Particularly widespread in the continental Europe, mail trading was even used by many of the leading cracker groups as their primary channel of interaction. Software piracy via mail trading was also the most relevant means for many computer hobbyists in the Eastern bloc countries to receive new Western software for their computers.

Copy protection schemes for the early systems were designed to defeat the casual pirate, as "crackers" would typically release a pirated game to the pirate "community" the day they were earmarked for market.

However, until the early 1990s, software piracy was not yet considered a serious problem. In 1992, the Software Publishers Association began to battle against software piracy, with its promotional video "Don't Copy That Floppy". It and the Business Software Alliance have remained the most active anti-piracy organizations worldwide, although to compensate for extensive growth in recent years, they have gained the assistance of the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), as well as American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP) and Broadcast Music Incorporated (BMI).

These are some causes which have accelerated its growth:

Popularity of computers

In the late 1990s, computers became more popular. This was attributed to Microsoft and the release of Windows 95, which greatly decreased the learning curve for using a computer. Windows 95 became so popular that in developed countries nearly every middle-class household has at least one computer. Similar to televisions and telephones, computers became a necessity to every person in the information age. As the use of computers increased, so had software and cyber crimes. The problem of warez became so serious that it had adversely affected software writers and companies.

Improvements in networking

In the mid-1990s, the average Internet user was still on dial-up, with average speed ranging between 28.8 and 33.6 kbit/s (with a maximum speed of 56 kbit/s). If one wished to download a piece of software, which could run about 20 MB, the download time could be longer than one day, depending on network traffic, the Internet Service Provider, and the server. Around 1997, broadband began to gain popularity due to its greatly increased network speeds. As "large-sized file transfer" problems became less severe, warez became more widespread and began to affect large software files like animations and movies. The next generation of networking is optical fiber network, whose speed can reach up to 1.6 Tb/s in field deployed systems and up to 10 Tb/s in lab systems, with this seemingly unlimited bandwidth it is virtually impossible to imagine a limit as to what could be pirated.

Invention of swarming download technology

In the past, files were distributed by point-to-point technology: with a central uploader distributing files to downloaders. With these systems, a large number of downloaders for a popular file uses an increasingly larger amount of bandwidth. If there are too many downloads, the server can become unavailable. The same is true for peer-to-peer networking; the more downloaders the slower the file distribution is. With swarming technology as implemented in eDonkey2000 and BitTorrent file sharing systems, downloaders help the uploader by picking up some of its uploading responsibilities. When one downloads files, one is not only a downloader, but also an uploader. To a point, the more downloaders there are, the faster the file distribution becomes.

Types of warez

There is generally a distinction made between different sub-types of warez:

- appz – Applications: Generally a retail version of a software package.

- crackz – Cracked applications: A modified executable or more (usually one) and/or a library (usually one) or more and/or a patch designed to turn a trial version of a software package into the full version and/or bypass anti-piracy protections.

- gamez – Games: This scene concentrates on both computer based games, and video game consoles, though the latter are more often referred to as ISOs and ROMs.

- moviez – Movies: Pirated movies generally released while still in theaters or from DVDs prior to the actual retail date.

- tvrip – Televisions: Television shows generally released within minutes after airing, with all commercials edited out. DVD Rips of television series fall under this sub-type.

- mp3z – MP3 audio: Pirated albums, singles, or other audio format released in the compressed MP3 audio format.

- bookz/ebookz/e-bookz – Books: These can include pirated ebooks, scanned books, scanned comics and manga.

Software piracy

Software cracking groups delegate tasks efficiently among their members. These members are mostly located in first world countries where high-speed internet connections and powerful computers are readily available. Software cracking groups are usually quite small. Only a few skilled people usually do the cracking work, since the programming skills required to reverse engineer and patch code usually takes years of training and talent.

Effect of piracy on "free" and "open source" software

Piracy can also affect free and open source software. Since it is hard to monitor the distribution of software, malicious individuals and groups can take their software away with different illicit uses:

Credit Theft

People simply take the free software away and claim it is their work. If it is open source software, it is even easier for them to remove any tracks which can identify the original author(s). They then add their own names and/or logos so as to pretend the work is their own.[2]

Repackaging and Resale

In order to make a profit out of freeware, they resell their products after stealing works from the original software authors. An example is the Kuwaiti company OnlinePcFix, which offers a software named SpyFerret. This software's internal database was later revealed to have been stolen from the complete database of Spybot - Search & Destroy. To hide the fact that the company stole Spybot's database, they make use of encryption.[3]

Modification and Resale

It has occurred most with "open source" software, where the source code is freely available and modified. An example of this was CherryOS. Its authors took the source code from PearPC and sold it as their own creation. Although the group was later discovered to have copied source code, they still have not publicly acknowledged the theft. This act is against the principles of the GNU General Public License, under which PearPC was released.

Movie piracy

Movie piracy was looked upon as impossible by the major studios. When dial-up was common in early and mid 1990s, movies distributed on the Internet tended to be small. The techniques that were usually used to make them small were to use compression software and lower the video quality. At that time, the largest piracy threat was software.

However, along with the rise in broadband internet connections beginning around 1998, higher quality movies began to see widespread distribution – ISO images copied directly from the original DVDs were slowly becoming a feasible distribution method. Today, movie piracy has become so common that it has caused major concern amongst movie studios and their representative organizations. Because of this the MPAA is often running campaigns during movie trailers where it tries to discourage young people from copying material without permission. Unlike the music industry, which has online music stores supported by music programs such as iTunes, the movie industry is still currently lacking an alternative against the illegal distribution.

Different release types

The first and most well-known form of pirated movies is known as a "Cam" recording. These rips were the first attempts at movie piracy, but as these recordings often have low quality, alternative methods were sought. Beginning in 1998, feature films began to be released on the internet by warez groups prior to their theatrical release. These pirated versions came usually in the form of VCD or SVCD.

A prime example was the EViL release of American Pie.[4] This is notable for three reasons:

- It was released in uncensored workprint format. The later theatrical release was cut down by several minutes and had scenes reworked to avoid nudity to pass MPAA guidelines.

- It was released nearly two months prior to its release in theaters (CNN Headline News reported on its early release).

- It was listed by the movie company as one of the reasons it released an Unrated DVD edition.

In October 1999 DeCSS was released, this program allowed anyone to remove the CSS encryption on a DVD. Though its authors claimed that this software was meant only for playback purposes, it also meant that one could copy the content perfectly; combined with the "DivX ;-) 3.11 Alpha" codec released shortly after, the new codec increased video quality from near VHS to almost DVD quality when encoding from a DVD source. The early DivX releases were mostly internal for group use, but once the codec spread, it became accepted as a standard. It quickly became the format for scene. With help from associates who either work for a movie theater, movie production company, or video rental company, groups were supplied with massive amounts of material, and new releases began appearing at a very fast pace. When a new release of DivX came out (Version 4.0), the codec went commercial, and the need for a free codec XviD emerged. Today, XviD has replaced DivX almost entirely, DivX isn't even allowed as a format for scene releases anymore. Although DivX codec has evolved from version 4 to 6 during this time, it is considered obsolete due the commercial nature of the codec.

Here is a table of movie ripping methods and sources, ranging from the lowest quality to the highest. Some sample images are provided for visual comparison.

Note: Screeners make a small exception here, since the content may differ from a retail version, it can be considered as lower quality than a DVD-Rip (even if the screener in question was sourced from a DVD).

| Type | Label | Rarity | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cam | "CAM" | Very Common | A Night at the Roxbury |

| A copy made in a cinema using a camcorder, possibly mounted on a tripod. Sound source is the camera microphone. Cam rips can appear online fast, after first preview, or premiere of the film, but the quality is always quite horrible. | |||

| Telesync | "TS" "TELESYNC" |

Common | Chicken Little |

| A copy made in a cinema using a camcorder mounted on a tripod for a more steady shot. Synchronized with a secondary audio recording, either done with a professional microphone in an empty cinema, fed directly from the cinema's sound system, or captured from an FM radio transmission intended for hearing-impaired customers. Often, a "Cam" is mislabeled as a telesync. Telesync usually has certain angle in the image, because the camera is below and possibly off from the center of the screen. | |||

| Telecine | "TC" "TELECINE" |

Uncommon | Æon Flux |

| A copy captured from a film print using a machine that transfers the movie from its analog reel to digital format. These were rare because the telecine machine for making these prints is very costly and very large, however, recently they have become much more common. Telecine is basically same quality as DVD, since the technique is same as digitizing the actual film to DVD, but the result is inferior, since the source material is usually lower quality copy reel. Telecine machines usually cause a slight left-right jitter in the picture, and the color levels are inferior compared to DVD. Note the piece of lint in frame above; this is a common occurrence during digital film transfer, particularly when not done in a clean room environment. | |||

| Workprint | "WP" "WORKPRINT" |

Rare | American Pie |

| A copy made from an unfinished version of a film produced by the studio. Typically a workprint is missing effects overlays, and may not be identical to its theatrical release. Some workprints have a time index marker running in a corner or on the top edge; some may also include a watermark. Workprint might be uncut version, and missing some material that would appear in the final movie. Note the index timer below the frame in the image. | |||

| Screener | "SCR" "SCREENER" "DVDSCR" "DVD-SCREENER" "VHS-SCREENER" |

Common | She's All That |

| These are early DVD or VHS releases of the theatrical version of a film, typically sent to movie reviewers, Academy members, and executives for review purposes. A screener normally has a message overlaid on its picture, with wording similar to: "The film you are watching is a promotional copy, if you purchased this film at a retail store please contact 1-800-NO-COPIES to report it." Apart from this, some movie studios release their screeners with a number of scenes of varying duration shown in black-and-white. Aside from this message, and the occasional B&W scenes, screeners are normally of only slightly lower quality than a retail DVD-Rip, due to the smaller investment in DVD mastering for the limited run. | |||

| DVD Rip | "DVD-Rip" | Very Common | Shogun TV Miniseries |

| A final retail version of a film, typically released before it is available outside its originating region. Often after one "release group" releases a high-quality DVD-Rip, the "race" to release that film will stop. Because of their high quality, DVD-Rips generally replace any earlier copies that may already have been circulating. | |||

| DVDR | "DVDR image" | Very Common | |

| A final retail version of a film in DVD format. Usually complete copy from the original DVD. If the original DVD is released in DVD-9 format, extras might have been removed and/or video re-encoded to make the image fit the more common and less expensive (for burning) DVD-5 format. DVDR releases often follow DVD-Rips after a few hours. | |||

| HDTV or DS Rip | "DSR" "DSRip" "DVB" "HDTV" |

Common | Lost from DVB quality rip Starship Troopers from HDTV High Resolution rip |

| Digital stream rip is a rip that is captured from a digital source stream, such as a HDTV or DVB transmission. With HDTV source, the quality can sometimes even surpass DVD. Movies in this format are rare, as this source is used for primarily for TV show ripping. | |||

Distribution of warez

Organized groups operate with strict rule set of what can be released and in which format each release should be. The groups may also have private sites for internal purposes, such as archiving their own releases and transferring the unmodified material between their members. Communication within a group is usually handled through encrypted channels (with Blowfish, AES, or some other cipher & key method), using SSL secured private Internet Relay Chat (IRC) servers. Communication within a group is important in coordinating their releases. Groups usually focus on some specific area of expertise and release material from their field. These groups usually transfer material using between topsites.

Disorganized distribution usually consists of average computer users, who are using some form of p2p to transfer material. These users often rely on Usenet binaries newsgroups, BitTorrent or IRC XDCC bots to distribute their material. These new releases typically don't spread far, but since there's no real way to track what was released and where, this is hard to do. Disorganized groups rarely release software, since releasing usually requires a competent programmer to patch the original program. Usually these types of releases are MP3, cloned game images and movies.

Distribution methods

There are several methods warez creators can distribute their material. The methods include, but are not limited to: File Transfer Protocol (FTP), File eXchange Protocol (FXP), Peer-to-peer (P2P), and Usenet And not forgetting XDCC or Xabi Direct Client Connection.

The typical warez scene release process is as follows:

- A popular new piece of commercial software is released by the software company.

- A warez group might use one of its contacts to obtain a pre-release copy, steal it from a DVD/CD pressing plant, or obtain it from a retail store before release date or once it has been released.

- It is then sent to a skilled software cracker/programmer to remove copy prevention.

- It is packed in proper format (usually split and compressed using the RAR file format), and it is uploaded to private FTP servers which act as a group's archive.

- The packs are uploaded to topsites, and once they are complete on all the sites, the group PREs.

- It is then moved by couriers to many smaller and possibly slower FTP servers around the world.

Steps 4, 5, and 6 can be used to describe all types of Warez, since the distribution format is defined in standards.

Many, if not all, release groups claim to look down on peer-to-peer networks and protest against users making their warez available on such networks.

File formats of warez

- For more specific information see Standard (warez)

The modern warez scene deals with petabytes of data and thus the need for an efficient system of handling files was apparent. A typical CD software release can contain up to 700 megabytes of data, which presents challenges when sending over the Internet. This was especially true in the early days when everything was done via dial-up connections. These challenges apply to an even greater extent for a single-layer DVD release, which can contain up to 4.7 GB of data. The warez scene made it standard practice to split releases up into many separate pieces, called disks, using several file compression formats: (historical LZH, ACE, ARJ), ZIP, RAR and most commonly TAR.

This method has many advantages over sending a single large file:

- The two-layer compression could sometimes achieve almost a tenfold improvement over the original DVD/CD image. The overall file size is cut down and lessens the transfer time and bandwidth required.

- If there is a problem during the file transfer and data was corrupted, it is only necessary to resend the few corrupted RAR files instead of resending the entire large file.

- This method also creates the facility of downloading from many sources.

File verification is accomplished using SFV files, which is usually integrated into the topsites FTP server software so that files are verified automatically as they are uploaded. Ironically, the distribution methods used by the warez scene are so efficient that they are sometimes superior to the ones used by actual software producers.

Releases of software titles often come in two forms. The full form is a full version of game or application, generally released as CD or DVD-writable disk images (BIN or ISO files). A rip is a cut-down version of the title in which important additions included on the legitimate DVD/CD (generally Portable Document Format (PDF) manuals, help files, tutorials, and sample media) is omitted. In a game rip, generally all game video is removed, and the audio is compressed to MP3 or Vorbis, which must then be decoded to its original form before playing.

Motivations and arguments

Pirates generally exploit the international nature of the copyright issue to avoid law enforcement in specific countries. In Russia, the copying of software was once explicitly permitted by law when such software was not in the Russian language. This is no longer the case, but prosecutions for copyright infringement are still very rare.

The production and/or distribution of warez is illegal in most countries. However, it is typically overlooked in poorer third world countries with weak or non-existent IP protection. Some first world countries have loopholes in legislation that allow the warez scene to operate almost legally as compared to P2P-distribution, since it can be proven that shared material was targeted to a limited group.

Pro-warez argument

The morality of copyright infringement is also disputed, with members of warez groups often viewing their actions as "socially positive". The following are their justifications:

- Difficulty of implementing copyright enforcement – Warez groups believe that they are allowed to continue their activities due to the nature of Internet globalization, inconsistent worldwide laws and technical difficulties in tracking warez groups.

- Difference between copyright infringement and conventional property theft – Copying software is different from theft or stealing other people's property, namely, it does not deprive the use of the software from the original owner.

- Criticism of copyright laws – Some warez groups may regard copyright as harmful to society. For example, it hinders creation and over-protects the rights of copyright holders. Sometimes the protection is even ridiculous or unnecessary. For instance, it is ridiculous to regard "a legitimate backup copy of a purchased CD" or "a format transfer of music (eg. from *.wav to *.mp3)" as illegal in some countries.

- Criticism of copyright holders – There are various reasons, including: some warez groups may hate copyright holders or their companies. They distribute software as a form of revenge possibly because they have had bad experiences with the software company(s). The copyright holder is unjust or greedy in that it exploits its own staff.

- Philosophy of freebies – All software should be distributed free of charge. Reasons include: the effect/cost of creating software is just one-off. It is wrong to charge every copy of the software.

- High price – Since copyright holders sell their products and services at a unacceptably high prices, users should not pay for these companies or holders.

- Perceived injustice of the poor – This point is similar to the above reasons. Warez groups feel it is bad not to share products and services with those who could not afford to obtain it otherwise. These groups compare themselves to Robin Hood.

- Full trial before buy – Some software owners only give function-limited demo or do not give demo at all. Users need to fully trial them before deciding whether to buy it or not.

- Deprivation of individual rights – Laws such as the Digital Millennium Copyright Act may also contribute to the motivations of those involved in warez, as user rights are increasingly threatened in the United States and rights holders attempt to lock out consumers.

- Increase market share – Companies such as Adobe, Borland, and Microsoft have gained big market shares due to vast numbers of warez users, such as college students and working people who adopted applications as they were readily available. Later when they find out that the software is useful, these people purchase legitimate licenses for future uses. This helps companies with software familiarity and dominancy.

- Victimless crime – If the warez user truly never would have purchased the product, it is argued that the copyright holder does not incur a loss.

Anti-warez arguments

People opposed to warez typically argue that the motivating factors given by cracking groups are not authentic:

- High price is not an excuse to piracy – The argument of "unreasonable price" or "could not afford the price" is not an excuse to ignore the law. The analogy is of taking goods away from a shop if the prices are too high. For that argument, if one believes that the prices are too high, the person is advised to visit other shops or to not buy the goods in question.

- Harm is larger than benefits – Although they may agree that there are some positive effects of warez on the world, they argue that its benefits cannot offset its harms. For example, copyright holders need to use their market advantage to earn a living. The warez community is competing with the revenues of the original publishers. When the industry becomes less profitable, less software, games, or music are produced. Consequently, the public will suffer.

- Illegality – They claim the morality of copyright infringement is not disputed in the legal community or mainstream society. As long as cracking groups are citizens of a society, it is not for them to violate laws at will. They would further argue that cracking and warez have no relation to civil disobedience, which is often considered legitimate. They typically justify enforcing copyright for the same reasons that laws against burglary are enforced.

- Fallacy of ambiguity – Some people feel that many pro-warez arguments are often just variations of the same "compositional fallacy" theme argumentatively; for example, many warez people in "the scene" see themselves as operating under the "Robin Hood" agenda, where they "take from the rich and give to the poor". However, in reality it is generally irrelevant how "rich or poor" are those whose works are being copied, or what is the economical situation of those who take their works without compensation. Most of the time, almost everything that can be illegally distributed in the scene, will be.

- Morality – There is a wide range of alternative software available for free. Many people find that it is better to use the legal alternatives instead of using illegal copies.

- Professional pride – Taking the work of others without compensation is almost like stealing from yourself.

- Similarity between copyright infringement and digital property theft – Pirating software without permission is similar to copying someone's personal information without permission, such as credit card numbers, personal password or someone's DNA information.

- Logical fallacy of the victimless crime argument – The "I wouldn't have bought it anyway" argument, the truthfulness of the sentence itself presumes a situation where it is taken for granted that the knowledge itself, about the chance of acquiring an illegal copy of the product in question, doesn't in any way change the potential interest of buying it. However, if one already knows beforehand that it is possible to obtain a copy illegally, and decides to do so, there is afterwards no way of really knowing whether or not the person in question would have bought it. This is because the knowledge about the possibility of obtaining an illegal copy for free might turn down the person's interest to buy it, so the potential chance for using warez in the first place might actually effectively sometimes become the reason for not obtaining the legal version.

Legality

Warez is often a form of copyright infringement punishable as either a civil wrong or a crime. The laws and their application to warez activities may vary greatly from country to country. Generally, however, there are four elements of criminal copyright infringement: the existence of a valid copyright, that copyright was infringed, the infringement was willful and the infringement was either for commercial gain or substantial (a level often set by statute).

In most jurisdictions, copyright infringement may be established by reproduction of the copyrighted work. This reproduction can often be shown by the presence of an authorized electronic copy of the work on a server. Most common defenses to copyright infringement, such as the First sale doctrine and Fair use, do not fare well in courts.

The first sale doctrine is a defense to infringement of the distribution right. It permits a lawful purchaser of a copyrighted work to resell or otherwise dispose of it. This, however, is not a defense to the reproduction right.

In addition, fair use is an equitable defense, but its application will vary greatly depending on the facts and circumstances of the case. Most courts apply some form of balancing test examining the scope of infringement, the effect on the copyright owner's rights (eg. his or her ability to sell the work), the amount of the work copied, and the purpose of the infringement. Courts have been somewhat hostile to defendants asserting non-commercial use. In small scale cases, courts are more receptive to arguments regarding the effect on the copyright owner's market.

Important loopholes in the United States were closed with the passage of the No Electronic Theft Act (NET Act). Historically, the criminal copyright law required the infringement be for financial gain. Among other things, the NET Act altered the definition of financial gain to include bartering and trading. In addition, members of warez groups may also prosecuted for their participation in a criminal enterprise.

English law

In English law, any modification of data stored on a computer so that unauthorised access is gained to software packages, games, movies, and music would be a criminal offence under s3 Computer Misuse Act 1990. So, if a read-only music CD is placed in a PC drive and the contents loaded into the computer's memory for playing, any crack that allows the music to be copied and stored on the machine or an MP3 player would commit the offence in theory but, so far, there have been no prosecutions on this set of facts. More generally, ss16 and 20 Copyright, Designs & Patents Act 1988 (as amended by the Copyright, etc. and Trade Marks (Offences and Enforcement) Act 2002) protect copyrighted materials, and people who distribute and download copyrighted recordings without permission are liable to face civil actions for damages and penalties (the largest to date is £6,500). As in the United States, the enforcement agencies are able to identify the IP addresses and the ISPs are obliged to disclose the name and address of the owner of each such internet account.

Criminal offences

For the most part, the criminal law is only used for commercial piracy with one exception, and an offence is committed when, knowing or reasonably suspecting that the files are illegal copies, and without the permission of the copyright owner, a person:

- makes unauthorised copies e.g. burning music files or films on to CD-Rs or DVD-Rs;

- distributes, sells or hires out unauthorised copies of CDs, VCDs and DVDs;

- on a larger scale, distributes unauthorised copies as a commercial enterprise on the internet;

- possesses unauthorised copies with a view to distributing, selling or hiring these to other people;

- while not dealing commercially, distributes unauthorised copies of software packages, books, music, games, and films on such a scale as to have an measurable impact on the copyright owner's business.

The penalties for these "copyright theft" offences depend on the seriousness of the offences:

- before a magistrates' Court, the penalties for distributing pirated files are a maximum fine of £5,000 and/or six months imprisonment;

- in the Crown Court, the penalties for distributing pirated files are an unlimited fine and/or up to 10 years imprisonment.

Also note s24 Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 which creates a range of offences relating to the distribution of any device, product or component which is primarily designed, produced, or adapted for the purpose of enabling or facilitating the circumvention of effective technological measures. When this is for non-commercial purposes, it requires there to be a measurable effect on the rights holder's business.

See also

- Copyright infringement of software

- Crack introduction

- List of warez groups

- The iSO News

- Grey hat - includes details on the anti-piracy.se case, alledgly linking Swedish anti-piracy organisation and Swedish authorities to criminal actions.

Notes

References

- Warez - The Jargon Wiki

- 2600 A Guide to Piracy – An article on the warez scene (ASCII plaintext and image scans from 2600: The Hacker Quarterly)

- "The Shadow Internet" – An article about modern day warez "top sites" at Wired News.

- The Darknet and the Future of Content Distribution

- BSA - Global Piracy Study - 2005 (PDF)

- BSA - Global Piracy Study - 2004 (PDF)

- Ordered Misbehaviour – The Structuring of an Illegal Endeavor by Alf Rehn. A study of the illegal subculture known as the "warez scene". (PDF)

External links

- Warez A very complete archive of warez, and news, historical information also.

- Defacto2 – A very complete archive of scene news, historical information with an extensive nfo, emag and cracktro database.

- Piracy Textfiles – A historical collection of documents released by warez-related individuals.

- How to Become an Elite Warez Trader – A humorous take on the mid-1990s scene.

- www.welcometothescene.com – A monthly internet show based upon the "scene".

- www.welcometoTEHscene.com – A parody of the above.

- Warez Trading and Criminal Copyright Infringement – An article on warez trading and the law, including a recap of US prosecutions under the No Electronic Theft Act.

- A Guide To Internet Piracy Insider report about "the warez scene"

- Piracy and Unconventional Wisdom – Uncommon view of a software developer