Identity document

An identity document (or I.D.) is a piece of documentation designed to prove the identity of the person carrying it. Unlike other forms of documentation, which only have a single purpose such as authorizing bank transfers or proving membership of a library, an identity document simply asserts the bearer's identity. If an identity document is in the form of a small standard-sized card, such as an ISO 7810 card, it is called an identity card.

Identity cards can be controversial, as depending on the way they are used by government. If the circumstances where they must be produced covers everyday life and if enough information about use is stored on databases, this can make government surveillance of citizens much easier.

In some countries, a person's national identification number may be printed on their identity card, either in addition to the document's serial number, or instead of the latter.

Types of identity cards

Modern identity cards bear little resemblance to the original "photograph on piece of cardboard" and are often hi-tech smartcards which can be read by computer.

Where the identity card is issued by a state, it asserts a unique single civil identity for a person, thus defining that person's identity purely in relation to the state. New technologies allow identity cards to contain biometric information, such as photographs, face, hand or iris measurements, or fingerprints.

Other information typically present on the cards — or on the supporting database — includes full name, parents' names, address, profession, nationality in multinational states, and blood type.

Legal impact

Laws usually limit who is authorized to require an identification (for example limiting it to police, immigration officers etc), though practice usually broadens the range to many public and private entities: for example, a shopkeeper or cashier may request an ID document to be shown by a client paying with a credit card or cheque. Similarly, in circumstances where law enforcement can legally ask for identification, not being able to show an ID document, though legal, may result in being taken to a police station for further identification, depending on the jurisdiction.

In many cases, other forms of documentation such as a driver's license, passport, or Medicare card serve a similar function, identifying the bearer in a variety of contexts. However, possession of these documents is typically optional from a legal point of view.

Not carrying a required identity card can be beneficial for people who wish to avoid detection. It may also help in some illegal dealings; for instance, in certain countries, the procedures for deporting illegal immigrants whose age, identity or nationality cannot be formally established are more complex than those for whom they can be readily asserted, giving the illegal immigrant more time to prepare his or her defense.

Arguments for and against identity cards

Arguments about identity cards is largely limited to Anglo-Saxonic common-law countries. In most countries where an ID system is present, it is seen as a commonplace item that nobody argues about.

In the United Kingdom and the United States especially, state-issued compulsory identity cards are a source of great controversy. Some people regard them as a gross infringement of privacy and civil liberties, whilst others regard them as uncontroversial.

Usually, mainstream criticism is actually directed towards possibilities of extensive abuse of identity documents; central databases with storage of sensitive data are especially feared. While such systems have been proposed in some countries, in most countries with identification documents they have not been implemented.

Arguments in favour

Supporters of identity cards argue that:

- identity cards would be a useful administrative tool that will increase government efficiency and cut down on crime;

- opposition to identity cards would be caused by the necessity of having "something to hide"; opponents counter that also law-abiding citizens can want information to remain confidential for various reasons (as a person trying to make their whereabouts unknown to a stalker);

- if a state doesn't issue identity cards, private companies will require equivalent documents, such as a driver license, which are not properly suited for identity purposes;

- crimes such as identity theft would be drastically reduced, and are indeed unknown in countries where identity cards are required to open a bank account.

- law enforcers can discover people who suffer from dissociative identity disorder (e.g. Billy Milligan) when they found patients claim their names which is not consistent with the name on their identity cards.

Arguments against

Economic and social liberals have a generally negative attitude towards identity cards on the principle that if society already works adequately without them, they should not be imposed by government, on the principle that "the government that governs best, governs least". Some opponents have pointed out that extensive lobbying for identity cards has been undertaken, in countries without compulsory identity cards, by IT companies who will be likely to reap rich rewards in the event of an identity card scheme being implemented.

Very often, opposition to identity cards is born out of the suspicion that they will be used to track anyone's movements and private life, possibly endangering one's privacy; for instance, a person will probably not want others to know he or she is attending meetings with Alcoholics Anonymous. In countries currently using identity cards, there is no mechanism for this. However the proposed British ID card (see next section) will involve a series of linked databases, to be managed by the private sector. Managing disparate linked systems with a range of institutions and any number of personnel having access to them is a potential security disaster in the making.[1]

Opponents have also argued that some nations require the card to be carried at all times. This is not necessarily impractical, as an ID is no more cumbersome than a credit card. However, opponents point out that a requirement to carry an identity card at all times can lead to arbitrary requests from card controllers (such as the police). This can lead to functionality creep whereby carrying a card becomes de facto if not de jure compulsory, as with the Social Security number, which is now widely used as ID. That is, everyone carries their card around anyway even though there is no law. It would be inconvenient, for example, to go home and get the card if stopped by police.

Some opponents make comparisons with totalitarian governments, which issued identity cards to their populations, and used them oppressively.

- They point out that the issuing of unique biometric identities was taken to its logical conclusion within living memory by the Nazis (see Godwin's Law), when they tattooed unique concentration-camp detainees numbers on the arms of people taken to be processed by the Final Solution.

- More recently, the apartheid-era government of South Africa used pass books as internal passports to oppress that country's black population.

Identity cards worldwide

Countries with compulsory identity cards

According to Privacy International, as of 1996, around 100 countries had compulsory identity cards. They also stated that "virtually no common law country has a card".

The term "compulsory" may have different meanings and implications in different countries. The compulsory character may apply only after a certain age. Often, a ticket can be given for being found without one's identification document, or in some cases a person may even be detained until the identity is ascertained. In practice, random controls are rare, except in police states.

- Argentina: Documento Nacional de Identidad. Issued at birth. Updated at 8 and 16 years old. Small booklet, dark green cardboard cover. The first page states the name, date and place of birth, along with a picture and right thumb print. It's a hand written form, and the newer models have an adhesive laminate for the first page. Next pages issue address changes, wish to donate organs, military service, and vote log. Half of the pages have the DNI (a unique number), perforated through the first half of the book. Prior to DNI was the Libreta Civica ("Civic booklet"), for women, and the Libreta de Enrolamiento ("Enrollment Booklet"), for men. A few years ago there was a big scandal with the electronic DNIs that were going to be manufactured by Siemens, and it was decided that no private corporation could control the issuing of national identity. The federal police also have an identity that is valid sometimes instead of the DNI, which many people prefer to carry because after the loss of DNI there is a long process (caused only by bureaucratic reasons) in which the person is limited in some situations which require the DNI. Random controls cannot be made without a judge's order, except in situations such as military border checkpoints.

- Belgium: See State Registry (in Dutch, French and German) The card is first issued at age 12, compulsory by 15.

- Brazil: Cédula de identidade. Compulsory to be issued and carried since the age of 18. It's usually issued by each state's Public Safety Secretary, or sometimes by the Armed Forces. There is a national standard, but each state can include minor differences. The front has a picture, right thumb print and signature. The verse has the unique number (RG, registro geral), expedition date, name of the person, name of the parents, place and date of birth, and other info. It is green and plastified, officially 102 × 68 mm[2], but the lamination tends to make it slightly larger than the ISO 7810 ID-2 standard of 105 × 74 mm, resulting in a tight fit in most wallets. Only recently the driver's licence received the same legal status of an identity card in Brazil. There are also a few other documents, such as cards issued by the national councils of some professions, which are considered equivalent to the national identity card for most purposes.

- Bulgaria: лична карта in Cyrillic alphabet (or "lična karta" in Latin transliteration) is first issued and is compulsory after turning the age of 14. The new Bulgarian ID cards were introduced in 2000. They follow the general pattern in the EU and replaced the old, Soviet-style "internal passports", also known as "green passports". It is worth mentioning that during communism (1945-1989), to receive an "international passport", especially one allowing to travel to a Western country, was considered an achievement. Not all Bulgarian citizens had the right to travel abroad, and those who travelled outside the Soviet bloc underwent strict investigation for possible links with political enemies of the regime.

- Chile: Carnet de identidad. First issued at age 2 or 3, it is compulsory at 18.

- People's Republic of China: First issued at school age, the Jumin Shengfenzheng becomes compulsory at 16.

- Croatia: The Osobna iskaznica is compulsory at 16.

- Cuba: Carné de identidad

- Czech Republic: Občanský průkaz, compulsory at 15.

- Egypt

- Estonia: See id.ee (in Estonian), [3] (in English)

- Germany: Personalausweis (German Wikipedia): It is compulsory at age 16 to possess either a "Personalausweis" or a passport, but not to carry it. While police officers and some other officials have a right to demand to see one of those documents, the law does not state that one is obliged to submit the document at that very moment, but only that one must be able to submit it in the future (that is, bring it to the police station/municipal office the next day, or know where it is and show it to the police at your home, and so on.) Fines may only be applied if an identity card or passport is not possessed at all, if the document is expired or if one explicity refuses to show ID to the police.

- Greece

- Hong Kong: See main article Hong Kong Identity Card. Identity cards have been used since 1949, and been compulsory since 1980. Children are required to obtain their first identity card at age 11, and must change to an adult identity card at age 18.

- Indonesia: Kartu Tanda Penduduk (KTP; link goes to Indonesian Wikipedia)

- Israel: The Teudat Zehut is first issued at age 16 and is compulsory by 18.

- Italy: Carta d'Identità (Italian Wikipedia)

- Hungary: See [4] (in Hungarian) It is compulsory to possess and carry either an ID card or a passport from the age of 14. A driving license can be also used for identification from the age of 17.

- Luxembourg

- Latvia: See [5] (In English) An identity card or passport is the mandatory personal identification document for a citizen of Latvia or a non-citizen who lives in Latvia and has reached 15 years of age.

- Madagascar: Kara-panondrom-pirenen'ny teratany malagasy (Carte nationale d'identité de citoyen malagasy). Possession is compulsory for Malagasy citizens from age 18 (by decree 78-277, 1978-10-03).

- Malaysia: MyKad. Issued at age 12, it is updated at 18.

- Netherlands: Since 2005, every person over 14 years of age must always carry a passport, driving licence, Dutch/European identity card or (for foreigners) an identification document.[6]

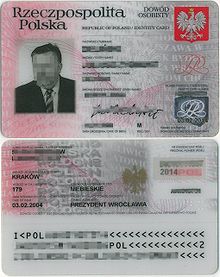

- Poland: Dowód osobisty (Polish Wikipedia): The card is compulsory at 18. The relative law is roughly similar to the German one.

- Portugal: Bilhete de identidade (Portuguese Wikipedia): The card is compulsory at 10, but can be issued before if needed.

- Romania: The Carte de identitate is compulsory at 14.

- Russia: Internal passport

- Serbia: The Lična Karta (Лична Карта) is compulsory at 18.

- Singapore: It is compulsory for all citizens and permanent residents to apply for the National Registration Identity Card from age 15 onwards, and to re-register their cards for a replacement at age 30. It is not compulsory for bearers to hold the card at all times, nor are they compelled by law to show their cards to police officers conducting regular screening while on patrol, for instance. Failure to show any form of identification, however, may allow the police to detain suspicious individuals until relevant identification may be produced subsequently either in person or by proxy. The NRIC is also a required document for some government procedures, commercial transactions such as the opening of a bank account, or to gain entry to premises by surrendering or exchanging for an entry pass. Failure to produce the card may result in denied access to these premises or attainment of goods and services. Immigration & Checkpoints Authority

- Slovakia: Občiansky preukaz (Citzens card) is compulsory at the age of 15. It serves the purpose of general identification towards the authorities. It features a photograph, date of birth and the address. Every card has a unique number.

- Slovenia: The Osebna izkaznica is compulsory at 18, but can be issued to citizens under 18 on request by their parent or legal guardian.

- Spain: The Documento Nacional de Identidad (DNI) (Spanish Wikipedia) is compulsory at 14, can be issued before if necessary (to travel to other European countries, for example). It is to be replaced by Electronic DNI.

- Thailand

- Turkey

Countries with non-compulsory identity cards

- Australia: In 1985, there was a failed proposal to create an Australia Card. In 2006 the Australian Government reproposed the concept of a compulsory National Identity Card, which is still under investigation, and has subsequently announced the introduction a non-compulsory National Services Card that will act as a gateway to services administered by | The Department of Human Services.

- Austria

- Canada

- Finland

- France (see extended discussion below)

- Sweden has recently started issuing national identity cards, but they are by no means compulsory. Most Swedes have not even seen one. Commonly people use their driving licences as ID, or an ID issued by banks or the post. Some big companies and authorities also issue ID cards to their employees which are usually accepted in Sweden as identification.

- Switzerland

France

In France, it is forbidden to walk around without one's ID and at least 15 euros, a remnant of the anti-vagabond laws which were voted during the 19th century to fix in some location workers).

The country has had a national ID card since 1940, when it helped the Vichy authorities identify 76,000 for deportation as part of the Holocaust. Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben often underlines this, showing how anthropometry may be used by the state.

In the past, identity cards were compulsory, had to be updated each year in case of change of residence and were valid for 10 years, and their renewal required paying a fee. In addition to the face protograph, the card included the family name, first names, date and place of birth, and the national identity number managed by the national INSEE registry, and which is also used as the national service registration number, as the Social Security account number for health and retirement benefits, for access to court files and for tax purposes.

Later, the laws were changed so that any official and certified document (even if expired and possibly unusable abroad) with a photograph and a name on it, issued by a public administration or enterprise (such as a railroad transportation card, a student card, a driving licence or a passport) can be used to prove one's identity. Also, law enforcement (police, gendarmerie) can now accept photocopies of these documents when performing identity checks, provided that the original document is presented within two weeks. For finacial transactions, any of these documents must be equally accepted as proof of identity.

The current identity cards are now issued free of charge, and non-compulsory. Legislation has been published for a proposed compulsory biometric card system, which has been widely criticised, among others by the "National commission for computing and liberties" (Commission nationale de l’informatique et des libertés, CNIL), the national authority and regulator on computing systems and databases. Identity cards issued since 2004 include basic biometric information (a digitized fingerprint record, a printed digital photograph and a scanned signature) and various anti-fraud systems embedded within the plastic-covered card.

The next generation of the French green card, named "Carte Vitale", for the Social Security benefit (which already includes a chip and a magnetic stripe currently containing very little information) will include a digital photograph and other personal medical information in addition to identity elements. It may then become a substitute for the National Identity Card.

Countries with no identity cards

- Australia: In 1985, there was a failed proposal to create an Australia Card. In 2006 the Australian Government reproposed the concept of a compulsory National Identity Card, which is still under investigation, and has subsequently announced the introduction a non-compulsory National Services Card that will act as a gateway to services administered by Centrelink, the national welfare agency, and Medicare Australia, the national health insurance service.

- Denmark

- Iceland

- India

- Ireland

- Japan

- New Zealand

- Norway

- South Korea

- United Kingdom: There is no national identity card as of 2006, but there have been highly controversial plans to introduce them. See main article British national identity card.

- United States

United States

There is no true national identity card in the United States of America, in the sense that there is no federal agency with nationwide jurisdiction that directly issues such cards to all American citizens. All legislative attempts to create one have failed due to tenacious opposition from libertarian and conservative politicians, who regard the national identity card as the mark of a totalitarian society. Driver's licenses issued by the various states (along with special cards issued to non-drivers) are often used in lieu of a national identification card and are often required for boarding airline flights or entering office buildings. Recent (2005) federal legislation that tightened requirements for issuance of driver's licenses has been seen by both supporters and critics as bringing the United States much closer to a de facto national identity card system.

Note: As noted above, certain countries do not have national ID cards, but have other official documents that play the same role in practice (e.g. driver's license for the United States). While a country may not make it de jure compulsory to own or carry an identity document, it may be de facto strongly recommended to do so in order to facilitate certain procedures.

Other non-sovereign state ID cards

Some Basque nationalist organizations are issuing para-official identity cards (Euskal Nortasun Agiria) as a means to reject the nationality notions implied by Spanish and French compulsory documents. Then, they try to use the ENA instead of the official document.

For the people of Western Sahara, pre-1975 Spanish cards are the main proof that they were Saharaui citizens as opposed to recent Moroccan colonists. They would be thus allowed to vote in an eventual self-determination referendum.

Non-national identity cards

Some companies and government departments issue ID cards for security purposes; they may also be proof of a qualification. For example, all taxi drivers in the UK and Hong Kong carry ID cards. In Queensland, anyone working with children has to take a background check and get issued a Blue Card.

See also

- Anthropometry

- Biometrics

- Home Return Permit, a special kind a national ID card issued for PRC citizens living in Hong Kong and Macao.

- Identity document forgery

- Pass Law, which mandated people carry a pass book in apartheid South Africa

- Passport

- Visa (document)