Upper respiratory tract

| Upper respiratory tract | |

|---|---|

Conducting passages. | |

| Identifiers | |

| FMA | 45661 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

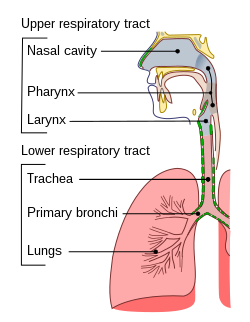

The upper respiratory tract or upper airway primarily refers to the parts of the respiratory system lying outside of the thorax[1] or above the sternal angle. Another definition commomly used in medicine is the airway above the glottis or vocal cords. Some specify that the glottis (vocal cords) is the defining line between the upper and lower respiratory tracts;[2] yet even others make the line at the cricoid cartilage.[3]

Upper respiratory tract infections are among the most common infections in the world.

Components

- Nose, nasal cavity, and paranasal sinuses

- Pharynx

- Larynx (The larynx can be considered part of the upper respiratory tract,[4] the lower respiratory tract, or both, depending on the source.). The pharynx is also called the voice box and has the associated cartilage that produce sound.

Role in respiration

Unlike the trachea and bronchi, the upper airway is a collapsible, compliant tube. As such, it has to be able to withstand suction pressures generated by the rhythmic contraction of the diaphragm that sucks air into the lungs. This is accomplished by the rhythmic contraction of upper airway muscles, such as the genioglossus (tongue) and the hyoid muscles. In addition to rhythmic innervation from the respiratory center in the medulla oblongata, the motoneurons controlling the muscles also receive tonic innervation that sets a baseline level of stiffness and size.

Upper airway during sleep

During non-REM sleep, the tonic drive to most respiratory muscles of the upper airway is inhibited. This has two consequences:

- The upper airway becomes more floppy.

- The rhythmic innervation results in weaker muscle contractions because the intracellular calcium levels are lowered, as the removal of tonic innervation hyperpolarizes motoneurons, and consequently, muscle cells.

However, because the diaphragm is largely driven by the autonomous system, it is relatively spared of non-REM inhibition. As such, the suction pressures it generates stay the same. This narrows the upper airway during sleep, increasing resistance and making airflow through the upper airway turbulent and noisy. For example, one way to determine whether a person is sleeping it to listen to their breathing - once the person falls asleep, their breathing becomes noticeably louder. Not surprisingly, the increased tendency of the upper airway to collapse during breathing in sleep can lead to snoring, a vibration of the tissues in the upper airway. This problem is exacerbated in overweight people when sleeping on the back, as extra fat tissue may weigh down on the airway, closing it. This can lead to sleep apnea.

See also

References

- ^ I. Edward Alcamo; John Bergdahl (29 July 2003). Anatomy Coloring Workbook. The Princeton Review. pp. 238–. ISBN 978-0-375-76342-7. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ Ronald M. Perkin; James D Swift; Dale A Newton (1 September 2007). Pediatric hospital medicine: textbook of inpatient management. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 473–. ISBN 978-0-7817-7032-3. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ Jeremy P. T. Ward; Jane Ward; Charles M. Wiener (2006). The respiratory system at a glance. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 11–. ISBN 978-1-4051-3448-4. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ Sabyasachi Sircar (2008). Principles of medical physiology. Thieme. pp. 309–. ISBN 978-3-13-144061-7. Retrieved 26 April 2010.