Arch

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (December 2009) |

1. Keystone 2. Voussoir 3. Extrados 4. Impost 5. Intrados 6. Rise 7. Clear span 8. Abutment

An arch is a structure that spans a space and supports structure and weight above it. Arches appeared as early as the 2nd millennium BC in Mesopotamian brick architecture [1] and their systematic use started with the Ancient Romans who were the first to apply the technique to a wide range of structures.

Basic concepts

An arch is a pure compression form.[2] It can span a large area by resolving forces into compressive stresses and, in turn eliminating tensile stresses. This is sometimes referred to as arch action.[3] As the forces in the arch are carried to the ground, the arch will push outward at the base, called thrust. As the rise, or height of the arch decreases, the outward thrust increases.[4] In order to maintain arch action and prevent the arch from collapsing, the thrust needs to be restrained, either with internal ties, or external bracing, such as abutments.[5]

Fixed arch vs hinged arch

The most common true arch configurations are the fixed arch, the two-hinged arch, and the three-hinged arch.

- The fixed arch is most often used in reinforced concrete bridge and tunnel construction, where the spans are short. This type of arch is considered to be statically indeterminate and is subject to additional internal stress caused by thermal expansion and contraction.[6]

- The two-hinged arch is most often used to bridge long spans.[5] This type of arch has pinned connections at the base. Unlike the fixed arch, the pinned base is allowed to rotate[7] and is thus not affected by thermal change. The two-hinged arch is also statically indeterminate, although not to the degree of the fixed arch.[5]

- The three-hinged arch is hinged at the mid-span, and at the two bases of the arch. This type of arch is statically determinate. It is most often used for medium-span structures, such as large building roofs. The advantage of the three-hinged arch is that the pinned bases are more easily developed than fixed ones, allowing for shallow, bearing-type foundations in medium-span structures. In the three-hinged arch, "thermal expansion and contraction of the arch will cause vertical movements at the peak pin joint but will have no appreciable effect on the bases," further simplifying the foundation design.[5]

Arch forms

Arches have many forms, but all fall into three basic categories: Circular, pointed, and parabolic. Arches can also be reconfigured to produce vaults and arcades.

- Arches with a circular form were commonly employed by the builders of ancient, heavy masonry arches.[8] Ancient Roman builders relied heavily on the circular arch to span large, open areas. Several circular arches placed in-line, end-to-end, form an arcade, such as the Roman aqueduct.[9]

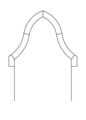

- Pointed arches were most often used by builders of Gothic-style architecture.[10] The advantage to using a pointed arch, rather than a circular arch, is that the arch action in a pointed arch produces less thrust at the base. This innovation allowed for taller and more closely-spaced openings, typical of Gothic architecture.[11] [12]

- Vaults are essentially “adjacent arches are assembled side by side.” If vaults intersect, complex forms are produced with the intersections. The forms, along with the “strongly expressed ribs at the vault intersections, were dominant architectural features of Gothic cathedrals.”[13]

- The parabolic arch employs the principle that when weight is uniformly applied to an arch, the internal compression resulting from that weight will follow a parabolic profile. Of any arch type, the parabolic arch produces the most thrust at the base, but can span large areas. It is commonly used in bridge design, where long spans are needed.[14]

History

True arches, as opposed to corbel arches, were known by a number of civilizations in the Ancient Near East, the Levant, and Mexico, but their use was infrequent and mostly confined to underground structures such as drains where the problem of lateral thrust is greatly diminished.[15] A rare exception is the bronze age arched city gate of Ashkelon (modern day Israel), dating to ca. 1850 B.C.[16] An early example of a voussoir arch appears in the Greek Rhodes Footbridge.[17] In 2010, a robot discovered a long arch-roofed passageway underneath the Pyramid of Quetzalcoatl which stands in the ancient city of Teotihuacan north of Mexico City, dated to around 200 AD.[18]

The ancient Romans learned the arch from the Etruscans, refined it and were the first builders to tap its full potential for above ground buildings:

The Romans were the first builders in Europe, perhaps the first in the world, fully to appreciate the advantages of the arch, the vault and the dome.[19]

Throughout the Roman empire, their engineers erected arch structures such as bridges, aqueducts, and gates. They also introduced the triumphal arch as a military monument. Vaults began to be used for roofing large interior spaces such as halls and temples, a function which was also assumed by domed structures from the 1st century BC onwards.

The segmental arch was first built by the Romans who realized that an arch in a bridge did not have to be a semicircle,[20][21] such as in Alconétar Bridge or Ponte San Lorenzo. They were also routinely used in house construction as in Ostia Antica (see picture).

The semicircular arch was followed in Europe by the pointed Gothic arch or ogive whose centreline more closely followed the forces of compression and which was therefore stronger. The semicircular arch can be flattened to make an elliptical arch as in the Ponte Santa Trinita. Both the parabolic and the catenary arches are now known to be the theoretically strongest forms. Parabolic arches were introduced in construction by the Spanish architect Antoni Gaudí, who admired the structural system of Gothic style, but for the buttresses, which he termed “architectural crutches”. The catenary and parabolic arches carry all horizontal thrust to the foundation and so do not need additional elements.

The horseshoe arch is based on the semicircular arch, but its lower ends are extended further round the circle until they start to converge. The first known built horseshoe arches are known from Aksum (modern day Ethiopia and Eritrea) from around the 3rd–4th century, around the same time as the earliest contemporary examples in Roman Syria, suggesting either an Aksumite or Syrian origin for the type of arch.[22][page needed]

Construction

Since it is a pure compression form, the arch is useful because many building materials, including stone and unreinforced concrete can resist compression but are weak when tensile stress is applied to them.[23]

An arch is held in place by the weight of all of its members, making construction problematic. One answer is to build a frame (historically, of wood) which exactly follows the form of the underside of the arch. This is known as a centre or centring. The voussoirs are laid on it until the arch is complete and self-supporting. For an arch higher than head height, scaffolding would in any case be required by the builders, so the scaffolding can be combined with the arch support. Occasionally arches would fall down when the frame was removed if construction or planning had been incorrect. (The A85 bridge at Dalmally, Scotland suffered this fate on its first attempt, in the 1940s[citation needed]). The interior and lower line or curve of an arch is known as the intrados.

Old arches sometimes need reinforcement due to decay of the keystones, forming what is known as bald arch.

The gallery shows arch forms displayed in roughly the order in which they were developed.

-

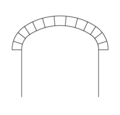

Round arch or Semi-circular arch

-

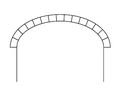

Segmental arch or arch that is less than a semicircle

-

Unequal round arch or Rampant round arch

-

Shouldered flat arch -see also jack arch

-

Trefoil arch, or Three-foiled cusped arch

-

Parabolic arch

In reinforced concrete construction, the principle of the arch is used so as to benefit from the concrete's strength in resisting compressive stress. Where any other form of stress is raised, such as tensile or torsional stress, it has to be resisted by carefully placed reinforcement rods or fibres.[24]

Construction of adobe arches

Gallery showing various stages of construction of arches made of adobe- mud- bricks using local materials:

-

Adobe arches in Merzouga, Morocco. These arches rest upon concrete pillars and have a concrete bar across them for strength.

-

Ready for final touches (Merzouga, Morocco)

-

Notice the adobe bricks. (Merzouga, Morocco)

-

Bricks made from local mud. (Merzouga, Morocco)

-

Arches supported by concrete pillars. (Merzouga, Morocco)

-

Similar to arches in the mosque in Cordoba, Spain.

-

Completed arch in Merzoura, Morocco.

-

Arches are made of adobe and have to be protected from the rain. Roof is being constructed and is partially finished.

Other types

A blind arch is an arch infilled with solid construction so it cannot function as a window, door, or passageway.

Natural rock formations may also be referred to as arches. These natural arches are formed by erosion rather than being carved or constructed by man. See Arches National Park for examples.

A special form of the arch is the triumphal arch, usually built to celebrate a victory in war. A famous example is the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, France.

Gallery

-

Doubled round archivolts – Igreja de Nossa Senhora da Assunção, Linhares da Beira, Portugal.

-

Stonework arches seen in a ruined stonework building – Burg Lippspringe, Germany

-

Several arches at the Casa Simón Bolívar in Havana, Cuba

-

Arches in the nave of the church in monastery of Alcobaça, Portugal

-

The Arc de Triomphe, Paris; a 19th-century triumphal arch modeled on the classical Roman design

-

The Second Wembley Stadium, in London, built in 2007

-

Arches in one of the porticos of Mosque of Uqba also known as the Great Mosque of Kairouan, city of Kairouan, Tunisia

-

Lucerne railway station, Switzerland

-

Lancet arches in Salisbury Cathedral

See also

- Arcade (architecture)

- Arch bridge

- Corbelled arch

- Blind arch

- Natural arch

- Order moulding

- Skew arch

- Suspension bridge

- Triumphal arch

- Golden Arches

References

- ^ "Ancient Mesopotamia:Architecture". The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- ^ Dym, Clive L. (2011). "Stress and Displacement Estimates for Arches" (PDF). JOURNAL OF STRUCTURAL ENGINEERING. 49. doi:10.1061. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Check|doi=value (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Vaidyanathan, R (2004). Structural Analysis, Volume 2. USA: Laxmi Publications. p. 127. ISBN 8170085845.

- ^ Ambrose, James (2012). Building Structures. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 30.

- ^ a b c d Ambrose, James (2012). Building Structures. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-470-54260-6.

- ^ Ambrose, James (2012). Building Structures. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-470-54260-6.

- ^ Luebkeman, Chris H. "Support and Connection Types". MIT.edu Architectonics: The Science of Architecture. MIT.edu. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ Ambrose, James (2012). Building Structures. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-470-54260-6.

- ^ Oleson, John (2008). The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World. USA: Oxford University Press. p. 299. ISBN 0195187318.

- ^ Crossley, Paul (2000). Gothic Architecture. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. p. 58. ISBN 0300087993.

- ^ Hadrovic, Ahmet (2009). STRUCTURAL SYSTEMS IN ARCHITECTURE. On Demand Publishing. p. 289. ISBN 1439259445.

- ^ MHHE. "STRUCTURAL SYSTEMS IN ARCHITECTURE". MHHE.com. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ Ambrose, James (2012). Building Structures. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-470-54260-6.

- ^ Ambrose, James (2012). Building Structures. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-470-54260-6.

- ^ Rasch 1985, p. 117

- ^ Oldest arched gate in the world restored

- ^ Galliazzo 1995, p. 36; Boyd 1978, p. 91

- ^ Teotihuacan ruins explored by a robot, AP report in the Christian Science Monitor, November 12, 2010

- ^ Robertson, D.S.: Greek and Roman Architecture, 2nd edn., Cambridge 1943, p.231

- ^ Galliazzo 1995, pp. 429–437

- ^ O’Connor 1993, p. 171

- ^ Stuart Munro-Hay, Aksum: A Civilization of Late Antiquity. Edinburgh: University Press. 199

- ^ Reid, Esmond (1984). Understanding Buildings: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. p. 12. ISBN 0-262-68054-8.

- ^ Allen, Edward (2009). Fundamentals of Building Construction. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. p. 529. ISBN 978-0-470-07468-8.

- Notes

- Boyd, Thomas D. (1978), "The Arch and the Vault in Greek Architecture", American Journal of Archaeology, 82 (1): 83–100 (91), doi:10.2307/503797

- Galliazzo, Vittorio (1995), I ponti romani, vol. Vol. 1, Treviso: Edizioni Canova, ISBN 88-85066-66-6

{{citation}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - O’Connor, Colin (1993), Roman Bridges, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-39326-4

- Rasch, Jürgen (1985), "Die Kuppel in der römischen Architektur. Entwicklung, Formgebung, Konstruktion", Architectura, vol. 15, pp. 117–139

- Roth, Leland M (1993). Understanding Architecture: Its Elements History and Meaning. Oxford, UK: Westview Press. ISBN 0-06-430158-3. pp. 27–8

External links

DIYinfo.org's Constructing Brick Arches Wiki - A wiki on how to construct brick arches around the house DIYinfo.org's Constructing Timber Framed Arches Wiki - Similar to the brick arches but extra information for timber arches