Catholic Church and health care

The Roman Catholic Church is the largest non-government provider of health care services in the world.[1] Its involvement in the field is born of Catholic social teaching.

From ancient times, Christian emphasis on practical charity gave rise to the development of systematic nursing and hospitals and the Church remains heavily engaged in the field. In 2010, the Catholic Church's Pontifical Council for Pastoral Assistance to Health Care Workers said that the Church manages 26% of health care facilities in the world, including hospitals, clinics, orphanages, pharmacies and centres for those with leprosy.[2]

Theological basis: euntes docete et curate infirmos

Catholic social teaching urges concern for the sick. Jesus Christ, whom the church holds as its founder, placed a particular emphasis on care for the sick and outcast, such as lepers. According to the New Testament, he and his Apostles went about curing the sick and annointing of the sick.[3] According to the Gospel of Matthew 25:35-46, Jesus identified so strongly with the sick and afflicted that he equated serving them with serving him:

For I was hungry and you fed me, thirsty and you gave me drink. I was a stranger and you received me in your homes. Naked and you clothed me. I was sick and you took care of me, in prison and you visited me... [W]hatever you did for one of these least brothers of mine, you did for me.

— Passage from the Gospel of Matthew

In a 2013 presentation to its twenty-seventh international conference in 2013, the President of the Pontifical Council for Health Care Workers, Zygmunt Zimowski, said that "The Church, adhering to the mandate of Jesus, ‘Euntes docete et curate infirmos’ (Mt 10:6-8, Go, preach and heal the sick), during the course of her history, which by now has lasted two millennia, has always attended to the sick and the suffering."

In orations such as his Sermon on the Mount and stories such as The Good Samaritan, Jesus called on followers to worship God, act without violence or prejudice and care for the sick, hungry and poor. Such teachings formed the foundation of Catholic Church involvement in hospitals and health care.[3]

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia:[4]

Christ Himself gave His followers the example of caring for the sick by the numerous miracles He wrought to heal various forms of disease including the most loathsome, leprosy. He also charged His Apostles in explicit terms to heal the sick (Luke 10:9) and promised to those who should believe in Him that they would have power over disease (Mark 16:18) [...] Like the other works of Christian charity, the care of the sick was from the beginning a sacred duty for each of the faithful, but it devolved in a special way upon the bishops, presbyters, and deacons. The same ministrations that brought relief to the poor naturally included provision for the sick who were visited in their homes.

Philosophy of Catholic health care

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2013) |

Pope Benedict XVI discussed the philosophy of Catholic health and social services in the following terms:[5]

There will always be suffering which cries out for consolation and help. There will always be loneliness. There will always be situations of material need where help in the form of

concrete love of neighbour is indispensable... [A Love-Caritas, that] does not simply offer people material

help, but refreshment and care for their souls, something which often is even more necessary than material support.

History

Antiquity

The Church has, since ancient times, been heavily involved in health care. Early Christians were noted for tending the sick and infirm, and priests were often also physicians. According to the historian Geoffrey Blainey, while pagan religions seldom offered help to the sick, the early Christians were willing to nurse the sick and take food to them - notably during the small pox epidemic of AD 165-180 and the measles outbreak of around AD 250 and that "In nursing the sick and dying, regardless of religion, the Christians won friends and sympathisers".[3] Among the early saints remembered for this role are the twins Cosmas and Damian.[4] Physicians who trained in Syria, Cosmas and Damien reputedly won many converts by charitably working for no fee.[6]

Christian emphasis on practical charity gave rise to the development of systematic nursing and hospitals after the end of the persecution of the early church. Hospitality was considered an obligation of Christian charity and bishops houses and the valetudinaria of wealthier Christians were used to tend the sick.[4] It is believed that the first church hospitals were constructed in the East. An early hospital may have been built at Constaninople during the age of Constantine by St. Zoticus. St. Basil built a famous hospital at Cæsarea in Cappadocia which "had the dimensions of a city". In the West, Saint Fabiola founded a hospital at Rome around 400.[4]

St Luke the Evangelist, one of the earliest and certainly most influential Christian converts of all time, was a Greek Physician who probably travelled as a ship's doctor.[7]Notable contributors to the medical sciences of those early centuries include Tertullian (born A.D. 160), Clement of Alexandria, Lactantius and the learned St. Isidore of Seville (d. 636). St. Benedict of Nursia (480) emphasised medicine as an aid to the provision of hospitality.[8] The martyr Saint Pantaleon was said to be physician to the Emperor Maximinianus, who sentenced him to death for his Christianity. Since the Middle Ages, Pantaleon has been considered a patron saint of physicians and midwives.[9]

Middle Ages

Geoffrey Blainey likened the Catholic Church in its activities during the Middle Ages to an early version of a welfare state: "It conducted hospitals for the old and orphanages for the young; hospices for the sick of all ages; places for the lepers; and hostels or inns where pilgrims could buy a cheap bed and meal". It supplied food to the population during famine and distributed food to the poor. This welfare system the church funded through collecting taxes on a large scale and possessing large farmlands and estates.[10]

After a period of decline, the Holy Roman Emperor Charlamagne had decreed that a hospital should be attached to each cathedral and monastery. Following his death, the hospitals again declined, but by the tenth century, monasteries were the leading providers of hospital work - among them the Benedictine Abbey of Cluny.[4]

The famous Knights Hospitaller arose as a group of individuals associated with an Amalfitan hospital in Jerusalem, which was built to provide care for poor, sick or injured pilgrims to the Holy Land. Following the capture of the city by Crusaders, the order became a military as well as infirmarian order.[11]

During the Middle Ages, famous physicians and medical researchers included the Abbot of Monte Cassino Bertharius, the Abbot of Reichenau Walafrid Strabo, the Abbess st Hildegarde of Bingen and the Bishop of Rennes Marbodus of Angers.[3] Monasteries of this era were diligent in the study of medicine, and often too were convents. Hildergard of Bingen, a doctor of the church, is among the most distinguished of Medieval Catholic women scientists. Other than theological works, Hildegard also wrote Physica, a text on the natural sciences, as well as Causae et Curae. Hildegard was well known for her healing powers involving practical application of tinctures, herbs, and precious stones.[12]

Charlemagne decreed that each monastery and Cathedral chapter establish a school and in these schools, medicine was commonly taught. At one such school Pope Sylvester II taught medicine.[8] The Benedictine order was noted for setting up hospitals and infirmaries in their monasteries, growing medical herbs and becoming the chief medical care givers of their districts. The Capuchin monks sought a revival of the ideals of Francis of Assisi, offering care after plague struck at Camerino in 1523.[3]

Clergy were active at the School of Salerno, the oldest medical school in Western Europe - among the important churchmen to teach there were Alpuhans, later (1058–85) Archbishop of Salerno and the influential Constantine of Carthage, a monk who produced superior translations of Hippocrates and investigated Arab literature.[8]

In Catholic Spain amidst the early Reconquista, Archbishop Raimund founded an institution for translations, which employed a number of Jewish translators to communicate the works of Arabian medicine. Influenced by the rediscovery of Aristotelean thought, churchmen like the Dominican Albert Magnus and the Franciscan Roger Bacon made significant advances in the observation of nature.

Through the devastating Bubonic Plague, the Franciscans were notable for tending the sick. The apparent impotence of medical knowledge against the disease prompted critical examination. Medical scientists came to divide among anti-Galenists, anti-Arabists and positive Hippocratics.[8] St. Roch is venerated as a care-giver to the victims of plague.[13]

In Renaissance Italy, the Popes were often patrons of the study of anatomy and Catholic artists such as Michelangelo advanced knowledge of the field through such studies as sketching cadavers to improve his portraits of the crucifixion.[8]

Development of modern medicine

In modern times, the Catholic Church is the largest non-government provider of health care in the world. Catholic religious have been responsible for founding and running networks of hospitals across the world where medical research continues to be advanced.[14]

Europe

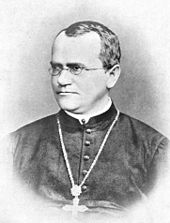

Catholic scientists in Europe (many of them clergymen) made a number of important discoveries which aided the development of modern science and medicine. Catholic women were also among the first female professors of medicine, as with Trotula of Salerno the 11th century pysician and Dorotea Bucca who held a chair of medicine and philosophy at the University of Bologna.[15] The Jesuit order, created during the Reformation, contributed a number of distinguished medical scientists. In the field of bacteriology it was the Jesuit Athanasius Kircher (1671) who first proposed that living beings enter and exist in the blood (a precursor of germ theory. In the development of opthalmology, Christophe Scheiner made important advances in relation to refraction of light and the retinal image.[8] Gregor Mendel, an Austrian scientist and Augustinian friar, began experimenting with peas around 1856. Observing the processes of pollination at his monastery in modern Czechoslovakia, Mendel studied and developed theories pertaining to the field of science now called genetics. Mendel published his results in 1866 in the Journal of the Brno Natural History Society. He is considered the father of modern genetics.[16]

Catholic religious institutes, notably those for women developed many hospitals throughout Europe and its empires. Ancient orders like the Dominicans and Carmelites have long lived in religious communities that work in ministries such as education and care of the sick.[17] The Portuguese Saint John of God (d. 1550) founded the Brothers Hospitallers of St. John of God to care for the sick and afflicted. The order built hospitals across Europe and its growing Empires. In 1898, John was declared patron of the dying and all hospitals by Pope Leo XIII.[18] in The Italian Saint Camillus de Lellis, considered a patron saint of nurses, was a reformed gambler and soldier who became a nurse and then director of Hospital for Incurables[disambiguation needed] in Rome. In 1584 he founded the Camillians to tend to the plague-stricken.[19] Irishwoman Catherine McAuley founded the Sisters of Mercy in Dublin in 1831. Her congregation went on to found schools and hospitals across the globe.[20] Saint Jeanne Jugan founded the Little Sisters of the Poor on the Rule of Saint Augustine to assist the impoverished elderly of the streets of France in the mid-nineteenth century. It too spread around the world.[21]

The Americas

The Spanish and Portuguese Empires were largely responsible for spreading Catholic to South and Central America, where the church established substantial hospital networks.

Catholic hospitals were established in the modern United States prior to the American War of Independence. The first was probably Charity Hospital, New Orleans, established around 1727.[22] The Sisters of Saint Francis of Syracuse, New York, produced Saint Marianne Cope, who opened and operated some of the first general hospitals in the United States, instituting cleanliness standards which influenced the development of America's modern hospital system, and famously taking her nuns to Hawaii to work with Saint Damien of Molokai in the care of lepers. St Damien himself is considered a martyr of charity and model of Catholic humanitarianism for his mission to the lepers of Molokai.

The Catholic Church has is the largest private provider of health care in the United States of America.[23] During the 1990s, the church provided about one in six hospital beds in America, at around 566 hospitals, many established by nuns.[24] The church has carried a disproportionate number of poor and uninsured patients at its facilities and the American bishops first called for universal health care in America in 1919. The church has been an active campaigner in that cause ever since.[25] In the abortion debate in America, the church has sought to retain the right not to perform abortions in its health care facilities.[26] In 2012, the church operated 12.6% of hospitals in the USA, accounting for 15.6% of all admissions, and around 14.5% of hospital expenses (c. 98.6 billion dollars). Compared to the public system, the church provided greater financial assistance or free care to poor patients, and was a leading provider of various low-profit health services such as breast cancer screenings, nutrition programs, trauma, and care of the elderly.[27]

Asia

During the Middle Ages, Arab medicine was influential on Europe. During Europe's Age of Discovery, Catholic missionaries, notably the Jesuits, introduced the modern sciences to India, China and Japan. While persecutions continue to limit the spread of Catholic institutions to Middle Eastern Muslim nations, and such places as Communist China and North Korea, elsewhere in Asia the church is a major provider of health care services - especially in Catholic Nations like the Phillipines.

The famous Mother Teresa of Calcutta established the Missionaries of Charity in the slums of Calcutta in 1948 to work among "the poorest of the poor". Initially founding a school, she then gathered other sisters who "rescued new-born babies abandoned on rubbish heaps; they sought out the sick; they took in lepers, the unemployed, and the mentally ill". Teresa achieved fame in the 1960s and began to establish convents around the world. By the time of her death in 1997, the religious institute she founded had more than 450 centres in over 100 countries.[28]

Oceania

French, Portuguese, British and Irish missionaries brought Catholicism to Oceania and built hospitals and care centres across the region. The church remains not only a key provider of health care in predominantly Catholic nations like East Timor but also in predominantly Protestant and secular nations like Australia and New Zealand.

As restrictions were lifted by British authorities on the practice of Catholicism in colonial Australia, Catholic religious institutes founded many of Australia's hospitals. Irish Sisters of Charity arrived in Sydney in 1838 and established St Vincent's Hospital, Sydney in 1857 as a free hospital for the poor. The Sisters went on to found hospitals, hospices, research institutes and aged care facilities in Victoria, Queensland and Tasmania.[29] At St Vincent's they trained leading surgeon Victor Chang and opened Australia's first AIDS clinic.[30] In the 21st century, with more and more lay people involved in management, the sisters began callaborating with Sisters of Mercy Hospitals in Melbourne and Sydney. Jointly the group operates four public hospitals; seven private hospitals and 10 aged care facilities.

The Sisters of Mercy arrived in Auckland in 1850 and were the first order of religious sisters to come to New Zealand and began work in health care and education.[31]

The Sisters of St Joseph, founded in Australia by Australia's first Saint, Mary MacKillop, and Fr Julian Tenison Woods in 1867.[32][33][34] MacKillop travelled throughout Australasia and established schools, convents and charitable institutions.[35] The English Sisters of the Little Company of Mary arrived in 1885 and have since established public and private hospitals, retirement living and residential aged care, community care and comprehensive palliative care in New South Wales, the ACT, Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia and the Northern Territory.[36] The Little Sisters of the Poor, who follow the charism of Saint Jeanne Jugan to "offer hospitality to the needy aged" arrived in Melbourne in 1884 and now operate four aged care homes in Australia.[37]

Catholic Health Australia is today the largest non-government provider grouping of health, community and aged care services in Australia. These do not operate for profit and range across the full spectrum of health services, representing about 10% of the health sector and employing 35,000 people.[38] Catholic organisations in New Zealand remain heavily involved in community activities including education; health services; chaplaincy to prisons, rest homes, and hospitals; social justice and human rights advocacy.[39][40]

Africa

Catholicism has grown rapidly in Africa over the last two centuries. As in all other continents, Catholic missionaries established health care centres across the continent - though limitations on Catholic institutions remain in place for much of Muslim North Africa.

In Africa today, the church is heavily engaged in providing care to AIDS sufferers amidst the AIDS epidemic. Much of the Church's AIDS effort is concentrated in developing nations - in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.[41] According to PBS news, in 2011, there were "117,000 Catholic medical facilities, from clinics in the deepest jungle to large urban hospitals in the developing world, that are involved in treating both people that are already infected with AIDS and trying to prevent the transmission to at-risk populations".[42] Catholic prohibition on the use of condoms has been highly controversial in light of the AIDS crisis. In 2010, Pope Benedict XVI characterised condom use as not a "real or moral solution" to the spread of AIDS, but potentially a "first step" in the direction of moralisation and responsibility, when used with "the intention of reducing the risk of infection". Issues therefore emerge as to collaboration with secular organizations such as UNAIDS and the World Health Organization in the provision of AIDS care and prevention education. Catholic organisations like Caritas are heavily engaged in the provision of AIDS care in Developing Nations.

Religious orders dedicated to care giving

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2013) |

In keeping with the emphasis of Catholic social teaching, many religious institutes have devoted themselves to service of the sick, homeless, disabled, orphaned, aged or mentally ill. Women's religious institutes played a particularly prominent role in the development of the Catholic Church's health care networks.

Contemporary issues

Bioethics

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2013) |

The moral teachings of the Catholic Church raise questions as to the provision of certain health procedures at Catholic health facilities. Areas of controversy include euthanasia and abortion, which are legal in various jurisdictions but which the church outright opposes; and IVF and surrogacy, to which the church is currently formulating responses to new technologies. In public debates, particularly among Western nations like the United States, this has raised questions over insurance public/private financial co-operation and government interference and regulation of health facilities. Writing in 2012, the Australian human rights lawyer and Jesuit Frank Brennan, in response to calls for public funding to Catholic hospitals to be contingent on them offering the "full suites of services", said that:[43]

The nation is the better for policies and funding arrangements that encourage public and private providers of healthcare, including the Churches. The public may need to be patient with Church authorities as they discern appropriate moral responses to new technologies. This is a small price to pay for creative diversity which delivers healthcare of the highest standard with a special character cherished by many citizens, not just Catholics.

In the United States, a similar debate saw some conservative Church leaders denounce the Obama Administration's plan to force faith-based hospitals, welfare organisations and schools to provide birth control and reproductive services in health insurance plans in a major election year controversy in 2012.[44]

Patron Saints

Physicians

There are a number of patron saints for physicians, the most important of whom are Saint Luke the Evangelist the physician and disciple of Christ, Saints Cosmas and Damian (3rd-century physicians from Syria), and Saint Pantaleon (4th-century physician from Nicomedia). Archangel Raphael is also considered a patron saint of physicians.[45]

Surgeons

The patron saints for surgeons are Saint Luke the Evangelist, the physician and disciple of Christ, Saints Cosmas and Damian (3rd-century physicians from Syria), Saint Quentin (3rd-century saint from France), Saint Foillan (7th-century saint from Ireland), and Saint Roch (14th-century saint from France).[46]

Nurses

Various Catholic Saints are considered patrons of nursing: Saint Agatha, Saint Alexius, Saint Camillus of Lellis, St Catherine of Alexandria, St Catherine of Siena, St John of God, St Margaret of Antioch, and Raphael the Archangel.[47]

See also

- Catholic social teaching

- Catholic Church and AIDS

- Role of the Catholic Church in Western civilization

- Catholic Health Association of the United States

- Pontifical Council for the Pastoral Care of Health Care Workers

- Catholic Health Australia

- Medicine

- Philosophy of healthcare

- Islamic medicine

- Chinese medicine

References

- ^ Agnew, John (12 February 2010). "Deus Vult: The Geopolitics of Catholic Church". Geopolitics. 15 (1): 39–61. doi:10.1080/14650040903420388.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Catholic hospitals comprise one quarter of world's healthcare, council reports :: Catholic News Agency (CNA)". Catholic News Agency. 10 February 2010. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ a b c d e Geoffrey Blainey; A Short History of Christianity; Penguin Viking; 2011

- ^ a b c d e http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07480a.htm

- ^ http://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/pontifical_councils/hlthwork/documents/XXVIIConferenzaPCPS.pdf

- ^ http://saints.sqpn.com/saint-cosmas/

- ^ http://saints.sqpn.com/saint-luke-the-evangelist/

- ^ a b c d e f http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/10122a.htm

- ^ http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11447a.htm

- ^ Geoffrey Blainey; A Short History of Christianity; Penguin Viking; 2011; pp 214-215.

- ^ http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07477a.htm

- ^ Maddocks, Fiona. Hildegard of Bingen: The Woman of Her Age (New York: Doubleday, 2001), 155.

- ^ http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/13100c.htm

- ^ http://edition.cnn.com/2012/10/20/health/saint-marianne-cope/index.html?hpt=hp_t3

- ^ http://www.catholicherald.co.uk/features/2011/05/06/what-the-church-has-given-the-world/

- ^ Jacob Bronowski; The Ascent of Man; Angus & Robertson, 1973 ISBN 0-563-17064-6

- ^ http://curia.op.org/en/index.php/eng/about-us/sisters

- ^ http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02802b.htm

- ^ http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03217b.htm

- ^ http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/10199a.htm

- ^ http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Catholic_Encyclopedia_(1913)/Little_Sisters_of_the_Poor

- ^ http://www.nytimes.com/1994/08/25/us/health-care-debate-catholic-church-catholic-leaders-dilemma-abortion-vs.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm

- ^ The Health Care Debate: The Catholic Church; Catholic Leaders' Dilema: Abortion vs. Universal Care; by Gustav Niebuhr, New York Times, 25 August 1994.

- ^ http://www.nytimes.com/1994/08/25/us/health-care-debate-catholic-church-catholic-leaders-dilemma-abortion-vs.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm

- ^ http://www.nytimes.com/1994/08/25/us/health-care-debate-catholic-church-catholic-leaders-dilemma-abortion-vs.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm

- ^ http://www.nytimes.com/1994/08/25/us/health-care-debate-catholic-church-catholic-leaders-dilemma-abortion-vs.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm

- ^ http://www.thefiscaltimes.com/Columns/2012/03/01/Obama-Risks-$100-Billion-if-Catholic-Hospitals-Close.aspx#duHJcO1ezw65J8s8.99

- ^ "Mother Teresa". The Daily Telegraph. London. 6 September 1997.

- ^ "Internet Archive Wayback Machine". Web.archive.org. 6 July 2011. Retrieved 2012-07-31.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses generic title (help) - ^ "St Vincent's Hospital, history and tradition, sesquicentenary – sth.stvincents.com.au". Exwwwsvh.stvincents.com.au. Retrieved 2012-07-31.

- ^ "Sisters of Mercy New Zealand". Sisters of Mercy New Zealand. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ^ "Internet Archive Wayback Machine". Web.archive.org. 16 July 2011. Retrieved 2012-07-31.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses generic title (help) - ^ "Internet Archive Wayback Machine". Web.archive.org. 6 July 2011. Retrieved 2012-07-31.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses generic title (help) - ^ "Internet Archive Wayback Machine". Web.archive.org. 6 July 2011. Retrieved 2012-07-31.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses generic title (help) - ^ Thorpe, Osmund. "Biography – Mary Helen MacKillop – Australian Dictionary of Biography". Adbonline.anu.edu.au. Retrieved 2012-07-31.

- ^ http://www.lcmhealthcare.org.au/

- ^ "Little Sisters of the Poor Oceania". Littlesistersofthepoor.org.au. Retrieved 2012-07-31.

- ^ http://www.cha.org.au/site.php?id=24

- ^ "Catholic Church in NZ: Living Justly". New Zealand Catholic Bishops' Conference. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ^ "Sisters Of St Joseph - The Journey". Sisters of St Joseph Whanganui. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ^ http://journalism.nyu.edu/publishing/archives/pavement/city/aids-and-the-catholic-church/index.html

- ^ http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/health/jan-june11/vatican_05-27.html

- ^ http://www.eurekastreet.com.au/article.aspx?aeid=33476

- ^ http://abcnews.go.com/blogs/politics/2012/01/catholic-church-vs-obama-in-election-year-showdown/

- ^ http://saints.sqpn.com/patrons-of-physicians/

- ^ http://saints.sqpn.com/patrons-of-surgeons/

- ^ http://saints.sqpn.com/patrons-of-nurses/#sthash.ZnjS7ueq.dpuf