Langerhans cell histiocytosis

| Langerhans cell histiocytosis | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Oncology |

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare disease involving clonal proliferation of Langerhans cells, abnormal cells deriving from bone marrow and capable of migrating from skin to lymph nodes. Clinically, its manifestations range from isolated bone lesions to multisystem disease.

LCH is part of a group of clinical syndromes called histiocytoses, which are characterized by an abnormal proliferation of histiocytes (an archaic term for activated dendritic cells and macrophages). These diseases are related to other forms of abnormal proliferation of white blood cells, such as leukemias and lymphomas.

The disease has gone by several names, including Hand–Schüller–Christian disease, Abt-Letterer-Siwe disease, and Histiocytosis X, until it was renamed in 1985 by the Histiocyte Society.[1]

Classification

| Alternative names |

|---|

| Histiocytosis X

Histiocytosis X syndrome |

| Subordinate terms |

| Hand-Schüller-Christian disease

Letterer-Siwe disease |

The disease spectrum results from clonal accumulation and proliferation of cells resembling the epidermal dendritic cells called Langerhans cells, hence sometimes called Dendritic Cell Histiocytosis. These cells in combination with lymphocytes, eosinophils, and normal histiocytes form typical LCH lesions that can be found in almost any organ.[2] A similar set of diseases has been described in Canine histiocytic diseases.

LCH is clinically divided into three groups: unifocal, multifocal unisystem, and multifocal multisystem.[3]

- Unifocal

- Unifocal LCH, also called Eosinophilic Granuloma (an older term which is now known to be a misnomer), is a slowly-progressing disease characterized by an expanding proliferation of Langerhans Cells in various bones. It is a monostotic or polystotic disease with no extraskeletal involvement. This differentiates Eosinophilic Granuloma from other forms of Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (Letterer-Siwe or Hand-Schüller-Christian variant.[4]

- Multifocal unisystem

- Seen mostly in children, multifocal unisystem LCH is characterized by fever, bone lesions and diffuse eruptions, usually on the scalp and in the ear canals. 50% of cases involve the pituitary stalk, leading to diabetes insipidus. The triad of diabetes insipidus, exopthalmos, and lytic bone lesions is known as the Hand-Schüller-Christian triad. Peak onset is 2-10 years of age.

- Multifocal multisystem

- Multifocal multisystem LCH, also called Letterer-Siwe disease, is a rapidly-progressing disease in which Langerhans Cell cells proliferate in many tissues. It is mostly seen in children under age 2, and the prognosis is poor: even with aggressive chemotherapy, the 5-year survival is only 50%.[5]

Pulmonary Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (PLCH) is a unique form of LCH in that it occurs almost exclusively in cigarette smokers. It is now considered a form of smoking-related interstitial lung disease. Some patients recover completely after they stop smoking, but others develop long-term complications such as pulmonary fibrosis and pulmonary hypertension.Pulmonary Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (PLCH) is a unique form of LCH in that it occurs almost exclusively in cigarette smokers. It is now considered a form of smoking-related interstitial lung disease. Some patients recover completely after they stop smoking, but others develop long-term complications such as pulmonary fibrosis and pulmonary hypertension.[citation needed]

Prevalence

LCH usually affects children between 1 and 15 years old, with a peak incidence between 5 and 10 years of age. Among children under the age of 10, yearly incidence is thought to be 1 in 200,000;[6] and in adults even rarer, in about 1 in 560,000.[7] It has been reported in elderly but is vanishingly rare.[8] It is most prevalent in Caucasians, and affects males twice as often as females.[citation needed]

LCH is usually a sporadic and non-hereditary condition but familial clustering has been noted in limited number of cases. Hashimoto-Pritzker disease is a congenital self-healing variant of Hand-Schüller-Christian disease.[9]

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH) is a matter of debate. There are ongoing investigations to determine whether LCH is a reactive or neoplastic process. Arguments supporting the reactive nature of LCH include the occurrence of spontaneous remissions, the extensive secretion of multiple cytokines by dendritic cells and bystander-cells (a phenomenon known as cytokine storm) in the lesional tissue, favorable prognosis and relatively good survival rate in patients without organ dysfunction or risk organ involvement.[10][11]

On the other hand, the infiltration of organs by monoclonal population of pathologic cells, and the successful treatment of subset of disseminated disease using chemotherapeutic regimens are all consistent with a neoplastic process.[12][13][14] In addition, a demonstration, using X chromosome–linked DNA probes, of LCH as a monoclonal proliferation provided additional support for the neoplastic origin of this disease.[15] While clonality is an important attribute of cancer, its presence does not prove that a proliferative process is neoplastic. Recurrent cytogenetic or genomic abnormalities would also be required to demonstrate convincingly that LCH is a malignancy.

Activating mutation of a protooncogen in the Raf family, the BRAF gene, was detected in 35 of 61 (57%) LCH biopsy samples with mutations being more common in patients younger than 10 years (76%) than in patients aged 10 years and older (44%).[16] This study documented the first recurrent mutation in LCH samples. Two independent studies have confirmed this finding.[17][18] Presence of this activating mutation could support the notion to characterize LCH as myelodysplastic disorder.

Signs and symptoms

LCH provokes a non-specific inflammatory response, which includes fever, lethargy, and weight loss. Organ involvement can also cause more specific symptoms.

- Bone: The most-frequently seen symptom in both unifocal and multifocal disease is painful bone swelling. The skull is most frequently affected, followed by the long bones of the upper extremities and flat bones. Infiltration in hands and feet is unusual. Osteolytic lesions can lead to pathological fractures.

- Skin: Commonly seen are a rash which varies from scaly erythematous lesions to red papules pronounced in intertriginous areas. Up to 80% of LCH patients have extensive eruptions on the scalp.

- Bone marrow: Pancytopenia with superadded infection usually implies a poor prognosis. Anemia can be due to a number of factors and does not necessarily imply bone marrow infiltration.

- Lymph node: Enlargement of the liver in 20%, spleen in 30% and lymph nodes in 50% of Histiocytosis cases.[19]

- Endocrine glands: Hypothalamic pituitary axis commonly involved. Diabetes insipidus is most common. Anterior pituitary hormone deficiency is usually permanent.

- Lungs: some patients are asymptomatic, diagnosed incidentally because of lung nodules on radiographs; others suffer from chronic cough and shortness of breath.

- Less frequently gastrointestinal tract and central nervous system.

Diagnosis

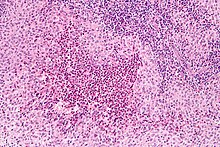

Diagnosis is confirmed histologically by tissue biopsy. Hematoxylin-eosin stain of biopsy slide will show features of Langerhans Cell e.g. distinct cell margin, pink granular cytoplasm. Presence of Birbeck granules on electron microscopy and immuno-cytochemical features e. g. CD1 positivity are more specific. Initially routine blood tests e.g. full blood count, liver function test, U&Es, bone profile are done to determine disease extent and rule out other causes. Radiology will show osteolytic bone lesions and damage to the lung. The latter may be evident in chest X-rays with micronodular and interstitial infiltrate in the mid and lower zone of lung, with sparing of the Costophrenic angle or honeycomb appearance in older lesions. MRI and CT may show infiltration in sella turcica. Assessment of endocrine function and bonemarrow biopsy are also performed when indicated.

- S-100 protein is expressed in a cytoplasmic pattern

- peanut agglutinin (PNA) is expressed on the cell surface and perinuclearly

- major histocompatibility (MHC) class II is expressed (because histiocytes are macrophages)

- CD1a

- langerin (CD207), a Langerhans Cell–restricted protein that induces the formation of Birbeck granules and is constitutively associated with them, is a highly specific marker.[20]

Treatment

Treatment is guided by extent of disease. Solitary bone lesion may be amenable through excision or limited radiation, dosage of 5-10 Gys for children, 24-30 Gys for adults. However systemic diseases often require chemotherapy. Use of systemic steroid is common, singly or adjunct to chemotherapy. Local steroid cream is applied to skin lesions. Endocrine deficiency often require lifelong supplement e.g. desmopressin for diabetes insipidus which can be applied as nasal drop. Chemotherapeutic agents such as alkylating agents, antimetabolites, vinca alkaloids either singly or in combination can lead to complete remission in diffuse disease.

Prognosis

Excellent for single-focus disease. With multi-focal disease 60% have a chronic course, 30% achieve remission and mortality is up to 10%.[21]

Pop Culture

In the 10th episode of season 3 of House entitled "Merry Little Christmas", the primary patient is a girl with dwarfism who has a variety of symptoms, who is ultimately diagnosed with Langerhans cell histiocytosis.[22]

See also

References

- ^ "Histiocytosis syndromes in children. Writing Group of the Histiocyte Society". Lancet. 1 (8526): 208–9. 1987. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)95528-5. PMID 2880029.

- ^ Makras P, Papadogias D, Kontogeorgos G, Piaditis G, Kaltsas G (2005). "Spontaneous gonadotrophin deficiency recovery in an adult patient with Langerhans cell Histiocytosis (LCH)". Pituitary. 8 (2): 169–74. doi:10.1007/s11102-005-4537-z. PMID 16379033.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cotran, Ramzi S.; Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson; Robbins, Stanley L. (2005). Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease. St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Saunders. pp. 701-. ISBN 0-8089-2302-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Template:See chapter 501 in Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics 18th ed. Question 45 same chapter

- ^ http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1100579-overview

- ^ "MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia: Histiocytosis". Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- ^ "Histiocytosis Association of Canada". Retrieved 2007-05-16.

- ^ Gerlach B, Stein A, Fischer R, Wozel G, Dittert D, Richter G (1998). "[Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis in the elderly]". Der Hautarzt; Zeitschrift für Dermatologie, Venerologie, und verwandte Gebiete (in German). 49 (1): 23–30. doi:10.1007/s001050050696. PMID 9522189.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kapur P, Erickson C, Rakheja D, Carder K, Hoang M (2007). "Congenital self-healing reticuloHistiocytosis (Hashimoto-Pritzker disease): ten-year experience at Dallas Children's Medical Center". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 56 (2): 290–4. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.09.001. PMID 17224372.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Broadbent, V. (31 January 1984). "Spontaneous Remission of Multi-System Histiocytosis X". The Lancet. 323 (8371): 253–254. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(84)90127-2. PMID 6142997.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Filippi, Paola De (1 March 2006). "Specific polymorphisms of cytokine genes are associated with different risks to develop single-system or multi-system childhood Langerhans cell histiocytosis". British Journal of Haematology. 132 (6): 784–787. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05922.x. PMID 16487180.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Steen, A.E. (1 July 2001). "Successful treatment of cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis with low-dose methotrexate". British Journal of Dermatology. 145 (1): 137–140. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04298.x. PMID 11453923.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Allen, Carl E. (1 March 2010). "Neurodegenerative central nervous system Langerhans cell histiocytosis and coincident hydrocephalus treated with vincristine/cytosine arabinoside". Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 54 (3): 416–423. doi:10.1002/pbc.22326. PMC 3444163. PMID 19908293.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Minkov, M. (1 November 1999). "Cyclosporine A therapy for multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis". Medical and Pediatric Oncology. 33 (5): 482–485. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-911X(199911)33:5<482::AID-MPO8>3.0.CO;2-Y. PMID 10531573.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Willman, Cheryl L. (21 July 1994). "Langerhans'-Cell Histiocytosis (Histiocytosis X) -- A Clonal Proliferative Disease". New England Journal of Medicine. 331 (3): 154–160. doi:10.1056/NEJM199407213310303. PMID 8008029.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Badalian-Very, G. (2 June 2010). "Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis". Blood. 116 (11): 1919–1923. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-04-279083. PMC 3173987. PMID 20519626.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Satoh, Takeshi (9 April 2012). "B-RAF Mutant Alleles Associated with Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis, a Granulomatous Pediatric Disease". PLoS ONE. 7 (4): e33891. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0033891. PMC 3323620. PMID 22506009.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Peters, Tricia L (10). "1372 Frequent BRAF V600E Mutations Are Identified in CD207+ Cells in LCH Lesions, but BRAF Status does not Correlate with Clinical Presentation of Patients or Transcriptional Profiles of CD207+ Cells".

Oral and Poster Abstracts presented at 53rd ASH Annual Meeting and Exposition

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis - Patient UK". Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- ^ Valladeau, Jenny (31 December 1999). "Langerin, a Novel C-Type Lectin Specific to Langerhans Cells, Is an Endocytic Receptor that Induces the Formation of Birbeck Granules". Immunity. 12 (1): 71–81. doi:10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80160-0. PMID 10661407.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Komp D, El Mahdi A, Starling K, Easley J, Vietti T, Berry D, George S (1980). "Quality of survival in Histiocytosis X: a Southwest Oncology Group study". Med. Pediatr. Oncol. 8 (1): 35–40. doi:10.1002/mpo.2950080106. PMID 6969347.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/House_(season_3)

External links

- EuroHistioNet (EHN) a EU network granted by the EU commission with a multilanguage web site

- Images of LCH MedPix(r)Database

- Histiocyte Society An International Community Dedicated to Research and Treatment

- Seven Part Video Series

- Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis, article by the Sydney Children's Hospital

- 5-Minute Clinical Consult

- synd/2224 at Who Named It?

- [1] The Histiocytosis Association is an organization dedicated to helping diagnosed patients find trained doctors in their area, raising awareness, finding local emotional support, and assisting interested people in finding more information.