Klinefelter syndrome

| Klinefelter syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

Klinefelter syndrome or Klinefelter's syndrome is the set of symptoms resulting from additional X genetic material in males. Also known as 47,XXY or XXY, Klinefelter syndrome is a genetic disorder in which there is at least one extra X chromosome to a standard human male karyotype, for a total of 47 chromosomes rather than the 46 found in genetically typical humans.[1] While females have an XX chromosomal makeup, and males an XY, individuals with Klinefelter syndrome have at least two X chromosomes and at least one Y chromosome.[2] Because of the extra chromosome, individuals with the condition are usually referred to as "XXY males", or "47,XXY males".[3]

This chromosome constitution (karyotype) exists in roughly between 1:500 to 1:1000 live male births[4][5][note 1] but many of these people may not show symptoms. If the physical traits associated with the syndrome become apparent, they normally appear after the onset of puberty.[10]

In humans, 47,XXY is the most common sex chromosome aneuploidy in males[11] and the second most common condition caused by the presence of extra chromosomes. Other mammals also have the XXY syndrome, including mice.[12]

Principal effects include hypogonadism and sterility. A variety of other physical and behavioural differences and problems are common, though severity varies and many XXY boys have few detectable symptoms.

Signs and symptoms

There are many variances within the XXY population, just as within the 46,XY population. While it is possible to characterise XXY males with certain body types and physical characteristics, that in itself should not be the method of identification as to whether or not someone has XXY. The only reliable method of identification is karyotype testing. The degree to which XXY males are affected, both physically and developmentally, differs widely from person to person.

Physical

As babies and children, XXY males may have weaker muscles and reduced strength. As they grow older, they tend to become taller than average. They may have less muscle control and coordination than other boys their age.[4]

During puberty, the physical traits of the syndrome become more evident; because these boys do not produce as much testosterone as other boys, they have a less muscular body, less facial and body hair, and broader hips. As teens, XXY males may have larger breasts, weaker bones, and a lower energy level than other boys.[4]

By adulthood, XXY males look similar to males without the condition, although they are often taller. In adults, possible characteristics vary widely and include little to no signs of affectedness, a lanky, youthful build and facial appearance, or a rounded body type with some degree of gynecomastia (increased breast tissue).[13] Gynecomastia is present to some extent in about a third of affected individuals, a slightly higher percentage than in the XY population. About 10% of XXY males have gynecomastia noticeable enough that they may choose to have cosmetic surgery.[3]

Affected males are often infertile, or may have reduced fertility. Advanced reproductive assistance is sometimes possible.[14]

The term hypogonadism in XXY symptoms is often misinterpreted to mean "small testicles" or "small penis". In fact, it means decreased testicular hormone/endocrine function. Because of this (primary) hypogonadism, individuals will often have a low serum testosterone level but high serum follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) levels.[15] Despite this misunderstanding of the term, however, it is true that XXY men may also have microorchidism (i.e., small testicles).[15]

XXY males are also more likely than other men to have certain health problems, which typically affect females, such as autoimmune disorders, breast cancer, venous thromboembolic disease, and osteoporosis.[4][16] In contrast to these potentially increased risks, it is currently thought that rare X-linked recessive conditions occur less frequently in XXY males than in normal XY males, since these conditions are transmitted by genes on the X chromosome, and people with two X chromosomes are typically only carriers rather than affected by these X-linked recessive conditions.

Cognitive and developmental

Some degree of language learning or reading impairment may be present,[17] and neuropsychological testing often reveals deficits in executive functions, although these deficits can often be overcome through early intervention.[18] There may also be delays in motor development which can be addressed through occupational therapy and physical therapy.[19] XXY males may sit up, crawl, and walk later than other infants; they may also struggle in school, both academically and with sports.[4]

Cause

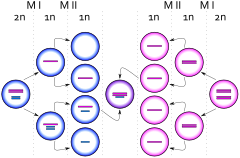

The extra X chromosome is retained because of a nondisjunction event during meiosis I (gametogenesis). Nondisjunction occurs when homologous chromosomes, in this case the X and Y sex chromosomes, fail to separate, producing a sperm with an X and a Y chromosome. Fertilizing a normal (X) egg produces an XXY offspring. The XXY chromosome arrangement is one of the most common genetic variations from the XY karyotype, occurring in about 1 in 500 live male births.[4]

Another mechanism for retaining the extra X chromosome is through a nondisjunction event during meiosis II in the female. Nondisjunction will occur when sister chromatids on the sex chromosome, in this case an X and an X, fail to separate. (meiosis) An XX egg is produced which, when fertilized with a Y sperm, yields XXY offspring.

In mammals with more than one X chromosome, the genes on all but one X chromosome are not expressed; this is known as X inactivation. This happens in XXY males as well as normal XX females.[20] However, in XXY males, a few genes located in the pseudoautosomal regions of their X chromosomes, have corresponding genes on their Y chromosome and are capable of being expressed.[21]

The first published report of a man with a 47,XXY karyotype was by Patricia Jacobs and John Strong at Western General Hospital in Edinburgh, Scotland in 1959.[22] This karyotype was found in a 24-year-old man who had signs of Klinefelter syndrome. Jacobs described her discovery of this first reported human or mammalian chromosome aneuploidy in her 1981 William Allan Memorial Award address.[23]

Variations

48,XXYY and 48,XXXY occur in 1 in 18,000–50,000 male births. The incidence of 49,XXXXY is 1 in 85,000 to 100,000 male births.[24] These variations are extremely rare. Additional chromosomal material can contribute to cardiac, neurological, orthopedic and other anomalies.

Males with Klinefelter syndrome may have a mosaic 47,XXY/46,XY constitutional karyotype and varying degrees of spermatogenic failure. Mosaicism 47,XXY/46,XX with clinical features suggestive of Klinefelter syndrome is very rare. Thus far, only about 10 cases have been described in literature.[25]

Analogous XXY syndromes are known to occur in cats—specifically, the presence of calico or tortoiseshell markings in male cats is an indicator of the relevant abnormal karyotype. As such, male cats with calico or tortoiseshell markings are a model organism for Klinefelter syndrome.[26]

Diagnosis

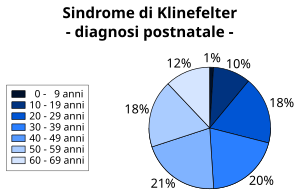

About 10% of Klinefelter cases are found by prenatal diagnosis.[28] The first clinical features may appear in early childhood or, more frequently, during puberty, such as lack of secondary sexual characters and aspermatogenesis,[29] while tall stature as a symptom can be hard to diagnose during puberty. Despite the presence of small testes, only a quarter of the affected males are recognized as having Klinefelter syndrome at puberty[30][31] and 25% received their diagnosis in late adulthood: about 64% affected individuals are not recognized as such.[32] Often the diagnosis is made accidentally as a result of examinations and medical visits for reasons not linked to the condition.[33]

The standard diagnostic method is the analysis of the chromosomes' karyotype on lymphocytes. In the past, the observation of the Barr body was common practice as well.[31] To confirm mosaicism, it is also possible to analyze the karyotype using dermal fibroblasts or testicular tissue.[34]

Other methods may be: research of high serum levels of gonadotropins (follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone), presence of azoospermia, determination of the sex chromatin,[35] and prenatally via chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis. A 2002 literature review of elective abortion rates found that approximately 58% of pregnancies in the United States with a diagnosis of Klinefelter syndrome were terminated.[36]

Differential diagnosis

The symptoms of Klinefelter syndrome are often variable; therefore, a karyotype analysis should be ordered when small testes, infertility, gynecomastia, long legs/arms, developmental delay, speech/language deficits, learning disabilities/academic issues and/or behavioral issues are present in an individual.[1] The differential diagnosis for the Klinefelter syndrome can include the following conditions: fragile X syndrome, Kallmann syndrome and Marfan syndrome. The cause of hypogonadism can be attributed to many other different medical conditions.

There have been some reports of individuals with Klinefelter syndrome who also have other chromosome abnormalities, such as Down syndrome.[37]

Treatment

The genetic variation is irreversible. Often individuals that have noticeable breast tissue or hypogonadism experience depression and/or social anxiety because they are outside of social norms. This is academically referred to as psychosocial morbidity.[38] At least one study indicates that planned and timed support should be provided for young men with Klinefelter syndrome to ameliorate current poor psychosocial outcomes.[38]

By 2010 over 100 successful pregnancies have been reported using IVF technology with surgically removed sperm material from males with Klinefelter syndrome.[39]

Prognosis

Children with XXY differ little from other children. Although they can face problems during adolescence, often emotional and behavioural, and difficulties at school, most of them can achieve full independence from their families in adulthood. Most can lead a normal, healthy life.

The results of a study carried out on 87 Australian adults with the syndrome shows that those who have had a diagnosis and appropriate treatment from a very young age had a significant benefit with respect to those who had been diagnosed in adulthood.[40]

There is research suggesting Klinefelter syndrome substantially decreases life expectancy among affected individuals, though the evidence is not definitive.[41] A 1985 publication identified a greater mortality mainly due to diseases of the aortic valve, development of tumors and possible subarachnoid hemorrhages, reducing life expectancy by about 5 years.[42] Later studies have reduced this estimated reduction to an average of 2.1 years.[43] These results are still questioned data, are not absolute, and will need further testing.[41]

Epidemiology

This syndrome, evenly spread in all ethnic groups, has a prevalence of 1-2 subjects every 1000 males in the general population.[30][44][45][46] 3.1% of infertile males have Klinefelter syndrome. The syndrome is also the main cause of male hypogonadism.[47]

According to a meta-analysis, the prevalence of the syndrome has increased over the past decades; however, this does not appear to be correlated with the increase of the age of the mother at conception, as no increase was observed in the prevalence of other trisomies of sex chromosomes (XXX and XYY).[48]

History

The syndrome was named after Harry Klinefelter, who, in 1942, worked with Fuller Albright at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts and first described it in the same year.[13][29] The account given by Klinefelter came to be known as Klinefelter syndrome as his name appeared first on the published paper, and seminiferous tubule dysgenesis was no longer used.

See also

- Aneuploidy

- Intersex

- Mosaic (genetics)

- True hermaphroditism

- Turner Syndrome

- XXYY syndrome

- Non-Klinefelter XXY

Notes

References

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17062147 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 17062147instead. - ^ Cotran, Ramzi S.; Kumar, Vinay; Fausto, Nelson; Nelso Fausto; Robbins, Stanley L.; Abbas, Abul K. (2005). Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease. St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Saunders. p. 179. ISBN 0-7216-0187-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Bock, Robert (August 1993). "Understanding Klinefelter Syndrome: A Guide for XXY Males and their Families". NIH Pub. No. 93-3202. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Retrieved 2007-04-07.

- ^ a b c d e f "Klinefelter Syndrome". Health Information. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 2007-02-19. Retrieved 2012-11-02. Cite error: The named reference "NICHD" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Klinefelter syndrome". Genetics Home Reference. National Library of Medicine. 2012-10-30. Retrieved 2012-11-02.

- ^ Saavedra-Castillo E, Cortés-Gutiérrez EI, Dávila-Rodríguez MI, Reyes-Martínez ME, Oliveros-Rodríguez A (February 2005). "47,XXY female with testicular feminization and positive SRY: a case report". J Reprod Med. 50 (2): 138–40. PMID 15755052.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Thangaraj K, Gupta NJ, Chakravarty B, Singh L (October 1998). "A 47,XXY female". Lancet. 352 (9134): 1121. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)79762-2. PMID 9798596.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schmid M, Guttenbach M, Enders H, Terruhn V (December 1992). "A 47,XXY female with unusual genitalia". Hum. Genet. 90 (4): 346–9. doi:10.1007/BF00220456. PMID 1483688.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Röttger S, Schiebel K, Senger G, Ebner S, Schempp W, Scherer G (2000). "An SRY-negative 47,XXY mother and daughter". Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 91 (1–4): 204–7. doi:10.1159/000056845. PMID 11173857.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kronenberg, HM (2007). Williams Textbook of Endocrinology (11 ed.). Saunders. ISBN 1416029117.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ William, J (2005). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology (10 ed.). Saunders. p. 549. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Russell, Liane Brauch (9 June 1961). "Genetics of Mammalian Sex Chromosomes MOUSE STUDIES THROW LIGHT ON THE FUNCTIONS AND ON THE OCCASIONALLY ABERRANT BEHAVIOR OF SEX CHROMOSOMES". Science. 133 (3467): 1795–1803. doi:10.1126/science.133.3467.1795. PMID 13744853.

- ^ a b Klinefelter, HF (1986). "Klinefelter syndrome: historical background and development". South Med J. 79 (9): 1089–1093. doi:10.1097/00007611-198609000-00012. PMID 3529433.

- ^ Denschlag, Dominik, MD; Clemens, Tempfer, MD; Kunze, Myriam, MD; Wolff, Gerhard, MD; Keck, Christoph, MD (October 2004). "Assisted reproductive techniques in patients with Klinefelter syndrome: A critical review". Fertility and Sterility. 82 (4): 775–779. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.09.085. PMID 15482743.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Leask, Kathryn (October 2005). "Klinefelter syndrome". National Library for Health, Specialist Libraries, Clinical Genetics. National Library for Health. Retrieved 2007-04-07.

- ^ Hultborn, R; Hanson, C; Kopf, I; Verbiene, I; Warnhammar, E; Weimarck, A (1997 November–December). "Prevalence of Klinefelter syndrome in male breast cancer patients". Anticancer Res. 17 (6D): 4293–4297. PMID 9494523.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Graham, JM Jr; Bashir, AS; Stark, RE; Silbert, A; Walzer, S (June 1988). "Oral and written language abilities of XXY boys: implications for anticipatory guidance". Pediatrics. 81 (6): 795–806. PMID 3368277.

- ^ Boone KB; Swerdloff RS; Miller BL; et al. (May 2001). "Neuropsychological profiles of adults with Klinefelter syndrome". J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 7 (4): 446–56. doi:10.1017/S1355617701744013. PMID 11396547.

{{cite journal}}:|first10=missing|last10=(help);|first11=missing|last11=(help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 21217608, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 21217608instead. - ^ Chow, J; Yen, Z; Ziesche, S; Brown, C (2005). "Silencing of the mammalian X chromosome". Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 6: 69–92. doi:10.1146/annurev.genom.6.080604.162350. PMID 16124854.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|author-name-separator=(help); Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Blaschke, RJ; Rappold, G (2006). "The pseudoautosomal regions, SHOX and disease. Curr Opin Genet Dev". Jun;. 16 (3): 233–9. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2006.04.004. PMID 16650979.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|author-name-separator=(help); Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Jacobs PA, Strong JA (January 31, 1959). "A case of human intersexuality having a possible XXY sex-determining mechanism". Nature. 183 (4657): 302–3. doi:10.1038/183302a0. PMID 13632697.

- ^ Jacobs PA (September 1982). "The William Allan Memorial Award address: human population cytogenetics: the first twenty-five years". Am J Hum Genet. 34 (5): 689–98. PMC 1685430. PMID 6751075.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 7567329 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=7567329instead. - ^ Velissariou, V; Christopoulou, S; Karadimas, C; Pihos, I; Kanaka-Gantenbein, C; Kapranos, N; Kallipolitis, G; Hatzaki, A. (2006). "Rare XXY/XX mosaicism in a phenotypic male with Klinefelter syndrome: case report". Eur J Med Genet. 49 (4): 331–337. doi:10.1016/j.ejmg.2005.09.001. PMID 16829354.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|author-name-separator=(help); Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 1163864 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 1163864instead. - ^ Bojesen A, Gravholt CH (April 2007). "Klinefelter syndrome in clinical practice". Nat Clin Pract Urol. 4 (4): 192–204. doi:10.1038/ncpuro0775. PMID 17415352.

- ^ Abramsky L, Chapple J (April 1997). "47,XXY (Klinefelter syndrome) and 47,XYY: estimated rates of and indication for postnatal diagnosis with implications for prenatal counselling". Prenat Diagn. 17 (4): 363–8. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0223(199704)17:4<363::AID-PD79>3.0.CO;2-O. PMID 9160389.

- ^ a b Klinefelter HF Jr, Reifenstein EC Jr, Albright F. (1942). "Syndrome characterized by gynecomastia, aspermatogenesis without a-Leydigism and increased excretion of follicle-stimulating hormone". J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2 (11): 615–624. doi:10.1210/jcem-2-11-615.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Bojesen A, Juul S, Gravholt CH (Feb 2003). "Prenatal and postnatal prevalence of Klinefelter syndrome: a national registry study". Clin Endocrinol Metab. 88 (2): 622–6. doi:10.1210/jc.2002-021491. PMID 12574191.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Kamischke A, Baumgardt A, Horst J, Nieschlag E (Jan–Feb 2003). "Clinical and diagnostic features of patients with suspected Klinefelter syndrome". J Androl. 24 (1): 41–8. PMID 12514081.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Smyth CM, Bremner WJ (22 June 1998). "Klinefelter syndrome". Arch Intern Med. 158 (12): 1309–14. doi:10.1001/archinte.158.12.1309. PMID 9645824.

- ^ Grzywa-Celińska A, Rymarz E, Mosiewicz J (October 2009). "[Diagnosis differential of Klinefelter's syndrome in a 24-year old male hospitalized with sudden dyspnoea--case report]". Pol. Merkur. Lekarski (in Polacco). 27 (160): 331–3. PMID 19928664.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Kurková S, Zemanová Z, Hána V, Mayerová K, Pacovská K, Musilová J, Stĕpán J, Michalová K (April 1999). "[Molecular cytogenetic diagnosis of Klinefelter's syndrome in men more frequently detects sex chromosome mosaicism than classical cytogenetic methods]". Cas. Lek. Cesk. (in Czech). 138 (8): 235–8. PMID 10510542.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 8085664, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 8085664instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 10521836 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=10521836instead. - ^ Sanz-Cortés M, Raga F, Cuesta A, Claramunt R, Bonilla-Musoles F (November 2006). "Prenatally detected double trisomy: Klinefelter and Down syndrome". Prenat. Diagn. 26 (11): 1078–80. doi:10.1002/pd.1561. PMID 16958145.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Simm PJ, Zacharin MR (April 2006). "The psychosocial impact of Klinefelter syndrome--a 10 year review". J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 19 (4): 499–505. PMID 16759035.

- ^ Fullerton G, Hamilton M, Maheshwari A. (2010). "Should non-mosaic Klinefelter syndrome men be labelled as infertile in 2009?". Hum Reprod. 25 (3): 588–97. doi:10.1093/humrep/dep431. PMID 20085911.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Herlihy AS, McLachlan RI, Gillam L, Cock ML, Collins V, Hallpmiday JL (July 2011). "The psychosocial impact of Klinefelter syndrome and factors influencing quality of life". Genet. Med. 13 (7): 632–42. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182136d19. PMID 21546843.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Swerdlow AJ, Higgins CD, Schoemaker MJ, Wright AF, Jacobs PA (December 2005). "Mortality in patients with Klinefelter syndrome in Britain: a cohort study". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 90 (12): 6516–22. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-1077. PMID 16204366.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Price WH, Clayton JF, Wilson J, Collyer S, De Mey R (December 1985). "Causes of death in X chromatin positive males (Klinefelter's syndrome)". J Eppmidemiol Community Health. 39 (4): 330–6. doi:10.1136/jech.39.4.330. PMC 1052467. PMID 4086964.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bojesen A, Juul S, Birkebaek N, Gravholt CH (August 2004). "Increased mortality in Klinefelter syndrome". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 89 (8): 3830–4. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-0777. PMID 15292313.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jacobs, PA. (1979). "Recurrence risks for chromosome abnormalities". Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 15 (5C): 71–80. PMID 526617.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ MACLEAN, N.; Harnden, DG.; Court Brown, WM. (Aug 1961). "Abnormalities of sex chromosome constitution in newborn babies". Lancet. 2 (7199): 406–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(61)92486-2. PMID 13764957.

- ^ Visootsak, J.; Aylstock, M.; Graham, JM. (Dec 2001). "Klinefelter syndrome and its variants: an update and review for the primary pediatrician". Clin Pediatr (Phila). 40 (12): 639–51. doi:10.1177/000992280104001201. PMID 11771918.

- ^ Matlach, J.; Grehn, F.; Klink, T. (Jan 2012). "Klinefelter Syndrome Associated With Goniodysgenesis". J Glaucoma. 22 (5): e7–8. doi:10.1097/IJG.0b013e31824477ef. PMID 22274665.

- ^ Morris, JK.; Alberman, E.; Scott, C.; Jacobs, P. (Feb 2008). "Is the prevalence of Klinefelter syndrome increasing?". Eur J Hum Genet. 16 (2): 163–70. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201956. PMID 18000523.

Further reading

- Virginia Isaacs Cover (2012). Living with Klinefelter Syndrome, Trisomy X and 47,XYY: A Guide for Families and Individuals Affected by Extra X and Y Chromosomes. ISBN 978-0-615-57400-4.