Endometrial cancer

| Endometrial cancer | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Oncology |

Endometrial cancer is a cancer which arises from the lining of the uterus, which is known as the endometrium. It most typically occurs in the decades after menopause, when the first sign is often vaginal bleeding.

It is associated with obesity and with excessive estrogen exposure. Approximately 40% of cases can be attributed to obesity.[1] It often develops from endometrial hyperplasia (overgrowth of normal endometrium). Endometrial cancer is sometimes loosely referred to as "uterine cancer", although cancer can also arise from other tissues of the uterus, as occurs in cervical cancer, sarcoma of the myometrium, and trophoblastic disease.[2] The most frequent cellular type is endometrioid carcinoma, which accounts for more than 80% of all cases.[1]

The leading treatment option is usually total abdominal hysterectomy (surgical removal of the uterus) with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (removal of the fallopian tubes and ovaries on both sides). The five year survival rate in the United States is over 80%.[3] When the disease is caught in the early stages, the prognosis is favorable.

Globally as of 2012, endometrial cancers occurred in 320,000 women and caused 76,000 deaths.[4] They are the most common cancers of the female reproductive tract in developed countries. Incidence of endometrial cancer is slowly rising due to the increasing number of elderly people and increasing rates of obesity. Endometrial carcinoma is the third most common cause of death from female cancers, behind ovarian and cervical cancer.

Signs and symptoms

Vaginal bleeding or spotting in women after menopause occurs in 90% of endometrial cancer.[5][6] Bleeding is especially common with adenocarcinoma, occurring in 2/3rd of cases.[5][7] Abnormal menstrual periods or extremely long, heavy, or frequent episodes of bleeding in women before menopause may also be a sign of endometrial cancer.

Symptoms, other than bleeding, do not occur commonly. These symptoms include thin white or clear vaginal discharge in postmenopausal women.[7] More advanced disease shows more obvious symptoms or signs that can be detected on a physical examination. The uterus may become enlarged or the cancer may spread, causing lower abdominal pain or pelvic cramping.[7] The uterus may also fill with pus.[8] Of those with these symptoms 10-15% have cancer.[9]

Risk factors

Risk factors for endometrial cancer include obesity, diabetes mellitus, breast cancer, use of tamoxifen, never having had a child, late menopause, and high levels of estrogen.[9] Increasing age is another risk factor.[8] Immigration studies show that there is some environmental component to endometrial cancer.[7] These environmental risk factors are not well characterized.[10]

Hormones

Most of the risk factors for endometrial cancer involve high levels of estrogens. In obesity, the excess of adipose tissue increases conversion of androstenedione into estrone, an estrogen. Higher levels of estrone in the blood causes less or no ovulation and exposes the endometrium to continuously high levels of estrogens.[7][11] Obesity also causes less estrogen to be removed from the blood.[11] Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), which also causes irregular or no ovulation, is associated with higher rates of endometrial cancer for the same reasons as obesity.[7] Specifically, obesity, type II diabetes, and insulin resistance are risk factors for type I endometrial cancer.[12] Obesity increases the risk for endometrial cancer by 3-4 times.[13]

Estrogen replacement therapy during menopause when not balanced with progestin is another risk factor. Higher doses or longer periods of estrogen therapy have higher risks of endometrial cancer.[11] Women of lower weight are at greater risk from unopposed estrogen.[1] A longer period of fertility—either from an early first menstrual period or late menopause—is also a risk factor.[14] Unopposed estrogen raises an individual's risk of endometrial cancer by 2-10 fold, depending on weight and length of therapy.[1]

Genetics

Genetic disorders can also cause endometrial cancer. Lynch syndrome, an autosomal dominant genetic disorder that causes colorectal cancer, also causes endometrial cancer, especially before menopause. Women with Lynch syndrome have a 40–60% risk of developing endometrial cancer, higher than their risk of developing colorectal cancer or ovarian cancer.[7] Ovarian cancer and endometrial cancer develop simultaneously in 20% of people.[10] Carcinogenesis in Lynch syndrome comes from a mutation in MLH1 and/or MLH2: genes that participate in the process of mismatch repair, which allows a cell to correct mistakes in the DNA.[7] Other genes mutated in Lynch syndrome include MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2, also mismatch repair genes. Women with Lynch syndrome represent 2-3% of endometrial cancer cases; some sources place this as high as 5%.[10][13] Endometrial cancer nearly always develops before colon cancer, on average, 11 years before.[10]

Women with a family history of endometrial cancer are at higher risk.[2] Two genes most commonly associated with gynecological cancers, BRCA1 and BRCA2, do not cause endometrial cancer. There is a loose association because breast and ovarian cancers are often treated with tamoxifen.[7] Cowden syndrome can also cause endometrial cancer. Women with this disorder have a 5-10% lifetime risk of developing endometrial cancer.[1]

Other health problems

Some therapies for other forms of cancer increase the risk of endometrial cancer. Tamoxifen, a drug used to treat estrogen-positive breast cancers, has been associated with endometrial cancer in approximately 0.1% of users, particularly older women, but the benefits for survival from tamoxifen generally outweigh the risk of endometrial cancer.[15] A 1-2 year course of tamoxifen approximately doubles the risk of endometrial cancer, and a 5-year course of therapy quadruples that risk.[14] Previously having ovarian cancer is a risk factor for endometrial cancer,[16] as is having previous radiotherapy. Specifically, ovarian granulosa cell tumors and thecomas are ovarian tumors associated with endometrial cancer. Low immune function has also been implicated in endometrial cancer.[8] High blood pressure is also a risk factor.[13] Alcohol consumption is associated with endometrial cancer, though the association has not been fully investigated and is not currently significant.[1]

Protective factors

Smoking and progestin are both protective against endometrial cancer. Smoking provides protection by altering the metabolism of estrogen and promoting weight loss and early menopause. This protective effect lasts long after smoking is stopped. Progestin is present in the combined oral contraceptive pill and the hormonal intrauterine device (IUD). Progestin reduces risk of endometrial cancer by 30-50% over 10–20 years. Obese women may need higher doses of progestin to be protected.[7] Having had more than 5 infants (grand multiparity) is also a protective factor.[8]

Pathophysiology

Endometrial cancer forms when normal cell growth in the endometrium encounters errors. Usually, when cells grow old or get damaged, they die, and new cells take their place. Cancer starts when new cells form unneeded, and old or damaged cells don’t die as they should. The buildup of extra cells often forms a mass of tissue called a growth or tumor. These abnormal cancer cells have many genetic abnormalities that cause them to grow excessively.[2]

10-20% of endometrial cancers, mostly Grade 3, the highest histologic grade, have mutations in a tumor suppressor gene, commonly p53 or PTEN. In 20% of endometrial hyperplasias and 50% of endometrioid cancers, PTEN suffers a loss-of-function mutation or a null mutation, making it less effective or completely ineffective.[17] Loss of PTEN function leads to up-regulation of the PI3k/Akt/mTOR pathway, which causes cell growth.[13] The p53 pathway can either be suppressed or highly activated in endometrial cancer. When a mutant version of p53 is overexpressed, the cancer tends to be particularly aggressive.[17] P53 mutations and chromosome instability are associated with serous carcinomas, which tend to resemble ovarian and Fallopian carcinomas. Serous carcinomas are thought to develop from endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma.[13]

PTEN and p27 loss of function mutations are associated with a good prognosis, particularly in obese women. 20% of endometrioid and serous carcinomas show expression of the Her2/neu oncogene, which carries a poor prognosis. CTNNB1 (beta-catenin; a transcription gene) mutations are found in 14-44% of endometrial cancers and may indicate a good prognosis, but the data is unclear.[17] Beta-catenin mutations are commonly found in endometrial cancers with squamous cells.[13] FGFR2 mutations are found in approximately 10% of endometrial cancers, and their prognostic significance is unclear.[17] SPOP is another tumor suppressor gene found to be mutated in some cases of endometrial cancer: 9% of clear cell endometrial carcinomas and 8% of serous endometrial carcinomas have mutations.[18]

Type I and type II cancers tend to have different mutations involved. ARID1A (mutations found in 40% of type I cancers), CTNNB1 (14-44%), FGFR2 (16%), KRAS (10-20%), PIK3R1 (43%), TP53 (10-20%), and PTEN (37-61%) are the genes most commonly mutated (point mutations) in type I cancers.[19][1] ARID1A is also mutated in 26% of clear cell carcinomas of the endometrium, and 18% of serous carcinomas. Epigenetic silencing of several genes is also commonly found in type I endometrial cancer. These genes include: MLH1 (silenced in 30% of type I cancers), RASSF1A (48%), SPRY2 (20%), and CDKN2A (10%).[1] TP53 and PPP2R1A are more commonly mutated in type II cancers.[19] TP53 is mutated in 90% and PPP2R1A is mutated in 17-41% of type II endometrial cancers. Mutations in other tumor suppressor genes are commonly mutated in Type II endometrial cancer. These include CDH1 (80-90% of cancers have loss of heterozygosity) and CDKN2A (40% have either loss of heterozygosity or are silenced).[1] PIK3CA is commonly mutated in both type I and type II cancers;[19] point mutations in this gene are found in 24-39% of Type I and 20-30% of Type II cancers.[1] In women with Lynch syndrome-associated endometrial cancer, microsatellite instability is common.[13] Two oncogenes are commonly mutated in type II endometrial cancer: PIK3CA (which can also be amplified), which is mutated in 20-30% of type II cancers; and PIK3R1, mutated in 12% of type II cancers. Several more oncogenes are commonly amplified in type II endometrial cancers: STK15 (amplified in 60% of type II endometrial cancers), CCNE1 (55%), ERBB2 (30%), and CCND1 (26%).[1]

Development of an endometrial hyperplasia (overgrowth of endometrial cells) is a significant risk factor because hyperplasias can and often do develop into adenocarcinoma, though cancer can develop without the presence of a hyperplasia.[11] 8-30% of atypical endometrial hyperplasias develop into cancer within 10 years, whereas 1-3% of non-atypical hyperplasias do so in the same timeframe.[20] An atypical hyperplasia is one with visible abnormalities in the nuclei. Premalignant endometrial hyperplasias are also referred to as endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia.[7] Mutations in the KRAS gene can cause endometrial hyperplasia and therefore type I endometrial cancer.[17] Endometrial glandular dysplasia occurs with an overexpression of p53, and develops into a serous carcinoma.[8]

Diagnosis

Examination

Routine screening of asymptomatic women is not indicated, since the disease is highly curable in its early stages. Instead, women, particularly menopausal women, should be aware of the symptoms and risk factors of endometrial cancer. A Pap smear is not a useful diagnostic tool for endometrial cancer because the smear will be normal 50% of the time. Results from a pelvic examination are frequently normal, especially in the early stages of disease. Changes in the size, shape or consistency of the uterus and/or its surrounding, supporting structures may exist when the disease is more advanced.[7] Cervical stenosis, the narrowing of the cervical opening, is a sign of endometrial cancer when pus or blood is found collected in the uterus (pyometra or hematometra).[6]

Women with Lynch syndrome should begin to have annual biopsy screening at the age of 35. Some women with Lynch syndrome elect to have a prophylactic hysterectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy to negate the risk of endometrial and ovarian cancer.[7]

Transvaginal ultrasound to examine the endometrial thickness in women with postmenopausal bleeding is increasingly being used to aid in the diagnosis of endometrial cancer in the United States.[7] In the United Kingdom, both an endometrial biopsy and a transvaginal ultrasound are the standard of care for diagnosing endometrial cancer.[8] The homogeneity of the tissue visible on transvaginal ultrasound can help to indicate whether the thickness is malignant. Ultrasound findings alone are not conclusive in cases of endometrial cancer, so another screening method (e.g. endometrial biopsy) must be used in conjunction. Other imaging studies are of limited use. CT scans are used for preoperative imaging of tumors that appear advanced on physical exam or have a high-risk subtype.[7] They can also be used to investigate extrapelvic disease.[8] An MRI can be of some use in determining if the cancer has spread to the cervix or if it is an endocervical adenocarcinoma.[7] MRI is also useful for examining the nearby lymph nodes.[8]

Dilation and curettage (D&C) or an endometrial biopsy are used to obtain a tissue sample for histological examination. Endometrial biopsy is the less invasive option, but it may not give conclusive results every time. Hysteroscopy only shows the gross anatomy of the endometrium, which is often not indicative of cancer, and is therefore not used, unless in conjunction with a biopsy.[7] However, hysteroscopy can be used to confirm a diagnosis of cancer. New evidence shows that D&C has a higher false negative rate than endometrial biopsy.[13]

Before treatment is begun, several other studies are recommended. These include a chest x-ray, liver function tests, and kidney function tests.[13]

Classification

Endometrial cancer includes carcinomas, which are divided into Type I and Type II cancers and includes endometrioid adenocarcinoma, uterine papillary serous carcinoma, uterine clear-cell carcinoma, and several other very rare forms.

Carcinoma

The vast majority of endometrial cancers are carcinomas (usually adenocarcinomas), meaning that they originate from the single layer of epithelial cells that line the endometrium and form the endometrial glands. There are many microscopic subtypes of endometrial carcinoma, but they are broadly organized into two categories, type I and type II, based on clinical features and pathogenesis. The two subtypes are genetically distinct.[7]

Type I endometrial carcinomas occur most commonly before and around the time of menopause. In the United States they are more common in white women, often with a history of endometrial hyperplasia. Type I endometrial cancers are often low-grade, minimally invasive into the underlying uterine wall (myometrium), estrogen-dependent, and have a good outcome.[7] Type I carcinomas represent 75%-90% of endometrial cancer.[7][8]

Type II endometrial carcinomas usually occur in older, post-menopausal women, in the United States are more common in Black women, and are not associated with increased exposure to estrogen or a history of endometrial hyperplasia. Type II endometrial cancers are often high-grade, with deep invasion into the underlying uterine wall (myometrium), and are of the serous or clear cell type, and carry a poorer prognosis. They can appear to be epithelial ovarian cancer on evaluation of symptoms.[7] They tend to present later than Type I tumors and are more aggressive, with a greater risk of relapse or metastasis.[8] Type II cancers are estrogen-independent.[13]

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma

In endometrioid adenocarcinoma, the cancer cells grow in patterns reminiscent of normal endometrium, with many new glands formed from columnar epithelium with some abnormal nuclei. Low-grade endometrioid adenocarcinomas have well differentiated cells, have not invaded the myometrium, and are seen alongside endometrial hyperplasia. The tumor's glands form very close together, without the stromal tissue that normally separates them. Higher-grade endometrioid adenocarcinomas have less well-differentiated cells, have more solid sheets of tumor cells no longer organized into glands, and are associated with an atrophied endometrium. There are several subtypes of endometrioid adenocarcinoma with similar prognoses, including villoglandular, secretory, and ciliated cell variants. There is also a subtype characterized by squamous differentiation. Some endometrioid adenocarcinomas have foci of mucinous carcinoma.[7]

The genetic mutations most commonly associated with endometrioid adenocarcinoma are in the genes PTEN, a tumor suppressor; PIK3CA, a kinase; KRAS, a GTPase that functions in signal transduction; and CTNNB1, involved in adhesion and cell signaling. The CTNNB1 (beta-catenin) mutation is most commonly mutated in the squamous subtype of endometrioid adenocarcinoma.[21]

Serous carcinoma

Serous carcinoma is a type II endometrial tumor that makes up 5-10% of diagnosed endometrial cancer and is common in postmenopausal women with atrophied endometrium and Black women. Serous endometrial carcinoma is aggressive and often invades the myometrium and metastasizes within the peritoneum (seen as omental caking) or the lymphatic system. Histologically, it appears with many atypical nuclei, papillary structures, and, in contrast to endometrioid adenocarcinomas, rounded cells instead of columnar cells. 30% of endometrial serous carcinomas also have psammoma bodies.[7][11] Serous carcinomas spread differently than most other endometrial cancers; they can spread outside the uterus without invading the myometrium.[11]

The genetic mutations seen in serous carcinoma are chromosomal instability and mutations in TP53, an important tumor suppressor gene.[21]

Clear cell carcinoma

Clear cell carcinoma is a type II endometrial tumor that makes up less than 5% of diagnosed endometrial cancer. Like serous cell carcinoma, it is usually aggressive and carries a poor prognosis. Histologically, it is characterized by the features common to all clear cells: the eponymous clear cytoplasm when H&E stained and visible, distinct cell membranes.[7] The p53 cell signaling system is not active in endometrial clear cell carcinoma.[8] This form of endometrial cancer is more common in postmenopausal women.[11]

Mucinous carcinoma

Mucinous carcinomas are a rare form of endometrial cancer, making up less than 1-2% of all diagnosed endometrial cancer. Mucinous endometrial carcinomas are most often stage I and grade I, giving them a good prognosis. They typically have well-differentiated columnar cells organized into glands with the characteristic mucin in the cytoplasm. Mucinous carcinomas must be differentiated from cervical adenocarcinoma.[7]

Mixed or undifferentiated carcinoma

Mixed carcinomas are those that have both type I and type II cells, with one making up at least 10% of the tumor.[7] These include the malignant mixed Müllerian tumor, which derives from endometrial epithelium and has a poor prognosis.[22] Mixed Müllerian tumors tend to occur in postmenopausal women.[11]

Undifferentiated endometrial carcinomas make up less than 1-2% of diagnosed endometrial cancers. They have a worse prognosis than grade III tumors. Histologically, these tumors show sheets of identical epithelial cells with no identifiable pattern.[7]

Other carcinomas

Non-metastatic squamous cell carcinoma and transitional cell carcinoma are very rare in the endometrium. Squamous cell carcinoma of the endometrium has a poor prognosis.[7]

Sarcoma

|

|

In contrast to endometrial carcinomas, the uncommon endometrial stromal sarcomas are cancers that originate in the non-glandular connective tissue of the endometrium. They are generally non-aggressive and, if they recur, can take decades. Metastases to the lungs and pelvic or peritoneal cavities are the most frequent.[11]

Metastasis

Endometrial cancer frequently metastasizes to the ovaries and Fallopian tubes[16] when the cancer is located in the upper part of the uterus, and the cervix when the cancer is in the lower part of the uterus. The cancer usually first spreads into the myometrium and the serosa, then into other reproductive and pelvic structures. When the lymphatic system is involved, the pelvic and para-aortal nodes are usually first to become involved, but in no specific pattern, unlike cervical cancer. More distant metastases are spread by the blood and often occur in the lung, as well as the liver, brain, and bone.[7]

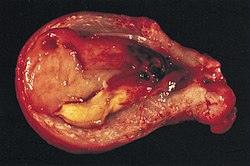

Histopathology

There is a three-tiered system for histologically classifying endometrial cancers, ranging from cancers with well-differentiated cells (grade I), to very poorly-differentiated cells (grade III).[14] Grade I cancers are the least aggressive and have the best prognosis, while grade III tumors are the most aggressive and likely to recur. Grade II cancers are intermediate between grades I and III in terms of cell differentiation and aggressiveness of disease.[7]

The histopathology of endometrial cancers is highly diverse. The most common finding is a well-differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma,[22] which is composed of numerous, small, crowded glands with varying degrees of nuclear atypia, mitotic activity, and stratification. This often appears on a background of endometrial hyperplasia. Frank adenocarcinoma may be distinguished from atypical hyperplasia by the finding of clear stromal invasion, or "back-to-back" glands which represent nondestructive replacement of the endometrial stroma by the cancer. With progression of the disease, the myometrium is infiltrated.[23]

Staging

Endometrial carcinoma is surgically staged using the FIGO cancer staging system. The 2010 FIGO staging system is as follows:[24]

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| IA | Tumor is confined to the uterus with less than half myometrial invasion |

| IB | Tumor is confined to the uterus with more than half myometrial invasion |

| II | Tumor involves the uterus and the cervical stroma |

| IIIA | Tumor invades serosa or adnexa |

| IIIB | Vaginal and/or parametrial involvement |

| IIIC1 | Pelvic lymph node involvement |

| IIIC2 | Para-aortic lymph node involvement, with or without pelvic node involvement |

| IVA | Tumor invades bladder mucosa and/or bowel mucosa |

| IVB | Distant metastases including abdominal metastases and/or inguinal lymph nodes |

Myometrial invasion and involvement of the pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes are the most commonly seen patterns of spread.[5]

-

Stage IA and IB endometrial cancer

-

Stage II endometrial cancer

-

Stage III endometrial cancer

-

Stage IV endometrial cancer

Management

Surgery

The primary treatment is surgical. Surgical treatment typically consists of hysterectomy including a salpingo-oophorectomy, which is the removal of the uterus, ovaries, and Fallopian tubes. Lymphadenectomy, or removal of pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes, is performed for tumors of histologic grade II or above.[9] Lymphadenectomy is routinely performed for all stages of endometrial cancer in the United States, but in the United Kingdom, the lymph nodes are typically only removed with disease of stage II or greater.[8] The topic of lymphadenectomy and what survival benefit it offers in stage I disease is still being debated.[13] In stage III and IV cancers, cytoreductive surgery is the norm,[9] and a biopsy of the omentum may also be included. Laparotomy, an open-abdomen procedure, is the traditional surgical protocol; however, laparoscopy (keyhole surgery) is associated with lower operative morbidity. The two procedures have no difference in overall survival.[25] 90% of women are treated with some form of surgery.[14] Removal of the uterus via the abdomen is recommended over removal of the uterus via the vagina because it gives the opportunity to examine and obtain washings of the abdominal cavity to detect any further evidence of cancer. Staging of the cancer is done during the surgery.[7] In type II cancers, a bilateral mastectomy is often included in treatment for prophylaxis.[6]

Surgery is usually the primary treatment of endometrial cancer. The few contraindications include inoperable tumor, massive obesity, a particularly high-risk operation, or a desire to preserve fertility.[7] These contraindications happen about 5-10% of the time.[13] Women who wish to preserve their fertility and have stage I cancer can be treated with progestins, with or without concurrent tamoxifen therapy. This therapy can be continued until the cancer does not respond to treatment or until childbearing is done.[7] Uterine perforation may occur during a dilation and curettage (D&C) or an endometrial biopsy.[26]

In stage IV disease, where there are distant metastases, surgery can be used as part of palliative therapy.[13]

Add-on therapy

Surgery can be combined with radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy in cases of high-risk or high-grade cancers. In cases where surgery is not indicated, palliative chemotherapy is an option; higher-dose chemotherapy is associated with longer survival. Adjuvant chemotherapy is a recent innovation, consisting of some combination of paclitaxel (or other taxanes like docetaxel), doxorubicin (and other anthracyclines), and platins (particularly cisplatin and carboplatin). Adjuvant chemotherapy has been found to increase survival in stage III and IV cancer more than Add-on chemotherapy.[9][14][27][13] Mutations in mismatch repair genes can lead to resistance against platins.[28]

Adjuvant radiotherapy is commonly used in early-stage endometrial cancer. It can be delivered through vaginal brachytherapy (VBT), which is becoming the preferred route due to its reduced toxicity, or external beam radiotherapy (EBRT). VBT is used to treat any remaining cancer solely in the vagina, whereas EBRT can be used to treat remaining cancer elsewhere in the pelvis following surgery. However, the benefits of adjuvant radiotherapy are controversial. Though EBRT significantly reduces the rate of relapse in the pelvis, overall survival and metastasis rates are not improved.[5] VBT provides a better quality of life than EBRT.[13] Radiotherapy can also be used prior to surgery in certain cases. When pre-operative imaging or clinical evaluation shows tumor invading the cervix, radiation can be given before a total hysterectomy is performed.[6] Brachytherapy can also be used when there is a contraindication for hysterectomy.[13]

Hormonal therapy is not beneficial and not used in most cases,[9] though it was once thought to have some beneficial effect.[5] If a tumor is well-differentiated and known to have progesterone and estrogen receptors, progestins may be used in treatment.[27] 25% of metastatic endometrioid cancers show a response to progestins. Also, endometrial stromal sarcomas can be treated with hormonal agents, including tamoxifen, 17-hydroxyprogesterone caproate, letrozole, megestrol acetate, and medroxyprogesterone.[11] Palliative chemotherapy is often used to treat recurrent endometrial cancer, particularly capecitabine and gemcitabine.[27]

Side effects of chemotherapy are common. These include hair loss, low neutrophil levels in the blood, and gastrointestinal problems.[9] Add-on radiotherapy for endometrial cancer can be delivered either through external beam radiotherapy or vaginal brachytherapy. Both are associated with side effects, particularly in the GI tract.[5]

Monitoring

The tumor marker CA-125 is frequently found to be elevated in endometrial cancer and can be used to monitor response to treatment, particularly in serous cell cancer or advanced disease.[7][16] Periodic MRIs or CT scans may be recommended in advanced disease and all with a history of endometrial cancer should receive more frequent pelvic examinations for the 5 years following treatment.[7] Examinations conducted every 3-4 months are recommended for the first two years following treatment, and every 6 months for the next 3 years.[13]

Women with endometrial cancer should not have routine surveillance imaging to monitor the cancer unless new symptoms appear or tumor markers begin rising. Imaging without these indications is discouraged because it is unlikely to detect a recurrence or improve survival, and because it has its own costs and side effects.[29] If a recurrence is suspected, PET/CT scanning is recommended.[13]

Prognosis

In the United States, where approximately 8,000 people die annually from endometrial cancer, white women have a higher survival rate than African-American women, who tend to develop more aggressive forms of the disease.[11] Among survivors satisfaction with information provided about the disease and treatment increases the quality of life, lowers depression and results in less anxiety.[30]

Survival rates

| Stage | 5 year survival rate |

|---|---|

| I-A | 88% |

| I-B | 75% |

| II | 69% |

| III-A | 58% |

| III-B | 50% |

| III-C | 47% |

| IV-A | 17% |

| IV-B | 15% |

In the Netherlands a 2013 study found the 5-year survival rate for endometrial adenocarcinoma following appropriate treatment was 80%.[32] Most women, over 70%, have FIGO stage I cancer, which has the best prognosis. Stage III and IV cancer has a worse prognosis, but is relatively rare, occurring in only 13% of cases. Older age indicates a worse prognosis.[9] The median survival time for stage III-IV endometrial cancer is 9–10 months.[33]

Recurrence rates

Recurrence of early stage endometrial cancer ranges from 3 to 17%, depending on primary and adjuvant treatment. Most recurrences (70%) occur in the first three years.[32]

Higher-staged cancers are more likely to recur — those that have invaded the myometrium or cervix, or that have metastasized into the lymphatic system, are particularly likely to recur. Papillary serous carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, and endometrioid carcinoma are the subtypes at the highest risk of recurrence.[14] High-grade histological subtypes are also at elevated risk for recurrence.[8]

The most common site of recurrence is in the vagina;[5] vaginal relapses of endometrial cancer have the best prognosis. If relapse occurs from a cancer that has not been treated with radiation, EBRT is the first-line treatment and is often successful. If a cancer treated with radiation occurs, pelvic exenteration is the only option for curative treatment. Palliative chemotherapy, cytoreductive surgery, and radiation are also performed.[7] Radiation therapy (VBT and EBRT) for a local vaginal recurrence has a 50% 5 year survival rate. Pelvic recurrences are treated with surgery and radiation, and abdominal recurrences are treated with radiation and, if possible, chemotherapy.[13]

Epidemiology

Endometrial cancer is the most frequently diagnosed gynecologic cancer and in women the fourth most prevalent cancer overall in the United States.[7][11] It has an incidence of 12.9 cases per 100,000 women annually in developed countries.[14] Worldwide, approximately 320,000 women are diagnosed with endometrial cancer each year and 76,000 die, making it the sixth most prevalent cancer in women.[1] It is more common in developed countries; the risk of endometrial cancer is 1.6% compared to 0.6% in developing countries.[9] Northern Europe, Eastern Europe, and North America have the highest rates of endometrial cancer, comprising 48% of diagnoses in 2012, whereas Africa and West Asia have the lowest rates. Asia saw 41% of the world's endometrial cancer diagnoses in 2012.[1] Unlike most cancers, the incidence rate has risen dramatically in recent years, including an increase of over 40% in the United Kingdom between 1993 and 2013.[9] Some of this rise may be due to the increase in obesity rates in developed countries,[14] increasing life expectancies, and lower birth rates.[7] The average woman's lifetime risk for endometrial cancer is approximately 2-3%.[10] An estimated 40% of cases are thought to be related to obesity.[1] In 2008, 288,000 cases were diagnosed worldwide, making it the sixth most prevalent cancer in women that year. In the UK, approximately 7400 cases are diagnosed annually, and in the EU, approximately 88,000.[13]

It appears most frequently during perimenopause and menopause, between the ages of 50 and 65;[11] overall, 75% of endometrial cancer occurs after menopause.[5] However, 5% of cases occur in women younger than 40 and 10-15% occur in women under 50 years of age. This age group is at risk for developing ovarian cancer at the same time.[11] Less than 5% of cases are associated with Lynch syndrome.[7] The median age of diagnosis is 63 years of age.[13]

Endometrial adenocarcinoma is the most common endometrial cancer, accounting for over 90% of cases. It was diagnosed in approximately 280,000 women in the world in 2008, and killed 33,000 in developed countries that year.[14]

Research

There are several experimental therapies for endometrial cancer under research. Trastuzumab (Herceptin) has been used in cancers known to be positive for the Her2/neu oncogene, but research is still underway. Immunologic therapies are also under investigation, particularly in uterine papillary serous carcinoma.[17] Research is ongoing on the use of metformin, a diabetes medication, inobese women with endometrial cancer before surgery. Early research has shown it to be effective in slowing the rate of cancer cell proliferation.[19][12] Preliminary research has shown that preoperative metformin administration can reduce expression of tumor markers. However, long-term use of metformin has not been shown to have a preventative effect against developing cancer in the first place, but may improve overall survival.[12] Temsirolimus, an mTOR inhibitor, is under investigation as a potential treatment. Ridaforolimus is also being researched as a treatment for people who have previously had chemotherapy. Preliminary research has been promising, and a stage II trial for ridaforolimus was completed.[13]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n International Agency for Research on Cancer (2014). World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. Chapter 6.7. ISBN 978-92-832-0429-9.

- ^ a b c "What You Need To Know: Endometrial Cancer". NCI. National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ^ "SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Endometrial Cancer". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ^ International Agency for Research on Cancer (2014). World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. Chapter 5.12. ISBN 978-92-832-0429-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Template:Cite cochrane

- ^ a b c d Reynolds, RK; Loar III, PV (2010). "Gynecology". In Doherty, GM (ed.). Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Surgery (13th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-163515-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am Hoffman, BL; Schorge, JO; Schaffer, JI; Halvorson, LM; Bradshaw, KD; Cunningham, FG, eds. (2012). "Endometrial Cancer". Williams Gynecology (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-171672-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Saso, S; Chatterjee, J; Georgiou, E; Ditri, AM; Smith, JR; Ghaem-Maghami, S (2011). "Endometrial cancer". BMJ. 343: d3954–d3954. doi:10.1136/bmj.d3954. PMID 21734165.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Template:Cite cochrane

- ^ a b c d e Ma, J; Ledbetter, N; Glenn, L (2013). "Testing women with endometrial cancer for lynch syndrome: should we test all?". Journal of the Advanced Practitioner in Oncology. 4 (5): 322–30. PMC 4093445. PMID 25032011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Soliman, PT; Lu, KH (2013). "Neoplastic Diseases of the Uterus". In Lentz, GM; Lobo, RA; Gershenson, DM; Katz, VL (eds.). Comprehensive Gynecology (6th ed.). Mosby. ISBN 978-0-323-06986-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|displayeditors=ignored (|display-editors=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Sivalingam, VN; Myers, J; Nicholas, S; Balen, AH; Crosbie, EJ (2014). "Metformin in reproductive health, pregnancy and gynaecological cancer: established and emerging indications". Human Reproduction Update. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu037. PMID 25013215.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Colombo N, Preti E, Landoni F; et al. (2013). "Endometrial cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up". Ann. Oncol. 24 Suppl 6: vi33–8. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdt353. PMID 24078661.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Template:Cite cochrane

- ^ Template:Cite cochrane

- ^ a b c Coleman, RL; Ramirez, PT; Gershenson, DM (2013). "Neoplastic Diseases of the Ovary". In Lentz, GM; Lobo, RA; Gershenson, DM; Katz, VL (eds.). Comprehensive Gynecology (6th ed.). Mosby. ISBN 978-0-323-06986-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|displayeditors=ignored (|display-editors=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f Thaker, PH; Sood, AK. "Molecular Oncology in Gynecologic Cancer". In Lentz, GM; Lobo, RA; Gershenson, DM; Katz, VL (eds.). Comprehensive Gynecology (6th ed.). Mosby. ISBN 978-0-323-06986-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|displayeditors=ignored (|display-editors=suggested) (help) - ^ Mani, RS (2014). "The emerging role of speckle-type POZ protein (SPOP) in cancer development". Drug Discovery Today. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2014.07.009. PMID 25058385.

- ^ a b c d Suh, DH; Kim, JW; Kang, S; Kim, HJ; Lee, KH (2014). "Major clinical research advances in gynecologic cancer in 2013". Journal of Gynecologic Oncology. 25 (3): 236–248. doi:10.3802/jgo.2014.25.3.236. PMC 4102743. PMID 25045437.

- ^ Template:Cite cochrane

- ^ a b Colombo, N; Preti, E; Landoni, F; Carinelli, S; Colombo, A; Marini, C; Sessa, C (2011). "Endometrial cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up". Annals of Oncology. 22 (Supplement 6): vi35–vi39. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdr374. PMID 21908501.

- ^ a b Template:Cite cochrane

- ^ Weidner, N; Coté, R; Suster, S; Weiss, L, eds. (2002). Modern Surgical Pathology (2 Volume Set). WB Saunders. ISBN 978-0-7216-7253-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|displayeditors=ignored (|display-editors=suggested) (help) - ^ "Stage Information for Endometrial Cancer". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ Template:Cite cochrane

- ^ McGee, J; Covens, A (2013). "Gestational Trophoblastic Disease". In Lentz, GM; Lobo, RA; Gershenson, DM; Katz, VL (eds.). Comprehensive Gynecology (6th ed.). Mosby. ISBN 978-0-323-06986-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|displayeditors=ignored (|display-editors=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Smith, JA; Jhingran, A (2013). "Principles of Radiation Therapy and Chemotherapy in Gynecologic Cancer". In Lentz, GM; Lobo, RA; Gershenson, DM; Katz, VL (eds.). Comprehensive Gynecology (6th ed.). Mosby. ISBN 978-0-323-06986-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|displayeditors=ignored (|display-editors=suggested) (help) - ^ Guillotin, D; Martin, SA (2014). "Exploiting DNA mismatch repair deficiency as a therapeutic strategy". Experimental Cell Research. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.07.004. PMID 25017099.

- ^ "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question". Choosing Wisely. Society of Gynecologic Oncology. 31 October 2013. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- ^ Husson, O; Mols, F; van de Poll-Franse, LV (2011). "The relation between information provision and health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression among cancer survivors: a systematic review". Annals of Oncology. 22 (4): 761–772. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdq413. PMC 3065875. PMID 20870912.

- ^ "Survival by stage of endometrial cancer". American Cancer Society. 2 March 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- ^ a b Nicolaije, KA; Ezendam, NP; Vos, MC; Boll, D; Pijnenborg, JM; Kruitwagen, RF; Lybeert, ML; van de Poll-Franse, LV (2013). "Follow-up practice in endometrial cancer and the association with patient and hospital characteristics: A study from the population-based PROFILES registry". Gynecologic Oncology. 129 (2): 324–331. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.02.018. PMID 23435365.

- ^ Template:Cite cochrane