Mantis

Error: no context parameter provided. Use {{other uses}} for "other uses" hatnotes. (help).

| Mantodea Temporal range: Cretaceous–Recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult female Sphodromantis viridis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Infraclass: | |

| Superorder: | |

| Order: | Mantodea Burmeister, 1838

|

| Families | |

|

Acanthopidae | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Mantodea is an order of insects that contains over 2,400 species and about 430 genera of mantises (or praying mantises) in 15 families. They are distributed worldwide in temperate and tropical habitats. Most of the species are in the family Mantidae. Their lifespan is normally up to a year. Females sometimes practice sexual cannibalism, eating their mate after, or occasionally decapitating the male just before mating.

The closest relatives of mantises are the termites and cockroaches (Blattodea). They are sometimes confused with stick insects (Phasmatodea) and other elongated insects such as grasshoppers (Orthoptera), or other insects with raptorial forelegs such as mantisflies (Mantispidae).

Mantises were considered to have supernatural powers in early civilizations including Ancient Greece, Ancient Egypt and Assyria. A cultural trope imagines the female mantis as a femme fatale, devouring the male after mating. Mantises are among the insects most commonly kept as pets.

Etymology

The name mantodea is formed from the Ancient Greek words μάντις (mantis) meaning "prophet", and εἶδος (eidos) meaning "form" or "type". It was coined in 1838 by the German entomologist Hermann Burmeister.[1][2] The order is occasionally called the mantes, using a Latinized plural of Greek mantis. The name mantid properly refers only to members of the family Mantidae, which was, historically, the only family in the order, but with 14 additional families recognized in recent decades, this term is now potentially misleading. The other common name, praying mantis, applied to any species in the order,[3] but in Europe mainly to Mantis religiosa, comes from the typical "prayer-like" posture with folded fore-limbs.[4][5]

Taxonomy and evolution

There are over 2400 recognized species of mantis in about 430 genera.[6] The systematics of mantises have long been disputed. Mantises, along with stick insects (Phasmatodea), were once placed in the order Orthoptera with the cockroaches (now Blattodea) and rock crawlers (now Grylloblattodea). Kristensen (1991) combined Mantodea with the cockroaches and termites into the order Dictyoptera, suborder Mantodea.[7][8]

The classification most commonly adopted is that proposed by Beier in 1968. He divided the order into eight families.[9] Klass, in 1997, studied the external male genitalia and postulated that the families Chaeteessidae and Metallyticidae diverged from the other families at an early date.[10] However, the Mantidae and Thespidae are both polyphyletic, so the Mantoidea will have to be revised.[11]

The earliest mantis fossils are about 135 million years ago from Siberia.[11] Fossils of the group are rare: by 2007 there were only about 25 fossil species.[11] Fossil mantises, including one from Japan with spines on the front legs as in modern mantids, have been found in Cretaceous amber.[12] Most fossils in amber are nymphs; compression fossils (in rock) include adults. Fossil mantids from the Crato Formation in Brazil include the 10mm long Santanmantis axelrodi, described in 2003; as in modern mantids, the front legs were adapted for catching prey. Well-preserved specimens yield details as small as 5 μmetre through X-ray computed tomography.[11]

Biology

Anatomy

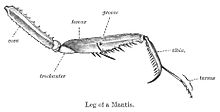

Mantises have two spiked, grasping forelegs ("raptorial legs") in which prey items are caught and held securely. In most insect legs, including the posterior four legs of a mantis, the coxa and trochanter combine as an inconspicuous base of the leg; in the raptorial legs however, the coxa and trochanter combine to form a segment about as long as the femur, which is a spiky part of the grasping apparatus (see illustration). Located at the base of the femur are a set of discoidal spines, usually four in number, but ranging from zero to as many as five depending on the species. These spines are preceded by a number of tooth-like tubercles, which, along with a similar series of tubercles along the tibia and the apical claw near its tip, give the foreleg of the mantis its grasp on its prey. The foreleg ends in a delicate tarsus made of between four and five segments and ending in a two-toed claw with no arolium and used as a walking appendage.[13]

The mantis thorax consists of a prothorax, a mesothorax, and a metathorax. In all species apart from the genus Mantoida, the prothorax, which bears the head and forelegs, is much longer than the other two thoracic segments. The prothorax is also flexibly articulated, allowing for a wide range of movement of the head and forelimbs while the remainder of the body remains more or less immobile. The articulation of the neck is also remarkably flexible; some species of mantis can rotate the head nearly 180 degrees.

Mantises have a visual range of up to 20 meters. Their compound eyes contain up to 10,000 ommatidia. The eyes are widely spaced and laterally situated, affording a wide binocular field of vision and, at close range, precise stereoscopic vision. The dark spot on each eye is a pseudopupil. As their hunting relies heavily on vision, mantises are primarily diurnal. Many species, however, fly at night, and then may be attracted to artificial lights. Nocturnal flight is especially important to males in search of less-mobile females that they locate by detecting their pheromones. Flying at night exposes mantises to fewer bird predators than diurnal flight would. Many mantises also have an auditory thoracic organ that helps them to avoid bats by detecting their echolocation and responding evasively.[13]

Mantises can be loosely categorized as being macropterous (long-winged), brachypterous (short-winged), micropterous (vestigial-winged), or apterous (wingless). If not wingless, a mantis has two sets of wings: the outer wings, or tegmina, are usually narrow, opaque, and leathery. They function as camouflage and as a shield for the hind wings. The hind wings are much broader, more delicate, and transparent. They are the main organs of flight, if any. Brachypterous species are at most minimally capable of flight, other species not at all. The wings are mostly erected in these mantises for alarming enemies and attracting females. Even in many macropterous species the female is much heavier than the male, has much shorter wings, and rarely takes flight if she is capable of it at all.

The abdomen of all mantises consist of ten tergites with a corresponding set of nine sternites visible in males and seven visible in females. The slim abdomen of most males allows them to take flight more easily while the thicker abdomen of the females houses the reproductive machinery for generating the ootheca. The abdomen of both sexes ends in a pair of cerci.

Diet and predation

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2014) |

Most mantises are exclusively predatory while exceptions occur. Insects are their primary prey, but the diet of a mantis changes as it grows larger. In its first instar a mantis eats small insects. In the final instar the diet still includes more insects than anything else, but large species sometimes prey on small scorpions, lizards, frogs, birds, snakes, fish, and even rodents.[citation needed]

The majority of mantises are ambush predators that only feed upon live prey a short distance within their reach. However, some ground and bark species actively pursue their prey. For example, members of a few genera such as the ground mantids, Entella, Ligaria and Ligariella, run over dry ground seeking prey much as tiger beetles do. Species that are predominantly ambush predators camouflage themselves and spend long periods standing perfectly still. They largely wait for their prey to stray within reach, but most mantises chase tempting prey if it strays closely enough. A mantis catches prey and grips them with grasping, spiked forelegs. The mantis usually holds its prey with one arm between the head and thorax, and the other on the abdomen. Then, if the prey does not resist, the mantis eats it alive. However, if the prey does resist, the mantis often eats it head first. Unlike sucking predatory arthropods such as assassin bugs, a mantis does not liquefy prey tissues or drain its prey's body fluids, but simply slices and chews it with its mandibles as convenient, often from one end.[citation needed]

The foregut of some species extends the whole length of the insect and can be used to store prey for digestion later. This may be advantageous in an insect that feeds intermittently.[14]

Chinese mantises have been found to gain benefits in survivorship, growth, and fecundity by supplementing their diet with pollen. In replicated laboratory tests the first instar actively fed on pollen just after hatching, thereby avoiding starvation in the absence of prey. The adults fed on pollen-laden insects, attaining fecundity as high as those fed on larger numbers of insects alone.[15]

Antipredator adaptations

Generally, mantises protect themselves by camouflage. When directly threatened, many mantis species stand tall and spread their forelegs, with their wings fanning out wide. The fanning of the wings makes the mantis seem larger and more threatening, with some species having bright colors and patterns on their hind wings and inner surfaces of their front legs for this purpose. If harassment persists, a mantis may strike with its forelegs and attempt to pinch or bite. As part of the bluffing (deimatic) threat display, some species also may produce a hissing sound by expelling air from the abdominal spiracles. When flying at night, at least some mantises are able to detect the echolocation sounds produced by bats, and when the frequency begins to increase rapidly, indicating an approaching bat, they stop flying horizontally and begin a descending spiral toward the safety of the ground, often preceded by an aerial loop or spin.[16][17]

Mantises, like stick insects, show rocking behavior in which the insect makes rhythmic, repetitive side-to-side movements. Functions proposed for this behaviour include the enhancement of crypsis by means of the resemblance to vegetation moving in the wind. However, the repetitive swaying movements may be most important in allowing the insects to discriminate objects from the background by their relative movement, a visual mechanism typical of animals with simpler sight systems. Rocking movements by these generally sedentary insects may replace flying or running as a source of relative motion of objects in the visual field.[18]

Mantises are camouflaged, most species being cryptically colored to resemble foliage or other backgrounds, both to avoid predators, and to better snare their prey.[19] The species from different families called flower mantises are aggressive mimics: they resemble flowers convincingly enough actually to attract their prey which come to collect pollen and nectar.[20][21]

Some species in Africa and Australia are able to turn black after a molt following a fire in the area to blend in with the fire ravaged landscape (fire melanism).

While mantises can bite, they have no venom. On perceiving an attack, mantises may give a deimatic display, rearing back and spreading its front legs and wings, and in some species revealing vivid colors and eyespots to startle the predator. If caught, they may slash captors with their raptorial legs. Mantises lack chemical protection, so their displays are largely bluff; many large insectivores eat mantises, including scops owls, shrikes, bullfrogs, chameleons, and milk snakes.[citation needed]

-

Adult female Iris oratoria performs a bluffing threat display, rearing back with the forelegs and wings spread and mouth opened.

-

The jeweled flower mantis, Creobroter gemmatus: the brightly coloured wings are opened suddenly in a deimatic display to startle predators.

Reproduction and life history

The mating season in temperate climates typically begins in autumn. To mate following courtship, the male usually leaps onto the female’s back, and clasps her thorax and wing bases with his forelegs. He then arches his abdomen to deposit and store sperm in a special chamber near the tip of the female’s abdomen. The female then lays between 10 and 400 eggs, depending on the species. Eggs are typically deposited in a frothy mass that is produced by glands in the abdomen. This froth then hardens, creating a protective capsule. The protective capsule and the egg mass is called an ootheca. Depending on the species, the ootheca can be attached to a flat surface, wrapped around a plant or even deposited in the ground. Despite the versatility and durability of the eggs, they are often preyed on, especially by several species of parasitic wasps. In a few species, mostly ground and bark mantids in the family Tarachodidae, the mother guards the eggs.[22] The cryptic Tarachodes maurus positions herself on bark with her abdomen covering her egg capsule, ambushing passing prey and moving very little until the eggs hatch.[7]

As in closely-related insect groups in the superorder Dictyoptera, mantises go through three life stages: egg, nymph, and adult (mantises are among the hemimetabolic insects). The nymph and adult insect are structurally quite similar, except that the nymph is smaller and has no wings or functional genitalia. The nymphs are also sometimes colored differently from the adult, and the early stages are often mimics of ants. A mantis nymph has a sturdy, flexible exoskeleton and increases in size (often changing its diet as it does so) by molting when necessary. Molting can happen from five to ten times before the adult stage is reached, depending on the species. After the final molt, most species have wings, though some species are wingless or brachypterous ("short-winged"), particularly in the female sex.[23]

In tropical species, the natural lifespan of a mantis in the wild is about 10–12 months, but some species kept in captivity have been sustained for 14 months. In colder areas, females die during the winter (as well as any surviving males).[23]

-

Mantis religiosa mating (brown male, green female)

-

Mantis laying ootheca

-

Recently laid Mantis religiosa ootheca

-

Newly hatched mantises

Sexual cannibalism

Sexual cannibalism is common among most predatory species of mantises in captivity. It has sometimes been observed in the field, where about a quarter of male-female encounters result in the male's being eaten by the female.[24][25][26] 90% of the predatory species of mantis participate in sexual cannibalism.[27] Adult males typically outnumber females at first, but their numbers may be fairly equivalent later in the adult stage,[8] possibly because females selectively eat the smaller males.[28] In Tenodera sinensis, 83% of males escaped cannibalism after an encounter with a female, but since there are multiple matings, the probability of a male's being cannibalised increases cumulatively.[25]

The female may begin feeding by biting off the male’s head (as they do with regular prey), and if mating has begun, the male’s movements may become even more vigorous in its delivery of sperm. Early researchers thought that because copulatory movement is controlled by a ganglion in the abdomen, not the head, removal of the male’s head was a reproductive strategy by females to enhance fertilization while obtaining sustenance. Later, this behavior appeared to be an artifact of intrusive laboratory observation. Whether the behavior in the field is natural, or also the result of distractions caused by the human observer, remains controversial. Mantises are highly visual organisms, and notice any disturbance occurring in the laboratory or field such as bright lights or moving scientists. Research by Liske and Davis (1984) and others found (e.g. using video recorders in vacant rooms) that Chinese mantises that had been fed ad libitum (so that they were not hungry) actually displayed elaborate courtship behavior when left undisturbed. The male engages the female in a courtship dance, to change her interest from feeding to mating.[29] Under such circumstances the female has been known to respond with a defensive deimatic display by flashing the colored eyespots on the inside of her front legs.[30]

The reason for sexual cannibalism has been debated, with some considering submissive males to be achieving a selective advantage in their ability to produce offspring. This theory is supported by a quantifiable increase in the duration of copulation among males who are cannibalized, in some cases doubling both the duration and the chance of fertilization. This is contrasted by a study where males were seen to approach hungry females with more caution, and were shown to remain mounted on hungry females for a longer time, indicating that males actively avoiding cannibalism may mate with multiple females. The same study also found that hungry females generally attracted fewer males than those that were well fed.[31] The act of dismounting is one of the most dangerous times for males during copulation, for it is at this time that females most frequently cannibalize their mates. This increase in mounting duration was thought to indicate that males are more prone to wait for an opportune time to dismount from a hungry female rather than from a satiated female that would be less likely to cannibalize her mate. Some consider this to be an indication that male submissiveness does not inherently increase male reproductive success, rather that fitter males are likely to approach a female with caution and escape.[32]

Conservation status

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (July 2015) |

With one exception (the ground mantis Litaneutria minor in Canada, where it is rare — though it is common in the United States), North American mantises are not included among threatened or endangered species, though species in other parts of the world are under threat from habitat destruction. The European mantis (Mantis religiosa) is the state insect of Connecticut, even though as a non-native species from Europe and Africa it has no special protected status. It became the state insect in October 1977.[33]

Over 20 species are native to the United States, including the common Carolina mantis, with only one native to Canada. Two species (the Chinese mantis and the European mantis) were deliberately introduced to serve as pest control for agriculture, and have spread widely in both countries.[citation needed]

In human culture

History

One of the earliest mantis references is in the ancient Chinese dictionary Erya, which gives its attributes in poetry, where it represents courage and fearlessness, and a brief description. A later text, the Jingshi Zhenglei Daguan Bencao 經史證類大觀本草 ("Great History of Medical Material Annotated and Arranged by Types, Based upon the Classics and Historical Works") from 1108, gives accurate details of the construction of the egg packages, the development cycle, anatomy and the function of the antennae.

In the Adages, [Suidas]] describes an insect like a slow-moving green locust with long front legs;[34] translating Zenobius 2.94 with the words seriphos (maybe a mantis) and graus, an old woman, implying a thin, dried-up stick of a body.[35]

Western descriptions of the biology and morphology of the mantises became more accurate in the 18th century. Roesel von Rosenhof illustrated and described mantises and their cannibalistic behaviour in the Insekten-Belustigungen (Insect Entertainments).[23]

In literature and art

Aldous Huxley made philosophical observations about the nature of death while two mantises mated in the sight of two characters in his 1962 novel Island (the species was Gongylus gongylodes). The naturalist Gerald Durrell's humorously autobiographical 1956 book My Family and Other Animals includes a four-page account of an almost evenly matched battle between a mantis and a gecko. Shortly before the fatal denouement, Durrell narrates:

he [Geronimo the gecko] crashed into the mantis and made her reel, and grabbed the underside of her thorax in his jaws. Cicely [the mantis] retaliated by snapping both her front legs shut on Geronimo's hind legs. They rustled and staggered across the ceiling and down the wall, each seeking to gain some advantage.[36]

M. C. Escher's woodcut Dream depicts a human-sized mantis standing on a sleeping bishop.[37]

In cartoons

A cultural trope imagines the female mantis as a femme fatale, devouring the male after mating. The idea is propagated in cartoons by Cable, Guy & Rodd, LeLievre, T. McCracken, and Mark Parisi among others.[38][39][40][41]

Martial arts

Two martial arts separately developed in China have movements and fighting strategies based on those of the Mantis. As one of these arts was developed in northern China, and the other in southern parts of the country, the arts are nowadays referred to (both in English and Chinese) as 'Northern Praying Mantis'[42] and 'Southern Praying Mantis'.[43] Both are very popular in China, and have also been imported to the West in recent decades.

In mythology and religion

Southern African indigenous mythology refers to the mantis as a god in Khoi and San traditional myths and practices, and the word for the mantis in Afrikaans is Hottentotsgod (literally, a god of the Khoi).[44][45] The Khoi people regarded the mantis as a god due to their posture that made it seem as if they were continually in a state of prayer with their hands together and heads bowed in worship. The word "mantis" is from the Greek for diviner, prophet or seer, as in terms like geomancy and necromancy.[46] Several ancient civilisations considered the insect to have supernatural powers: for the Greeks, it had the ability to show lost travellers the way home; in the Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead the "bird-fly" is a minor god who leads the souls of the dead to the underworld; in a list of 9th century BC Nineveh grasshoppers ("buru"), the mantis is named necromancer ("buru-enmeli") and soothsayer ("buru-enmeli-ashaga").[47][23]

As pets

Mantises are among the insects most widely kept as pets.[48][49] Because their lifespan is only about a year, mantis enthusiasts often breed the insects. At least 31 species are kept for breeding in the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and the USA.[50]

For pest control

Gardeners who prefer to avoid pesticides may encourage mantises in the hope of controlling insect pests. However, mantises do not have key attributes of biological pest control agents: they do not specialize in a single pest insect, and do not multiply rapidly in response to an increase in such a prey species, but are general predators. They therefore have "negligible value" in biological control.[51]

Notes

Sources

- Ehrmann, Reinhard (2002). Mantodea Gottesanbeterinnen der Welt (in German). Münster: Natur und Tier-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-931587-60-4.

- Klausnitzer, Bernhard (1987). Insects: Their Biology and Cultural History. Unknown. ISBN 0-87663-666-0.

- O'Toole, Christopher (2002). Firefly Encyclopedia of Insects and Spiders. Firefly. ISBN 1-55297-612-2.

- Prete, Frederick R. (1999). The Praying Mantids. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6174-1.

References

- ^ Essig, Edward Oliver (1947). College entomology. New York: Macmillan Company. pp. 124, 900. OCLC 809878.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "mantis". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Bullock, William (1812) A companion to the London Museum and Pantherion

- ^ Partington, Charles F. (1837) The British Cyclopædia of Natural History. Pub: W.S.Orr

- ^ "Praying Mantis". National Geographic Society. Retrieved January 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Otte, Daniel; Spearman, Lauren. "Mantodea Species File Online". Retrieved 2012-07-17.

- ^ a b Costa, James (2006). The other insect societies. Harvard University Press. pp. 135–136. ISBN 0-674-02163-0.

- ^ a b Capinera, John L. (2008). Encyclopedia of Entomology. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 3033–3037. ISBN 978-1-4020-6242-1.

- ^ Beier, M. (1968). "Ordnung Mantodea (Fangheuschrecken)". Handbuch der Zoologie. 4 (2): 3–12.

- ^ Klass, K.D. (1997). "External male genitalia and phylogeny of Blattaria and Mantodea". Zoologisches Forschungsinstitut; Museum Alexander Koenig.

- ^ a b c d Martill, David M.; Bechly, Günter; Loveridge, Robert F. (2007). The Crato Fossil Beds of Brazil: Window into an Ancient World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 236–238. ISBN 978-1-139-46776-6.

- ^ Ryall, Julian (25 April 2008). "Ancient Praying Mantis Found in Amber". National Geographic. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ a b Prete, Fredrick R. (1999). The praying mantids. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University. pp. 27–29, 101–103. ISBN 0-8018-6174-8.

- ^ Capinera, John L. (2008). Encyclopedia of Entomology. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-4020-6242-1.

- ^ Beckman, Noelle; Hurd, Lawrence E. (2003). "Pollen Feeding and Fitness in Praying Mantids: The Vegetarian Side of a Tritrophic Predator". Environmental Entomology. 32 (4): 881. doi:10.1603/0046-225X-32.4.881.

- ^ Yager, D; May, M (1993). "Coming in on a wing and an ear". Natural history. 102 (1): 28–33.

- ^ "Praying Mantis Uses Ultrasonic Hearing to Dodge Bats". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ O'Dea, JD (1991). "Eine zusatzliche oder alternative Funktion der 'kryptischen' Schaukelbewegung bei Gottesanbeterinnen und Stabschrecken (Mantodea, Phasmatodea)". Entomologische Zeitschrift. 101 (1–2): 25–27.

- ^ Gullan, PJ; Cranston, PS (2010). The Insects: An Outline of Entomology (4th ed.). Wiley. p. 370.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cott, Hugh (1940). Adaptive Coloration in Animals. Methuen. pp. 392–393.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|titlelink=ignored (|title-link=suggested) (help) - ^ Annandale, Nelson (1900). "Notes on the Habits and natural Surroundings of Insects made during the 'Skeat Expedition' to the Malay Peninsula, 1899–1900". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London: 837–868.

- ^ Ene, J.C. (1964). "The Distribution and Post-Embryonic Development of Tarachodes afzelli (Stal) (Mantodea : Eremiaphilidae)". Journal of Natural History. 7 (80): 493–511. doi:10.1080/00222936408651488.

- ^ a b c d Prete, Frederick R. (1999). The Praying Mantids. JHU Press. pp. 43–49. ISBN 978-0-8018-6174-1. Cite error: The named reference "Prete1999" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Lawrence (April 1992). "Sexual cannibalism in the praying mantid, Mantis religiosa: a field study". Animal Behaviour. 43 (4): 569–583.

- ^ a b Hurd, L.E. (1994). "Cannibalism Reverses Male-Biased Sex Ratio in Adult Mantids: Female Strategy against Food Limitation?". Oikos. 69 (2): 193–198.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Maxwell, Michael R. (April 1998). "Lifetime mating opportunities and male mating behaviour in sexually cannibalistic praying mantids". Animal Behaviour. 55 (4): 1011–1028.

- ^ Wilder, Shawn M.; Rypstra, Ann L.; Elgar, Mark A. (2009). "The Importance of Ecological and Phylogenetic Conditions for the Occurrence and Frequency of Sexual Cannibalism". Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 40: 21–39. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.110308.120238.

- ^ "Do Female Praying Mantises Always Eat the Males?". Entomology Today. 22 December 2013. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ Liske, E.; Davis, W.J. (1984). "Sexual behaviour of the Chinese praying mantis". Animal Behaviour. 32 (3): 916. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(84)80170-0.

- ^ Lelito, Jonathan P.; Brown, William D. (2006). "Complicity or Conflict over Sexual Cannibalism? Male Risk Taking in the Praying Mantis Tenodera aridifolia sinensis". The American Naturalist. 168 (2). doi:10.1086/505757.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Maxwell, Michael R.; Gallego, Kevin M.; Barry, Katherine L. (2010). "Effects of female feeding regime in a sexually cannibalistic mantid: Fecundity, cannibalism, and male response in Stagmomantis limbata (Mantodea)". Ecological Entomology. 35 (6): 775–87. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2311.2010.01239.x.

- ^ Lelito, Jonathan P.; Brown, William D. (2006). "Complicity or Conflict over Sexual Cannibalism? Male Risk Taking in the Praying Mantis Tenodera aridifolia sinensis". The American Naturalist. 168 (2): 263–9. doi:10.1086/505757. PMID 16874635.

- ^ "The State Insect". State of Connecticut. 2002-08-05. Retrieved 2011-01-05.

- ^ "Entomomancy". Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ Erasmus, Desiderius; Fantazzi, Charles (1992). Adages: Iivii1 to Iiiiii100. University of Toronto Press. pp. 334–335. ISBN 978-0-8020-2831-0.

- ^ Durrell, Gerald (1959) [1956]. My Family and Other Animals. Penguin Books. pp. 204–208.

- ^ "Escher, M. C., 1898–1972, Dream (Mantis religiosa). Woodengraving, April, 1935, signed". Treasures of Lauinger Library. Georgetown University. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- ^ Wade, Lisa (29 November 2010). "Shoddy Research & Cultural Tropes: The Praying Mantis". Sociological Images. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ "Praying Mantises Cartoons and Comics". CartoonStock. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ Parisi, Mark. "Praying mantis cartoons". Off the Mark Cartoons. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ McCracken, T. "Praying Mantis Should Be Gay". McHumor. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ Funk, Jon. "Praying Mantis Kung Fu". Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ Hagood, Roger D. (2012). 18 Buddha Hands: Southern Praying Mantis Kung Fu. Southern Mantis Press. ISBN 978-0-98572-401-6.

- ^ "South Africa – Religion". Countrystudies.us. Retrieved 2010-07-14.

- ^ "Afrikaans Animal Names". sanparks.org. Retrieved 2010-07-14.

- ^ "Defining Mantis". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ "Mantid". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ "PET BUGS: Kentucky arthropods". University of Kentucky. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ Van Zomeren, Linda. "European Mantis". Keeping Insects. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ "Breeding reports: 1st July 2013-1st October 2013" (PDF). UK Mantis Forums Newsletter, Issue 12. UK Mantis Forums (group). October 2013. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ Doutt, R. L. "The Praying Mantis (Leaflet 21019" (PDF). University of California Division of Agricultural Sciences. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

External links

- Mantis Study Group Information on mantids, scientific article phylogenetics and Evolution.