Flat Earth

The notion of a flat Earth refers to the idea that the inhabited surface of Earth is flat, rather than curved (see Spherical Earth). It is believed to have been prevalent up to and including early Classical Antiquity, and is evidenced in early Greek maps like those of Anaximander and Hecataeus. The first person known to have advocated a spherical shape of the Earth is Pythagoras (6th century BC).

By the time of Pliny the Elder (1st century) at the latest, however, the Earth's spherical shape was generally acknowledged among the learned in the western world. At that time Ptolemy derived his maps from a curved globe and developed the system of latitude and longitude (see clime). His writings remained the basis of European astronomy throughout the Middle Ages, although Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages (ca. 3rd to 7th centuries) saw occasional arguments in favour of a flat Earth from a few Christian authors, usually on theological grounds.

The modern misconception that people of the Middle Ages believed that the Earth was flat first entered the popular imagination in the nineteenth century.

Antiquity

Belief in a flat Earth is found in mankind's oldest writings. In early Mesopotamian thought, the world was portrayed as a flat disk floating in the ocean, and this forms the premise for early Greek maps like those of Anaximander and Hecataeus.

By classical times an alternative idea, that Earth was spherical, had appeared. This was espoused by Pythagoras apparently on aesthetic grounds, as he also held all other celestial bodies to be spherical. Aristotle provided observational evidence for the spherical Earth.[1], in that travelers going south see southern constellations rise higher above the horizon. This is only possible if their horizon is at an angle to northerners' horizon. Thus Earth's surface cannot be flat.[2] Also, the border of the shadow of Earth on the Moon during the partial phase of a lunar eclipse is always circular, no matter how high the Moon is over the horizon. Only a sphere casts a circular shadow in every direction, whereas a circular disk casts an elliptical shadow in most directions.[3]

The Earth's circumference was measured around 240 BC by Eratosthenes. Eratosthenes knew that in Syene (now Aswan), in Egypt, the Sun was directly overhead at the summer solstice, while he estimated that a shadow cast by the Sun at Alexandria was 1/50th of a circle. He estimated the distance from Syene to Alexandria as 5,000 stades, and estimated the Earth's circumference was 250,000 stades and a degree was 700 stades (implying a circumference of 252,000 stades).[4] Eratosthenes used rough estimates and round numbers, but depending on the length of the stadion, his result is within a margin of between 2% and 20% of the actual circumference, 40,008 kilometres. Note that Eratosthenes could only measure the circumference of the Earth by assuming that the distance to the Sun is so great that the rays of sunlight are essentially parallel. A similar measurement, reported in a Chinese mathematical treatise the Zhoubi suanjing (1st c. BC), was used to measure the distance to the Sun by assuming that the Earth was flat.[5]

During this period, Earth was generally thought of as divided into zones of climate, with a frigid clime at the poles, a deadly torrid clime near the equator, and a mild and habitable temperate clime between the two. It was thought that the different temperatures of these zones were related with proximity to the sun. They were wrong in believing that no one could cross the torrid clime and reach the unknown lands on the other half of the globe. At the time, these imagined lands as well as their inhabitants were both called antipodes.[6]

Lucretius (1st. c. BC) opposed the concept of a spherical Earth, because he considered the idea of antipodes absurd. But by the 1st century AD, Pliny the Elder was in a position to claim that everyone agrees on the spherical shape of Earth (Natural History, 2.64), although there continued to be disputes regarding the nature of the antipodes, and how it is possible to keep the ocean in a curved shape. Interestingly, Pliny as an "intermediate" theory considers also the possibility of an imperfect sphere, "shaped like a pinecone". (Natural History, 2.65)

In the Second century the Alexandrian astronomer, Ptolemy, advanced many arguments for the sphericity of the Earth. Among them was the observation that when sailing towards mountains, they seem to rise from the sea, indicating that they were hidden by the curved surface of the sea.[7]

In late antiquity such widely read encyclopedists as Macrobius (4th c.) and Martianus Capella (5th c.) discussed the circumference of the sphere of the Earth, its central position in the universe, the difference of the seasons in northern and southern hemispheres, and many other geographical details.[8] In his commentary on Cicero's Dream of Scipio, Macrobius described the Earth as a globe of insignificant size in comparison to the remainder of the cosmos.[9]

The Early Church

From Late Antiquity, and thus from the beginnings of Christian theology, knowledge of the sphericity of the Earth had become widespread.[10] There was, however, some debate concerning the possibility of the inhabitants of the antipodes: people imagined as separated by an impassable torrid clime were difficult to reconcile with the Christian view of a unified human race descended from one couple and redeemed by a single Christ.

Saint Augustine (354–430) argued against people inhabiting the antipodes:

- But as to the fable that there are Antipodes, that is to say, men on the opposite side of the earth, where the sun rises when it sets to us, men who walk with their feet opposite ours, that is on no ground credible. And, indeed, it is not affirmed that this has been learned by historical knowledge, but by scientific conjecture, on the ground that the earth is suspended within the concavity of the sky, and that it has as much room on the one side of it as on the other: hence they say that the part which is beneath must also be inhabited. But they do not remark that, although it be supposed or scientifically demonstrated that the world is of a round and spherical form, yet it does not follow that the other side of the earth is bare of water; nor even, though it be bare, does it immediately follow that it is peopled.[11]

Since these people would have to be descended from Adam, they would have had to travel to the other side of the Earth at some point; Augustine continues:

- ... it is too absurd to say, that some men might have taken ship and traversed the whole wide ocean, and crossed from this side of the world to the other, and that thus even the inhabitants of that distant region are descended from that one first man.

Augustine does not deny the idea of a round Earth. However, the phrase "although it be supposed or scientifically demonstrated that the world is of a round and spherical form" (Latin: etiamsi figura conglobata et rotunda mundus esse credatur sive aliqua ratione monstretur) suggests that he was sceptical of the claims that the Earth was round, and perhaps that others were as well. It is worth noting, though, that Augustine explicitly describes the Earth as a globe in other writings.[12]

A few Christian authors directly opposed the round Earth:

- Lactantius (245–325) called it "folly" because people on a sphere would fall down.

- Saint Cyril of Jerusalem (315–386) saw Earth as a firmament floating on water (though the relevant quotation is found in the course of a sermon to the newly baptized, and it is unclear whether he was speaking poetically or in a physical sense);

- Saint John Chrysostom (344–408) saw a spherical Earth as contradictory to scripture;

- Diodorus of Tarsus (d. 394) also argued for a flat Earth based on scriptures; however, Diodorus' opinion on the matter is known to us only by a criticism of it by Photius.[13];

- Severian, Bishop of Gabala (d. 408), wrote: "The earth is flat and the sun does not pass under it in the night, but travels through the northern parts as if hidden by a wall".[14]

- The Egyptian monk Cosmas Indicopleustes (547) in his Topographia Christiana, where the Covenant Ark was meant to represent the whole universe, argued on theological grounds that the Earth was flat, a parallelogram enclosed by four oceans.

At least one early Christian writer, Basil of Caesarea (329–379), believed the matter to be theologically irrelevant.[15]

Different historians have maintained that these advocates of the flat Earth were either influential (a view typified by Andrew Dickson White) or relatively unimportant (typified by Jeffrey Russell) in the later Middle Ages. The scarcity of references to their beliefs in later medieval writings convinces most of today's historians that their influence was slight.

The Middle Ages

Early Middle Ages

With the end of Roman civilization, Western Europe entered the Middle Ages with great difficulties that affected the continent's intellectual production. Most scientific treatises of classical antiquity (in Greek) were unavailable, leaving only simplified summaries and compilations. Still, the dominant textbooks of the Early Middle Ages supported the sphericity of the Earth. For example: many early medieval manuscripts of Macrobius include maps of the Earth, including the antipodes, zonal maps showing the Ptolemaic climates derived from the concept of a spherical Earth and a diagram showing the Earth (labeled as globus terrae, the sphere of the Earth) at the center of the hierarchically ordered planetary spheres.[16] Images of some of these features can be found in: Dream of Scipio#Gallery.

Europe's view of the shape of the Earth in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages may be best expressed by the writings of early Christian scholars:

- Boethius (c. 480 – 524), who also wrote a theological treatise On the Trinity, repeated the Macrobian model of the Earth as an insignificant point in the center of a spherical cosmos in his influential, and widely translated, Consolation of Philosophy.[17]

- Bishop Isidore of Seville (560 – 636) taught in his widely read encyclopedia, the Etymologies, that the Earth was round. His meaning was ambiguous and some writers think he referred to a disc-shaped Earth; his other writings make it clear, however, that he considered the Earth to be globular.[18] He also admitted the possibility of people dwelling at the antipodes, considering them as legendary[19] and noting that there was no evidence for their existence.[20] Isidore's disc-shaped analogy continued to be used through the Middle Ages by authors clearly favouring a spherical Earth, e.g. the 9th century bishop Rabanus Maurus who compared the habitable part of the northern hemisphere (Aristotle's northern temperate clime) with a wheel, imagined as a slice of the whole sphere.

- The monk Bede (c.672 – 735) wrote in his influential treatise on computus, The Reckoning of Time, that the Earth was round, explaining the unequal length of daylight from "the roundness of the Earth, for not without reason is it called 'the orb of the world' on the pages of Holy Scripture and of ordinary literature. It is, in fact, set like a sphere in the middle of the whole universe." (De temporum ratione, 32). The large number of surviving manuscripts of The Reckoning of Time, copied to meet the Carolingian requirement that all priests should study the computus, indicates that many, if not most, priests were exposed to the idea of the sphericity of the Earth.[21] Ælfric of Eynsham, paraphrased Bede into Old English, saying "Now the Earth's roundness and the Sun's orbit constitute the obstacle to the day's being equally long in every land."[22]

- Bishop Vergilius of Salzburg (c.700 – 784) is sometimes cited as having been persecuted for teaching "a perverse and sinful doctrine ... against God and his own soul" regarding the sphericity of the earth. Pope Zachary decided that "if it shall be clearly established that he professes belief in another world and other people existing beneath the earth, or in [another] sun and moon there, thou art to hold a council, and deprive him of his sacerdotal rank, and expel him from the church."[23] The issue involved was not the sphericity of the Earth itself, but whether people living in the antipodes were not descended from Adam and hence were not in need of redemption. Vergilius succeeded in freeing himself from that charge; he later became a bishop and was canonised in the thirteenth century.[24]

A recent study of medieval concepts of the sphericity of the Earth noted that "since the eighth century, no cosmographer worthy of note has called into question the sphericity of the Earth."[25] Of course it was probably not the few noted intellectuals who defined public opinion. It is difficult to tell what the wider population may have thought of the shape of the Earth – if they considered the question at all. It may have been as irrelevant to them as the Heisenberg uncertainty principle is to most of our contemporaries.

Later Middle Ages

By the 11th century, Europe had learned of Islamic astronomy. Around 1070 started the Renaissance of the 12th century, featuring an intellectual revitalization of Europe with strong philosophical and scientific roots, and increased appetite for the study of nature. By then, abundant records suggest that any doubts that Europeans may had had in earlier times in regard to the spherical shape of the Earth were generally eliminated.

Hermannus Contractus (1013–1054) was among the earliest Christian scholars to estimate the circumference of Earth with Eratosthenes' method. Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), the most important and widely taught theologian of the Middle Ages, believed in a spherical Earth; and he even took for granted his readers also knew the Earth is round.[26] Lectures in the medieval universities commonly advanced evidence in favor of the idea that the Earth was a sphere.[27] Also, "On the Sphere of the World", the most influential astronomy textbook of the 13th century and required reading by students in all Western European universities, described the world as a sphere.

The late development of European vernacular languages also provides some evidence to the contention that the spherical shape of the Earth was common knowledge outside academic circles. At the time, scholarly work was typically written in Latin. Works written in a native dialect or language (such as Italian or German) were generally intended for a wider audience.

Dante's Divine Comedy, the last great work of literature of the Middle Ages, written in Italian, portrays Earth as a sphere. Also, the Elucidarium of Honorius Augustodunensis (c. 1120), an important manual for the instruction of lesser clergy which was translated into Middle English, Old French, Middle High German, Old Russian, Middle Dutch, Old Norse, Icelandic, Spanish, and several Italian dialects, explicitly refers to a spherical Earth. Likewise, the fact that Bertold von Regensburg (mid-13th century) used the spherical Earth as a sermon illustration shows that he could assume this knowledge among his congregation. The sermon was held in the vernacular German, and thus was not intended for a learned audience.

Reinhard Krüger, a professor for Romance literature at the University of Stuttgart (Germany), has discovered more than 100 medieval latin and vernacular writers from the late antiquity to the 15th century who were all convinced that the earth was round like a ball. However, as late as 1400s, the Spanish theologian Tostatus still disputed the existence of any inhabitants at the antipodes[28]. From a European perspective, Portuguese exploration of Africa and Asia and Spanish explorations in the Americas in the 15th century and finally Ferdinand Magellan's circumnavigation of the earth brought the experimental proofs for the global shape of the earth.

Modern times

The common misconception that people, especially the Christian Church, before the age of exploration believed that Earth was flat entered the popular imagination after Washington Irving's publication of The Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus in 1828. In the United States, this belief persists in the popular imagination, and is even repeated in some widely read textbooks. Previous editions of Thomas Bailey's The American Pageant stated that "The superstitious sailors ... grew increasingly mutinous...because they were fearful of sailing over the edge of the world"; however, no such historical account is known.[29] Actually, sailors were probably among the first to know of the curvature of Earth from daily observations — seeing how shore landscape features (or masts of other ships) gradually descend/ascend near the horizon.

During the 19th century, the Romantic conception of a European "Dark Age" gave much more prominence to the Flat Earth model than it ever possessed historically.

The widely circulated woodcut of a man poking his head through the firmament of a flat Earth to view the mechanics of the spheres, executed in the style of the 16th century cannot be traced to an earlier source than Camille Flammarion's L'Atmosphère: Météorologie Populaire (Paris, 1888, p. 163) [14]. The woodcut illustrates the statement in the text that a medieval missionary claimed that "he reached the horizon where the Earth and the heavens met", an anecdote that may be traced back to Voltaire, but not to any known medieval source. In its original form, the woodcut included a decorative border that places it in the 19th century; in later publications, some claiming that the woodcut did, in fact, date to the 16th century, the border was removed. Flammarion, according to anecdotal evidence, had commissioned the woodcut himself. In any case, no source of the image earlier than Flammarion's book is known.

In Inventing the Flat Earth: Columbus and Modern Historians, Jeffrey Russell (professor of history at University of California, Santa Barbara) claims that the Flat Earth theory is a fable used to impugn pre-modern civilization, especially that of the Middle Ages in Europe. Today essentially all professional medievalists agree with Russell that the "medieval flat Earth" is a nineteenth-century fabrication, and that the few verifiable "flat Earthers" were the exception.

Modern Flat Earthers

Modern people who do not accept the spherical Earth and base this opinion on Scripture do not represent a continuing school of Biblical exegesis. Some Christians, following what they saw as a literal interpretation of scripture, tried to restore public faith in Biblical cosmology. In 1898 during his solo circumnavigation of the world Joshua Slocum encountered such a group in the Transvaal Republic. President Kruger berated him, telling him "you don't mean around the world; it is impossible! You mean in the world!"[30] The last known group, the Flat Earth Society, kept the concept alive and at one time claimed a few thousand followers. The society declined in the 1990s following a fire at its headquarters in California and the death of its last president, Charles K. Johnson, in 2001.[31] They still maintain a website and forum.

The Flat Earth in popular culture

In fiction

- E. A. Abbott's satire Flatland (1884) is set in an entirely two-dimensional world.

- In Rudyard Kipling's The Village that Voted the Earth was Flat, the unnamed narrator and some friends are unjustly fined for a minor offence by a crooked village magistrate and his accomplices in the police. By way of revenge, they spread the rumor that a Parish Council meeting had voted in favor of a flat Earth. The village is ridiculed in the press, and a popular song entitled The Village that Voted the Earth was Flat sweeps the nation. When the narrator visits the House of Commons and observes the Members of Parliament singing the song, he reflects that he may have gone too far.

- In L. Frank Baum's Mother Goose in Prose, the Three Wise Men of Gotham make their journey to decide whether the earth is flat, spherical or hollow.

- In some of J.R.R. Tolkien's writings, his fantasy world of Arda is conceived as a world which was originally flat, but became spherical at the time of the Fall of Númenor.

- In C.S. Lewis' The Voyage of the Dawn Treader it is implied that the fictional world of Narnia is flat, or at least that its inhabitants perceive it to be.

- Terry Pratchett's Discworld novels (1983 onwards) are set on a disc-shaped world resting on the backs of four huge elephants which are in turn standing on the back of an enormous turtle. He had earlier explored a similar setting in Strata (1981).

- In the fictional text adventure universe of Zork, Quendor is located on a flat planet held up by a giant Brogmoid.

In other contexts

- Thomas Friedman uses the metaphor of a "flat Earth" to describe the leveling of the world economic stage in his best-selling book, The World is Flat.

- The Spanish songwriter Quimi Portet released, in 2004, an album called "La Terra és Plana" (which in Catalan means "The Earth is Flat") and a single with the same title.

- Robert McKimson's 1951 cartoon Hare We Go pairs up Bugs Bunny with Christopher Columbus. It opens with Columbus arguing about the shape of the world with the king of Spain, who insists that it's flat.

- Monty Python's film The Meaning of Life contains a skit, The Crimson Permanent Assurance, in which a pirate office building falls off the edge of the world.

- The Golden Sun video game series is set in a flat world called Weyard.

- Ernie Kovacs, in a radio skit called "Mr. Question Man", put a twist on the usual stereotyped skepticism of the round Earth. An alleged listener's question was, "If the Earth is round, why don't people fall off?" Kovacs' answer: "What you've stated is a common misconception. People are falling off all the time!"

- Flip Wilson, in an old standup routine playing Christopher Columbus, put a different spin on the old joke. Arguing with someone over whether to take his famous voyage, he was told, "Don't you know the world is square?" He replied, "It sure is!"

- In Cow & Chicken after Chicken and Cow were playing with the globe, their parents confiscated the globe and taught them that the Earth is flat like a pancake.

- Our Flat Earth is the name of a Chicago late night comedy show that uses Flat Earth theory to parody intelligent design and religious conservatism.

Notes

- ^ G. E. R. Lloyd, Aristotle: The Growth and Structure of His Thought, (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1968), pp. 162-164.

- ^ Aristotle, De caelo, 297b24-31

- ^ Aristotle, De caelo, 297b31-298a10

- ^ Albert Van Helden, Measuring the Universe: Cosmic Dimensions from Aristarchus to Halley, (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Pr., 1985, pp. 4-5. ISBN 0-226-84882-5

- ^ G. E. R. Lloyd, Adversaries and Authorities: Investigations into Ancient Greek and Chinese Science, (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1996), pp. 59-60.

- ^ Alfred Hiatt, "Blank Spaces on the Earth," The Yale Journal of Criticism, 15, (2002): 223–250; Michael Livingston, Modern Medieval Map Myths: The Flat World, Ancient Sea-Kings, and Dragons, 2002.

- ^ Ptolemy, Almagest, I.4, quoted in Edward Grant, A Source Book in Medieval Science, (Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Pr., 1974), pp. 63-4

- ^ Macrobius, Commentary on the Dream of Scipio, V.9-VI.7, XX.18-24, trans. W. H. Stahl, (New York: Columbia Univ. Pr., 1952; Martianus Capella, The Marriage of Philology and Mercury, VI.590-610, trans. W. H. Stahl, R. Johnson, and E. L. Burge, (New York: Columbia Univ. Pr., 1977).

- ^ Macrobius, Commentary on the Dream of Scipio, transl. W. H. Stahl, (New York: Columbia Univ. Pr., 1952), chaps. v-vii, (pp. 200-212).

- ^ But note that the (spherical) globus cruciger, as depicted on coins by Theodosius II for example, may symbolize the entire cosmos, not just Earth.

- ^ De Civitate Dei, Book XVI, Chapter 9 — Whether We are to Believe in the Antipodes, translated by Rev. Marcus Dods, D.D.; from the Christian Classics Ethereal Library at Calvin College

- ^ In his commentary on the Literal Meaning of Genesis, Augustine treats the Earth as a globe: "At the time when it is night with us, the Sun is illuminating with its presence [other parts of the world....] For the whole 24 hours of the Sun’s circuit there is always day in one place and night in another." "Although water still covered all the Earth, there was nothing to prevent the massive watery sphere from day on one side by the presence of light, and on the other side, night by the absence of light." (Augustine, Literal Meaning of Genesis, 30, 33) [1]

- ^ J.L.E. Dreyer, A History of Planetary Systems from Thales to Kepler. (1906); unabridged republication as A History of Astronomy from Thales to Kepler (New York: Dover Publications, 1953).

- ^ J.L.E. Dreyer, A History of Planetary Systems, (1906)

- ^ Saint Basil the Great, Hexaemeron 9 - HOMILY IX - "The creation of terrestrial animals", Holy Inocents Orthodox Church.[2]

- ^ B. Eastwood and G. Graßhoff, Planetary Diagrams for Roman Astronomy in Medieval Europe, ca. 800-1500, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, 94, 3 (Philadelphia, 2004), pp. 49-50.

- ^ S. C. McCluskey, Astronomies and Cultures in Early Medieval Europe, (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1998), pp. 114, 123.

- ^ Isidore, Etymologiae, XIV.ii.1[3]; Wesley M. Stevens, "The Figure of the Earth in Isidore's De natura rerum", Isis, 71(1980): 268-277.

- ^ Isidore, Etymologiae, XIV.v.17[4].

- ^ Isidore, Etymologiae, IX.ii.133[5].

- ^ Faith Wallis, trans., Bede: The Reckoning of Time, (Liverpool: Liverpool Univ. Pr., 2004), pp. lxxxv-lxxxix.

- ^ Ælfric of Eynsham, On the Seasons of the Year, Peter Baker, trans. [6]

- ^ MGH, Epistolae Selectae 1, 80, pp. 178-9.[7]; translation in M. L. W. Laistner, Thought and Letters in Western Europe: A.D. 500 to 900, 2nd. ed., (Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Pr., 1955), pp. 184-5.

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia.[8]

- ^ Klaus Anselm Vogel, "Sphaera terrae - das mittelalterliche Bild der Erde und die kosmographische Revolution," PhD dissertation Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, 1995, p. 19.[9]

- ^ When Aquinas wrote his Summa, at the very beginning, the idea of a round earth was the example used when he wanted to show that fields of science are distinguished by their methods rather than their subject matter... "Sciences are distinguished by the different methods they use. For the astronomer and the physicist both may prove the same conclusion - that the earth, for instance, is round: the astronomer proves it by means of mathematics, but the physicist proves it by the nature of matter. [10]"

- ^ E. Grant, Planets. Stars, & Orbs: The Medieval Cosmos, 1200-1687, (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1994), pp. 626-630.

- ^ A. D. White, A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom, (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1896)[11].

- ^ James. W. Loewen, Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your History Textbook Got Wrong, (Touchstone Books, 1996), p. 56

- ^ Joshua Slocum, Sailing Alone Around the World, (New York: The Century Company, 1900), chaps. 17-18.[12]

- ^ Donad E. Simanek, The Flat Earth.[13]

See also

- Scientific mythology

- Islam and flat-earth theories

- Antipodes

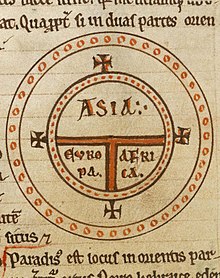

- T and O map

- Hollow earth

- The Discworld series, written by Terry Pratchett

- The Flat Earth Society

Further reading

- Aufgebauer, Peter 2006. "Die Erde ist eine Scheibe" - Das mittelalterliche Weltbild in der Wahrnehmung der Neuzeit, in: Geschichte in Wissenschaft und Unterricht, Heft 7/8, 2006, S. 427-441.

- Gingerich, O. 1992. "Astronomy in the age of Columbus". Scientific American, 267(5), (November), 66-71. (An expansion of some of Russell’s historical material, with comments on the subsequent Copernican Revolution.)

- Gould, S.J. 1996. "The late birth of a flat Earth". In: Dinosaur in a haystack, Jonathan Cape, London, 3-40. (Reprinted from "The persistently flat Earth", Natural History, 103, March 1994, 12-19. Draws extensively from Russell and discusses the way a desire to see "progress" has led to the rewriting of history and to the advocacy of a warfare between science and religion).

- Jones, Charles W. 1934. "The Flat Earth". Thought, 9, 296–307. An early critique of the "Flat Earth thesis" by an expert on Bede and Early Medieval England.

- Krüger, Reinhard 2000a. Das Überleben des Erdkugelmodells in der Spätantike (ca.60 v.u.Z. - ca 550) (Eine Welt ohne Amerika II), Weidler, Berlin.

- Krüger, Reinhard 2000b. Das lateinische Mittelalter und die Tradition des antiken Erdkugelmodells (ca. 550 - 1080) (Eine Welt ohne Amerika III), Weidler, Berlin.

- Russell, Jeffrey Burton 1991. Inventing the Flat Earth. Columbus and modern historians, Praeger, New York, Westport, London 1991, see his summary.

- Simek, Rudolf 1992. Erde und Kosmos im Mittelalter. Das Weltbild vor Kolumbus, München 1992.

- Tyler, D.J. 1996. "The impact of the Copernican Revolution on biblical interpretation". Origins, July (No. 21), 2-8. (Discusses the "language of appearance" used in the Bible and the way hermeneutical issues were clarified by the Copernican revolution. The principles developed in this article are directly applicable to any claim that the Bible "teaches a Flat Earth".)

- Vogel, Klaus Anselm 1995. Sphaera terrae: Das mittelalterliche Bild der Erde und die kosmographische Revolution, phil. Diss., Göttingen 1995. online

- White, Andrew D. 1896. A History of The Warfare Of Science With Theology in Christendom.

- Wolf, Jürgen 2004. Die Moderne erfindet sich ihr Mittelalter - oder wie aus der 'mittelalterlichen Erdkugel' eine 'neuzeitliche Erdscheibe' wurde (Colloquia academica Nr. 5), Stuttgart, Steiner.

External links

- 7000 Years of Thinking Regarding Earth's Shape

- You say the earth is round? Prove it (from The Straight Dope)

- Science & Technology News - 'Debunking The Flat Earth Myth against Christianity'

- Flat Earth Fallacy

- Zetetic Astronomy, or Earth Not a Globe by Parallax (Samuel Birley Rowbotham (1816-1884)) at sacred-texts.com

- Christian Topography by Cosmas Indiopleustes at sacred-texts.com

- The Fiction of Washington Irving