Machine pistol

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (August 2013) |

A machine pistol is typically a handgun-style,[1] magazine-fed, self-loading firearm, capable of fully automatic or burst fire, and chambered for pistol cartridges. The term is a literal translation of Maschinenpistole, the German term for a hand-held automatic weapon firing pistol cartridges.

While the dividing line between machine pistols and compact submachine guns is hard to draw, the term "submachine gun" usually refers to carbines designed for automatic fire of pistol cartridges, while the term "machine pistol" usually refers to a weapon built up from a semi-automatic pistol design, through use of a modified "fire control group", and which usually includes a modified "disconnector" and a selector which either enables (semi-automatic mode) or inhibits (fully automatic mode) the conventional, semi-automatic operation of the "disconnector".

Machine pistols are generally more compact to be concealable and can be operated one-handed, while submachine guns are usually designed to be two-handed and tend to have longer barrels for better accuracy. A current production machine pistol is the Glock 18, which is a relatively simple enhancement of the Glock 17, upon which it is largely based. Unlike firearms which were designed from the ground-up to be selective-fire, the Glock 18 includes only semi-automatic and fully automatic modes, and does not have the 3-shot "burst" count capability which is quite common on many selective-fire weapons.

As a small, concealable weapon with a high rate of fire, machine pistols have numerous applications. Bodyguards from government or private agencies sometimes carry concealed machine pistols when they are protecting high-risk VIPs. Criminal gang members such as narcotics traffickers also use machine pistols, often cheaper guns such as the MAC-10 or the Tec-9 which have been illegally converted to fire in a fully automatic fashion. In a law enforcement context, machine pistols may be used by tactical police units such as SWAT teams or hostage rescue teams which are operating inside buildings and other cramped spaces, although they tend to use submachine guns instead.

In a military setting, some countries issue machine pistols as personal defense side arms to infantry, paratroopers, artillery crews, helicopter crews or tank crews. They have also been used in close quarters combat (CQC) settings where a small weapon is needed (e.g., by special forces attacking buildings or tunnels). In the 2000s, the machine pistol started to be supplanted by the personal defense weapon: a compact, fully automatic submachine gun-like firearm which fires high-velocity armor-piercing rounds instead of pistol ammunition.

History and variants

1918–1960s

In World War I, in the last year of the conflict, the Germans developed the Bergmann MP 18, a small, hand-held automatic weapon with a rifle-like form (including a wooden stock). Even though it looked like a small rifle, it used 9 mm pistol ammunition, which introduced the idea of an automatic weapon that fired pistol rounds. While heavy machine guns such as the Maxim gun and the Vickers gun were fearsome defensive weapons in a built-up emplacement, they were very hard to move to a new position if the army had advanced to a new area, or if it had to fall back. The German Army recognized that to break the stalemate of trench warfare, a light, hand-held automatic weapon was needed that would enable individual soldiers to move with the gun to new firing positions.

The Germans also did experiments with converting various types of pistols to machine pistols (Reihenfeuerpistolen, literally "row-fire pistols"). The Luger P08 long barrel pistol was issued in World War I to German artillery crews. It was manufactured with a longer barrel as it was recognized that artillery crew needed a lighter weapon than a rifle but with similar accuracy to defend themselves. It had a newly developed pistol cartridge, the 9mm Parabellum, which was designed for low recoil without sacrificing penetration and stopping power. Although not armour piercing, the bullet more than sufficed for the time.

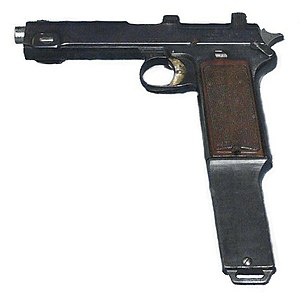

Along with the Luger, the Mauser C96 pistol was modified to fire in a fully automatic mode. It was produced in 1896, and was one of the first commercially successful and practical semi-automatic pistols. In the late 1920s, Spanish gunmakers introduced "selective fire" copies of the C96 with detachable magazines, and in the early 1930s Mauser engineers introduced the model 711 and 712 Schnellfeuer variants, which included a fire selector mechanism allowing fully automatic fire at a rate of 1000 rounds/minute. Due to the weapon's light barrel, the fully automatic rate of fire could only be used for short bursts.

In the Prohibition era, a San Antonio gunsmith, Hyman S. Lebman converted at least five Colt M1911s chambered in .38 Super and .45 ACP to fire fully automatic. These were true hand-held machine pistols, which were fitted with Thompson submachine gun Model 1921 vertical grips on their dust covers, an extended barrel with muzzle brakes similar to the Thompson's, an extended 20-round magazine. They could only be fired on fully automatic. Lebman then sold these "baby machine guns" to Prohibition Era gangsters, the most notable being John Dillinger and Baby Face Nelson.

In World War II, the Polish resistance produced a crude, simply constructed machine pistol called the Bechowiec-1. The weapon was designed in 1943 by engineer Henryk Strąpoć and produced in several underground facilities; the name is a reference to the resistance fighters who used the weapon.

The APS Stechkin is a Russian selective-fire machine pistol introduced into the Russian army in 1951. Like the other common Russian army pistol of this era, the Makarov, the Stechkin uses a simple unlocked blow-back mechanism and the double-action trigger. In addition, the Stechkin APS has an automatic fire mode, which is selected using the safety lever. In burst or automatic fire, the pistol should be fitted with the wooden shoulder stock; otherwise, the weapon quickly becomes uncontrollable.

The Stechkin was intended as a side arm for artillery soldiers and tank crews. In practice, it earned a strong following in the ranks of political and criminal police, special forces and the like. Many KGB and GRU operatives favored the Stechkin for its power and magazine capacity. Though somewhat heavy and cumbersome, it was the only "high-powered" alternative to the modest-performing PM. As a pistol, the Stechkin is being slowly replaced by the Yarygin PYa; as a PDW, it was replaced by the AKS-74U compact assault rifle, now widely used in law enforcement.

1970s–1980s

Since it is difficult to control machine pistols when they are fired in full automatic mode, in the 1970s, some manufacturers developed an "intermittent-fire" setting that fires a burst of three shots instead of a full-automatic stream. In the 1970s, the Italian Beretta company developed the Beretta Model 93R, a selective-fire machine pistol meant for police and military use. It offered extra firepower in a small package and is suited for concealed carry purposes such as VIP protection, or for close quarters maneuvers such as room-to-room searches. A selector switch and the foldable foregrip allows the pistol to fire three-round bursts with each pull of the trigger for a cyclic rate of 1100 rounds per minute. The designers limited it to fixed three-round bursts to allow it to be more easily controlled.

Another machine pistol using the three shot burst system is the Heckler & Koch VP70. It will only fire three-round bursts with the stock attached. It is a 9 mm, 18-round, double action only, semi-automatic/three-round burst capable polymer frame pistol manufactured by German arms firm Heckler & Koch GmbH; the VP designation stands for Volkspistole ("The people's pistol"), and the designation 70 was for the year of the first edition: 1970. It was the first polymer-framed pistol, predating the Glock 17. The stock incorporates a selector switch that allows selective fire. Cyclic rounds per minute for the three-round bursts is 2200 rpm. The VP70 uses a spring-loaded striker like a Glock, instead of a conventional firing pin. It is double action only, so the trigger pull is relatively heavy. Despite the VP70's potential, it was never adopted by the Bundeswehr.

The MAC-10 (also known as the "Ingram Model 10") and MAC-11 (also called the "Ingram Model 11") were 1970s blowback designed weapons with the magazine in the pistol grip and a fire selector switch. The .45 ACP MAC-10 had a 1145 round-per-minute rate of fire, and the 9×19mm version 1090 rounds-per-minute. The MAC-11 could fire 1200 rounds-per-minute with its 9×17mm .380 ACP cartridges. The guns were designed by Gordon Ingram and Military Armament Corporation in the US. The weapons used in special ops and clandestine applications in Vietnam and by Brazilian anti-terrorist units. It could be fitted with a silencer using its threaded barrel. While some sources call the MAC-10 and MAC-11 machine pistols,[2] the guns are also referred to as compact submachine guns.

The Stechkin APS made a comeback in the late 1970s, when Russian Spetsnaz special forces units in Afghanistan used suppressor-equipped machine pistols for clandestine missions in enemy territory, such as during the Soviet war in Afghanistan.

In the 1980s, some machine pistols, such as the Glock 18 were made with vents or cuts that run across the top of the barrel. These vents act as a compensator, thus counteracting the tendency of machine pistols to rise when fired in automatic mode. The Glock 18 is a selective-fire variant of the Glock 17, developed in 1986 at the request of the Austrian counter-terrorist unit EKO Cobra. The Glock 18 is not legally available to the civilian market.[citation needed] This machine pistol-class firearm has a lever-type fire-control selector switch, installed on the left side of the slide, in the rear, serrated portion (selector lever in the bottom position for continuous fire, top setting for single fire). The firearm is typically used with an extended 33-round capacity magazine. The pistol's rate of fire in fully automatic mode is approximately 1100–1200 rounds/min.

The Micro Uzi is a scaled-down version of the Uzi, first introduced in 1983. It is 460 mm (18.11 inches) long with the stock extended, and just 250 mm (9.84 inches) long with the stock folded. Its barrel length is 117 mm and its muzzle velocity is 350 m/s. After its early 1980s introduction, it was used by the Israeli Isayeret and the US Secret Service. In the 1990s and 2000s, Israeli counter-terror units such as the YAMAM used the 33-round Glock 18 magazine with their Para Micro Uzi machine pistols. The UZI submachine gun upon which the Micro-Uzi is based was developed in Israel by Uziel Gal in the late 1940s. Micro-Uzis are available in open-bolt or closed-bolt versions. The weapon has an additional tungsten weight on the bolt to slow the rate of fire, which would otherwise make such a lightweight weapon uncontrollable.[3]

There is also a rare version of the Česká Zbrojovka CZ75 that is fully automatic with a longer barrel and three vent ports on the elongated part. This machine pistol has a horizontal rail in front of the trigger guard through which a spare magazine can be attached and be used as a foregrip for better control during full automatic firing. This weapon is still produced by CZ but is only available to military and law enforcement personnel.

In 1988, an unusually designed US 9mm machine pistol named the Calico M950 was introduced. Unlike most machine pistols, which use magazines in the pistol grip or in a vertical box, the M950 uses a 50-round or 100-round helical magazine which is mounted parallel to the barrel. To get a sense of how the helical magazine appears, and how it is mounted, one can imagine a machine pistol with a bulky optical scope mounted on the picatinny rail on the top of the weapon.

The Saturn machine pistol is of Colombian origin, and it is designed for clandestine operations.[4] The weapon is twin barreled and is fed from a dual magazine. The weapon has one bolt with two firing pins. An unusual dual barrel suppressor can be used on this firearm.

1990s–2000s

During the 1990s, the Russian Stechkin APS was once again put into service, as a weapon for VIP bodyguards and for anti-terrorist hostage rescue teams that needed the capability for full automatic fire in emergencies. In the 1990s and 2000s the personal defense weapon, a compact submachine gun-like firearm which can fire armor-piercing, higher-powered ammunition began to replace the machine pistol as a self-defence side arm for artillery crews, tank crews, and helicopter pilots.

Comparison with submachine gun

The dividing line between machine pistols and compact submachine guns is difficult to draw. Originally, "Maschinenpistole" was simply the German word for personal, automatic military weapons, while "submachine gun" was a term coined by John T. Thompson, American inventor of the Thompson submachine gun. While the term submachine gun usually refers to an automatic firearm larger than a pistol, several weapons are classed in both categories. The 1960s CZ-Scorpion, a Czechoslovak 7.65 mm weapon, for example, is often labeled a submachine gun. However, with its small magazine, it is small enough to be carried in a pistol holster, which suggests that it could be classified as a machine pistol.

In the 1980s, weapons such as the MAC-10 and the compact versions of the Uzi series have been placed in both classes. The popularity of submachine guns in recent years has led many weapons previously described as machine pistols to be advertised as submachine guns, such as the Brugger & Thomet MP9 (developed on the design of the Steyr TMP).

The Steyr TMP (Tactical Machine Pistol) is a 9 mm blowback-operated, rotating-barrel weapon that is 282 mm long and that can fire 800–900 rounds per minute; despite its small size, lack of a stock, and the fact that it is called a "tactical machine pistol", it is often classed as a compact submachine gun.[5] Likewise, the German Heckler & Koch MP5K (a weapon small enough to be concealed on one's person or in a briefcase) is also classed as a compact submachine gun.[6]

A machine pistol is typically based on a semi-automatic pistol design. While most machine pistols are designed to be fired with one hand, their light weight, small size, and extremely rapid rates of fire make them difficult to control. To improve accuracy, some machine pistols are fitted with a shoulder stock. Some, such as the Heckler & Koch VP70, will only fire single rounds unless the stock is attached, because there is a safety mechanism incorporated into the stock. The Beretta 93R offers an optional forward handgrip, which is another way of increasing weapon controllability in full automatic mode.

Tactics

There are many tactics where machine pistols come into play, including room clearing, personal defense, close quarter battle and door breaching.

Military

As an offensive weapon, the machine pistol has limited uses, because it fires pistol ammunition and has a short barrel, which means that it is both inaccurate and lacks power in open-country fighting at a several-hundred meter range. When the machine pistol was first introduced during the last year of World War I, it was used in trench warfare. In World War II, machine pistols were carried by platoon leaders, artillery crews, and tank crews.

In the decades after World War II, machine pistols were used in close quarter combat where a rifle would be too unwieldy, such as in urban house-to-house fighting or in tunnels. In these contexts, machine pistols were viewed as "room brooms", which could sweep a space with automatic fire. While training doctrines for machine pistols vary between armies, in general, soldiers are instructed to use the weapon for short bursts, rather than for an uninterrupted period of automatic fire, because the weapon easily gets out of control in sustained firing, which means that many of the rounds may be off target. As well, given the high rate of fire of machine pistols, sustained firing wastes ammunition and can easily deplete the magazine too quickly.

In the 1990s and 2000s, as body armor became increasingly common on battlefields, the machine pistol became less useful in a military setting, because its low-powered pistol ammunition is not able to penetrate ceramic-plated Kevlar military vests. As a result, armies began to issue a new weapon to artillery crews and tank crews: the personal defense weapon, a compact submachine gun-like firearm which incorporates some of the advantages of a carbine, in that it can fire armor-piercing, higher-powered ammunition. Unlike the machine pistol, which is a relative of the semi-automatic pistol, the PDW is more like a scaled-down rifle.

Military machine pistols usually use fully jacketed ammunition in accordance with the Hague convention. Fully jacketed cartridges are less likely to become deformed and flattened on impact, which means that permanent cavitation inflicted on human tissue, and therefore the damage that they do to the body, is moderated. Some special forces use specialty ammunition in machine pistols or PDWs, such as loading several tracer rounds per magazine to aid in night-time shooting, or for a squad leader to direct his soldiers' attention toward a location for concentrated fire.

Law enforcement

Government security service bodyguards for VIPs security are sometimes issued machine pistols rather than submachine guns for tactical and media considerations. Whereas a team of bodyguards carrying larger submachine guns may indicate to would-be aggressors that the VIP is an important politician, a machine pistol such as the Glock 18 can be concealed in a standard holster. Since even the unholstered weapon is indistinguishable to most observers from a standard pistol, this may lessen attention from media or potential attackers as to the security measures that are in place.

When bodyguards are carrying a machine pistol in a concealed holster, they have to choose a weapon that does not have parts that might snag when the weapon is being withdrawn from the holster. For similar reasons, a bodyguard with a holster-carried, concealed weapon is typically not able to mount accessories onto the weapon, such as optical sights or forward handgrips. The exception is cases in which a bodyguard conceals the weapon in a briefcase.

Law enforcement agencies use machine pistols for hostage rescues and for breaching gang compounds because the weapons offer a very high rate of fire in a small weapon, which can be maneuvered inside houses and stairwells, places where an assault carbine such as the Colt M4 would be unwieldy. Another reason that law enforcement agencies use machine pistols in hostage rescue situations is that the low-powered pistol ammunition loses its energy quickly, which means that the bullets are less likely to go through walls and injure innocent parties. Some Mexican police officers working in urban environments carry both a 9 mm machine pistol and a standard semi-automatic side arm.[7]

Air marshals who provide security on private airplanes also carry machine pistols and may use speciality ammunition such as frangible bullets, which break apart when upon impact. Frangible bullets such as the Glaser Safety Slug are designed to ricochet less and be less likely to puncture the hull of an aircraft, which lessens the danger of decompression if the officer has to fire on an attacker.

When law enforcement agencies are using machine pistols in non-concealed settings, this makes it feasible to add accessories such as optical sights, laser sights, flashlights, forward handgrips, rear stocks, or sound suppressors. Many 2000s-era machine pistols have mounting rails to facilitate the addition of accessories. Agencies sometimes use sound suppressors for maneuvers in which it is anticipated that shots may be fired indoors, because the sound pressure from indoor firing can be deafening. Some machine pistols offer the option of using translucent plastic magazines which allows the officer to quickly verify the level of ammunition left in the magazine. Another option that law enforcement officers may use on occasion is high-capacity magazines such as single or double drum magazines.

Different law enforcement agencies in different countries have different regulations regarding how machine pistols are loaded and carried. Depending on the type of machine pistol, some agencies train their officers to carry the weapon with a round in the chamber, the weapon cocked and the safety on. Other agencies may prefer that officers carry the weapon without a round in the chamber. While this makes the weapon safer to carry and reduces the likelihood of an accidental discharge, it also means that there will be a longer delay before the officer can fire the weapon.

Agencies also have different training doctrines regarding how the weapon is drawn and brought into position onto the target. Variants include withdrawing the weapon while pointing it downwards, then bringing it up towards the target; the same method but pointing the weapon upwards, and bringing it down towards the target; and the cross-body draw. The first method may be safer, in that if there are any unintended discharges, they will go into the ground. With a machine pistol that can empty its 20-round magazine in a second and a half, bringing the weapon into play by moving it down onto the target or using a cross body draw could result in unintended injuries if the weapon accidentally discharges.

Criminal use

MAC-10 and TEC-9

In the decades after the 1980s, there were newspaper reports about the use of the MAC-10 or the Tec-9 in crimes, including gang-related crimes and its use by Dylan Klebold in the Columbine High School massacre. The Tec-9 (known as the AB-10 after 1994), is sold as a semi-automatic weapon, not a machine pistol. However, early open-bolt models could be easily converted to fire fully automatically. Despite this, Klebold's pistol was, in fact, a post-ban AB-10. The majority of criminal uses of the MAC-10/11 and Tec-9 style firearms involve unconverted, semi-automatic versions. Failure to differentiate between the two has led to some confusion over what constitutes a true machine pistol, especially among the news media.

The fully automatic MAC-10 is technically a machine pistol. Though semi-automatic versions of the gun were sold without a stock and later converted, either legally or illegally, to full-auto, their classification would still be a submachine gun with the stock removed. Confusion is rampant due to the identical outward appearance of the firearms.

Other types

In September 1997,The Gazette from Montreal reported that the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) had arrested a Canadian gang operating a gun-running ring in Ontario and Quebec. The ring sold "high-calibre" machine guns, machine pistols, handguns, explosives (500 pounds of C-4 plastic explosive) and thousands of rounds of ammunition to biker gangs and other criminals.[9] The Canadian Department of Justice stated in 1998 that as the preferred weapons of drug dealers are illegal in Canada, they are obtained by smuggling.[9]

A Canadian undercover officer interviewed on the issue of guns and the illegal drug trade "... noted that the weaponry in the trade is definitely more powerful than in previous years", with an increasing number of criminals using machine pistols and submachine guns. He stated that within the drug trade firearms are used as status symbols, a means of protection and ... for executions ... [and] to intimidate potential informants and to enforce debt repayment".[9]

During the 1990s in Croatia, "illicit copies" of "machine pistols were manufactured locally", including the "‘ERO’, an exact copy of the Israeli UZI machine pistol". These illegally made Croatian weapons "also ended up in the Dutch criminal world: between 1998 and 2000, a couple dozen ‘Croatian UZIs’ were seized". In Croatia, "machine pistols of the American Ingram brand" were also illegally copied and manufactured.[10]

In Serbia on 3 August 2001 "assailants gunned down Momir Gavrilovic on the asphalt of a parking lot in New Belgrade" with a "7.65mm ‘scorpion’ machine pistol and [he] died on the spot." "The crime came to national attention only five days later". Gavrilovic was "a former member of Serbian State Security", who shortly before his death had "... provided documentary evidence of corruption, even naming names."[11]

Reception

Machine pistols have long been criticized for their inaccuracy. The inaccuracy of most machine pistols occurs because it is hard to control a fully automatic weapon that has such a low weight and in many cases, lacks a proper shoulder stock. As a result, in the hands of all but the most expert shooters, machine pistols being fired on full automatic tend to rise up during firing. Machine pistols also tend to have a very small sight radius and short barrels, meaning that the effectiveness beyond 50 meters degrades rapidly. One solution to improve controllability is the use of burst-limiters. Commonly, three or two-round bursts are used. Another solution is to steady the weapon in some fashion, either by outfitting it with a shoulder stock, using a shoulder strap to pull down on the front of the barrel, or resting the weapon against a hard surface which can be used as a bracing point. Slower rates of fire also allow better controllability. Use of a ported barrel, muzzle brake or suppressor can further be used to reduce muzzle climb.

Gunsite, a US firearms training facility, decided against teaching machine pistol firing when it was founded in 1976. Facility experts believed that it is "a slob's weapon, useful only by half-trained or poorly motivated troops"; they claimed that the machine pistol "hits no harder than a pistol and is no more portable than a rifle." Nevertheless, even the critics from Gunsite concede that the machine pistol is useful for a few situations, such as boarding an enemy boat in low light or when repelling boarders in a naval situation. Walt Rauch notes that "... despite the 50 to 70 years of bad press that has accrued to the concept of shooting a hand-held machine pistol", in which critics contend that the weapon will "spray bullets indiscriminately all over the area", he believes that the 2000s-era models such as the Glock 18 are controllable and accurate in full-auto shooting.[12] Leroy Thompson states that "...machine pistols were reasonably good for use from within a vehicle or for issue to VIP [bodyguard] drivers to give them a marginally more effective weapon during an evacuation under fire". Thompson states that when serving as security detail, "where we had Beretta 92s, we would try to grab at least one 93R 20-round mag to carry as a spare for breaking ambushes."[13]He states that machine pistols are "...[h]ard to control in full-auto fire", which means that there is nothing that a machine pistol "...can do that other weapons available today can't do more efficiently."[14]

See also

- Assault weapon

- Machine gun

- Personal defense weapon

- Semi-automatic pistol

- Service pistol - issued to military personnel

- Submachine gun

References

- ^ James Smyth Wallace. Chemical Analysis of Firearms, Ammunition, and Gunshot Residue. CRC Press. 2008. p. xxiii

- ^ "MAC-10/MAC-11 Machine Pistol". Cheaperthandirt.com. Retrieved 2009-11-05.

- ^ "Modern Firearms — IMI UZI / Mini UZI / Micro UZI submachine gun". World.guns.ru. Retrieved 2009-11-05.

- ^ SMALL ARMS REVIEW MAGAZINE VOL 9,No.12 SEPTEMBER 2006. PAGES 96 TO 99

- ^ Hogg, Ian V.; John Weeks (2000). Military small arms of the 20th century (7th ed.). Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications,. p. 99. ISBN 9780873418249.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Hogg, Ian V.; John Weeks (2000). Military small arms of the 20th century (7th ed.). Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications,. pp. 122–123. ISBN 9780873418249.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Jeffrey S. Slovak. Styles of Urban Policing: Organization, Environment, and Police Styles in Selected American Cities. NYU Press, 1988 ISBN 0814778755, ISBN 978-0-8147-7875-3 p. 1

- ^ "Modern Firearms — Intratec TEC-9 DC-9 AB-10 Interdynamic KG-99 pistol". World.guns.ru. Retrieved 2010-03-28.

- ^ a b c Oscapella, Eugene (July 1998). The Relationship Between Illegal Drugs And Firearms: A Literature Review (PDF) (Report). Department of Justice, Government of Canada. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

- ^ Toine Spapens. Trafficking in Illicit Firearms for Criminal Purposes within the European Union. European Journal of Crime, Criminal Law and Criminal Justice (2007) 359–381. Available online at: http://arno.uvt.nl/show.cgi?fid=68801 Accessed on March 28, 2010.

- ^ SERBIA’S TRANSITION: REFORMS UNDER SIEGE 21 September 2001. International Crisis Group. Available online at: http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/pdfid/3bd973a90.pdf Accessed on March 28, 2010

- ^ Rauch, Walt. "GLOCK 18". Remtek.com. Retrieved 2009-11-05.

- ^ Thompson, Leroy (October 2010). "The Machine Pistol - Why Does It Even Exist?". S.W.A.T. Magazine.

- ^ Thompson, Leroy (October 2010). "The Machine Pistol - Why Does It Even Exist?". S.W.A.T. Magazine.

Further reading

- Mullin, Timothy J. The Fighting Submachine Gun, Machine Pistol, and Shotgun. Boulder: Paladin Press, 1999.

- Gotz, Hans Dieter. German Military Rifles and Machine Pistols, 1871-1945, Schiffer Publishing, Ltd. West Chester, Pennsylvania, 1990.

- Henrotin, Gerard Full-auto Conversion for Browning Pistols, HLebooks.com (downloadable ebook), 2003.