Deep-submergence vehicle

A deep-submergence vehicle (DSV) is a deep-diving manned submarine that is self-propelled. Several navies operate vehicles that can be accurately described as DSVs. DSVs are commonly divided into two types: research DSVs, which are used for exploration and surveying, and DSRVs (Deep Submergence Rescue Vehicle), which can be used for rescuing the crew of a sunken navy submarine, clandestine (espionage) missions (primarily installing wiretaps on undersea cables), or both. DSRVs are equipped with docking chambers to allow personnel ingress and egress via a manhole.

The real-life feasibility of any DSRV-based rescue attempt is hotly debated, because the few available docking chambers of a stricken submarine may be flooded, trapping the sailors still alive in other dry compartments. The only attempt to rescue a stricken submarine with these so far (the Russian submarine Kursk) ended in failure as the entire crew who survived the explosion had either suffocated or burned to death before the rescuers could get there. Because of these difficulties, the use of integrated crew escape capsules, detachable conning towers, or both have gained favour in military submarine design during the last two decades. DSRVs that remain in use are primarily relegated to clandestine missions and undersea military equipment maintenance. The rapid development of safe, cost-saving ROV technology has also rendered some DSVs obsolete.

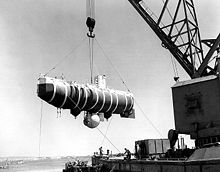

Strictly speaking, bathyscaphes are not submarines because they have minimal mobility and are built like a balloon, using a habitable spherical pressure vessel hung under a liquid hydrocarbon filled float drum. In a DSV/DSRV, the passenger compartment and the ballast tank functionality is incorporated into a single structure to afford more habitable space (up to 24 people in the case of a DSRV).

Most DSV/DSRV vehicles are powered by traditional electric battery propulsion and have very limited endurance. Plans have been made to equip DSVs with LOX Stirling engines but none have been realized so far due to cost and maintenance considerations. All DSVs are dependent upon a surface support ship or a mother submarine, that can piggyback or tow them (in case of the NR-1) to the scene of operations. Some DSRV vessels are air transportable in very large military cargo planes to speed up deployment in case of emergency rescue missions.

List of deep submergence vehicles

Trieste class bathyscaphe

- FNRS-2 – the predecessor to Trieste

- FNRS-3 – contemporary of Trieste I

- DSV-0 Trieste – the X-1 Trieste bathyscaphe has reached Challenger Deep, the world's deepest seabed. It was retired in 1966.[1]

- DSV-1 X-2 Trieste II – an updated bathyscaphe design, participated in clandestine missions, it was retired in 1984.[2][3]

Alvin class submarine

Alvin, owned by the Office of Naval Research (ONR) is operated under agreement by the National Deep Submergence Facility at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), where it conducts science oriented missions funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and ONR. Alvin has a maximum depth capability of 4,500 metres (2.8 mi) and operates from R/V Atlantis, an AGOR-23 class vessel owned by the ONR and operated by WHOI under a charter party agreement. The NSF has committed to the construction of a replacement sub with enhanced capabilities and 6,500-metre (4.0 mi) depth capability to replace Alvin, which will be retired upon its completion.

- DSV-2 Alvin – a deep diving sub, has a 4,500-metre (2.8 mi) depth capability, WHOI.[4]

- DSV-3 Turtle – Alvin's identical sibling, retired 1998, USN.[5]

- DSV-4 Sea Cliff – another Alvin class DSV sub, retired 1998, returned to active service on September 30, 2002, Sea Cliff has 6,000-metre (3.7 mi) depth capability, USN.[6]

- DSV-5 Nemo – another Alvin class DSV sub, retired 1998, USN.[7]

Nerwin class DSVN

- NR-1 Nerwin – , a decommissioned US Navy nuclear powered research and clandestine DSV submarine, which could roll on the seabed using large balloon wheels.[8]

Aluminaut

- Aluminaut – a DSV made completely of aluminum by the Reynolds Metals Aluminum Company, for the US Navy, once held the submarine deep diving record.[9] It is no longer operational.

Deepsea Challenger

- Deepsea Challenger – a DSV made by the Acheron Project Pty Ltd, has reached Challenger Deep, the world's deepest seabed.

Limiting Factor

- DSV Limiting Factor - a submersible commissioned to be built by Caladan Oceanic and designed and built by Triton Submarines of Sebastian, Florida. On December 19th, 2018 it was the first manned submersible to reach the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean, or 8,376 meters in the Brownson Deep, thus making it the deepest diving, currently operational submersible.[10] As of early 2019, the submersible was continuing its "Five Deeps Expedition" mission onboard its support ship, the DSSV Pressure Drop, to visit the bottom of all five of the world's oceans by the end of the year.

Priz

- Priz – a DSRV class of five ships built by the USSR and Russia. The titanium-hulled Priz class are capable of diving to 1,000 metres (0.62 mi). These mini-submarines can ferry up to 20 people for very brief periods of time (in case of a rescue mission) or operate submerged for two to three days with a regular crew of three to four specialists. In early 2005, the Russian AS-28 Priz vessel was trapped undersea and subsequently freed by a British ROV in a successful international rescue effort.

Mir

- Mir – a strictly civilian (research) class of two DSVs which were manufactured in Finland for the USSR. These bathyscaphe-derived vessels can carry three people down to depths of 6,000 metres (3.7 mi). After visiting and filming the RMS Titanic's wreck, two Mir submersibles and their support ship were loaned to a US Pacific trench surveying mission in the late 1990s and made important discoveries concerning sulphuric based life in "black smokers".

Kalitka-class DSVN

- AS-12 – a Russian counterpart to the American NR-1 clandestine nuclear DSV, is a relatively large, deep-diving nuclear submarine of 2,000 tons submerged displacement that is intended for oceanographic research and clandestine missions. It has a titanium pressure hull consisting of several conjoined spheres and able to withstand tremendous pressure — during the 2012 research mission it routinely dove to 2,500 to 3,000 metres (1.6 to 1.9 mi),[11][12] with maximum depth being said to be approximately 6,000 metres (3.7 mi). Despite the three-month mission time allowed by its nuclear reactor and ample food stores it usually operates in conjunction with a specialized tender, a refurbished Delta III-class submarine BS-136 Orenburg, which has its missile shafts removed and fitted with a special docking cradle on its bottom.

Konsul

- Konsul – a new class of Russian military DSVs, currently undergoing final acceptance trials before the official commissioning into the Navy.[13] They are somewhat smaller than the Mirs, accommodating a crew of two instead of three, but are purely domestically produced vessels and have a higher maximum depth due to their titanium pressure hulls: during the tests the original Konsul dove to 6,270 metres (3.90 mi).[14]

Nautile

- Nautile – a DSV owned by Ifremer, the French Research Institute for Exploitation of the Sea. The titanium-hulled Nautile is capable of diving to 6,000 metres (3.7 mi).

Shinkai

- DSV Shinkai – JAMSTEC (Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology) operates a DSV-series called Shinkai ("Deep Sea"). The latest DSV is Shinkai 6500 which can submerge to 6,500 metres (4.0 mi) with three crew members. JAMSTEC was operating a ROV called Kaikō, which was able to submerge to 11,000 metres (6.8 mi), but was lost at sea in May 2003.[15]

Pisces class DSV

Pisces class DSVs are three person research submersibles built by International Hydrodynamics of Vancouver in British Columbia with a maximum operating depth of 2,000 metres (1.2 mi) capable of dive durations of 7 to 10 hours. A total of 10 were built and are representative of late 1960s deep-ocean submersible design. Two (Pisces IV and V) are currently operated by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the first production vehicle is on display in Vancouver. Pisces VI is undergoing retrofit.

Sea Pole class bathyscaphe

Bathyscaphe series designed by the People's Republic of China, and there are three derivatives known to exist by 2010:

- Sea Pole class bathyscaphe: 2 built

- Jiaolong class bathyscaphe (Jiaolong): Developed from Sea Pole class, 1 built.

- Harmony class bathyscaphe: Developed from Jiaolong class, 1 built.

Shenhai Yongshi DSV

Shenhai YongshiDSV built in China and can dive to 4500m.

Ictineu 3

- Ictineu 3 – a three-men manned DSV. The hull is made of inox steel and it has a large 1,200-millimetre-diameter (47 in) semi-spheric acrylic glass viewport. It is designed to reach depths of 1,200 metres (3,900 ft), thus being the ninth-deepest submersible, and it is capable of diving during 10 hours using li-ion batteries.[16]

other DSV bathyscaphes

- Bathyscaphe Archimède – French-made bathyscaphe, operated around the time of the Trieste.

- FNRS-4

Deepest explorers

DSV Limiting Factor – 11,000 m[17]

DSV Limiting Factor – 11,000 m[17] Bathyscaphe Trieste – 11,000 m[18]

Bathyscaphe Trieste – 11,000 m[18] Deepsea Challenger – 11,000 m[19]

Deepsea Challenger – 11,000 m[19] Archimède – 9,500 m

Archimède – 9,500 m Jiaolong – 7,500 m

Jiaolong – 7,500 m DSV Shinkai 6500 – 6,500 m

DSV Shinkai 6500 – 6,500 m Konsul – 6,500 m

Konsul – 6,500 m DSV Sea Cliff – 6,000m[20]

DSV Sea Cliff – 6,000m[20] MIR – 6,000 m

MIR – 6,000 m Nautile – 6,000 m

Nautile – 6,000 m

- Figures rounded to nearest 500 metres

References

- ^ "Trieste". History.navy.mil. Archived from the original on 2010-03-17. Retrieved 2012-03-27.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Trieste II". History.navy.mil. Archived from the original on 2004-03-08. Retrieved 2012-03-27.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "No Name (DSV 1)". Nvr.navy.mil. 2009-09-14. Retrieved 2012-03-27.

- ^ "No Name (DSV 2)". Nvr.navy.mil. 1990-10-25. Retrieved 2012-03-27.

- ^ "No Name (DSV 3)". Nvr.navy.mil. Retrieved 2012-03-27.

- ^ "No Name (DSV 4)". Nvr.navy.mil. Retrieved 2012-03-27.

- ^ "No Name (DSV 5)". Nvr.navy.mil. Retrieved 2012-03-27.

- ^ "NR 1 Deep Submergence Craft". Archived from the original on October 18, 2004.

- ^ "Reynolds Aluminaut". Archived from the original on October 12, 2004.

- ^ Dean 2018-12-21T17:15:00-05:00, Josh. "An inside look at the first solo trip to the deepest point of the Atlantic". Popular Science. Retrieved 2018-12-29.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Ледовый поход Лошарика" [The Losharik Ice Tour] (in Russian). 29 October 2012.

- ^ Alexei Mikhailov; Vladimir Boloshin (29 October 2012). "Военный атомный батискаф «Лошарик» испытали в Арктике" [Military atomic bathyscaphe "Losharik" tested in the Arctic]. Izvestia (in Russian).

- ^ ""Консул" испытан – ВПК.name" ["Consul" is tested] (in Russian). Vpk.name. 22 June 2011. Retrieved 2012-03-27.

- ^ "Submersible Consul tested: Voice of Russia". :. 2011-07-07. Retrieved 2012-03-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "Robot sub reaches deepest ocean". BBC News, 3 June 2009.

- ^ Soro, Selena (11 May 2015). "LIctineu 3' lluita per sobreviure" [The Ictineu 3 fight to survive] (in Catalan). Ara. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ "Deepest Ever Submarine Dive Made by Five Deeps Expedition". The Maritime Executive. 2019-05-14. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ "DEEPSEA CHALLENGER Versus Trieste". 17 February 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (7 December 2011). "Oceans' deepest depth re-measured".

- ^ "Vessel Returns to Point Loma : Navy Vehicle Takes a Plunge to a Record Depth". Los Angeles Times. 1985-03-30. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2019-06-27.

External links

- "Deep Submergence Vehicle (S-P)". Naval Vessel Register.

- "Deep Submergence Rescue Vehicle (S-P)". Naval Vessel Register.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20041017224027/http://www.chinfo.navy.mil/navpalib/factfile/ships/ship-dsrv.html

- "Research Vessels and Vehicles". Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology.

- "Robot sub reaches deepest ocean". BBC News, 3 June 2009.