Toonstruck

| Toonstruck | |

|---|---|

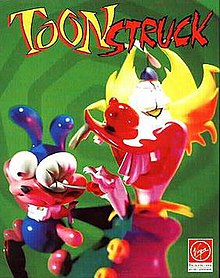

Toonstruck European cover | |

| Developer(s) | Burst Studios |

| Publisher(s) | Virgin Interactive Entertainment |

| Producer(s) | Ron Allen Dana Hanna |

| Designer(s) | Richard Hare |

| Programmer(s) | Douglas Hare Gary Priest |

| Artist(s) | William D. Skirvin |

| Writer(s) | Mark Drop Richard Hare Jennifer McWilliams |

| Composer(s) | Keith Arem |

| Platform(s) | MS-DOS |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Toonstruck is an adventure game developed by Burst Studios, published by Virgin Interactive Entertainment and released in 1996 for DOS. In the game, a live-action protagonist Drew Blanc, played and voiced by Christopher Lloyd, is transported into the cartoon world he created while suffering from a creative block. Blanc is accompanied by his animated sidekick Flux Wildly, voiced by Dan Castellanata.[1]

Conceived in 1993 as a game geared towards children, Toonstruck was later re-written to be more adult-oriented. Virgin Interactive invested huge amounts of money into the game, which ended up costing in excess of US$8 million. In addition to Lloyd and Castellanata, the cast includes several well-known actors and voice actors such as Tim Curry, David Ogden Stiers and Jim Cummings. Toonstruck features scan-line compressed FMV that is composited with hand-drawn animated sequences produced by Burst, Nelvana and Rainbow Animation.

Toonstruck was well-received by gaming critics, who mostly praised the quality of the animation, puzzles and performances by Lloyd and Castellanata, although it was a financial disappointment for Virgin. It has since been recognized as one of the best adventure games of all time, and has recently been re-released for modern computers by GOG.com and Steam.

Gameplay

Toonstruck is a point-and-click adventure game where the player controls Christopher Lloyd's digitized likeness, accompanied by his cartoon sidekick Flux. The game uses a "Bottomless Bag" as an inventory icon, and the mouse pointer, represented by an animated white-gloved hand, is context-sensitive, changing its icon depending on what it is rolled over.[2] Dialogue options with characters throughout the game are displayed as graphical icons that represent the topic of conversation. One of the standard icons is a cube of ice (for "breaking the ice" with a character); as dialogue options are exhausted, the cube melts into a puddle of water.[3]

The main objective of the game is to locate and collect several items that have opposite effects to those in a machine created by the main antagonist, Count Nefarious. Many of the puzzles in the game are based on object manipulation, although there are also some logic and arcade-style puzzles. For certain parts of the game, the player must use the abilities of Flux as a cartoon character to advance in the game.[3] Much like the LucasArts adventure games, it is not possible to die in the game, and there are no dead-ends that require the player to start over or load an earlier save file.[4]

Plot

Drew Blanc (Lloyd) is a cartoon animator and the original creator of the Fluffy Fluffy Bun Bun Show. The show has been an unprecedented ten year success for his company, but in reality, the many cute talking rabbits that star in the show sicken him. His self-revered creation, Flux Wildly, a wise-talking and sarcastic small purple character, has been denied the chance of starring in his own show. Drew's boss, Sam Schmaltz (Ben Stein), sets him the task of designing more bunnies to co-star in the Fluffy Fluffy Bun Bun Show by the next morning. However, the depressed animator soon nods off, suffering from acute artist's block.

Drew wakes early the next morning to inexplicably find his television switched on, announcing the Fluffy Fluffy Bun Bun Show. Suddenly, Drew is mysteriously drawn into the television screen and transported to Cutopia, an idyllic two-dimensional cartoon world populated by his own creations, among many other cartoon characters.

He soon befriends Flux Wildly (Dan Castellaneta), and discovers that this fictional paradise is being ravaged by a ruthless new character named Count Nefarious (Tim Curry) with a devastating weapon of evil, a flying machine equipped with a ray beam that mutates the pleasant, childish landscape and its inhabitants into dark and twisted counterpart versions of themselves. Upon meeting with Cutopia's King Hugh (David Ogden Stiers), Drew is given the task of hunting down and stopping Nefarious, thereby restoring peace and harmony to the land, in return for safe passage back to three-dimensional reality.

In the end, Drew manages to defeat Nefarious and returns to the real world, thinking his adventure was just a dream. He presents his new idea to Sam, The Flux & Fluffy Show, only for it to get shot down. As Drew resigns himself to his soulless job, Flux calls him through a communicator he gave him and tells him that the toon world is still in danger and Drew happily teleports away.

Development

Toonstruck was published by Virgin Interactive Entertainment and developed by Virgin's internal development studio Burst, based in Irvine, California and headlined by Chris Yates, a veteran of Westwood Studios, and Neil Young, who worked at Probe.[5] After David Perry and his associates left Virgin in 1993, the company struggled with internal development and hired Yates and Young to lead this division. In an interview by Edge, Yates stated that all senior producers at Burst had between "eight and ten years of experience", and that the studio was focused on having quality tools and technology to develop products with high production values.[5]

Development of the game began in October 1993, and finished in November 1996.[6] Virgin Interactive invested much money in the project,[7] and aimed at impressing audiences with high production values. "So much of the game was handled like a full-scale movie production", said artist John Pimpiano,[8] who was originally tasked with doing background art for the game, but became involved with other realms of production such as character development, storyboarding, color styling and marketing promos, among others.[7] The studio was inspired to take CD-ROM technology "even further" after the success of Virgin's The 7th Guest, and to make the game "as cinematic as possible".[7] Overall, 230 people worked in the game.[4] In 1994 Burst switched its early engine to that of The Legend of Kyrandia: Malcolm's Revenge, offered to them by Westwood. Since the programmers had to re-code much of the game, only about 5% of the original source code remained in the final game.[9]

By the end of development, Toonstruck had a high budget of over $8 million dollars ($13 million in 2020 figures). According to Next Generation, Virgin Interactive always acknowledged that Toonstruck would be expensive.[6] A Virgin Interactive insider suggested that the animation was of an unnecessarily high level of sophistication, exceeding the quality "of even Disney animated movies". Furthermore, the development team spent 18 months debugging the code written for the Kyrandia engine, further delaying the release and adding to the already high production budget.[6]

Writing

Toonstruck was meant to be a funny story about defeating some really weird bag guys, as it was when released, but originally it was also about defeating one's own creative demons.

—Co-writer and designer Jennifer McWilliams on the story of Toonstruck[10]

Toonstruck was originally conceived as "an interactive Who Framed Roger Rabbit? but in reverse," since a live-action character enters a fully-animated cartoon world.[6] Executive producer David Bishop conceptualized the game as a children's game "where a villain was draining the colour out of the world, turning it black and white". However, once Bishop's concept was passed on to co-writer and designer Jennifer McWilliams, it went through several revisions to make it more adult-oriented, with comic violence and touches of parody and cynicism.[11] McWilliams wrote the second part of the game to be more psychological, with Drew facing his fears, living out his fantasies and eventually restoring his creativity.[10] The final screenplay was credited to McWilliams, Richard Hare and Mark Drop.[12]

The character of Flux Wildly was created after that of the protagonist Drew Blanc, as a companion and "fun-loving" sidekick, because he gave a window "into the 'real' Drew". To McWilliams, Flux was also "a great addition" for the puzzles and humor.[10] Developers aimed at creating a world that felt as though it was "living" and that evolved as the story events progressed. To accomplish that in writing, the NPC dialogue was programmed to change as critical events happened in the game so that characters commented on these events instead of just repeating dialogue from earlier.[10]

With the delays to the game's production and the release date getting closer, Virgin executives decided to split the game's content in two and expected to have the unreleased half be included in a potential sequel. Due to Virgin's decision to divide the game in two, the writers had to come up with an ending that properly concluded the game "halfway through, with a cliffhanger that would, ideally, introduce part two." Since the entire story arc was carefully though-out, McWilliams felt Virgin's decision "definitely disrupted that", but nonetheless believed the studio did well under the circumstances.[10]

Design and animation

Creative influences for Toonstruck's characters, locations and animations were the classic cartoons of Warner Bros., Tex Avery, Hanna-Barbera and Walt Disney Studios. Elements of the game were also inspired by British humor and the "lampooning" of American pop culture.[7] Canadian animation studio Nelvana signed a deal with Virgin Interactive to produce animation for Toonstruck through Nelvana's commercials production arm Bear Spots Inc. It was Nelvana's first contract with Virgin.[13] There were also animation cels and characters that were developed and keyframed by Burst and finished by Rainbow Animation, in the Philippines.[8][14] Burst's animators did much of their work traditionally, sketching characters and their movements on paper and then animating these frames. The company used computer technology from Silicon Graphics, as well as software such as Deluxe Paint and Autodesk Animator, which were used for coloring and finishing of the animated sequences. Over 11.000 animations were made by Burst during development. [4]

The full-motion footage of the game's live-action actors was shot in Burst's own motion capture studio, with hundreds of hours of performance against a green screen. In order to make post-production more efficient and easier, Burst first filmed empty scenes and then introduced the actor. A program by Silicon Graphics was used to calculate the difference in lighting and color between the two types of footage, thereby speeding up the process of color correction.[15] The footage was then composited and edited together with the animation by Burst's in-house animators.[16] Richard Hare served as director of the live-action production.[17]

McWilliams noted the team designed many ideas they felt were funny and interesting, without focusing on what was achievable within the budget and schedule. For the most part, the company gave the team creative freedom, but intervened when more content was made than could be included in one game and decided to cut half the material from the final game. This forced Burst to rework the game under this restriction.[10]

Casting and voice work

According to Jennifer McWilliams, most of the writing for the game was completed before the actors were cast, but the characters ultimately voiced by Tim Curry were written with him in mind. Burst had initially cast a different actor to voice Flux Wildly, but replaced him with Dan Castellanata, known for voicing Homer Simpson, after the studio decided the first choice would not be a good fit.[8] Christopher Lloyd, then-known for his roles in the Back to the Future series and Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, was cast in the live-action role of cartoonist Drew Blanc. Ben Stein played the role of Blanc's boss, also live-action.

Curry voiced the antagonist Count Nefarious. David Ogden Stiers, known for his work in M*A*S*H and Beauty and the Beast, voiced King Hugh, the king of Cutopia. Additional vocal performances were given by All Dogs go to Heaven voice actor Dom DeLuise, as well as Jeff Bennett, Corey Burton, Jim Cummings, Tress MacNeille, Rob Paulsen, April Winchell and Frank Welker.[12]

Sound design

Keith Arem was Toonstruck's animation music and sound designer.[17] While Arem composed original music for the game, he also employed a mixed of public domain classical music, such as Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy by Tchaikovsky, and production music supplied by APM, such as "Happy Go Lively" by Laurie Johnson.[18] Standard sound effects from classic cartoons were also included in the sound design for Toonstruck.[19][3]

Release

In December 1996 Virgin Interactive teamed up with Happy Puppy to launch the official website for Toonstruck, with email communication between Virgin and consumers and the ability to enter a contest to win CD-ROMs and merchandise.[20]

Toonstruck was originally planned to launch Q4 1995, but was pushed to a 1996 release date in October 1995.[21] By December 1995 the game was expected to launch Q1 1996,[22] but was postponed again to the fall season.[23] Toonstruck was showcased at the 1996 edition of E3.[24] After several delays and six months after being previewed at E3, Toonstruck became ready for release in October 1996,[25] and launched in the U.S. for an initial price of $59.95.[26] The postponement of Toonstruck from late 1995 to October 1996 contributed to Virgin Interactive's reported loss of $14.3 million in the U.S. in 1995.[27]

Despite being well-received upon release, Toonstruck underperformed in sales and was a commercial failure;[28] this was partly attributed to a fading interest in point-and-click adventure games among consumers.[6] VP of marketing for Virgin Simon Jeffery admitted that the company "would have liked to have seen higher sales for Toonstruck", which by December 1996 had sold over 150,000 units worldwide. Executive producer Bishop lamented the lack of an effective marketing campaign for the game, and also criticized the packaging it came on. "As soon as you have the word 'cartoon' associated with a game, it aims at a young audience. But this was a game for adults with a lot of adult content," Bishop stated.[6] Destructoid also characterized the marketing as a factor in the game's financial failure, as well as Virgin's decision to cut the game in half.[29]

Nearly twenty years after being first published, Toonstruck was re-released for modern Windows systems by GOG.com on February 10, 2015,[30] and by Steam on November 15, 2016.[31] Both versions use the ScummVM emulator to run.[18]

Reception

| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| GameRankings | 75.14%[32] |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| Computer Gaming World | |

| GameSpot | 8.8/10[33] |

| Next Generation | |

| PC Gamer (US) | 70%[34] |

| Computer Games Strategy Plus | |

| PC Games | A-[37] |

| Entertainment Weekly | A-[38] |

| Computer and Video Games | 4/5[39] |

Toonstruck received mostly positive reviews. Brett Atwood of Billboard wrote that despite the game being "far from unique," it is "filled with plenty of challenging puzzles and cool cartoons".[40] Entertainment Weekly's Gary Eng Walk rated the game an A-, praising the level of difficulty and puzzles while noting that the controls "are sometimes clunky".[38] Computer and Video Games gave Toonstruck a 4 out of 5, calling it "the best point-and-click adventure for a long time". In its review, CVG compared the game favorably to LucasArts adventures games such as Day of the Tentacle and Monkey Island, and praised the "professional" cutscenes, controls and difficulty curve.[39] Petra Schlunk of Computer Gaming World gave the game a 5 out of 5, praising the story, characters, voice work and puzzles.[3]

Ron Dulin of GameSpot said Toonstruck was "overly-hyped for both its technical prowess and ingenious premise. ... the animation, while admirable, isn't mind-blowing, and the story is mildly amusing at best. But what's great about Toonstruck is that neither of these drawbacks matters in the slightest; the designers have made a great game by creating an experience that is entertaining and challenging but doesn't become too frustrating or too easy." He elaborated that the game is consistently clear about what the player needs to do, and the puzzles deal solely with how to go about doing it.[33] Major Mike of GamePro found the dialogue tedious and unfunny, but praised every other aspect of the game, particularly the puzzle interface, whimsical music, and integration of live action video with fluid cartoon animation. He summarized, "although it lags at times, it contains an excellent blend of puzzle-solving and cartoon animation."[41] CGW's Schlunk singled out the voice acting as "brilliant".[3] Edge described Toonstruck as "the closest any post-Monkey Island effort, with the possible exception of Broken Sword, has come to getting the ingredients right," and gave the game an 8 out of 10. The magazine praised the game's puzzles and highlighted the non-linear aspect of the game. The review did criticize the integration of digitized live-action footage with the animated scenes, and stated the humor was excessively over-the-top at parts of the game.[42]

Aaron Ramshaw of Adventure Gamers wrote that Toonstruck "remains one of the best adventures ever made" twenty-two years after it first came out. Ramshaw described the characters as "superbly crafted and portrayed" and Lloyd's comic timing as "particularly praiseworthy". Ramshaw also praised the quality of the animated cinematics, the non-linear puzzle design and musical score.[18] Adventure Classic Gaming's Cyrus Zatrimailov gave the game a 4 out of 5 score; he praised the graphics but had mixed thoughts on the puzzles, believing some of them to be "totally absurd" and "plain weird".[43]

Some reviews were less positive. Next Generation focused on the script, and assessed that "the dialog, slapstick humor, and relentless 'comedy' situations are tired and mostly ripped off from past and present cartoon creations. You've seen most of these jokes before, and done better 40 years ago."[36] Dave Nuttycombe of The Washington Post praised Lloyd's performance, but wrote that after it "wears off, you're left with conventional art and a public-domain soundtrack", and described the game as "tedious".[44] Hardcore Gaming 101 writer Kurt Kalata gave a mixed review of the game, with praise towards the "varied yet unique" art style, the audio and voice acting. However, Kalata criticized the writing as not "terribly good" and the dialogue as "rarely any funny", and wrote the game feels incomplete.[19]

Legacy

Toonstruck was named the 37th best computer game ever by PC Gamer UK in 1997.[45] The game was a finalist for Computer Gaming World's 1996 "Adventure Game of the Year" award,[46] which ultimately went to The Pandora Directive.[47] In 2011, Adventure Gamers named Toonstruck the 93rd-best adventure game ever released.[28] TechRadar's Jordan Oloman included the game in his list of the 7 best adventure games on PC.[48]

Cancelled sequel

After the game's financial failure, Virgin cancelled plans to make a sequel to Toonstruck, which would have used content cut from the first installment. Sound designer for the game Keith Arem, who owns the rights to Toonstruck, has expressed interest in re-releasing the game as a full version, which would include the second half of the game. However, after stating he would need "tremendous" fan support to justify a Toonstruck re-release, a petition calling for the sequel was created in 2010 by fans.[49][50][51] Prior to this, an Internet forum of dedicated fans of the game had previously attempted to piece together the unreleased content into a playable fan-made game.[49] The increased interest in a Toonstruck 2 has also led to the creation of a creepypasta story centering around the unreleased sequel.[52]

In May 2011, Keith Arem confirmed he and his team were currently working on an enhanced re-release of ToonStruck, to which they may add some of the sequel's content if they can afford it. He has also stated they'd like to re-build the fanbase first, before moving onto the development of Toonstruck 2.[53] It was confirmed by Arem that an official announcement for the enhanced edition would hopefully be made by the time of Comic Con in July 2011.[53]

In June 2011, Trevor Greer, a friend of Arem's, confirmed on the Toonstruck 2 Facebook page that his father, Arem and himself are overseeing the project through Arem's owned PCB Productions company. Greer also answered some fan questions, most notably mentioning that an iOS version of the game is in development first for iPhone/iPad. A PC & Mac release may happen soon after depending on its success. More info was to be announced at Comic Con in July. However, a rep at the PCB productions booth said they had planned to make an announcement during the convention, but were waiting for the right word to say so due to legal issues being resolved at the moment.[53]

In 2014, Arem gave the fanbase a handful of updates through the Toonstruck Two Petition Facebook group and Twitter. In February, he wrote that they would "need to raise significant capital and fan interest to bring this game back to life" and "we need to show investors and distributors that we can sell hundreds of thousands of games," tasking the community to recruit as many fans and followers in social media as possible.[54] In June, Arem posted for the community that "very good news is on the way" and that there would be a large update in "the next few weeks."[55] When asked on Twitter, Arem said that they hoped to have an announcement by Comic Con in the end of July.[56] However, the announcement was once again postponed due to the copyright issues still being unresolved.

See also

References

Citations

- ^ "Toonstruck". GamePro. No. 92. IDG. May 1996. p. 48.

- ^ Morgan 1996, p. 44.

- ^ a b c d e f Schlunk, Petra (June 1, 1997). "Toonstruck". Computer Gaming World. Archived from the original on August 16, 2000.

- ^ a b c Morgan 1996, p. 45.

- ^ a b "Profile: Neil Young and Chris Yates". Edge (40). Future plc: 21. December 1996. ISSN 1350-1593.

- ^ a b c d e f "What the hell happened?: Toonstruck (NG Special)". Next Generation (40): 43. April 1998.

- ^ a b c d Walker-Emig 2017, p. 65.

- ^ a b c Walker-Emig 2017, p. 66.

- ^ Morgan 1996, p. 43.

- ^ a b c d e f Walker-Emig 2017, p. 67.

- ^ Walker-Emig 2017, p. 64.

- ^ a b Greenman 1996, p. 35.

- ^ Harvey Enchin; Brendan Kelly (April 22, 1996). "Ad prod'n subsid playing games". Variety.

- ^ Greenman 1996, p. 37.

- ^ Morgan 1996, p. 46.

- ^ Rubenstein, Glenn (February 10, 1996). "Toonstruck! is an adventure in humor". San Francisco Examiner. San Francisco, California. p. B1.

- ^ a b Greenman 1996, p. 36.

- ^ a b c Ramshaw, Aaron (December 28, 2018). "Toonstruck". Adventure Gamers. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ a b Kalata, Kurt (September 15, 2017). "Toonstruck". Hardcore Gaming 101.

- ^ "CD-ROM developers and publishers expanding interactive marketing potential of Internet". Business Wire. December 12, 1996.

- ^ "NOT SO SOON, TOON". Computer Retail Week. 5 (114): 25. October 9, 1995. ISSN 1066-7598.

- ^ "Toonstruck". GamePro (UK). No. 4. IDG. December 1995. p. 86.

- ^ Sherman, Christopher (December 1995). "Movers & Shakers". Next Generation (12). Imagine Media: 22.

- ^ "LIGHTS! SOUNDS! ACTION!; LOS ANGELES CONVENTION CENTER SHOWCASES NEWEST VIDEO GAMES, COMPUTER COMPACT; DISCS". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. May 18, 1996.

- ^ "Toonstruck aimed at the older game market". The Sunday Star-Times. Auckland. November 10, 1996.

- ^ Walk, Gary Eng; Forer, Bruce (December 6, 1996). "The week". Entertainment Weekly (356). ISSN 1049-0434.

- ^ "Virgin announces $14m loss". Multimedia Business Analyst. Informa plc. March 13, 1996.

- ^ a b AG Staff (December 30, 2011). "Top 100 All-Time Adventure Games". Adventure Gamers.

- ^ The Games That Time Forgot: Toonstruck Archived 2009-10-09 at the Wayback Machine destructoid.com

- ^ "Release: Toonstruck". GOG.com. February 10, 2015. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ "Toonstruck on Steam". Steam. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ Toonstruck for PC Archived 2009-10-08 at the Wayback Machine GameRankings

- ^ a b Toonstruck Review Archived 2015-09-19 at the Wayback Machine GameSpot

- ^ Whitta, Gary (January 1997). "Reviews; Toonstruck". PC Gamer US. 4 (1): 254, 255.

- ^ Bauman, Steve (1996). "Toonstruck". Computer Games Strategy Plus. Archived from the original on February 19, 2005.

- ^ a b "Toon Out". Next Generation. No. 26. Imagine Media. February 1997. p. 130.

- ^ Olafson, Peter. "Toonstruck". PC Games. Archived from the original on July 11, 1997.

- ^ a b Gary Eng Walk (December 6, 1996). "Videogame Review: 'Toonstruck'". Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ a b "Toonstruck Review". Computer and Video Games (181): 81. December 1996.

- ^ Atwood, Brett (December 21, 1996). "Enter*active". Billboard. 108 (51). ISSN 0006-2510.

- ^ "PC GamePro Review DOS: Toonstruck". GamePro. No. 100. IDG. January 1997. p. 64.

- ^ "Testscreen: Toonstruck". Edge (40). Future plc: 76–77. December 1996. ISSN 1350-1593.

- ^ Zatrimailov, Cyrus (November 24, 2008). "Toonstruck". Adventure Classic Gaming. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ Nuttycombe, Dave (January 17, 1997). "Screen Shots". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. p. 58.

- ^ Flynn, James; Owen, Steve; Pierce, Matthew; Davis, Jonathan; Longhurst, Richard (July 1997). "The PC Gamer Top 100". PC Gamer UK (45): 51–83.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Staff (April 1997). "Best of the Bunch; Finalists Named for CGW Premier Awards". Computer Gaming World (153): 28, 32.

- ^ Staff (May 1997). "The Computer Gaming World 1997 Premier Awards". Computer Gaming World (154): 68–70, 72, 74, 76, 78, 80.

- ^ Oloman, Jordan (October 10, 2018). "Best adventure games on PC". TechRadar. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ a b Walker, John (August 6, 2010). "Show Tremendous Interest In Toonstruck 2". Rock, Paper, Shotgun. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- ^ Toonstruck 2 petition group on Facebook

- ^ Toonstruck 2 petition Twitter account Archived 2016-03-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gates, Christopher (June 15, 2018). "Gaming bombs that somehow became cult classics". SVG.com. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- ^ a b c The Toonstruck Two Petition Facebook group

- ^ Feb 2014 Keith Arem remarks

- ^ June 2014 Keith Arem remarks

- ^ Keith Arem on Twitter Archived 2014-07-14 at the Wayback Machine

Bibliography

- Greenman, Robin (1996). Toonstruck Manual.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Walker-Emig, Paul (2017). "The Making of Toonstruck". Retro Gamer (174): 64–67. ISSN 1742-3155.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Morgan (July–August 1996). "Toonstruck". Joystick (in French) (73): 42–46. ISSN 1145-4806.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: date format (link)