Chronology of the universe: Difference between revisions

→Far future and ultimate fate: add rare events |

|||

| Line 353: | Line 353: | ||

There are several competing scenarios for the possible long-term evolution of the universe. Which of them will happen, if any, depends on the precise values of [[physical constant]]s such as the [[cosmological constant]], the possibility of [[proton decay]], and the natural laws [[beyond the Standard Model]]. |

There are several competing scenarios for the possible long-term evolution of the universe. Which of them will happen, if any, depends on the precise values of [[physical constant]]s such as the [[cosmological constant]], the possibility of [[proton decay]], and the natural laws [[beyond the Standard Model]]. |

||

In the very long term (after many more billion years of cosmic time), the [[Stelliferous Era]] will end, as stars cease to be born. If the expansion of the universe continues as expected, eventually all but the nearest galaxies will be carried away from us by the [[metric expansion of space|expansion of space]] at such a velocity that our [[observable universe]] will be limited to [[Laniakea Supercluster|our own]] gravitationally bound local [[galactic cluster]]. Beyond this, if the universe continues to expand and stays in its present form, all objects in the universe will cool and (with the [[proton decay|possible exception of protons]]) gradually decompose back to their constituent particles and then into subatomic particles, by a variety of possible processes. But this will take a duration of time that is almost inconceivable to most people, compared to which the entire 13.8 billion years of the universe would seem like an tiny instant in time. |

In the very long term (after many more billion years of cosmic time), the [[Stelliferous Era]] will end, as stars cease to be born. If the expansion of the universe continues as expected, eventually all but the nearest galaxies will be carried away from us by the [[metric expansion of space|expansion of space]] at such a velocity that our [[observable universe]] will be limited to [[Laniakea Supercluster|our own]] gravitationally bound local [[galactic cluster]]. Beyond this, if the universe continues to expand and stays in its present form, all objects in the universe will cool and (with the [[proton decay|possible exception of protons]]) gradually decompose back to their constituent particles and then into subatomic particles and very low level photons and other [[fundamental particle]]s, by a variety of possible processes. But this will take a duration of time that is almost inconceivable to most people, compared to which the entire 13.8 billion years of the universe would seem like an tiny instant in time. |

||

Ultimately, in the extreme future, the following scenarios have been proposed for the ultimate fate of the universe. |

Ultimately, in the extreme future, the following scenarios have been proposed for the ultimate fate of the universe. |

||

*[[Heat death of the universe|Heat Death]]: In the case of indefinitely continuing [[metric expansion of space]], the energy density in the universe will decrease until, after an estimated time of 10<sup>1000</sup> years, it reaches [[thermodynamic equilibrium]] and no more structure will be possible. This will happen only after an extremely long time because first, all matter will collapse into [[black hole]]s, which will then evaporate extremely slowly via [[Hawking radiation]]. The universe in this scenario will cease to be able to support life much earlier than this, after some 10<sup>14</sup> years or so, when [[star formation]] ceases.<ref name=dying>A dying universe: the long-term fate and evolution of astrophysical objects, Fred C. Adams and Gregory Laughlin, ''Reviews of Modern Physics'' '''69''', #2 (April 1997), pp. 337–372. {{bibcode|1997RvMP...69..337A}}. {{doi|10.1103/RevModPhys.69.337}}.</ref><sup>, §IID.</sup> In some [[grand unified theories]], [[proton decay]] after at least 10<sup>34</sup> years will convert the remaining interstellar gas and stellar remnants into leptons (such as positrons and electrons) and photons. Some positrons and electrons will then recombine into photons.<ref name=dying /><sup>, §IV, §VF.</sup> In this case, the universe has reached a high-[[entropy]] state consisting of a bath of particles and low-energy radiation. It is not known however whether it eventually achieves [[thermodynamic equilibrium]].<ref name=dying /><sup>, §VIB, VID.</sup> The hypothesis of a universal heat death stems from the 1850s ideas of [[William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin|William Thomson]] ([[Lord Kelvin]])<ref>Thomson, William. (1851). "On the Dynamical Theory of Heat, with numerical results deduced from Mr Joule's equivalent of a Thermal Unit, and M. Regnault's Observations on Steam." Excerpts. [§§1-14 & §§99-100], ''Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh'', March, 1851; and ''Philosophical Magazine'' IV. 1852, [from ''Mathematical and Physical Papers'', vol. i, art. XLVIII, pp. 174]</ref> who extrapolated the theory of heat views of mechanical energy loss in nature, as embodied in the first two laws of thermodynamics, to universal operation. |

:*[[Heat death of the universe|Heat Death]]: In the case of indefinitely continuing [[metric expansion of space]], the energy density in the universe will decrease until, after an estimated time of 10<sup>1000</sup> years, it reaches [[thermodynamic equilibrium]] and no more structure will be possible. This will happen only after an extremely long time because first, all matter will collapse into [[black hole]]s, which will then evaporate extremely slowly via [[Hawking radiation]]. The universe in this scenario will cease to be able to support life much earlier than this, after some 10<sup>14</sup> years or so, when [[star formation]] ceases.<ref name=dying>A dying universe: the long-term fate and evolution of astrophysical objects, Fred C. Adams and Gregory Laughlin, ''Reviews of Modern Physics'' '''69''', #2 (April 1997), pp. 337–372. {{bibcode|1997RvMP...69..337A}}. {{doi|10.1103/RevModPhys.69.337}}.</ref><sup>, §IID.</sup> In some [[grand unified theories]], [[proton decay]] after at least 10<sup>34</sup> years will convert the remaining interstellar gas and stellar remnants into leptons (such as positrons and electrons) and photons. Some positrons and electrons will then recombine into photons.<ref name=dying /><sup>, §IV, §VF.</sup> In this case, the universe has reached a high-[[entropy]] state consisting of a bath of particles and low-energy radiation. It is not known however whether it eventually achieves [[thermodynamic equilibrium]].<ref name=dying /><sup>, §VIB, VID.</sup> The hypothesis of a universal heat death stems from the 1850s ideas of [[William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin|William Thomson]] ([[Lord Kelvin]])<ref>Thomson, William. (1851). "On the Dynamical Theory of Heat, with numerical results deduced from Mr Joule's equivalent of a Thermal Unit, and M. Regnault's Observations on Steam." Excerpts. [§§1-14 & §§99-100], ''Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh'', March, 1851; and ''Philosophical Magazine'' IV. 1852, [from ''Mathematical and Physical Papers'', vol. i, art. XLVIII, pp. 174]</ref> who extrapolated the theory of heat views of mechanical energy loss in nature, as embodied in the first two laws of thermodynamics, to universal operation. |

||

*[[Big Rip]]: For sufficiently large values for the [[dark energy]] content of the universe, the expansion rate of the universe will continue to increase without limit. Gravitationally bound systems, such as clusters of galaxies, galaxies, and ultimately the Solar System will be torn apart. Eventually the expansion will be so rapid as to overcome the electromagnetic forces holding molecules and atoms together. Finally even atomic nuclei will be torn apart and the universe as we know it will end in an unusual kind of [[gravitational singularity]]. |

:*[[Big Rip]]: For sufficiently large values for the [[dark energy]] content of the universe, the expansion rate of the universe will continue to increase without limit. Gravitationally bound systems, such as clusters of galaxies, galaxies, and ultimately the Solar System will be torn apart. Eventually the expansion will be so rapid as to overcome the electromagnetic forces holding molecules and atoms together. Finally even atomic nuclei will be torn apart and the universe as we know it will end in an unusual kind of [[gravitational singularity]]. |

||

*[[Big Crunch]]: In the opposite of the "Big Rip" scenario, the [[metric expansion of space]] would at some point be reversed and the universe would contract towards a hot, dense state. This is a required element of [[oscillatory universe]] scenarios, such as the [[cyclic model]], although a Big Crunch does not necessarily imply an oscillatory universe. Current observations suggest that this model of the universe is unlikely to be correct, and the expansion will continue or even accelerate. |

:*[[Big Crunch]]: In the opposite of the "Big Rip" scenario, the [[metric expansion of space]] would at some point be reversed and the universe would contract towards a hot, dense state. This is a required element of [[oscillatory universe]] scenarios, such as the [[cyclic model]], although a Big Crunch does not necessarily imply an oscillatory universe. Current observations suggest that this model of the universe is unlikely to be correct, and the expansion will continue or even accelerate. |

||

*[[Vacuum instability]]: Cosmology traditionally has assumed a stable or at least [[metastability|metastable]] universe, but the possibility of a [[false vacuum]] in [[quantum field theory]] implies that the universe at any point in spacetime might spontaneously collapse into a lower energy state (see [[Bubble nucleation]]), a more stable or "true vacuum", which would then expand outward from that point with the speed of light.<ref name="turnerwilczek">{{cite journal |author=M.S. Turner |author2=F. Wilczek |title=Is our vacuum metastable? |journal=Nature |volume=298 |date=1982 |issue=5875 |pages=633–634 |doi=10.1038/298633a0 |bibcode=1982Natur.298..633T |url=http://ctp.lns.mit.edu/Wilczek_Nature/%2872%29vacuum_metastable.pdf |access-date=2015-10-31}} |

:*[[Vacuum instability]]: Cosmology traditionally has assumed a stable or at least [[metastability|metastable]] universe, but the possibility of a [[false vacuum]] in [[quantum field theory]] implies that the universe at any point in spacetime might spontaneously collapse into a lower energy state (see [[Bubble nucleation]]), a more stable or "true vacuum", which would then expand outward from that point with the speed of light.<ref name="turnerwilczek">{{cite journal |author=M.S. Turner |author2=F. Wilczek |title=Is our vacuum metastable? |journal=Nature |volume=298 |date=1982 |issue=5875 |pages=633–634 |doi=10.1038/298633a0 |bibcode=1982Natur.298..633T |url=http://ctp.lns.mit.edu/Wilczek_Nature/%2872%29vacuum_metastable.pdf |access-date=2015-10-31}} |

||

</ref><ref name="colemandeluccia"> |

</ref><ref name="colemandeluccia"> |

||

{{cite journal |first1=Sidney |last1=Coleman |first2=Frank |last2=De Luccia |title=Gravitational effects on and of vacuum decay |url=http://www.sns.ias.edu/pitp2/2011files/PhysRevD.21.3305.pdf |journal=Physical Review D |date=1980-06-15 |volume=D21 |number=12 |pages=3305–3315 |doi=10.1103/PhysRevD.21.3305 |bibcode=1980PhRvD..21.3305C }} |

{{cite journal |first1=Sidney |last1=Coleman |first2=Frank |last2=De Luccia |title=Gravitational effects on and of vacuum decay |url=http://www.sns.ias.edu/pitp2/2011files/PhysRevD.21.3305.pdf |journal=Physical Review D |date=1980-06-15 |volume=D21 |number=12 |pages=3305–3315 |doi=10.1103/PhysRevD.21.3305 |bibcode=1980PhRvD..21.3305C }} |

||

| Line 366: | Line 366: | ||

{{cite journal |author=M. Stone |title=Lifetime and decay of excited vacuum states |journal=Phys. Rev. D |volume=14 |date=1976 |issue=12 |pages=3568–3573 |doi=10.1103/PhysRevD.14.3568 |bibcode=1976PhRvD..14.3568S }} |

{{cite journal |author=M. Stone |title=Lifetime and decay of excited vacuum states |journal=Phys. Rev. D |volume=14 |date=1976 |issue=12 |pages=3568–3573 |doi=10.1103/PhysRevD.14.3568 |bibcode=1976PhRvD..14.3568S }} |

||

</ref><ref name="P.H. Frampton 1976 1378–1380">{{cite journal |author=P.H. Frampton |title=Vacuum Instability and Higgs Scalar Mass |journal=Phys. Rev. Lett. |volume=37 |date=1976 |issue=21 |pages=1378–1380 |doi=10.1103/PhysRevLett.37.1378 |bibcode=1976PhRvL..37.1378F}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=P.H. Frampton |title=Consequences of Vacuum Instability in Quantum Field Theory |journal=Phys. Rev. |volume=D15 |issue=10 |date=1977 |pages=2922–28 |doi=10.1103/PhysRevD.15.2922 |bibcode=1977PhRvD..15.2922F }}</ref> |

</ref><ref name="P.H. Frampton 1976 1378–1380">{{cite journal |author=P.H. Frampton |title=Vacuum Instability and Higgs Scalar Mass |journal=Phys. Rev. Lett. |volume=37 |date=1976 |issue=21 |pages=1378–1380 |doi=10.1103/PhysRevLett.37.1378 |bibcode=1976PhRvL..37.1378F}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=P.H. Frampton |title=Consequences of Vacuum Instability in Quantum Field Theory |journal=Phys. Rev. |volume=D15 |issue=10 |date=1977 |pages=2922–28 |doi=10.1103/PhysRevD.15.2922 |bibcode=1977PhRvD..15.2922F }}</ref> |

||

In this kind of extreme timescale, extremely rare [[quantum phenomenon|quantum phenomenae]] may also occur that are extremely unlikely to be seen on a timescale smaller than trillions of years. These may also lead to unpredictable changes to the state of the universe which would not be likely to be significant on any smaller timescale. For example, on a timescale of thousands of trillions of years, [[black hole]]s might appear to evaporate almost instantly, uncommon [[quantum tunneling]] phenomenae would appear to be common, and quantum (or other) phenomenae so unlikely that they might occur just once in a trillion years may occur many, many times. |

|||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

Revision as of 12:30, 9 April 2018

| Part of a series on |

| Physical cosmology |

|---|

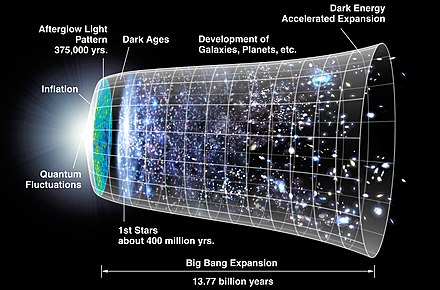

The chronology of the universe describes the history and future of the universe according to Big Bang cosmology. The earliest stages of the universe's existence are estimated as taking place 13.8 billion years ago, with an uncertainty of around 21 million years.[1] For the purposes of this summary, it is convenient to divide the chronology of the universe since it originated, into four parts. It is generally considered meaningless or unclear whether time existed before this chronology:

- 1. The very early universe - the first picosecond (10−12) of cosmic time. It includes the Planck epoch, during which currently understood laws of physics may not apply; the emergence in stages of the four known fundamental interactions or forces - first gravity, and later the strong, weak and electromagnetic interactions; and the expansion of space and supercooling of the still immensely hot universe due to cosmic inflation, which is believed to have been triggered by the separation of the strong and electroweak interaction. Tiny ripples in the universe at this stage are believed to be the basis of large-scale structures that formed much later. Different stages of the very early universe are understood to different extents. The earlier parts are beyond the grasp of practical experiments in particle physics but can be explored through other means.

- 2. The early universe, lasting around 150 million years. During the first 377,000 years, the familiar elementary particles emerged but the universe was too hot for neutral atoms and other structures to form, or photons to travel far, so the universe formed an opaque plasma. For about 6.6 million years (between 10 and 17 million years) the universe's average temperature was suitable for liquid water (273 - 373K); however water did not actually exist. This period ends with an event known as recombination, when the universe cooled enough for the first neutral atoms to form. The newly formed atoms quickly reached their ground state (lowest energy state) by releasing energy in the form of photons, called photon decoupling. As free electrons formed neutral hydrogen, the universe became transparent for the first time. Recombination and decoupling were followed by the "Dark Ages", from 377,000 years to about 150 million years during which the universe was transparent but no stars or other large-scale structures had yet formed. Therefore there were no sources of light. The only photons (electromagnetic radiation, or "light") in the universe were the photons released during decoupling, which we can still detect today as the cosmic microwave background ("CMB"), and 21 cm radio emissions occasionally emitted by hydrogen atoms. The Dark Ages transitioned gradually as structures and stars formed, and only fully came to an end at about 1 billion years.

- 3. Large-scale structure formation, including stellar evolution, galaxy formation and evolution and the formation of galaxy clusters and superclusters, from about 150 million years until about 100 billion years of cosmic time (about 86 billion years in the future). Stars and galaxies form, and large structures emerge, drawn to the foam-like dark matter filaments which have already begun to draw together throughout the universe. Early stars (known as Population III stars) are huge and non-metallic with very short lifetimes compared to most Main Sequence stars we see today, so they commonly finish burning their hydrogen fuel and explode as supernovae after mere millions of years, seeding the universe with heavier elements over repeated generations of early stars. The thin disk of our galaxy began to form at about 5 billion years (8.8 bn years ago),[2] and the solar system formed at about 9.2 billion years (4.6 bn years ago), with the earliest traces of life on Earth emerging by about 10.3 billion years (3.5 bn years ago). This period is understood quite well, but beyond about 100 billion years of cosmic time, uncertainties in current knowledge mean that we are less sure which path our universe will take.

- 4. The far future. At some time the Stelliferous Era will end as stars are no longer being born, and the expansion of the universe will mean that the observable universe becomes limited to local galaxies. There are various scenarios for the far future and ultimate fate of the universe. More exact knowledge of our current universe will allow these to be better understood.

Summary

−13 — – −12 — – −11 — – −10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Earliest stages of chronology shown below (before neutrino decoupling) are an active area of research and based on ideas which are still speculative and subject to modification as scientific knowledge improves.

"Time" column is based on extrapolation of observed metric expansion of space back in the past. For the earliest stages of chronology this extrapolation may be invalid. To give one example, eternal inflation theories propose that inflation lasts forever throughout most of the universe, making the notion of "N seconds since Big Bang" ill-defined.

The radiation temperature refers to the cosmic background radiation and is given by 2.725·(1+z), where z is the redshift.

| Epoch | Time | Redshift | Radiation temperature (Energy} [verification needed] |

Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planck epoch | <10−43 s | >1032 K (>1019 GeV) |

The Planck scale is the scale beyond which current physical theories do not have predictive value. The Planck epoch is the time during which physics is assumed to have been dominated by quantum effects of gravity. | |

| Grand unification epoch |

<10−36 s | >1029 K (>1016 GeV) |

The three forces of the Standard Model are unified (assuming that nature is described by a Grand unification theory). | |

| Inflationary epoch, Electroweak epoch |

<10−32 s | 1028 K ~ 1022 K (1015 ~ 109 GeV) |

Cosmic inflation expands space by a factor of the order of 1026 over a time of the order of 10−33 to 10−32 seconds. The universe is supercooled from about 1027 down to 1022 kelvins.[3] The Strong interaction becomes distinct from the Electroweak interaction. | |

| Quark epoch | 10−12 s ~ 10−6 s | >1012 K (>100 MeV) |

The forces of the Standard Model have separated, but energies are too high for quarks to coalesce into hadrons, instead forming a quark-gluon plasma. These are the highest energies directly observable in experiment in the Large Hadron Collider. | |

| Hadron epoch | 10−6 s ~ 1 s | >1010 K (>1 MeV) |

Quarks are bound into hadrons. A slight matter-antimatter-asymmetry from the earlier phases (baryon asymmetry) results in an elimination of anti-hadrons. | |

| Neutrino decoupling |

1 s | 1010 K (1 MeV) |

Neutrinos cease interacting with baryonic matter. The spherical volume of space which will become the Observable universe is approximately 10 light-years in radius at this time. | |

| Lepton epoch | 1 s ~ 10 s | 1010 K ~ 109 K (1 MeV ~ 100 keV) |

Leptons and anti-leptons remain in thermal equilibrium. | |

| Big Bang nucleosynthesis |

10 s ~ 103 s | 109 K ~ 107 K (100 keV ~ 1 keV) |

Protons and neutrons are bound into primordial atomic nuclei, hydrogen and helium-4. Small amounts of deuterium, helium-3, and lithium-7 are also synthesized. At the end of this epoch, the spherical volume of space which will become the observable universe is about 300 light-years in radius, baryonic matter density is on the order of 4 grams per m3 (about 0.3% of sea level air density) - however, most of energy at this time is in electromagnetic radiation. | |

| Photon epoch | 10 s ~ 1.2·1013 s (380 ka) |

109 K ~ 4000 K (100 keV ~ 0.4 eV) |

The universe consists of a plasma of nuclei, electrons and photons; temperatures remain too high for the binding of electrons to nuclei. | |

| Recombination | 380 ka | 1100 | 4000 K (0.4 eV) |

Electrons and atomic nuclei first become bound to form neutral atoms. Photons are no longer in thermal equilibrium with matter and the Universe first becomes transparent. Recombination lasts for about 100 ka, during which Universe is becoming more and more transparent to photons. The photons of the cosmic microwave background radiation originate at this time. The spherical volume of space which will become the observable universe is 42 million light-years in radius at this time. The baryonic matter density at this time is about 500 million hydrogen and helium atoms per m3, approximately a billion times higher than today. This density corresponds to pressure on the order of 10−17 atm. |

| Dark Ages | 380 ka ~ 150 Ma | 1100 ~ 20 | 4000 K ~ 60 K | The time between recombination and the formation of the first stars. During this time, the only source of photons was hydrogen emitting radio waves at hydrogen line. Freely propagating CMB photons quickly (within about 3 million years) red-shifted to infrared, and Universe was devoid of visible light. |

| Reionization | 150 Ma ~ 1 Ga | 20 ~ 6 | 60 K ~ 19 K | The most distant astronomical objects observable with telescopes date to this period; as of 2016, the most remote galaxy observed is GN-z11, at a redshift of 11.09. The earliest "modern" Population III stars are formed in this period. |

| Galaxy formation and evolution |

1 Ga ~ 10 Ga | 6 ~ 0.4 | 19 K ~ 4 K | Galaxies coalesce into "proto-clusters" from about 1 Ga (z = 6) and into Galaxy clusters beginning at 3 Gy (z = 2.1), and into superclusters from about 5 Gy (z = 1.2), see list of galaxy groups and clusters, list of superclusters. |

| Present time | 13.8 Ga | 0 | 2.7 K | Farthest observable photons at this moment are CMB photons. They arrive from a sphere with the radius of 46 billion light-years. The spherical volume inside it is commonly referred to as Observable universe. |

| Alternative subdivisions of the chronology (overlapping several of the above periods) | ||||

| Matter-dominated era |

47 ka ~ 10 Ga | 3600 ~ 0.4 | 104 K ~ 4 K | During this time, the energy density of matter dominates both radiation density and dark energy, resulting in a decelerated metric expansion of space. |

| Dark-energy- dominated era |

>10 Ga | <0.4 | <4 K | Matter density falls below dark energy density (vacuum energy), and expansion of space begins to accelerate. This time happens to correspond roughly to the time of the formation of the Solar System and the evolutionary history of life. |

| Stelliferous Era | 150 Ma ~ 100 Ga | 20 ~ −0.99 | 60 K ~ 0.03 K | The time between the first formation of Population III stars until the cessation of star formation, leaving all stars in the form of degenerate remnants. |

| Far future | >100 Ga | <−0.99 | <0.1 K | The Stelliferous Era will end as stars eventually die and fewer are born to replace them, leading to a darkening universe. Various theories suggest a number of subsequent possibilities. Assuming proton decay, matter may eventually evaporate into a Dark Era (heat death). Alternatively the universe may collapse in a Big Crunch. Alternative suggestions include a false vacuum catastrophe or a Big Rip as possible ends to the universe. |

Very early universe

Planck epoch

- Times shorter than 10−43 seconds (Planck time)

The Planck epoch is an era in traditional (non-inflationary) big bang cosmology immediately after the event which began our known universe. During this epoch, the temperature and average energies within the universe were so inconceivably high compared to any temperature we can observe today, that subatomic particles could not form (other than perhaps fleetingly), and even the four fundamental forces that shape our universe—electromagnetism, gravitation, weak nuclear interaction, and strong nuclear interaction—were combined and formed one fundamental force. Little is understood about physics at this temperature; different hypotheses propose different scenarios. Traditional big bang cosmology predicts a gravitational singularity before this time, but this theory relies on the theory of general relativity, which is thought to break down for this epoch due to quantum effects.

In inflationary models of cosmology, times before the end of inflation (roughly 10−32 second after the Big Bang) do not follow the same timeline as in traditional big bang cosmology. Models that aim to describe the universe and physics during the Planck epoch are generally speculative and fall under the umbrella of "New Physics". Examples include the Hartle–Hawking initial state, string landscape, string gas cosmology, and the ekpyrotic universe.

Grand unification epoch

- Between 10−43 seconds and 10−36 seconds after the Big Bang[4]

As the universe expanded and cooled, it crossed transition temperatures at which forces separated from each other. These phase transitions can be visualised as similar to condensation and freezing phase transitions of ordinary matter. At certain temperatures/energies, water molecules change their behaviour and structure, and they will behave completely differently. Like steam turning to water, the fields which define our universe's fundamental forces and particles will also completely change how they manifest and operate, when the temperature/energy falls below a certain point. This is not apparent in everyday life, because it only happens at much, much, higher temperatures than we usually see in our present universe.

These phase transitions are believed to be caused by a phenomenon of quantum fields called "symmetry breaking".

In everyday terms, as the universe cools, it becomes possible for the quantum fields that create the forces and particles around us, to completely shift how they behave; by doing so they can settle at lower energy levels and with higher levels of stability. Forces and their interactions can behave very differently above and below a phase transition. For example, in a later epoch, a side effect of one phase transition is that suddenly, many particles that had no mass at all, suddenly have a mass, and a single force begins to manifest as two separate forces.

The grand unification epoch began with a phase transitions of this kind, when gravitation separated from the universal combined gauge force. This caused two forces to now exist: gravity, and an electrostrong interaction. There is no hard evidence yet, that such a combined force existed, but many physicists believe it did. The physics of this electrostrong interaction would be described by a so-called grand unified theory (GUT).

The grand unification epoch ended with a second phase transition, as the electrostrong interaction in turn separated, and began to manifest as two separate forces: the strong force and the electroweak force.

Electroweak epoch

- Between 10−36 seconds (or the end of inflation) and 10−32 seconds after the Big Bang[4]

According to traditional big bang cosmology, the electroweak epoch began 10−36 seconds after the Big Bang, when the temperature of the universe was low enough (1028 K) for the electrostrong interaction to begin to manifest as two separate interactions, called the strong interaction and the electroweak interaction. (The electroweak interaction will also separate later, dividing into the electromagnetic and weak interactions). The exact point where electrostrong symmetry was broken is not certain, because of the very high energies of this event.

In other models of the very early universe, known as inflationary cosmology, the electroweak epoch is said to begin after the inflationary epoch ended, at roughly 10−32 seconds.

Inflationary epoch

- Before ca. 10−32 seconds after the Big Bang

According to inflation theory, at this point, the universe underwent an extremely rapid exponential expansion, which increased the linear dimensions of the early universe by a factor of at least 1026 (and possibly a much larger factor), and so increased its volume by a factor of at least 1078. Expansion by a factor of 1026 is equivalent to expanding an object 1 nanometer (10−9 m, about half the width of a molecule of DNA) in length to one approximately 10.6 light years (about 62 trillion miles) long.

The expansion is thought to have been triggered by the separation of the strong and electroweak interactions which ended the grand unification epoch. One of the theoretical products of this phase transition was a scalar field called the inflaton field. As this field settled into its lowest energy state throughout the universe, it generated an enormous repulsive force that led to a rapid expansion of space itself. This expansion explains various properties of the current universe that are otherwise difficult to account for, including the high degree of homogeneity that is observed in the universe today at large scales, even if the original state of the universe was highly disordered.

It is not known exactly when the inflationary epoch ended, but it is thought to have been between 10−33 and 10−32 seconds after the Big Bang. The rapid expansion of space meant that elementary particles remaining from the grand unification epoch were now distributed very thinly across the universe. However, the huge potential energy of the inflation field was released at the end of the inflationary epoch, as the inflaton field decayed into other particles, known as "reheating". This heating effect led to the universe being repopulated with a dense, hot mixture of quarks, anti-quarks and gluons and marked the start of the electroweak epoch.

In non-traditional versions of Big Bang theory (known as "inflationary" models), inflation ended at a temperature corresponding to roughly 10−32 second after the Big Bang, but this does not imply that the inflationary era lasted less than 10−32 second. To explain the observed homogeneity of the universe, the duration in these models must be longer than 10−32 second. Therefore, in inflationary cosmology, the earliest meaningful time "after the Big Bang" is the time of the end of inflation.

On March 17, 2014, astrophysicists of the BICEP2 collaboration announced the detection of inflationary gravitational waves in the B-mode power spectrum which was interpreted as clear experimental evidence for the theory of inflation.[5][6][7][8][9][10] However, on June 19, 2014, lowered confidence in confirming the cosmic inflation findings was reported [9][11][12] and finally, on February 2, 2015, a joint analysis of data from BICEP2/Keck and Planck satellite concluded that the statistical “significance [of the data] is too low to be interpreted as a detection of primordial B-modes” and can be attributed mainly to polarized dust in the Milky Way.[13][14][15][16]

Baryogenesis

There is currently insufficient observational evidence to explain why the universe contains far more baryons than antibaryons. A candidate explanation for this phenomenon must allow the Sakharov conditions to be satisfied at some time after the end of cosmological inflation. While particle physics suggests asymmetries under which these conditions are met, these asymmetries are too small empirically to account for the observed baryon-antibaryon asymmetry of the universe.

Supersymmetry breaking (speculative)

If supersymmetry is a property of our universe, then it must be broken at an energy that is no lower than 1 TeV, the electroweak symmetry scale. The masses of particles and their superpartners would then no longer be equal, which could explain why no superpartners of known particles have ever been observed.

Electroweak symmetry breaking

- 10−12 seconds after the Big Bang

As the universe's temperature falls below a certain very high energy level (known as the electroweak scale), a third symmetry breaking occurs. So far as we know and believe, it was the final symmetry breaking event in the formation of our universe. It is believed that the Higgs field spontaneously acquires a vacuum expectation value, which breaks electroweak gauge symmetry. This happens at energies believed to be of the order of 246 GeV,[17][verification needed] and has two related effects:

- Via the Higgs mechanism, all elementary particles interacting with the Higgs field become massive, having been massless at higher energy levels.

- As a side-effect, the weak force and electromagnetic force, and their respective bosons (the W and Z bosons and photon) now begin to manifest differently in the present universe. Before electroweak symmetry breaking these bosons were all massless particles and interacted over long distances, but at this point the W and Z bosons abruptly become massive particles only interacting over distances smaller than the size of an atom, while the photon remains massless and remains a long-distance interaction.

After electroweak symmetry breaking, the fundamental interactions we know of - gravitation, electromagnetism, the strong interaction and the weak interaction - have all taken their present forms, and fundamental particles have mass, but the temperature of the universe is still too high to allow the formation of many fundamental particles we now see in the universe.

Early universe

After cosmic inflation ends, the universe is filled with a quark–gluon plasma. From this point onwards the physics of the early universe is better understood, and the energies involved in the Quark epoch are directly amenable to experiment.

The quark epoch

- Between 10−12 second and 10−6 second after the Big Bang

The quark epoch began approximately 10−12 seconds after the Big Bang. This was the period in the evolution of the early universe immediately after electroweak symmetry breaking, when the fundamental interactions of gravitation, electromagnetism, the strong interaction and the weak interaction had taken their present forms, but the temperature of the universe was still too high to allow quarks to bind together to form hadrons.

During the quark epoch the universe was filled with a dense, hot quark–gluon plasma, containing quarks, leptons and their antiparticles. Collisions between particles were too energetic to allow quarks to combine into mesons or baryons.

The quark epoch ended when the universe was about 10−6 seconds old, when the average energy of particle interactions had fallen below the binding energy of hadrons.

Hadron epoch

- Between 10−6 second and 1 second after the Big Bang

The quark–gluon plasma that composes the universe cools until hadrons, including baryons such as protons and neutrons, can form. At approximately 1 second after the Big Bang neutrinos decouple and begin traveling freely through space. This cosmic neutrino background, while unlikely to ever be observed in detail since the neutrino energies are very low, is analogous to the cosmic microwave background that was emitted much later. (See above regarding the quark–gluon plasma, under the String Theory epoch.) However, there is strong indirect evidence that the cosmic neutrino background exists, both from Big Bang nucleosynthesis predictions of the helium abundance, and from anisotropies in the cosmic microwave background.

Lepton epoch

- Between 1 second and 10 seconds after the Big Bang

The majority of hadrons and anti-hadrons annihilate each other at the end of the hadron epoch, leaving leptons and anti-leptons dominating the mass of the universe. Approximately 10 seconds after the Big Bang the temperature of the universe falls to the point at which new lepton/anti-lepton pairs are no longer created and most leptons and anti-leptons are eliminated in annihilation reactions, leaving a small residue of leptons.[18]

Photon epoch

- Between 10 seconds and 380,000 years after the Big Bang

After most leptons and anti-leptons are annihilated at the end of the lepton epoch the energy of the universe is dominated by photons. These photons are still interacting frequently with charged protons, electrons and (eventually) nuclei, and continue to do so for the next 380,000 years.

Nucleosynthesis

- Between 3 minutes and 20 minutes after the Big Bang[19]

During the photon epoch the temperature of the universe falls to the point where atomic nuclei can begin to form. Protons (hydrogen ions) and neutrons begin to combine into atomic nuclei in the process of nuclear fusion. Free neutrons combine with protons to form a hydrogen isotope, deuterium. Deuterium rapidly fuses into helium-4. Nucleosynthesis only lasts for about seventeen minutes, by which time the temperature and density of the universe has fallen to the point where nuclear fusion cannot continue. By this time, all neutrons have been incorporated into helium nuclei. This leaves about three times more hydrogen than helium-4 (by mass) and only trace quantities of lithium and other light nuclei.

Matter domination

- 70,000 years after the Big Bang

At this time, the densities of non-relativistic matter (atomic nuclei) and relativistic radiation (photons) are equal. The Jeans length, which determines the smallest structures that can form (due to competition between gravitational attraction and pressure effects), begins to fall and perturbations, instead of being wiped out by free-streaming radiation, can begin to grow in amplitude.

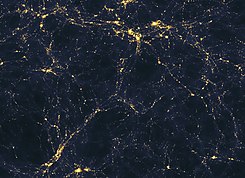

According to the Lambda-CDM model, by this stage, the matter in the universe is around 84.5% cold dark matter and 15.5% "ordinary" matter. There is overwhelming evidence that dark matter exists and dominates our universe, but since the exact nature of dark matter is still not understood, Big Bang theory does not presently cover any stages in its formation.

From this point on, and for several billion years to come, the presence of dark matter accelerates the formation of structure in our universe. In the early universe, dark matter gradually gathers in huge filaments under the effects of gravity. This amplifies the tiny inhomogeneities in the density of the universe which was left by cosmic inflation. Over time, slightly denser regions become denser and slightly rarefied regions become more rarefied. Ordinary matter eventually gathers together faster than it would otherwise do, because of the presence of these concentrations of dark matter.

Recombination and photon decoupling

- ca. 377,000 years after the Big Bang

Before decoupling, the baryonic matter in the universe was at a temperature where it formed a hot ionized plasma. Most of the photons in the universe interacted with electrons and protons, and could not travel long distances without interacting with ionized particles. As a result, the universe was opaque or "foggy". Although there was light, it was not possible to see, nor can we observe that light through telescopes.

As the universe cools, free electrons begin to combine with the hydrogen and helium nuclei to form neutral hydrogen and helium atoms. This is thought to have occurred about 377,000 years after the Big Bang.[22] This process is relatively fast (and faster for the helium than for the hydrogen), and is known as recombination.[23] The name is slightly inaccurate and is given for historical reasons: in fact the electrons were combining for the first time.

Because direct combinations to the ground state (lowest energy) of hydrogen are very inefficient, these hydrogen atoms generally form with the electrons in a high energy state, and the electrons quickly transition to their low energy state by emitting photons. This release of photons as hydrogen atoms settle, is known as photon decoupling. Some of these photons are captured by other hydrogen atoms, the remainder remain as photons. By the end of recombination, most of the protons in the universe have formed neutral atoms. Therefore, the photons' mean free path becomes effectively infinite and the photons released can now travel freely over long distances (see Thomson scattering). The change from charged to neutral particles meant that for the first time, the universe became transparent to visible light, radio waves and other electromagnetic radiation for the first time in its history.

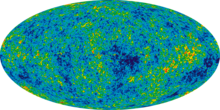

The photons released by the newly formed hydrogen atoms initially had a temperature/energy of around ~ 4000 K (visible red light). Over billions of years since decoupling, as the universe has expanded, they have red-shifted from visible red light to radio waves (microwave radiation corresponding to a temperature of about 2.7 K). They can still be detected as radio waves today. They form the cosmic microwave background ("CMB"), and they provide crucial evidence of the early universe and how it developed.

Around the same time as recombination, existing pressure waves within the electron-baryon plasma – known as baryon acoustic oscillations – became embedded in the distribution of matter as it condensed, giving rise to a very slight preference in distribution of large-scale objects. Therefore, the cosmic microwave background is a picture of the universe at the end of this epoch including the tiny fluctuations generated during inflation (see diagram), and the spread of objects such as galaxies in the universe is an indication of the scale and size of the universe as it developed over time.[24]

Dark Ages

- ca. 380 thousand to 150 million years after the Big Bang, fully ending around 1000 million years after the Big Bang[25]

The "Dark Ages" span a period from about 380,000 years after the Big Bang, when the universe had cooled enough to allow light to travel long distances, but light-producing structures such as stars and galaxies did not yet exist. During the Dark Ages, the temperature of the universe cooled from some 4000 K down to about 60 K.

During this period, the universe was "dark" in several ways. Before the start of the Dark Ages, it was opaque because it was filled with a hot plasma which prevented light from travelling far. The effect was similar to being filled with a glowing fog. During recombination/decoupling, the plasma cooled and formed neutral atoms, and the universe became transparent for the first time. However it was still "dark" for many millions of years, because stars, galaxies and other light-giving structures did not yet exist. Only two sources of photons existed: the photons released during recombination/decoupling, as hydrogen atoms formed, which we can still detect today as the cosmic microwave background (CMB), and photons occasionally released by neutral hydrogen atoms, known as the 21 cm spin line of neutral hydrogen. There was no other light since stars and galaxies had not yet formed. The Dark Ages ended gradually as structure formed, during a period from around 150 million years after the Big Bang to around 1 billion (1000 million) years.

The October 2010 discovery of UDFy-38135539, the first observed galaxy to have existed during the following reionization epoch, gives us a window into these times. The galaxy earliest in this period observed and thus also the most distant galaxy ever observed is currently on the record of Leiden University's Richard J. Bouwens and Garth D. Illingsworth from UC Observatories/Lick Observatory. They found the galaxy UDFj-39546284 to be at a time some 480 million years after the Big Bang or about halfway through the Cosmic Dark Ages at a distance of about 13.2 billion light-years. More recently, the UDFy-38135539, EGSY8p7 and GN-z11 galaxies were found to be around 380–550 million years after the Big Bang and at a distance of around 13.4 billion light-years.[26] There is also currently an observational effort underway to detect the faint 21 cm spin line radiation, as it is in principle an even more powerful tool than the cosmic microwave background for studying the early universe.

The Dark Ages ended gradually, - the first structures formed around 150 million years after the Big Bang, and the Dark Ages were fully ended by around 1000 million (1 billion) years after the Big Bang.

Habitable epoch

- ca. 10-17 million years after the Big Bang

The background temperature was between 373 K and 273 K, a temperature compatible with liquid water and common biological chemical reactions, during a period of about 6.6 million years, from about 10 to 17 million after the Big Bang (redshift 137–100). Loeb (2014) speculated that primitive life might in principle have appeared during this window, which he called "the Habitable Epoch of the Early Universe".[27][28][29]

However at this time, the only atoms that existed were hydrogen, helium and small traces of other elements, mainly the next heaviest element, lithium. Water is made of hydrogen and oxygen, and as almost no oxygen existed, the universe did not actually contain water at this time, even though its average temperature was appropriate for water to exist. For the same reason there was no carbon, or other elements needed for organic chemistry to occur. All known forms of organic reaction and life require heavier elements than hydrogen, helium or even lithium. Therefore although the temperature was suitable, as far as we can tell, life could not have existed during this period.

Large-scale structure formation

Structure formation in the big bang model proceeds hierarchically, with smaller structures forming before larger ones. The first structures to form are quasars, which are thought to be bright, early active galaxies, and population III stars. Before this epoch, the evolution of the universe could be understood through linear cosmological perturbation theory: that is, all structures could be understood as small deviations from a perfect homogeneous universe. This is computationally relatively easy to study. At this point non-linear structures begin to form, and the computational problem becomes much more difficult, involving, for example, N-body simulations with billions of particles.

Reionization and first structures

- Around 150 million to 1 billion years after the Big Bang

The first stars, dwarf galaxies and quasars gradually form due to gravitational collapse. The intense radiation they emit reionizes much of the surrounding universe; splitting the neutral hydrogen atoms back into a plasma of free electrons and protons for the first time since recombination and decoupling.

Observations have narrowed down the period of time during which reionization took place, but the source of the photons that caused reionization is still not completely certain. To ionize neutral hydrogen, an energy larger than 13.6 eV is required, which corresponds to ultraviolet photons with a wavelength of 91.2 nm or shorter, implying that the sources must have produced significant amount of ultraviolet and higher energy. Protons and electrons will recombine if energy is not continuously provided to keep them apart, which also sets limits on how numerous the sources where and their longevity.[30] With these constraints, it is expected that quasars and first generation stars and galaxies were the main sources of energy.[31] The current leading candidates from most to least significant are currently believed to be population III stars (the earliest stars) (possibly 70%),[32][33] dwarf galaxies (very early small high-energy galaxies) (possibly 30%),[34] and a contribution from quasars (a class of active galactic nuclei).[30][35][36]

However by this time, matter had become far more spread out due to the ongoing expansion of the universe. Although the neutral hydrogen atoms were again ionized, the plasma was much more thin and diffuse, and photons were much less likely to be scattered. Despite being reionized, the universe remained largely transparent during reionization. As the universe continued to cool and expand, reionization gradually ended.

Star formation

The first stars, known as Population III stars, are also responsible for turning the few light elements that were formed in the Big Bang (hydrogen, helium and small amounts of lithium) into many heavier elements. They are huge and non-metallic (no elements except hydrogen), and have very short lifetimes compared to most Main Sequence stars we see today, so they commonly finish burning their hydrogen fuel and explode as supernovae after mere millions of years, seeding the universe with heavier elements over repeated generations of early stars.

As yet, no Population III stars have been found, so our understanding of them is based on computational models of their formation and evolution. Fortunately, observations of the Cosmic Microwave Background radiation can be used to date when star formation began in earnest. Analysis of such observations made by the European Space Agency's Planck telescope in 2016 concluded that the first generation of stars formed 700 million years after the Big Bang.[37]

Galaxies, clusters and superclusters

Large volumes of matter collapse to form a galaxy. Population II stars are formed early on in this process, with Population I stars formed later.

Johannes Schedler's project has identified a quasar CFHQS 1641+3755 at 12.7 billion light-years away,[39] when the universe was just 7% of its present age.

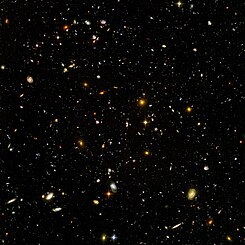

On July 11, 2007, using the 10-metre Keck II telescope on Mauna Kea, Richard Ellis of the California Institute of Technology at Pasadena and his team found six star forming galaxies about 13.2 billion light years away and therefore created when the universe was only 500 million years old.[40] Only about 10 of these extremely early objects are currently known.[41] More recent observations have shown these ages to be shorter than previously indicated. The most distant galaxy observed as of October 2013 has been reported to be 13.1 billion light years away.[42]

The Hubble Ultra Deep Field shows a number of small galaxies merging to form larger ones, at 13 billion light years, when the universe was only 5% its current age.[43] This age estimate is now believed to be slightly shorter.[42]

Based upon the emerging science of nucleocosmochronology, the Galactic thin disk of the Milky Way is estimated to have been formed 8.8 ± 1.7 billion years ago.[44]

Gravitational attraction pulls galaxies towards each other to form groups, clusters and superclusters.

Far future and ultimate fate

The universe has existed for around 13.8 billion years, and we believe that we understand it well enough to predict its large-scale development for many billions of years into the future - perhaps as much as 100 billion years of cosmic time (about 86 billion years from now). Beyond that, we need better understandings, to make accurate predictions. Therefore the universe could follow a variety of different paths beyond this time.

There are several competing scenarios for the possible long-term evolution of the universe. Which of them will happen, if any, depends on the precise values of physical constants such as the cosmological constant, the possibility of proton decay, and the natural laws beyond the Standard Model.

In the very long term (after many more billion years of cosmic time), the Stelliferous Era will end, as stars cease to be born. If the expansion of the universe continues as expected, eventually all but the nearest galaxies will be carried away from us by the expansion of space at such a velocity that our observable universe will be limited to our own gravitationally bound local galactic cluster. Beyond this, if the universe continues to expand and stays in its present form, all objects in the universe will cool and (with the possible exception of protons) gradually decompose back to their constituent particles and then into subatomic particles and very low level photons and other fundamental particles, by a variety of possible processes. But this will take a duration of time that is almost inconceivable to most people, compared to which the entire 13.8 billion years of the universe would seem like an tiny instant in time.

Ultimately, in the extreme future, the following scenarios have been proposed for the ultimate fate of the universe.

- Heat Death: In the case of indefinitely continuing metric expansion of space, the energy density in the universe will decrease until, after an estimated time of 101000 years, it reaches thermodynamic equilibrium and no more structure will be possible. This will happen only after an extremely long time because first, all matter will collapse into black holes, which will then evaporate extremely slowly via Hawking radiation. The universe in this scenario will cease to be able to support life much earlier than this, after some 1014 years or so, when star formation ceases.[45], §IID. In some grand unified theories, proton decay after at least 1034 years will convert the remaining interstellar gas and stellar remnants into leptons (such as positrons and electrons) and photons. Some positrons and electrons will then recombine into photons.[45], §IV, §VF. In this case, the universe has reached a high-entropy state consisting of a bath of particles and low-energy radiation. It is not known however whether it eventually achieves thermodynamic equilibrium.[45], §VIB, VID. The hypothesis of a universal heat death stems from the 1850s ideas of William Thomson (Lord Kelvin)[46] who extrapolated the theory of heat views of mechanical energy loss in nature, as embodied in the first two laws of thermodynamics, to universal operation.

- Big Rip: For sufficiently large values for the dark energy content of the universe, the expansion rate of the universe will continue to increase without limit. Gravitationally bound systems, such as clusters of galaxies, galaxies, and ultimately the Solar System will be torn apart. Eventually the expansion will be so rapid as to overcome the electromagnetic forces holding molecules and atoms together. Finally even atomic nuclei will be torn apart and the universe as we know it will end in an unusual kind of gravitational singularity.

- Big Crunch: In the opposite of the "Big Rip" scenario, the metric expansion of space would at some point be reversed and the universe would contract towards a hot, dense state. This is a required element of oscillatory universe scenarios, such as the cyclic model, although a Big Crunch does not necessarily imply an oscillatory universe. Current observations suggest that this model of the universe is unlikely to be correct, and the expansion will continue or even accelerate.

- Vacuum instability: Cosmology traditionally has assumed a stable or at least metastable universe, but the possibility of a false vacuum in quantum field theory implies that the universe at any point in spacetime might spontaneously collapse into a lower energy state (see Bubble nucleation), a more stable or "true vacuum", which would then expand outward from that point with the speed of light.[47][48][49][50][51]

In this kind of extreme timescale, extremely rare quantum phenomenae may also occur that are extremely unlikely to be seen on a timescale smaller than trillions of years. These may also lead to unpredictable changes to the state of the universe which would not be likely to be significant on any smaller timescale. For example, on a timescale of thousands of trillions of years, black holes might appear to evaporate almost instantly, uncommon quantum tunneling phenomenae would appear to be common, and quantum (or other) phenomenae so unlikely that they might occur just once in a trillion years may occur many, many times.

See also

- Cosmic Calendar (age of universe scaled to a single year)

- Cyclic model

- Dark-energy-dominated era

- Dyson's eternal intelligence

- Entropy (arrow of time)

- Graphical timeline from Big Bang to Heat Death

- Graphical timeline of the Big Bang

- Graphical timeline of the Stelliferous Era

- Illustris project

- Matter-dominated era

- Radiation-dominated era

- Timeline of the far future

- Ultimate fate of the universe

References

- ^ The Planck Collaboration in 2015 published the estimate of 13.799 ± 0.021 billion years ago (68% confidence interval). See Table 4 on page 31 of pdf. Planck Collaboration (2015). "Planck 2015 results. XIII. Cosmological parameters". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 594 (13): A13. arXiv:1502.01589. Bibcode:2016A&A...594A..13P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201525830.

- ^ del Peloso, E. F. (2005). "The age of the Galactic thin disk from Th/Eu nucleocosmochronology. III. Extended sample". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 440 (3): 1153–1159. arXiv:astro-ph/0506458. Bibcode:2005A&A...440.1153D. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20053307.

- ^ Guth, "Phase transitions in the very early universe", in: Hawking, Gibbon, Siklos (eds.), The Very Early Universe (1985).

- ^ a b Ryden B: "Introduction to Cosmology", p. 196 Addison-Wesley 2003

- ^ Staff (17 March 2014). "BICEP2 2014 Results Release". National Science Foundation. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ Clavin, Whitney (17 March 2014). "NASA Technology Views Birth of the Universe". NASA. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (March 17, 2014). "Space Ripples Reveal Big Bang's Smoking Gun". The New York Times. Retrieved March 17, 2014.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (March 24, 2014). "Ripples From the Big Bang". New York Times. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ a b Ade, P.A.R. (BICEP2 Collaboration); et al. (June 19, 2014). "Detection of B-Mode Polarization at Degree Angular Scales by BICEP2" (PDF). Physical Review Letters. 112: 241101. arXiv:1403.3985. Bibcode:2014PhRvL.112x1101A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.112.241101. PMID 24996078. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|format= - ^ BICEP2 News | Not Even Wrong

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (June 19, 2014). "Astronomers Hedge on Big Bang Detection Claim". New York Times. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (June 19, 2014). "Cosmic inflation: Confidence lowered for Big Bang signal". BBC News. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

- ^ BICEP2/Keck, Planck Collaborations (2015). "A Joint Analysis of BICEP2/Keck Array and Planck Data". Physical Review Letters. 114 (10): 101301. arXiv:1502.00612. Bibcode:2015PhRvL.114j1301B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.114.101301. PMID 25815919.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Clavin, Whitney (30 January 2015). "Gravitational Waves from Early Universe Remain Elusive". NASA. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (30 January 2015). "Speck of Interstellar Dust Obscures Glimpse of Big Bang". New York Times. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ^ "Gravitational waves from early universe remain elusive". Science Daily. 31 January 2015. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ^ The particular number 246 GeV is taken to be the vacuum expectation value of the Higgs field (where is the Fermi coupling constant).

- ^ The Timescale of Creation Archived 2009-07-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Detailed timeline of Big Bang nucleosynthesis processes

- ^ Gannon, Megan (December 21, 2012). "New 'Baby Picture' of Universe Unveiled". Space.com. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ^ Bennett, C.L.; Larson, L.; Weiland, J.L.; Jarosk, N.; Hinshaw, N.; Odegard, N.; Smith, K.M.; Hill, R.S.; Gold, B.; Halpern, M.; Komatsu, E.; Nolta, M.R.; Page, L.; Spergel, D.N.; Wollack, E.; Dunkley, J.; Kogut, A.; Limon, M.; Meyer, S.S.; Tucker, G.S.; Wright, E.L. (2013). "Nine-Year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) Observations: Final Maps and Results". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 208: 20. arXiv:1212.5225. Bibcode:2013ApJS..208...20B. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/208/2/20.

- ^ Hinshaw, G.; et al. (2009). "Five-Year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) Observations: Data Processing, Sky Maps, and Basic Results" (PDF). Astrophysical Journal Supplement. 180 (2): 225–245. arXiv:0803.0732. Bibcode:2009ApJS..180..225H. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/180/2/225.

- ^ Mukhanov, V: "Physical foundations of Cosmology", p. 120, Cambridge 2005

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (2012-11-13). "Quasars illustrate dark energy's roller coaster ride". BBC News. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ^ www.sciam.com. "The Dark Ages" (PDF). pp. physically 4–5 (listed as 48–49).

- ^ Wall, Mike (December 12, 2012). "Ancient Galaxy May Be Most Distant Ever Seen". Space.com. Retrieved December 12, 2012.

- ^ Loeb, Abraham (October 2014). "The Habitable Epoch of the Early Universe". International Journal of Astrobiology. 13 (04): 337–339. arXiv:1312.0613. Bibcode:2014IJAsB..13..337L. doi:10.1017/S1473550414000196. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- ^ Loeb, Abraham (December 2013). "The Habitable Epoch of the Early Universe". arXiv:1312.0613. Bibcode:2014IJAsB..13..337L. doi:10.1017/S1473550414000196.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Dreifus, Claudia (2 December 2014). "Much-Discussed Views That Go Way Back - Avi Loeb Ponders the Early Universe, Nature and Life". New York Times. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ a b Piero Madau; et al. (1999). "Radiative Transfer in a Clumpy Universe. III. The Nature of Cosmological Ionizing Source". The Astrophysical Journal. 514 (2): 648–659. arXiv:astro-ph/9809058. Bibcode:1999ApJ...514..648M. doi:10.1086/306975.

- ^ Loeb; Barkana (2000). "In the Beginning: The First Sources of Light and the Reionization of the Universe". Physics Reports. 349 (2): 125–238. arXiv:astro-ph/0010468. Bibcode:2001PhR...349..125B. doi:10.1016/S0370-1573(01)00019-9.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Nickolay Gnedin; Jeremiah Ostriker (1997). "Reionization of the Universe and the Early Production of Metals". Astrophysical Journal. 486 (2): 581–598. arXiv:astro-ph/9612127. Bibcode:1997ApJ...486..581G. doi:10.1086/304548.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Limin Lu; et al. (1998). "The Metal Contents of Very Low Column Density Lyman-alpha Clouds: Implications for the Origin of Heavy Elements in the Intergalactic Medium". arXiv:astro-ph/9802189.

- ^ R.J.Bouwens; et al. (2012). "Lower-luminosity Galaxies Could Reionize the Universe: Very Steep Faint-end Slopes to the UV Luminosity Functions at z >= 5-8 from the HUDF09 WFC3/IR Observations". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 752 (1): L5. arXiv:1105.2038v4. Bibcode:2012ApJ...752L...5B. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/752/1/L5.

- ^ Paul Shapiro; Mark Giroux (1987). "Cosmological H II regions and the photoionization of the intergalactic medium". The Astrophysical Journal. 321: 107–112. Bibcode:1987ApJ...321L.107S. doi:10.1086/185015.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Xiaohu Fan; et al. (2001). "A Survey of z>5.8 Quasars in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. I. Discovery of Three New Quasars and the Spatial Density of Luminous Quasars at z~6". The Astronomical Journal. 122 (6): 2833–2849. arXiv:astro-ph/0108063. Bibcode:2001AJ....122.2833F. doi:10.1086/324111.

- ^ Planck: First Stars Formed Later Than We Thought; NASA.gov

- ^ Andrew Pontzen and Hiranya Peiris, Illuminating illumination: what lights up the universe?, UCLA press release, 27 August 2014.

- ^ APOD: 2007 September 6 - Time Tunnel

- ^ "New Scientist" 14 July 2007

- ^ HET Helps Astronomers Learn Secrets of One of Universe's Most Distant Objects

- ^ a b Scientists confirm most distant galaxy ever

- ^ APOD: 2004 March 9 – The Hubble Ultra Deep Field

- ^ Eduardo F. del Peloso a1a, Licio da Silva a1, Gustavo F. Porto de Mello and Lilia I. Arany-Prado (2005), "The age of the Galactic thin disk from Th/Eu nucleocosmochronology: extended sample" (Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union (2005), 1: 485-486 Cambridge University Press)

- ^ a b c A dying universe: the long-term fate and evolution of astrophysical objects, Fred C. Adams and Gregory Laughlin, Reviews of Modern Physics 69, #2 (April 1997), pp. 337–372. Bibcode:1997RvMP...69..337A. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.69.337.

- ^ Thomson, William. (1851). "On the Dynamical Theory of Heat, with numerical results deduced from Mr Joule's equivalent of a Thermal Unit, and M. Regnault's Observations on Steam." Excerpts. [§§1-14 & §§99-100], Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, March, 1851; and Philosophical Magazine IV. 1852, [from Mathematical and Physical Papers, vol. i, art. XLVIII, pp. 174]

- ^ M.S. Turner; F. Wilczek (1982). "Is our vacuum metastable?" (PDF). Nature. 298 (5875): 633–634. Bibcode:1982Natur.298..633T. doi:10.1038/298633a0. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ Coleman, Sidney; De Luccia, Frank (1980-06-15). "Gravitational effects on and of vacuum decay" (PDF). Physical Review D. D21 (12): 3305–3315. Bibcode:1980PhRvD..21.3305C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.21.3305.

- ^ M. Stone (1976). "Lifetime and decay of excited vacuum states". Phys. Rev. D. 14 (12): 3568–3573. Bibcode:1976PhRvD..14.3568S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.14.3568.

- ^ P.H. Frampton (1976). "Vacuum Instability and Higgs Scalar Mass". Phys. Rev. Lett. 37 (21): 1378–1380. Bibcode:1976PhRvL..37.1378F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.37.1378.

- ^ P.H. Frampton (1977). "Consequences of Vacuum Instability in Quantum Field Theory". Phys. Rev. D15 (10): 2922–28. Bibcode:1977PhRvD..15.2922F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.15.2922.

External links

- PBS Online (2000). From the Big Bang to the End of the Universe – The Mysteries of Deep Space Timeline. Retrieved March 24, 2005.

- Schulman, Eric (1997). The History of the Universe in 200 Words or Less. Retrieved March 24, 2005.

- Deep Time: Crash Course Astronomy #45. Retrieved October 2, 2016.

- Space Telescope Science Institute Office of Public Outreach (2005). Home of the Hubble Space Telescope. Retrieved March 24, 2005.

- Fermilab graphics (see "Energy time line from the Big Bang to the present" and "History of the Universe Poster")

- Exploring Time from Planck time to the lifespan of the Universe

- Cosmic Evolution is a multi-media web site that explores the cosmic-evolutionary scenario from big bang to humankind.

- Astronomers' first detailed hint of what was going on less than a trillionth of a second after time began

- The Universe Adventure

- Cosmology FAQ, Professor Edward L. Wright, UCLA

- Sean Carroll on the arrow of time (Part 1), The origin of the universe and the arrow of time, Sean Carroll, video, CHAST 2009, Templeton, Faculty of science, University of Sydney, November 2009, TED.com

- A Universe From Nothing, video, Lawrence Krauss, AAI 2009, YouTube.com

- Once Upon A Universe - Story of the Universe told in 13 chapters. Science communication site supported by STFC.

- Cosmic Evolution through Time - an interactive timeline explains the main events in the history of our Universe