Julian Assange: Difference between revisions

Off2riorob (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Ghostofnemo (talk | contribs) →Alleged sex offences: some claim sex charges fabricated as part of CIA plot |

||

| Line 102: | Line 102: | ||

One of Assange's lawyers, [[Mark Stephens (solicitor)|Mark Stephens]], has compared the legal proceedings to a [[show trial]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.rte.ie/news/2010/1214/wikileaks.html |title=Sweden challenges Julian Assange bail decision - RTÉ News |publisher=Rte.ie |date= |accessdate=2010-12-16}}</ref> Assange's defense team also includes human rights lawyers [[Geoffrey Robertson]] QC<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.theage.com.au/world/geoffrey-robertson-to-defend-assange-20101207-18oc6.html |title=Geoffrey Robertson to defend Assange |publisher=Theage.com.au |date=2010-12-08 |accessdate=2010-12-16}}</ref> and solicitor Jennifer Robinson.<ref>{{cite web|author=|url=http://www.google.com/hostednews/afp/article/ALeqM5j46K4cMwoVbD8InbfwFwU3eiceIg?docId=CNG.9a1f542d490713273e28084042762a68.691 |title=Assange moved to prison's segregation unit |publisher=Google.com |date= |accessdate=2010-12-16}}</ref> |

One of Assange's lawyers, [[Mark Stephens (solicitor)|Mark Stephens]], has compared the legal proceedings to a [[show trial]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.rte.ie/news/2010/1214/wikileaks.html |title=Sweden challenges Julian Assange bail decision - RTÉ News |publisher=Rte.ie |date= |accessdate=2010-12-16}}</ref> Assange's defense team also includes human rights lawyers [[Geoffrey Robertson]] QC<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.theage.com.au/world/geoffrey-robertson-to-defend-assange-20101207-18oc6.html |title=Geoffrey Robertson to defend Assange |publisher=Theage.com.au |date=2010-12-08 |accessdate=2010-12-16}}</ref> and solicitor Jennifer Robinson.<ref>{{cite web|author=|url=http://www.google.com/hostednews/afp/article/ALeqM5j46K4cMwoVbD8InbfwFwU3eiceIg?docId=CNG.9a1f542d490713273e28084042762a68.691 |title=Assange moved to prison's segregation unit |publisher=Google.com |date= |accessdate=2010-12-16}}</ref> |

||

Some observers believe that the sex charges against Assange may have been fabricated as part of a [[Central Intelligence Agency]] plot to either discredit Assange or to extradite him to the U.S. to face [[[espionage]] charges.<ref>{{cite web| url=http://www.slate.com/id/2277407/| author=Christopher Beam| title=The Spy Who Said She Loved Me| publisher=Slate| date=December 9, 2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite news| url=http://daily.bhaskar.com/article/the-honeytrap-that-snared-assange-1634136.html?PRV=| title=The 'honeytrap' that snared Assange| publisher=Dailybhaskar.in| date=December 9, 2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite web| url=http://www.thenation.com/article/157127/swedish-state-trial-assange-case| author=Tom Hayden| title=Swedish State on Trial in Assange Case?| publisher=The Nation| date=December 15, 2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite news| url=http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1336291/Wikileaks-Julian-Assanges-2-night-stands-spark-worldwide-hunt.html#ixzz17RpxuchA| author=Richard Pendlebury| title=The Wikileaks sex files: How two one-night stands sparked a worldwide hunt for Julian Assange| publisher=Daily Mail - MailOnline| date=December 7, 2010}}</ref> |

|||

== Support and praise == |

== Support and praise == |

||

Revision as of 13:58, 17 December 2010

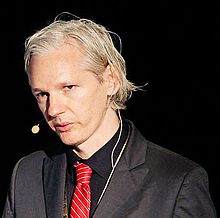

Julian Assange | |

|---|---|

Assange in 2010 | |

| Born | 3 July 1971[1][2][3] Townsville, Queensland, Australia |

| Nationality | Australian |

| Alma mater | University of Melbourne |

| Occupation(s) | Editor-in-chief and spokesperson for WikiLeaks |

| Children | Daniel Assange[4] |

| Awards | Economist Freedom of Expression Award (2008) Amnesty International UK Media Award (2009) Sam Adams Award (2010) |

Julian Paul Assange (/[invalid input: 'icon']əˈsɑːnʒ/ ə-SAHNZH; born 3 July 1971) is an Australian journalist,[5][6][7] publisher,[8][9] and Internet activist. He is the spokesperson and editor in chief for WikiLeaks, a whistleblower website and conduit for news leaks. Before working with the website, he was a hacker, university student and computer programmer.[10] He has lived in several countries, and has made occasional public appearances to speak about freedom of the press, censorship, and investigative journalism.

Assange founded the WikiLeaks website in 2006 and serves on its advisory board. He has been involved in publishing material about extrajudicial killings in Kenya, for which he won the 2009 Amnesty International Media Award. He has also published material about toxic waste dumping in Africa, Church of Scientology manuals, Guantanamo Bay procedures, and banks such as Kaupthing and Julius Baer.[11] In 2010, he published classified details about US involvement in the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Then, on 28 November 2010, WikiLeaks and its five media partners began publishing secret US diplomatic cables.[12] The White House has called Assange's release of the diplomatic cables "reckless and dangerous".[13]

For his work with WikiLeaks, Assange received the 2008 Economist Freedom of Expression Award and the 2010 Sam Adams Award. Utne Reader named him as one of the "25 Visionaries Who Are Changing Your World". In 2010, New Statesman ranked Assange twenty-third among the "The World's 50 Most Influential Figures", and he was given the Readers' Choice award for Time magazine's 2010 Person of the Year.[14]

Assange is wanted for questioning in Sweden in regards to sexual offences, and is currently on bail and under house arrest in England pending an extradition hearing.[15] He has denied the allegations and has pledged to clear his name.[16][17]

Early life

Assange was born in Townsville, Queensland, and spent much of his youth living on Magnetic Island.[18]

When he was one year old, his mother Christine married theatre director Brett Assange, who gave him his surname.[2][19] Brett and Christine Assange ran a touring theatre company. His stepfather, Julian's first "real dad", described Julian as "a very sharp kid" with "a keen sense of right and wrong". "He always stood up for the underdog,... he was always very angry about people ganging up on other people."[19]

In 1979, his mother remarried; her new husband was a musician who belonged to a controversial New Age group led by Anne Hamilton-Byrne. The couple had a son, but broke up in 1982 and engaged in a custody struggle for Assange's half-brother. His mother then took both children into hiding for the next five years. Assange moved several dozen times during his childhood, attending many schools, sometimes being home schooled.[2]

Hacking

In 1987, after turning 16, Assange began hacking under the name "Mendax" (derived from a phrase of Horace: "splendide mendax", or "nobly untruthful").[2] He and two other hackers joined to form a group which they named the International Subversives. Assange wrote down the early rules of the subculture: "Don’t damage computer systems you break into (including crashing them); don’t change the information in those systems (except for altering logs to cover your tracks); and share information".[2]

In response to the hacking, the Australian Federal Police raided his Melbourne home in 1991.[20] He was reported to have accessed computers belonging to an Australian university, the Canadian telecommunications company Nortel,[2] and other organisations, via modem.[21] In 1992, he pleaded guilty to 24 charges of hacking and was released on bond for good conduct after being fined AU$2100.[2][22] The prosecutor said "there is just no evidence that there was anything other than sort of intelligent inquisitiveness and the pleasure of being able to—what's the expression—surf through these various computers".[2]

Assange later commented, "It's a bit annoying, actually. Because I co-wrote a book about [being a hacker], there are documentaries about that, people talk about that a lot. They can cut and paste. But that was 20 years ago. It's very annoying to see modern day articles calling me a computer hacker. I'm not ashamed of it, I'm quite proud of it. But I understand the reason they suggest I'm a computer hacker now. There's a very specific reason."[8]

Child custody issues

In 1989, Assange started living with his girlfriend and they had a son, Daniel.[23] After they split up, they engaged in a lengthy custody struggle, and did not agree on a custody arrangement until 1999.[2][24] The entire process prompted Assange and his mother to form Parent Inquiry Into Child Protection, an activist group centered on creating a "central databank" for otherwise inaccessible legal records related to child custody issues in Australia.[24]

Computer programming and university studies

In 1993, Assange was involved in starting one of the first public internet service providers in Australia, Suburbia Public Access Network.[8][25] Starting in 1994, Assange lived in Melbourne as a programmer and a developer of free software.[22] In 1995, Assange wrote Strobe, the first free and open source port scanner.[26][27] He contributed several patches to the PostgreSQL project in 1996.[28][29] He helped to write the book Underground: Tales of Hacking, Madness and Obsession on the Electronic Frontier (1997), which credits him as a researcher and reports his history with International Subversives.[30][31] Starting around 1997, he co-invented the Rubberhose deniable encryption system, a cryptographic concept made into a software package for Linux designed to provide plausible deniability against rubber-hose cryptanalysis;[32] he originally intended the system to be used "as a tool for human rights workers who needed to protect sensitive data in the field."[33] Other free software that he has authored or co-authored includes the Usenet caching software NNTPCache[34] and Surfraw, a command-line interface for web-based search engines. In 1999, Assange registered the domain leaks.org; "But", he says, "then I didn't do anything with it."[35]

Assange has reportedly attended six universities at various times.[36] From 2003 to 2006, he studied physics and mathematics at the University of Melbourne. He has also studied philosophy and neuroscience.[36] He never graduated and received the minimum passing grades in most of his math courses.[2][37] On his personal web page, he described having represented his university at the Australian National Physics Competition around 2005.[2][38]

WikiLeaks

WikiLeaks was founded in 2006.[2][39] That year, Assange wrote two essays setting out the philosophy behind WikiLeaks: "To radically shift regime behavior we must think clearly and boldly for if we have learned anything, it is that regimes do not want to be changed. We must think beyond those who have gone before us and discover technological changes that embolden us with ways to act in which our forebears could not."[40][41][42] In his blog he wrote, "the more secretive or unjust an organisation is, the more leaks induce fear and paranoia in its leadership and planning coterie. ... Since unjust systems, by their nature induce opponents, and in many places barely have the upper hand, mass leaking leaves them exquisitely vulnerable to those who seek to replace them with more open forms of governance."[40][43]

Assange sits on Wikileaks's nine-member advisory board,[44] and is a prominent media spokesman on its behalf. While newspapers have described him as a "director"[45] or "founder"[20] of Wikileaks, Assange has said, "I don't call myself a founder";[46] he does describe himself as the editor in chief of WikiLeaks,[47] and has stated that he has the final decision in the process of vetting documents submitted to the site.[48] Like all others working for the site, Assange is an unpaid volunteer.[46][49][50][51][52] Assange says that Wikileaks has released more classified documents than the rest of the world press combined: "That's not something I say as a way of saying how successful we are – rather, that shows you the parlous state of the rest of the media. How is it that a team of five people has managed to release to the public more suppressed information, at that level, than the rest of the world press combined? It's disgraceful."[39] Assange advocates a "transparent" and "scientific" approach to journalism, saying that "you can't publish a paper on physics without the full experimental data and results; that should be the standard in journalism."[53][54] In 2006, CounterPunch called him "Australia's most infamous former computer hacker."[55] The Age has called him "one of the most intriguing people in the world" and "internet's freedom fighter."[35] Assange has called himself "extremely cynical".[35] The Personal Democracy Forum said that as a teenager he was "Australia's most famous ethical computer hacker."[36] He has been described as being largely self-taught and widely read on science and mathematics,[22] and as thriving on intellectual battle.[56]

WikiLeaks has been involved in the publication of material documenting extrajudicial killings in Kenya, a report of toxic waste dumping on the African coast, Church of Scientology manuals, Guantanamo Bay procedures, the 12 July 2007 Baghdad airstrike video, and material involving large banks such as Kaupthing and Julius Baer among other documents.[11]

When asked about the ideology and intended purpose of Wikileaks at the 2010 Oslo Freedom Forum, Assange stated:[57]

Our goal is to have a just civilization. That is sort of a personal motivating goal. And the message is transparency. It is important not to confuse the message with the goal. Nonetheless we believe that it is an excellent message. Gaining justice with transparency. It is a good way of doing that, it is also a good way of not making too many mistakes. We have a trans-political ideology, it is not right it is not left it is about understanding. Before you can give any advice, any program about how to deal with the world, how to put the civil into civilization. How to gain influence on people. Before you can have that program, first you have to understand what is actually going on.... And therefore any program or recommendation, any political ideology that comes out of that misunderstanding will itself be a misunderstanding. So, we say, to some degree all political ideologies are currently bankrupt. Because they do not have the raw ingredient they need to address the world. The raw ingredient to understand what is actually happening.

Public appearances

In addition to exercising great authority and editorial control within WikiLeaks, Assange acts as its public face. He has appeared at media conferences such as New Media Days '09 in Copenhagen,[58] the 2010 Logan Symposium in Investigative Reporting at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism,[59] and at hacker conferences, notably the 25th and 26th Chaos Communication Congress.[60] In the first half of 2010, he appeared on Al Jazeera English, MSNBC, Democracy Now!, RT, and The Colbert Report to discuss the release of the Baghdad airstrike video by Wikileaks. On 3 June he appeared via videoconferencing at the Personal Democracy Forum conference with Daniel Ellsberg.[61][62] Ellsberg told MSNBC "the explanation he [Assange] used" for not appearing in person in the USA was that "it was not safe for him to come to this country."[63] On 11 June he was to appear on a Showcase Panel at the Investigative Reporters and Editors conference in Las Vegas,[64] but there are reports that he cancelled several days prior.[65] On 10 June 2010, it was reported that Pentagon officials are trying to determine his whereabouts.[66][67] Based on this, there have been reports that U.S. officials want to apprehend Assange.[68] Ellsberg said that the arrest of Bradley Manning and subsequent speculation by US officials about what Assange may be about to publish "puts his well-being, his physical life, in some danger now."[63] In The Atlantic, Marc Ambinder called Ellsberg's concerns "ridiculous", and said that "Assange's tendency to believe that he is one step away from being thrown into a black hole hinders, and to some extent discredits, his work."[69] In Salon.com, Glenn Greenwald questioned "screeching media reports" that there was a "manhunt" on Assange underway, arguing that they were only based on comments by "anonymous government officials" and might even serve a campaign by the U.S. government, by intimidating possible whistleblowers.[70]

On 21 June 2010, Assange took part at a hearing in Brussels, Belgium, appearing in public for the first time in nearly a month.[71] He was a member on a panel that discussed Internet censorship and expressed his worries over the recent filtering in countries such as Australia. He also talked about secret gag orders preventing newspapers from publishing information about specific subjects and even divulging the fact that they are being gagged. Using an example involving The Guardian, he also explained how newspapers are altering their online archives sometimes by removing entire articles.[72][73] He told The Guardian that he does not fear for his safety but is on permanent alert and will avoid travel to America, saying "[U.S.] public statements have all been reasonable. But some statements made in private are a bit more questionable." He said "politically it would be a great error for them to act. I feel perfectly safe but I have been advised by my lawyers not to travel to the U.S. during this period."[71]

On 17 July, Jacob Appelbaum spoke on behalf of WikiLeaks at the 2010 Hackers on Planet Earth (HOPE) conference in New York City, replacing Assange due to the presence of federal agents at the conference.[74][75] He announced that the WikiLeaks submission system was again up and running, after it had been temporarily suspended.[74][76] Assange was a surprise speaker at a TED conference on 19 July 2010 in Oxford, and confirmed that WikiLeaks was now accepting submissions again.[77][78][79] On 26 July, after the release of the Afghan War Diary, Assange appeared at the Frontline Club for a press conference.[80]

Release of US diplomatic cables

On 28 November 2010, WikiLeaks began releasing some of the 251,000 American diplomatic cables in their possession, of which over 53 percent are listed as unclassified, 40 percent are "Confidential" and just over six percent are classified "Secret". The following day, the Attorney-General of Australia, Robert McClelland, told the press that Australia would inquire into Assange's activities and WikiLeaks.[81] He said that "from Australia's point of view, we think there are potentially a number of criminal laws that could have been breached by the release of this information. The Australian Federal Police are looking at that".[82] McClelland would not rule out the possibility that Australian authorities will cancel Assange's passport, and warned him that he might face charges should he return to Australia.[83] As of 11 December 2010 only 1295 cables have been released, or 1/2 of 1 percent of the total.[84][85]

The United States Department of Justice launched a criminal investigation related to the leak. US prosecutors are reportedly considering charges against Assange under several laws, but any prosecution would be difficult.[86] In a Time interview conducted after the release of the cables, Richard Stengel asked Assange whether Hillary Clinton should resign; he responded by stating, "She should resign if it can be shown that she was responsible for ordering US diplomatic figures to engage in espionage in the United Nations, in violation of the international covenants to which the US has signed up".[87]

Pentagon Papers whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg said that Assange "is serving our [American] democracy and serving our rule of law precisely by challenging the secrecy regulations, which are not laws in most cases, in this country." On the issue of national security considerations for the US, Ellsberg added that "He's obviously a very competent guy in many ways. I think his instincts are that most of this material deserves to be out. We are arguing over a very small fragment that doesn’t. He has not yet put out anything that hurt anybody's national security".[88] Assange told London reporters that the leaked cables showed US ambassadors around the world were ordered "to engage in espionage behavior" which he said seemed to be "representative of a gradual shift to a lack of rule of law in US institutions that needs to be exposed and that we have been exposing." [89]

Role as a publisher

Assange received the 2009 Media award from Amnesty International,[6] which are intended to "recognise excellence in human rights journalism"[90] and he has been recognized as a journalist by the Centre for investigative journalism.[5] In December 2010, US State Department spokesman Philip J. Crowley objected to the description of Assange as a journalist,[91] and also stated that the US State Department does not regard WikiLeaks as a media organization. In response to a question from the press, Crowley said; "I think he’s an anarchist, but he’s not a journalist."[92] Alex Massie wrote an article in The Spectator called "Yes, Julian Assange is a journalist", but acknowledged that "newsman" might be a better description of Assange.[7] Assange has said that he has been publishing factual material since age 25, and that it is not necessary to debate whether or not he is a journalist. He has stated that his role is "primarily that of a publisher and editor-in-chief who organises and directs other journalists".[93]

Alleged sex offences

On 20 August 2010, an investigation was opened against Assange and an arrest warrant issued in Sweden in connection with sexual encounters with two women, aged 26 and 31,[94] one in Enköping and the other in Stockholm.[95][96] Shortly after the investigation opened, chief prosecutor Eva Finné withdrew the warrant to arrest Assange, overruling the prosecutor who had been on call when the report had been filed and saying "I don't think there is reason to suspect that he has committed rape."[97] Assange denied the allegations, said he had consensual sexual encounters with the two women, and said along with his supporters that they were an attempt at character assassination and smear campaign.[98][99] He was questioned by police for an hour on 31 August,[100] and on 1 September a senior Swedish prosecutor, Marianne Ny, re-opened the investigation citing new information. The women's lawyer, Claes Borgström, a Swedish politician, had earlier appealed against the decision not to proceed.[101] Assange has said that the accusation against him is a "set-up" arranged by the enemies of WikiLeaks.[102]

In late October, Sweden denied Assange's application for a Swedish residency and work permit. On 4 November, Assange said that he was considering a formal request for political asylum in Switzerland as "a real possibility."[102] On 18 November, Stockholm District Court approved a request to detain Assange for questioning.[103][104][105] On 20 November, Sweden's National Criminal Police force issued an international arrest warrant for Assange via Interpol; an European Arrest Warrant was issued through the Schengen Information System.[106][107]

On 30 November 2010, Interpol issued a red notice against Assange on behalf of Sweden for questioning on allegations of "sex crimes", at Sweden's request.[108][109] Although the basis for Sweden's request included molestation, and unlawful coercion, Assange and some media accounts say that the dispute arose from incidents of consensual but unprotected sex.[110][111] A lawyer, however, accused Assange of having unprotected sex with a woman who was asleep. A lawyer for Assange said "It is highly irregular and unusual for the Swedish authorities to issue a red notice in the teeth of the undisputed fact that Mr Assange has agreed to meet voluntarily to answer the prosecutor's questions" outside Sweden[112] and also said Assange would fight extradition attempts[113] due to the possibility that it could lead to the Swedish handing him over to the United States.[114]

Assange was arrested in London by the Metropolitan Police Service on 7 December by appointment, after a voluntary meeting with the police.[15] Later that day, Assange was refused bail and held in custody on remand.[115] On 14 December Assange was granted bail with conditions including a £240,000 guarantee and surrender of his passport, but remained in custody due to appeal of the bail decision by Swedish prosecutors.[116] On 16 December, the appeal was dismissed, Assange was granted bail and he was placed under house arrest.[89] He is to serve his bail at Ellingham Hall in Norfolk and to observe a curfew. He will also have to report every day to a police station although being tagged by an electronic device.[117]

One of Assange's lawyers, Mark Stephens, has compared the legal proceedings to a show trial.[118] Assange's defense team also includes human rights lawyers Geoffrey Robertson QC[119] and solicitor Jennifer Robinson.[120]

Some observers believe that the sex charges against Assange may have been fabricated as part of a Central Intelligence Agency plot to either discredit Assange or to extradite him to the U.S. to face [[[espionage]] charges.[121][122][123][124]

Support and praise

Brazilian President, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, expressed his "solidarity" with Assange following Assange's 2010 arrest in the United Kingdom.[125][126] He further criticised the arrest of Assange as "an attack on freedom of expression".[127]

A source within the office of Russian President, Dmitry Medvedev, said that "Public and non-governmental organisations should think of how to help him." The comments followed commentary by Russian ambassador to NATO, Dmitry Rogozin, who stated that Julian Assange's earlier arrest on Swedish charges demonstrated that there was "no media freedom" in the west.[128]

In December 2010, the United Nations' Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Opinion and Expression, Frank LaRue, said Assange or other WikiLeaks staff should not face legal accountability for any information they disseminated, noting that "if there is a responsibility by leaking information it is of, exclusively of the person that made the leak and not of the media that publish it. And this is the way that transparency works and that corruption has been confronted in many cases."[129]

On 10 December 2010 over five hundred people rallied outside Sydney Town Hall and about three hundred fifty people gathered in Brisbane.[130] On 11 December 2010, more than one hundred people demonstrated at the British Embassy in Madrid to protest the arrest of Assange.[131]

Awards

Assange was the winner of the 2009 Amnesty International Media Award (New Media),[132] awarded for exposing extrajudicial assassinations in Kenya with the investigation The Cry of Blood – Extra Judicial Killings and Disappearances.[133] In accepting the award, he said: "It is a reflection of the courage and strength of Kenyan civil society that this injustice was documented. Through the tremendous work of organisations such as the Oscar foundation, the KNHCR, Mars Group Kenya and others we had the primary support we needed to expose these murders to the world."[134] He also won the 2008 Economist Index on Censorship Award.[5]

Assange was awarded the 2010 Sam Adams Award by the Sam Adams Associates for Integrity in Intelligence.[135][136] In September 2010, Assange was voted as number 23 among the "The World's 50 Most Influential Figures 2010" by the British magazine New Statesman.[137] In their November/December issue, Utne Reader magazine named Assange as one of the "25 Visionaries Who Are Changing Your World".[138] In December 2010, Julian Assange was named the Readers' Choice for Time magazine's 2010 Person of the Year,[14] as well as runner-up for 2010 Person of the Year.[139]

Criticism of US diplomatic cable leaks

Daniel Yates, a former British military intelligence officer, wrote that "Assange has seriously endangered the lives of Afghan civilians ... The logs contain detailed personal information regarding Afghan civilians who have approached NATO soldiers with information. It is inevitable that the Taliban will now seek violent retribution on those who have co-operated with NATO. Their families and tribes will also be in danger."[140] Responding to a critical letter from a White House spokesman, Assange said in August 2010 that 15,000 documents are still being reviewed "line by line" and that the names of "innocent parties who are under reasonable threat" would be removed.[141] Assange replied to the request[clarification needed] through Eric Schmitt, a New York Times editor. This reply was Assange's offer to the White House to vet any harmful documents; Schmitt responded that "I certainly didn't consider this a serious and realistic offer to the White House to vet any of the documents before they were to be posted, and I think it's ridiculous that Assange is portraying it that way now."[142]

Chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, Mike Mullen, said that "Mr. Assange can say whatever he likes about the greater good he thinks he and his source are doing, but the truth is, they might already have on their hands the blood of some young soldier or that of an Afghan family." Assange denies this has happened, and responded by saying, "...it’s really quite fantastic that [Robert] Gates and Mullen...who have ordered assassinations every day, are trying to bring people on board to look at a speculative understanding of whether we might have blood on our hands. These two men arguably are wading in the blood from those wars."[143]

A number of commentators, including current and former US government officials, have accused Assange of terrorism. Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell has called Assange "a high-tech terrorist",[144] and this view was mirrored by former US House speaker Newt Gingrich, who has been quoted as saying that "Information terrorism, which leads to people getting killed, is terrorism, and Julian Assange is engaged in terrorism. He should be treated as an enemy combatant."[145] Within the media, an editorial in the Washington Times by Jeffrey T. Kuhner said Assange should be treated "the same way as other high-value terrorist targets";[146][147] Fox News' National Security Analyst and host "K.T." McFarland has called Assange a terrorist, WikiLeaks "a terrorist organization" and has called for Bradley Manning's execution if he is found guilty of making the leaks;[148] and former Nixon aide and talk radio host G. Gordon Liddy has reportedly suggested that Assange's name be added to the "kill list" of terrorists who can be assassinated without a trial.[149]

Tom Flanagan, former campaign manager for Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper, commented in November 2010 that he thought Julian Assange should be assassinated. A complaint has been filed against Flanagan, which states that Flanagan "counselled and/or incited the assassination of Julian Assange contrary to the Criminal Code of Canada," in his remarks on the CBC programme Power & Politics.[150] Flanagan has since apologised for the remarks made during the programme and claimed his intentions were never "to advocate or propose the assassination of Mr. Assange".[151]

Residency

Though an Australian citizen, Assange has been profiled as not having a permanent address.[9] Assange has said he is constantly on the move. He has lived for periods in Australia, Kenya and Tanzania, and began renting a house in Iceland on 30 March 2010, from which he and other activists, including Birgitta Jónsdóttir, worked on the 'Collateral Murder' video.[2]

For much of 2010, he was visiting the United Kingdom, Iceland, Sweden and other European countries. On 4 November 2010, Assange told Swiss public television TSR that he was seriously considering seeking political asylum in neutral Switzerland and moving the operation of the WikiLeaks foundation there.[152]

In late November 2010, Deputy Foreign Minister Kintto Lucas of Ecuador appeared to be offering Assange residency with "no conditions... so he can freely present the information he possesses and all the documentation, not just over the Internet but in a variety of public forums".[153] Lucas believed that Ecuador may benefit from initiating a dialogue with Assange.[154] Foreign Minister Ricardo Patino stated on 30 November that the residency application would "have to be studied from the legal and diplomatic perspective".[155] A few hours later, President Rafael Correa stated that WikiLeaks "committed an error by breaking the laws of the United States and leaking this type of information... no official offer was [ever] made."[156][157] Correa noted that Lucas was speaking "on his own behalf"; additionally, he will launch an investigation into possible ramifications Ecuador would suffer from the release of the cables.[157]

In a hearing at the City of Westminster Magistrates' Court on 7 December 2010, Assange identified a post office box as his address. When told by the judge that this information was not acceptable, Assange submitted "Parkville, Victoria, Australia" on a sheet of paper. His lack of permanent address and nomadic lifestyle were cited by the judge as factors in denying bail.[158] He was ultimately released on bail, in part because journalist Vaughan Smith offered to provide Assange with an address for bail during the extradition proceedings, at his Norfolk mansion, Ellingham Hall.[159] Smith said the large estate would afford Assange some privacy because "it's quite hard to get too close without trespassing."[89]

References

- ^ "Julian Assange's mother recalls Magnetic". Australia: Magnetic Times. 7 August 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Khatchadourian, Raffi (7 June 2010). "No Secrets: Julian Assange's Mission for Total Transparency". The New Yorker. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ "ASSANGE, Julian Paul" (Document). Interpol. 30 November 2010.

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|archivedate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|archiveurl=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Johns-Wickberg, Nick (17 September 2010). "Daniel Assange: I never thought WikiLeaks would succeed". Crikey.

- ^ a b c "Julian Assange". Centre for investigative journalism. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ a b "Amnesty announces Media Awards 2009 winners". Amnesty International. 2 June 2009. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ a b Alex Massie (2 November 2010). "Yes, Julian Assange Is A Journalist". The Spectator. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ a b c Greenberg, Andy. "An Interview With WikiLeaks' Julian Assange — Andy Greenberg – The Firewall". blogs.forbes.com. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ a b Harrell, Eben (27 July 2010). "Defending the Leaks: Q&A with WikiLeaks' Julian Assange". TIME. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ^ "Profile: Julian Assange, the man behind Wikileaks". The Sunday Times. UK. 11 April 2010. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ^ a b "WikiLeak And Apache Attack In Iraq — Julian Assange". The Sydney Morning Herald. 9 April 2010. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ "WikiLeaks cables: Live Q&A with Julian Assange". The Guardian. 3 December 2010. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ "Russia official: WikiLeaks founder should get Nobel Prize". Haaretz. 8 December 2010.

- ^ a b Freidman, Megan (13 December 2010). "Julian Assange: Readers' Choice for TIME's Person of the Year 2010". Time Inc. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ a b "Wikileaks founder Julian Assange arrested in London". BBC. 7 December 2010. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- ^ http://www.abc.net.au/am/content/2010/s3095541.htm

- ^ http://www.abc.net.au/am/content/2010/s3095541.htm

- ^ "Courier Mail newspaper: Wikileaks founder Julian Assange a born and bred Queenslander". Couriermail.com.au. 29 July 2010. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- ^ a b "The secret life of Julian Assange". CNN. 2 December 2010. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ^ a b Guilliatt, Richard (30 May 2009). "Rudd Government blacklist hacker monitors police". The Australian. Retrieved 16 June 2010. [lead-in to a longer article in that day's The Weekend Australian Magazine]

- ^ Weinberger, Sharon (7 April 2010). "Who Is Behind WikiLeaks?". AOL. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ a b c Lagan, Bernard (10 April 2010). "International man of mystery". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ Nick Johns-Wickberg. "Daniel Assange: I never thought WikiLeaks would succeed". Crikey. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ a b Amory, Edward Heathcoat (27 July 2010). "Paranoid, anarchic... is WikiLeaks boss a force for good or chaos?". Daily Mail. Retrieved 27 October 2010.

- ^ "Suburbia Public Access Network". Suburbia.org.au. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- ^ Assange stated, "In this limited application strobe is said to be faster and more flexible than ISS2.1 (an expensive, but verbose security checker by Christopher Klaus) or PingWare (also commercial, and even more expensive)." See Strobe v1.01: Super Optimised TCP port surveyor

- ^ "strobe-1.06: A super optimised TCP port surveyor". The Porting And Archive Centre for HP-UX. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ "PostgreSQL contributors". Postgresql.org. Retrieved 29 November 2010.

- ^ "PostgreSQL commits". Git.postgresql.org. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ Annabel Symington (1 September 2009). "Exposed: Wikileaks' secrets". Wired Magazine. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- ^ Dreyfus, Suelette (1997). Underground: Tales of Hacking, Madness and Obsession on the Electronic Frontier. ISBN 1-86330-595-5.

- ^ Singel, Ryan (3 July 2008). "Immune to Critics, Secret-Spilling Wikileaks Plans to Save Journalism ... and the World". Wired. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ Dreyfus, Suelette. "The Idiot Savants' Guide to Rubberhose". Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ "NNTPCache: Authors". Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ a b c Barrowclough, Nikki (22 May 2010). "Keeper of secrets". The Age. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ a b c "PdF Conference 2010: Speakers". Personal Democracy Forum. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ Rosenthal, John (12 December 2010). "Mythbusted: Professor says WikiLeaks founder was 'no star' mathematician'". The Daily Caller. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

Assange, Julian (12 July 2006). "The cream of Australian Physics". IQ.ORG. Archived from the original on 20 October 2007.

A year before, also at ANU, I represented my university at the Australian National Physics Competition. At the prize ceremony, the head of ANU physics, motioned to us and said, 'You are the cream of Australian physics'.

- ^ a b "The secret life of Wikileaks founder Julian Assange". The Sydney Morning Herald. 22 May 2010. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ a b Andy Whelan and Sharon Churcher (1 August 2010). "FBI question WikiLeaks mother at Welsh home: Agents interrogate 'distressed' woman, then search her son's bedroom". Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ^ Assange, Julian (10 November 2006). "State and Terrorist Conspiracies" (PDF). Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ^ Assange, Julian (3 December 2006). "Conspiracy as Governance" (PDF). Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ^ "The non linear effects of leaks on unjust systems of governance". 31 December 2006. Archived from the original on 2 October 2007.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 20 October 2007 suggested (help) - ^ "WikiLeaks:Advisory Board". Wikileaks. Retrieved 16 June 2010. [dead link]

- ^ McGreal, Chris (5 April 2010). "Wikileaks reveals video showing US air crew shooting down Iraqi civilians". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ a b Interview with Julian Assange, spokesperson of WikiLeaks: Leak-o-nomy: The Economy of WikiLeaks

- ^ "Julian Assange: Why the World Needs WikiLeaks". Huffington Post. 19 July 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ Kushner, David (6 April 2010). "Inside WikiLeaks' Leak Factory". Mother Jones. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ WikiLeaks:Advisory Board – Julian Assange, investigative journalist, programmer and activist[dead link] (short biography on the Wikileaks home page)

- ^ Harrell, Eben, (26 July 2010) 2-Min. Bio WikiLeaks Founder Julian Assange 26 July 2010 Time.

- ^ Rumored Manhunt for Wikileaks Founder and Arrest of Alleged Leaker of Video Showing Iraq Killings – video report by Democracy Now!

- ^ Adheesha Sarkar (10 August 2010). "The People'S Spy". Telegraphindia.com. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "'A real free press for the first time in history': WikiLeaks editor speaks out in London". Blogs.journalism.co.uk. 12 July 2010. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ "Julian Assange: the hacker who created WikiLeaks". Csmonitor.com. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ Julian Assange: The Anti-Nuclear WANK Worm. The Curious Origins of Political Hacktivism CounterPunch, 25 November/ 26 2006 Cite error: The named reference "wankworm" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Julian Assange, monk of the online age who thrives on intellectual battle 1 August 2010

- ^ Lysglimt, Hans (9 December 2010). "Transcript of interview with Julian Assange (2010-4-26)". Oslo Freedom Forum. Farmann Magazine. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- ^ "The Subtle Roar of Online Whistle-Blowing". New Media Days. 19 November 2009. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- ^ Video of Julian Assange on the panel at the 2010 Logan Symposium, 18 April 2010

- ^ "25C3: Wikileaks". Events.ccc.de. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ "PdF Conference 2010 | June 3–4 | New York City | Personal Democracy Forum". Personaldemocracy.com. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ Hendler, Clint (3 June 2010). "Ellsberg and Assange". Columbia Journalism Review. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ a b Hamsher, Jane (11 June 2010). "Transcript: Daniel Ellsberg Says He Fears US Might Assassinate Wikileaks Founder". Firedoglake. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ "Showcase Panels". data.nicar.org. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ Poulsen, Kevin; Zetter, Kim (11 June 2010). "Wikileaks Commissions Lawyers to Defend Alleged Army Source". Wired. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^

McGreal, Chris (11 June 2010). "Pentagon hunts WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange in bid to gag website". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Text "Media" ignored (help); Text "The Guardian" ignored (help) - ^ Shenon, Philip (10 June 2010). "Wikileaks Founder Julian Assange Hunted by Pentagon Over Massive Leak". Pentagon Manhunt. The Daily Beast. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ^ Taylor, Jerome (12 June 2010). "Pentagon rushes to block release of classified files on Wikileaks". The Independent. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ Ambinder, Marc. "Does Julian Assange Have Reason to Fear the U.S. Government?". The Atlantic.

- ^

Greenwald, Glenn (18 June 2010). "The strange and consequential case of Bradley Manning, Adrian Lamo and WikiLeaks". Salon Media Group (Salon.com). Retrieved 16 December 2010.

On 10 June, former New York Times reporter Philip Shenon, writing in The Daily Beast, gave voice to anonymous "American officials" to announce that "Pentagon investigators" were trying "to determine the whereabouts of the Australian-born founder of the secretive website Wikileaks [Julian Assange] for fear that he may be about to publish a huge cache of classified State Department cables that, if made public, could do serious damage to national security." Some news outlets used that report to declare that there was a "Pentagon manhunt" underway for Assange – as though he's some sort of dangerous fugitive.

- ^ a b "Wikileaks founder Julian Assange emerges from hiding". The Daily Telegraph. 22 June 2010. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ "Hearing: (Self) Censorship New Challenges for Freedom of Expression in Europe". Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe. Retrieved 2 June 2010.[dead link]

- ^ Traynor, Ian (21 June 2010). "WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange breaks cover but will avoid America". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- ^ a b Singel, Ryan (19 July 2010). "Wikileaks Reopens for Leakers". Wired. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ McCullagh, Declan (16 July 2010). "Feds look for Wikileaks founder at NYC hacker event". News.cnet.com. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ Jacob Appelbaum, WikiLeaks keynote: 2010 Hackers on Planet Earth conference, New York City, 17 July 2010

- ^ "Surprise speaker at TEDGlobal: Julian Assange in Session 12". Blog.ted.com. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ "Julian Assange: Why the world needs WikiLeaks". Ted.com. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ "Julian Assange – TED Talk – Wikileaks". Geekosystem. 19 July 2010. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ "Frontline Club 07/26/10 04:31 am". Ustream.tv. 26 July 2010. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ "Australia opens WikiLeaks inquiry". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ^ "Doorstop on leaking of US classified documents by Wikileaks". Attorney-General for Australia. 29 November 2010. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ^ "Australia warns Assange of possible charges if he returns to Australia". Monstersandcritics.com. 17 November 2010. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ^ "Secret US Embassy Cables", Wikileaks. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- ^ Greenwald, Glenn (10 December 2010). "The media's authoritarianism and WikiLeaks". Salon Media Group (Salon.com). Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ Savage, Charlie (7 December 2010). "U.S. Prosecutors Study WikiLeaks Prosecution". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ Chua, Howard. "WikiLeaks Founder Assange to TIME: Clinton 'Should Resign'". TIME. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ^ Jacobs, Samuel P. (11 June 2010). "Daniel Ellsberg: Wikileaks' Julian Assange "in Danger"". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ a b c "UK court upholds bail for WikiLeaks' Assange". Thomson Reuters. 16 December 2010. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ "AIUK: Media Awards". Amnesty.org.uk. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- ^ Wikileaks founder Julian Assange 'anarchist', not journalist, The Indian Express, 3 December 2010.

- ^ Philip J. Crowley, Assistant Secretary, 2 December 2010 Daily Press Briefing, Washington, DC

- ^ Julian Assange (3 December 2010). "Julian Assange answers your questions". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ TNN (21 August 2010). "Sex accusers boasted about their 'conquest' of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange". Timesofindia.indiatimes.com. The Times of India. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- ^ Cody, Edward (9 September 2010). "WikiLeaks stalled by Swedish inquiry into allegations of rape by founder Assange". The Washington Post. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- ^ "Swedish inquiry reopen investigations into allegations of sexual misconduct by founder Assange on third level of appeal". Anklagermyndigheten. 10 September 2010. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- ^ "Swedish rape warrant for Wikileaks' Assange cancelle". BBC.

- ^ Davies, Caroline (22 August 2010). "WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange denies rape allegations". The Guardian.

- ^ David Leigh, Luke Harding, Afua Hirsch and Ewen MacAskill. "WikiLeaks: Interpol issues wanted notice for Julian Assange". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange questioned by police". The Guardian. 31 August 2010.

- ^ "Sweden reopens investigation into rape claim against Julian Assange". The Guardian. 10 September 2010.

- ^ a b "Wikileaks founder may seek Swiss asylum: interview". The Sydney Morning Herald. 5 November 2010. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ Karl Ritter, Malin Rising (18 November 2010). "Sweden to issue int'l warrant for Assange". Msnbc.com. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- ^ Wikileaks Assange's detention order upheld by Sweden. BBC

- ^ "WikiLeaks to drop another bombshell". The Sydney Morning Herald. 23 November 2010. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ^ "Warrant for WikiLeaks founder condemned". Ft.com. 22 November 2010. Retrieved 29 November 2010.

- ^ "Assange hits back at rape allegations". Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ "Wikileaks' Assange appeals over Sweden arrest warrant". BBC News. 1 December 2010. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ^ Interpol (14 May 2010). "Enhancing global status of INTERPOL Red Notices focus of high level meeting". Interpol.int. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ^ Dylan Welch (3 December 2010). "Timing of sex case sparks claims of political influence". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ Raphael Satter and Malin Rising (2 November 2010). "The noose tightens around WikiLeaks' Assange". Associated Press. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ Townsend, Mark (1 December 2010). "British police seek Julian Assange over rape claims". Guardian. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ "Wikileaks' Julian Assange to fight Swedish allegations". BBC. 5 December 2010. Retrieved 5 December 2010.

- ^ Sam Jones and agencies (5 December 2010). "Julian Assange's lawyers say they are being watched". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 December 2010.

- ^ Vinograd, Cassandra; Satter, Raphael G. (7 December 2010). "Judge Denies WikiLeaks Founder Julian Assange Bail". The Associated Press. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- ^ "Wikileaks founder Assange bailed, but release delayed". BBC. 8 December 2010. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ "Assange walks free after nine days in jail". The Guardian. 17 December 2010.

- ^ "Sweden challenges Julian Assange bail decision - RTÉ News". Rte.ie. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ "Geoffrey Robertson to defend Assange". Theage.com.au. 8 December 2010. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ "Assange moved to prison's segregation unit". Google.com. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ Christopher Beam (9 December 2010). "The Spy Who Said She Loved Me". Slate.

- ^ "The 'honeytrap' that snared Assange". Dailybhaskar.in. 9 December 2010.

- ^ Tom Hayden (15 December 2010). "Swedish State on Trial in Assange Case?". The Nation.

- ^ Richard Pendlebury (7 December 2010). "The Wikileaks sex files: How two one-night stands sparked a worldwide hunt for Julian Assange". Daily Mail - MailOnline.

- ^ Antonova, Maria (9 December 2010). "Putin leads backlash over WikiLeaks boss detention". Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney Moring Herald. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ "President Lula Shows Support for Wikileaks (video available)". 9 December 2010.

- ^ "Wikileaks: Brazil President Lula backs Julian Assange". BBC News. 10 December 2010. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- ^ Harding, Luke (9 December 2010). "Julian Assange should be awarded Nobel peace prize, suggests Russia". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ Eleanor Hall (9 December 2010). "UN rapporteur says Assange shouldn't be prosecuted". abc.net.au. ABC Online. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ "''WikiLeaks supporters rally for Assange'', 10 December 2010". SBS. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ Associated, The. "Pro-WikiLeaks demonstrations held in Spain; planned for elsewhere in Europe, Latin America - Yahoo! News". Ca.news.yahoo.com. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ Nystedt, Dan (27 October 2009). "Wikileaks leader talks of courage and wrestling pigs". Computerworld. International Data Group. IDG News Service. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- ^ Report on Extra-Judicial Killings and Disappearances 1 March 2009

- ^ "WikiLeaks wins Amnesty International 2009 Media Award for exposing Extra judicial killings in Kenya".. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- ^ Murray, Craig (19 August 2010). "Julian Assange wins Sam Adams Award for Integrity". Retrieved 3 November 2010.

- ^ "WikiLeaks Press Conference on Release of Military Documents". cspan.org. Retrieved 3 November 2010.[dead link] This conference can be viewed by searching for wikileaks at cspan.org

- ^ "Julian Assange – 50 People Who Matter 2010". Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- ^ "Julian Assange: The Sunshine Kid". Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ Gellman, Barton (15 December 2010). "Runners-up: Julian Assange". Time Inc. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ Yates, Daniel (30 July 2010). "Leaked Afghan files 'put civilians at risk'". Channel 4 News. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- ^ "Sweden Withdraws Arrest Warrant for Embattled WikiLeaks Founder". .voanews.com. 20 August 2009. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "Informant says WikiLeaks suspect had civilian help". 1 August 2010. Retrieved 3 November 2010.

- ^ Amy Goodman (3 August 2010). "Julian Assange Responds to Increasing US Government Attacks on WikiLeaks". Democracy Now.

- ^ Tom Curry (5 December 2010). "McConnell optimistic on deals with Obama". msnbc.com.

- ^ Shane D'Aprile (5 December 2010). "Gingrich: Leaks show Obama administration 'shallow,' 'amateurish'". The Hill.

- ^ "Washington Times Editorial Suggests Killing Julian Assange". dcist. Retrieved 13 December 2010.

- ^ Jeffrey T. Kuhner (2 December 2010). "KUHNER: Assassinate Assange". The Washington Times.

- ^ KT McFarland (30 November 2010). "Yes, WikiLeaks Is a Terrorist Organization and the Time to Act Is NOW". Fox News.

- ^ Drew Zahn (1 December 2010). "G. Gordon Liddy: WikiLeaks chief deserves to be on 'kill list'". WorldNetDaily.

- ^ Barber, Mike (6 December 2010). "Heat's on Flanagan for 'inciting murder' of WikiLeaks founder; PM's ex-adviser subject of formal police complaint". Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ "Let Flanagan's remarks die – - Macleans OnCampus". Oncampus.macleans.ca. 4 December 2010. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ "WikiLeaks founder says may seek Swiss asylum". Reuters. 4 November 2010.

- ^ AFP 30 November 2010 (4 November 2010). "Ottawa Citizen online report of Ecuador offer of asylum to Assange". Ottawacitizen.com. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Horn, Leslie (1 January 1970). "WikiLeaks' Assange Offered Residency in Ecuador". Pcmag.com. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ^ "Ecuador alters refuge offer to WikiLeaks founder". The Washington Post. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ^ "Ecuador President Says No Offer To WikiLeaks Chief". Cbsnews.com. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ^ a b Bronstein, Hugh. "Ecuador backs off offer to WikiLeaks' Assange". Reuters.com. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ^ Maestro, Laura Perez (7 December 2010). "WikiLeaks' Assange jailed while court decides on extradition". CNN. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Norman, Joshua. "Just Where Is WikiLeaks Founder Julian Assange's "Mansion Arrest"? CBS News, 16 December 2010

External links

- Full coverage at Aljazeera

- Profile: Wikileaks founder Julian Assange at BBC News

- Full coverage at The Guardian

- Special report at Reuters

- Video profile on SBS Dateline

- Julian Assange: Hero or Villain? – slideshow by Life magazine

- "Meet the Aussie behind Wikileaks". Fairfax New Zealand. 8 July 2008.

- "WikiLeaks editor on Apache combat video: No excuse for US killing civilians". RussiaToday. April 2010.

- Archived versions of the home page on Julian Assange's web site iq.org (at the Internet Archive)

- "WikiLeaks Release 1.0: Insight into vision, motivation and innovation". 26th Chaos Communication Congress. 30 December 2009.

- Use dmy dates from December 2010

- Ill-formatted IPAc-en transclusions

- Wikipedia neutral point of view disputes from December 2010

- 1971 births

- Australian activists

- Australian computer programmers

- Australian Internet personalities

- Australian journalists

- Australian whistleblowers

- Internet activists

- Living people

- People from Townsville, Queensland

- University of Melbourne alumni

- WikiLeaks