Pashalik of Yanina: Difference between revisions

fix |

on identity |

||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

The principal role of geography in the communal groups of his time were comprehended by Ali. He insisted that Ioannina, located in the Greek [[Epirus (region)|district of Epirus]], was Albanian. He also considered the Albanian population who lived in the area not as immigrants but as indigenous people of the region. He tried to justify his plans on the territories under foreign protectorate on the Ionian coast also by insisting that they were part of "Albania" as well.{{sfn|Fleming|2014|p=63}} |

The principal role of geography in the communal groups of his time were comprehended by Ali. He insisted that Ioannina, located in the Greek [[Epirus (region)|district of Epirus]], was Albanian. He also considered the Albanian population who lived in the area not as immigrants but as indigenous people of the region. He tried to justify his plans on the territories under foreign protectorate on the Ionian coast also by insisting that they were part of "Albania" as well.{{sfn|Fleming|2014|p=63}} |

||

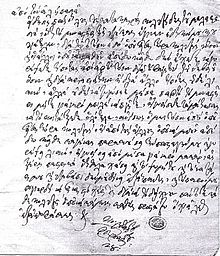

Language was a major definiting element in Ali's identity, as well of his government and the region it controlled in general. Diplomatic business was exclusively conducted in Greek as well as much of the former correspondence. The formal bureaucratic language of the Ottoman Emire was entirely replaced with Greek in the pashalik.{{sfn|Fleming|2014|p=63}} |

|||

== History == |

== History == |

||

Revision as of 02:51, 14 July 2023

Pashalik of Yanina | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1787–1822 | |||||||||||||

Greatest extent of the Pashalik of Yanina (in red) excluding the Morea Eyalet compared to the rest of Albanian pashaliks | |||||||||||||

| Status | Autonomous province of the Ottoman Empire, de facto independent[a] | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Yanina 39°40′N 20°51′E / 39.667°N 20.850°E | ||||||||||||

| Government | Pashalik | ||||||||||||

| Pasha | |||||||||||||

• 1787 – 1822 | Ali Pasha | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern period | ||||||||||||

• Established | 1787 | ||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1822 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

The Pashalik of Yanina, sometimes referred to as the Pashalik of Ioannina or Pashalik of Janina, was an autonomous pashalik within the Ottoman Empire between 1787 and 1822 covering large areas of Albania, Greece, and North Macedonia. The pashalik acquired a high degree of autonomy and even managed to stay de facto independent[a] under the Ottoman Albanian ruler Ali Pasha, though this was never officially recognized by the Ottoman Empire. Its core was the Ioannina Eyalet, centred on the city of Ioannina in Epirus. At its peak, Ali Pasha and his sons ruled over southern and central Albania, the majority of mainland Greece, including Epirus, Thessaly, West Macedonia, western Central Macedonia, Continental Greece (excluding Attica), and the Peloponnese, and parts of southwestern North Macedonia around Ohrid and Manastir.[b] Conceiving his territory in increasingly independent terms, Ali Pasha's correspondence and foreign Western correspondence frequently refer to the territories under Ali's control as Albania,[8] while his subject population was by vast majority Greek.[9]

Background

Ali Pasha first came to power as when he was appointed mutasarrıf of Ioanninna at the end of 1784 or beginning of 1785, but was soon dismissed, returning to the position only at the end of 1787 or the start of 1788.[11] Ali gained control of Delvina and became ruler of the Sanjak of Delvina in 1785, but did not have control full control of the Sanjak, with the regions of Himara (1797) and Gjirokastër (1811) being taken later. Additionally, the regions of Margariti and Paramythia, which fell within Sanjak of Delvina, and Fanari, within the Sanjak of Ioannina (conquered later by Ali), were ruled by Cham Albanian landlords, such as Hasan Çapari, who remained in conflict with Ali Pasha throughout much of the Pashalik's existence.[12]

In 1787 Ali Pasha took control of the Sanjak of Trikala (Thessaly), which was later officially rewarded to him for his support for the sultan's war against Austria. Shortly afterwards, in 1787 or 1788, he seized control of the town of Ioannina and declared himself ruler of the sanjak, which remained his power base for the next 34 years.[13] This marked the beginning of the Pashalik of Yanina, with Ali self-appointing himself Pasha of Yanina and delegating the title of Pasha of Trikala to his son, Veli.[14] At this point, the Sanjaks of Delvina, Trikala, and Yanina composed the Pashalik.[15]

Like other semi-independent regional leaders that emerged in that time, such as Osman Pazvantoğlu, he took advantage of a weak Ottoman government to expand his territory until he gained de facto control over much of Albania and mainland Greece, either directly or through his sons.[16]

The principal role of geography in the communal groups of his time were comprehended by Ali. He insisted that Ioannina, located in the Greek district of Epirus, was Albanian. He also considered the Albanian population who lived in the area not as immigrants but as indigenous people of the region. He tried to justify his plans on the territories under foreign protectorate on the Ionian coast also by insisting that they were part of "Albania" as well.[17]

Language was a major definiting element in Ali's identity, as well of his government and the region it controlled in general. Diplomatic business was exclusively conducted in Greek as well as much of the former correspondence. The formal bureaucratic language of the Ottoman Emire was entirely replaced with Greek in the pashalik.[17]

History

Russo-Turkish War (1787–1792)

Taking advantage of another Russo-Turkish War starting in 1787, Ali annexed the regions of Konitsa (in the Sanjak of Ioannina), and Libohovë, Përmet and Tepelenë (from the Sanjak of Avlona) to the Pashalik during the years 1789 to 1791. During this period, he also purchased Arta, giving the Pashalik access to the shores of the Ionian Sea via the Gulf of Arta. In 1789, the Aromanian town of Moscopole, within the Sanjak of Elbasan, was sacked and destroyed.[18][19] Also in 1789, Ali first invaded the semi-independent Souliote Confederacy to the west of the Sanjak of Ioannina, following their mobilisation of 2,200 Souliotes in March 1789 against the Pashalik and the Muslims of Rumelia.[20] A second campaign against the Souliotes took place in 1790. During these two campaigns, the Pashalik captured some Parasouli settlements, but ultimately was repulsed from the core Souli region.[21]

Starting in 1788, Ali had attempted to take control of the Sanjak of Karli-Eli, finally invading in October 1789. The Ottoman government reacted by granting the entire sanjak of Karli-Eli (minus the voevodalik of Missolonghi) as a personal hass to Mihrişah Valide Sultan, the mother of Sultan Selim III, which prevented Ali Pasha from annexing the territory. The Sanjak was eventually taken in 1806, following the death of Mihrişah the previous year.[22]

Continued war against Souli (1792–1793)

Following the end of the Russo-Turkish War in 1792, Ali ceased his expansions in order to avoid repercussions from Sultan Selim III. Additionally, his forces took part formally on the side of the Porte in a campaign against Shkodër in 1793.[14] Despite the conclusion of the Russo-Turkish War and the expansion of his territories, the Pashalik's defeat against the Souliotes resulted in Ali's obsession with capturing the Confederacy.[21] He launched another campaign in July 1792, dispatching 8,000-10,000 Albanians from the Pashalik to take the territory, with the Souliotes raising 1,300 men, but were defeated again. A peace agreement was made, with prisoners and hostages being exchanged and Parasouli villages captured in the previous two years being returned to the Souliotes.[23]

During the Yanina-Souli conflict, the Himariotes had supported the Souliotes. In revenge, Ali Pasha led a raid against the town of Himara in 1797, and more than 6,000 civilians were slaughtered.[24]

Alliance and War with France (1797–1780)

In 1797, France conquered Venice and gained from it control over the Ionian Islands and several coastal possessions in Epirus (Parga, Preveza, Vonitsa, Butrinto, and Igoumenitsa), making them neighbours to the Pashalik. In order to gain further access to the Ionian Sea, Ali formed an alliance with Napoleon I of France that same year, who had established Francois Pouqueville as his general consul in Yanina.[25] He received ammunition and military advisors from the French. However, shortly afterwards in 1798 the Ottoman Empire went to war with France following their invasion of Egypt. Ali Pasha responded by seizing the French coastal territories of Butrint and Igoumenitsa (added to the Sanjak of Delvina), Preveza (added to the Sanjak of Ioannina), and Vonitsa, with Parga remaining as the sole French possession in mainland Greece.[26] The French garrison in Preveza was destroyed in the Battle of Nicopolis, which was followed by a massacre. Following the capture of Preveza, Ali secured the neutrality of the Souliotes (who were dependent on French-controlled Preveza and Parga for livestock and ammunition supplies) through bribing of their leaders, which also caused internal conflict among the Souliote clans.[27] A combined Russian-Ottoman force captured the Ionian Islands during 1799–1780, resulting in the establishment of the Septinsular Republic.

Campaigns against Souli (1799–1803)

By 1799, the Pashalik was engaged in rivalry with the Pashalik of Berat to the north, which, like the Pashalik of Yanina, was also largely independent. Additionally, within the Pashalik there were several semi-independent regions that posed a threat to Ali Pasha's rule: the region of Delvina, in the north of Sanjak of Delvina; Chameria, in the south of Sanjak of Delvina and spilling into the Sanjak of Ioannina; and the Souliote Confederacy, to the west of the Sanjak of Ioannina. The Russians quickly sought to weaken the Pashalik's influence in the region, showing support for the aforementioned regions. Ali Pasha responded that same year by temporarily subduing the beys of three of the regions (Berat, Delvina, and Chameria).[28] He additionally annexed the neighbouring region Himara to the Sanjak of Delvina and established good relations with the Himariotes. He financed various public works and churches, and built a large church opposite of Porto Palermo Castle.

Following this, a campaign was launched against the Souliotes in Autumn 1799,[28] but this presumably failed. Another campaign was mounted in June–July 1800, with the Pashalik raising 11,500 men. However, a direct assault on the Souliote Confederacy failed, resulting in Ali besieging the core Souli villages by separating the Souli and Parasouli territories. For two years, the Souliotes were able to resist the siege by smuggling supplies from Parga, Paramythia, and Margariti. The Souliotes additionally requested aid from the Septinsular Republic, but Ali responded by threatening the Republic's possession of Parga.[29] Aid was later provided in secret in 1803. In April 1802, a French corvette in Parga supplied the Souliotes with food, weapons and ammunition, providing a pretext for a new campaign by Ali against the Souliotes.[30]

Following four years of conflict, in 1803 Ali Pasha raised Albanian forces from Epirus and Southern Albania for a final assault on the Souli Confederacy. At this point, the situation in Souli was dire due to a lack of supplies.[31] The Souliote War of 1803 resulted in the conquest of the entire Souliote territory and its incorporation into the Pashalik, with expulsions and atrocities against the Souliotes following.[28] Some Souliotes fled to Parga, but were forced to cross the sea into the Septinsular Republic in March 1804 after Ali threatened to attack the city.[32][33] Earlier, in November 1803, a treaty was signed between the Pashalik of Yanina and the Septinsular Republic.[34]

Conflict with Russia and France (1804–1809)

Anxious to expand its influence to the Greek mainland, Russia signed alliances with Himariot and Cham Albanian beys on 27 June 1804, who were rivals to Ali Pasha. Additionally, Russia mobilised Souliot refugees in the Septinsular Republic for an offensive against the Pashalik, but this was cut short when Ali Pasha learned of the Russian plans and an Ottoman naval squadron made an unexpected appearance off Corfu.[35]

Because of Ali Pasha's aggressive expansions, a rift formed between the Pashalik and the Ottoman Empire. As a result, Ali sought to ally himself to foreign European powers. In 1806, Ali again entered into an alliance with Napoleon I after being promised Corfu and its straits, and again became enemies with Russia at the start of another Russo-Turkish War in 1806. However, these promises were not fulfilled and so relations between the Pashalik and France later ended.[36]

In 1806, Ali sent forces under the command of his sons Veli Pasha and Muhtar Pasha to aid the Ottoman effort in defeating the First Serbian Uprising in the Sanjak of Smederevo. In 1813, the rebellion was crushed by the Ottoman army, mostly composed Bosnians, from the Pashalik of Bosnia, and Albanians, from the Pashaliks of Scutari and Yanina.

In 1807, following the entry of the Septinsular Republic (a nominally Ottoman vassal) into the latest Russo-Turkish War on the side of Russia, Ali sent forces under Veli Pasha to attack the Republic.[37] Lefkada was assaulted in Spring 1807, with the backing of Napoleon, and Santa Maura besieged, but the defenders, reinforced by Souliote and Russian forces, repelled the Pashalik's forces.[38][38]

After the Treaty of Tilsit in July 1807, Napoleon granted Alexander I, Emperor of Russia, his plan to dismantle the Ottoman Empire, and in exchange Russia ceded the Ionian Islands and Parga to France, reestablishing French rule. As a result, Ali allied himself with the British. His machinations were permitted by the Ottoman government in Constantinople from a mixture of expediency – it was deemed better to have Ali as a semi-ally than as an enemy – and weakness, as the central government did not have enough strength to oust him at that time.[citation needed]

Between 1807 and 1812, Veli ruled as Pasha of Morea, and at an unknown date Muhtar became Pasha of Inebahti, resulting in both regions being incorporated into the Pashalik.[39]

As relations with France deteriorated, Ali Pasha sought the capture of Parga, the last settlement in Epirus not under his control. In response, the French twice made plans to invade the Pashalik. The first, chronicled by Theodoros Kolokotronis, involved using the Albanian Regiment, supported by French artillery and Cham Albanians recruited by Ali Farmaki, to invade Morea, which at the time (around 1809) was part of the Pashalik under the rule of Veli Pasha. In his place they would install a mixed Christian-Muslim government, while the French mediated with the Porte to secure its approval. According to Kolokotronis, the plan was to be carried out in 1809, but was thwarted by the British occupation of French-held Zakynthos, Cephalonia, Kythira, and Ithaca that same year.[40][41]

The second attempt involved a detachment of 25 men of the Albanian Regiment, under Lt. Colonel Androutsis, who were sent to aid a Himariot revolt against Ali Pasha's forces in October 1810. Their ship foundered near Porto Palermo, however, and when attacked by Ali's forces, they were captured and taken prisoner to Ioannina.[43]

The poet George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron visited Ali's court in Tepelena and Yanina in 1809 and recorded the encounter in his work Childe Harold.[13] He evidently had mixed feelings about the despot, noting the splendour of Ali's court and some Orthodox cultural revival that he had encouraged in Yanina, which Byron described as being "superior in wealth, refinement and learning" to any other Albanian town. In a letter to his mother, however, Byron deplored Ali's cruelty: "His Highness is a remorseless tyrant, guilty of the most horrible cruelties, very brave, so good a general that they call him the Mahometan Buonaparte ... but as barbarous as he is successful, roasting rebels, etc.."[44]

War with Berat (1809)

In 1809, Ali Pasha invaded the Pashalik of Berat, ruled by fellow Albanian Pashalik, Ibrahim Pasha. Against the forces of Ibrahim Pasha and his brother Sephir Bey, ruler of Avlona, Ali sent Armatoles from Thessaly. After villages had been burnt, peasants robbed and hanged, and flocks carried off on both sides, peace was made. Ali married his sons Muhtar Pasha and Veli Pasha to Ibrahim's daughters, and the territories of the Pashalik of Berat passed to Muhtar as a dowry. Muhtar became governor of much of Central Albania and part of western Macedonia, resulting in a further expansion of the Pashalik of Yanina.[45][36][46] As Sephir bey had displayed qualities which might prove formidable hereafter, Ali contrived to have him poisoned by a physician; and, in his usual fashion, he hanged the agent of the crime, that no witness might remain of it.[45] Ali Pasha had designs to defeat the Pasha of Berat, become vizir of Epirus, fight with the Sultan, and take Constantinople.[47]

Consolidating power (1809–1820)

Despite French opposition, Ali seized control of the remainder of the Sanjak of Avlona in 1810, following the assassination of Sephir Bey. In 1811, the region of Delvina was reconquered, and the region of Gjirokastër annexed, resulting in the complete annexation of the Sanjak of Delvina. At this point, the Pashalik consisted of the entirety of Southern Albania, Epirus (excluding Parga), and Thessaly, as well as the majority of Central Albania and small parts of Macedonia, with all major regional rivals having been defeated. These expansions strengthened the autonomy of the region, however a lack of foreign support meant that the Pashalik was still dependent on the Ottoman Empire. The Pashalik was composed of an Albanian feudal class and army, with Ali's power being assured by the Greek majority. The population of the Pashalik itself was primarily Greek and Albanian.[36] Also as a result of persecution against local Sarakatsani and Aromanians several families that belonged to those communities were forced to migrate to regions outside Ali's rule.[48]

On 15 March 1812, Ali sent Greek troops under the command of Thanasis Vagias to destroy the Muslim Albanian village of Kardhiq, after his Muslim Albanian followers had refused to do so. This action was ordered in revenge for the rape of his mother and sister, which had occurred in Kardhiq. The village was destroyed and 730 of its inhabitants killed.[49][50][51]

In 1812 the settlement of Agia, belonging to Parga, was captured by Daut Bey, nephew of Ali Pasha. He then massacred and enslaved the local population. A siege of Parga ensued but failed, with Daut being killed during the siege.[52]

By 1815, the British had established full control of the French territories of the Ionian Islands and Parga, establishing the United States of the Ionian Islands. In 1819, the British sold the city of Parga to Ali Pasha (the subject of Francesco Hayez's later painting The Refugees of Parga), resulting in its annexation to the Sanjak of Delvina within the Pashalik. This decision was highly unpopular among the predominantly Greek and pro-Venetian population of Parga, who refused to become Muslim subjects and decided to abandon their homes. Along with the locals, Klepht and Souliote refugees in Parga fled to nearby Corfu.[53][54][55][56] Ali Pasha brought local Cham Albanians to repopulate Parga.[56]

Fall (1820–1822)

In 1820, Ali ordered the assassination of Gaskho Bey, a political opponent in Constantinople.[57] The reformist Sultan Mahmud II, who sought to restore the authority of the Sublime Porte, took this opportunity to move against Ali by ordering his deposition. Ali refused to resign his official posts and put up a formidable resistance to Ottoman troop movements, indirectly helping the Greek Independence as some 20,000 Turkish troops were fighting Ali's formidable army.[7]

On 4 December 1820, Ali Pasha's Albanian troops and the Souliotes formed an anti-Ottoman coalition, in which the Souliotes contributed 3,000 soldiers. Ali Pasha gained the support of the Souliotes by promising them the return of their lands, and in part by appealing based to shared Albanian origins.[58] Initially the coalition was successful and managed to control most of the region, but when the Muslim Albanian troops of Ali Pasha were informed of the beginning of the Greek revolts in the Morea they abandoned it.[59]

In January 1822 Ottoman agents assassinated Ali Pasha and sent his head to the Sultan.[13] After his death, the Pashalik was dissolved and replaced with the Ioannina Eyalet, composed of the Sanjaks of Ioannina, Avlona, Delvina, and Preveza. At its peak, the Pashalik controlled the regions of Elbasan, Ohrid, Görice, western Salonica, Avlona, Delvina, Ioannina, Trikala, Karli-Eli, Inebahti, Eğriboz, and Morea.[60] The coastal fortresses of Porto Palermo, Saranda, Butrint, Parga, Preveza, Plagia, and Nafpaktos were controlled by Ali Pasha.[61]

Economy

The territories of the Pashalik of Yanina have been characterized by a long period of international trade, mainly with Italy, and in particular with Ancona, Venice, Livorno, and Padua. Ioannina's trade was based on exporting both valueadded and crude goods and importing western luxury items.[62]

Ioannina's textile products had a wide trade distribution. Silk braid, blankets, scarves, gold and silver thread, and embroidered slippers and garments were among the main commercial products exported to Italy and sold throughout the Balkans.[63]

Crude goods were also widely exported from Ali Pasha's territory. There was a developed wood industry in the area, which also provided the resin that had a wide local trade. For a long period lumber from northern Epirus and southern Albania was exported from Ioannina to Toulon and used by the French for shipbuilding. The British gained control of the Ionian Islands in 1809; after then they became the major commercial partner of the region lumber trade was continued with the English. Ioannina exported fruits like lemons, oranges, and hazelnuts produced in Arta, but also olive oil, corn, and Albanian tobacco, the latter being particularly in demand for snuff. Albanian horses were sold and exported throughout the Balkans.[64]

Ioannina also operated as the hub for the distribution of many imports from different European regions, which were brought to the capital of the Pashalik on horseback from eastern Adriatic ports such as Preveza, Vlorë, and Durrës.[64]

See also

- Albania under the Ottoman Empire

- Greece under the Ottoman Empire

- Albanian Pashaliks

- Pashalik of Berat

- Pashalik of Scutari

Notes

References

- ^ Albania and the surrounding world: papers from the British Albanian Colloquium, South East European Studies Association held at Pembroke College, Cambridge, 29–31 March 1994

- ^ Elsie 2012, pg. LVI: "... Ali Pasha, by using a skillful blend of diplomacy and terror, kept his region virtually independent until 1822."

- ^ Fleming 1999, pg 7: "...the nature and content of the diplomatic negotiations between these powers (France, Britain, Russia, Venice, and Austria) and Ali effectively demonstrate that at the turn of the century he was regarded, as he wished to be, as a de facto sovereign political entity."

- ^

Arafat, K.W. (1987). "A Legacy of Islam in Greece: 'Ali Pasha and Ioannina". Bulletin (British Society for Middle Eastern Studies). 14 (2): 176. JSTOR 194383. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

Ali Pasha's creation of a virtually independent pashalik inevitable brought him into conflict with the Porte.

- ^ "Visualizing Ali Pasha Order: Relations, Networks and Scales". Stanford University. Archived from the original on 14 October 2022. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ Fleming 1999, p. 7: "From Ioannina, Ali ruled over a territory that when combined with the neighbouring pasaliks (gubernatorial districts) of his sons covered almost the entirety of what today is mainland Greece. Only Athens and the surrounding portions of Attica were not under his control."

- ^ a b Fleming 1999, p. 59

- ^ Fleming 2014, p. 116.

- ^ Fleming 2014, p. 157.

- ^ Elsie, Robert (ed.). "1813 Thomas Smart Hughes: Travels in Albania". albanianhistory.net.

- ^ Elevating and Safeguarding Culture Using Tools of the Information Society: Dusty traces of the Muslim culture. Earthlab. p. 364. ISBN 978-960-233-187-3.

- ^ Malcolm 2020, p. 163.

- ^ a b c "Ali Pasha – the Lion of Ioánnina". Rough Guides. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ a b Elevating and Safeguarding Culture Using Tools of the Information Society: Dusty traces of the Muslim culture. Earthlab. p. 337. ISBN 978-960-233-187-3.

- ^ Mikropoulos, 2008: 334, 337

- ^ Damianopoulos, Ernest N., 1928- (2012). The Macedonians : their past and present (1st ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-01190-9. OCLC 795517743.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Fleming 2014, p. 63.

- ^ Anscom E. Frederick. Albanians and "Mountain Bandits". Princeton papers: interdisciplinary journal of Middle Eastern studies Markus Wiener Publishers, 2002. ISSN 1084-5666, p. "Voskopoje, southeast Albania, commonly known as Moschopolis" p. 100: "The town was sacked three times during the Ottoman wars with Russia and Austria, in 1769, 1772, and 1789, but not by foreign raiders. The last attack, by Ali Pasha's men, practically destroyed the town. Some of its commerce shifted to Gorice (Korçe, Albania) and Arnavud Belgrad, but those towns could not make good the losses suffered by İskopol."

- ^ Katherine Elizabeth Fleming. The Muslim Bonaparte: diplomacy and orientalism in Ali Pasha's Greece. Princeton University Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0-691-00194-4, p. 36 "...destroyed by resentful Muslim Albanians in 1788"

- ^ Vranousis, Sfyroeras, 1997, p. 247: A few months later, in March 1789, the chieftains of Souli Giorgis and Demetris Botsaris, Lambros Tzavellas, Nicholas and Christos Zervas, Lambros Koutsonikas, Christos Photomaras and Demos Drakos wrote to Sotiris declaring that they and their 2,200 men were ready to fight against Ali Pasha and "the Agarenoi in Roumeli". Ali, who had succeeded Kurt Pasha in the pashalik of Epirus in spring 1789, was informed about the movements of the Souliots, and immediately organized a campaign against them.

- ^ a b Pappas, 1982, p. 252

- ^ Neratzis, Ioannis G. (25 July 2010). Το Σαντζάκιον του Κάρλελι (Κάρλι-ελί) στην περίοδο της Τουρκοκρατίας [The Sanjak of Karleli (Karli-eli) during the period of Turkish rule] (in Greek). Nea Epochi. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Pappas, 1982, p. 253: "Ali immediately ordered an all out attack on Souli in July 1792 with... The Souliotes accepted negotiations and presented the terms which included: the exchange of hostaged Souliotes for prisoners taken from among Ali's troops, the return of all Parasouliote villages to the Souliote confederation"

- ^ Antonina Zhelyazkova.Urgent Anthropology. Vol. 2. Albanian Prospects. Archived 24 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine IMIR, Sofia, 2003. p. 90

- ^ Vickers, Miranda. (1999). The Albanians : a modern history (Rev ed.). London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1-86064-541-0. OCLC 45329772.

- ^ Elevating and Safeguarding Culture Using Tools of the Information Society: Dusty traces of the Muslim culture. Earthlab. pp. 337–338. ISBN 978-960-233-187-3.

- ^ Pappas, 1982, p. 254

- ^ a b c Elevating and Safeguarding Culture Using Tools of the Information Society: Dusty traces of the Muslim culture. Earthlab. p. 338. ISBN 978-960-233-187-3.

- ^ Vakalopoulos 1973, p. 621.

- ^ Pappas, 1982, p. 256

- ^ Vakalopoulos 1973, pp. 621–623.

- ^ Psimouli 2006, pp. 449–450.

- ^ Vakalopoulos 1973, pp. 623–624.

- ^ Moschonas 1975, pp. 398–399.

- ^ Psimouli 2006, pp. 451–452.

- ^ a b c Elevating and Safeguarding Culture Using Tools of the Information Society: Dusty traces of the Muslim culture. Earthlab. p. 339. ISBN 978-960-233-187-3.

- ^ Fleming 1999, p. 73.

- ^ a b Moschonas 1975, p. 399.

- ^ "Ali Paşa Tepelenë". Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ Pappas 1991, pp. 268–269.

- ^ Pappas, Nicholas Charles (1982). Greeks in Russian Military Service in the Late Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries. Stanford University. pp. 265, 388.

Kolokotrones claims that Ali Farmaki and he recruited 3000 Chams, who gathered at Parga to embark first to Lefkas and Zante and then hence to the Peloponnesus, only to have the whole plan aborted by the English capture of Zante (...)

- ^ Fleming 2014, p. 60: "Despite the fact the he used Greek for all courtly dealings, Ali was regarded first and foremost as an Albanian. His use of Greek did not in any way make him Greek, any more than his status as Ottoman appointee made him in some way Ottoman."

- ^ Pappas 1991, p. 269.

- ^ Rowland E. Prothero, ed., The Works of Lord Byron: Letters and Journals, Vol. 1, 1898, "mahometan+buonaparte"&pg=PA252 p. 252 (letter dated Prevesa, 12 November 1809)

- ^ a b Thomas Keightley (1830). History of the War of Independence in Greece. Vol. 1. Edinburgh: Constable.

- ^ Fleming 1999, p. 96.

- ^ Christianity And Islam Under The Sultans Vol II (1929) Author: Hasluck, F.W. Subject: RELIGION. THEOLOGY; Prehistoric and primitive religions Publisher: Oxford at the Clarendon Press.

- ^ Kaser, Karl (1992). Hirten, Kämpfer, Stammeshelden: Ursprünge und Gegenwart des balkanischen Patriarchats (in German). Böhlau Verlag Wien. p. 367. ISBN 978-3-205-05545-7.

Nicht nur die Vlachen, sonder auch vielle Sarakatsanenfamilien sahen sich genotigt, dem Durck Ali Pasas durch Auswnaderung zu entgehen.

- ^ Santas, Constantine (1976). Aristotelis Valaoritis. Boston, Massachusetts: Twayne Publishers. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-8057-6246-4.

Thanasis Vayias, a man who allegedly led the hordes of Ali Pasha against a village of Epirus, Gardiki, resulting in the massacre of seven hundred men, women, and children.

- ^ Potts, Jim (2010). The Ionian Islands and Epirus: A Cultural History. Oxford University Press. pp. 158–159. ISBN 9780199754168.

- ^ Foss, Arthur (1978). Epirus. Faber. ISBN 978-0571104888. p. 139. "Hughes had also admired Derviziana and the prospect across the valley, 'one of the noblest valleys in Epirus. Here he met a shepherd boy with a pipe fashioned from an eagle's wing. This eagle had carried away several lambs in his care so, armed with a long Albanian knife, he had climbed up the mountain steep, grappled with and killed the marauder on its nest. Hugh's hosts had been at the massacre at Gardhiki in Albania when Ali Pasha used Greeks to slaughter the Albanian-Muslim villagers, who had raped his tigress of a mother and his sister. Muslim troops, although loyal to the Vizier, had refused to carry out this instruction."

- ^ Russell, Eugenia; Russell, Quentin (30 September 2017). Ali Pasha, Lion of Ioannina: The Remarkable Life of the Balkan Napoleon. Pen and Sword. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-4738-7722-1.

- ^ Amoretti, Guido (2007). The Serenissima Republic in Greece: XVII- XVIII Centuries : from the Drawings of Captain Antonio Paravia and the Archives of Venice. Omega. p. 160.

The inhabitants, who were mostly Greeks and extremely loyal to the Venetian flag, refused to become Moslem subjects and decided to abandon their home .

- ^ Dakin, Douglas (1973). The Greek Struggle for Independence, 1821-1833. University of California Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-520-02342-0.

- ^ Jim Potts (2010). The Ionian Islands and Epirus: A Cultural History. Oxford University Press. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-19-975416-8.

- ^ a b Kokolakis, Mihalis (2003). Το ύστερο Γιαννιώτικο Πασαλίκι: χώρος, διοίκηση και πληθυσμός στην τουρκοκρατούμενη Ηπειρο (1820–1913) [The late Pashalik of Ioannina: Space, administration and population in Ottoman ruled Epirus (1820–1913)]. Athens: EIE-ΚΝΕ. p. 189. ISBN 960-7916-11-5. "Χωριστή περιφέρεια αποτέλεσε αρχικά και η πόλη της Πάργας. Όπως είναι γνωστό, η Πάργα ανήκε από το 1800 στα εξαρτήματα του προνομιούχου βοϊβοδαλικιού της Πρέβεζας, όπου εντάχθηκαν οι ηπειρωτικές κτήσεις της άλλοτε βενετικής δημοκρατίας αντίθετα όμως με την Πρέβεζα, κατόρθωσε από το 1807 να υποβληθεί πρώτα στη γαλλική και μετά στην αγγλική προστασία. Με την άρση της τελευταίας (1819) η πόλη, ολοκληρωτικά εγκαταλειμμένη από τους κατοίκους της, παραδόθηκε στον Αλή πασά. Ο τελευταίος την εποίκισε με ντόπιους αλβανόφωνους της Τσαμουριάς, στους οποίους ο Κιουταχής θα προσθέσει το 1831 αρκετές οικογένειες μουσουλμάνων προσφύγων της Πελοποννήσου."

- ^ Dixon, Jeffrey C. (2013). Guide to intrastate wars : a handbook on civil wars. Sarkees, Meredith Reid, 1950-. Washington, D.C.: CQ. ISBN 978-1-4522-3420-5. OCLC 906009220.

- ^ Fleming 2014, p. 59: "When, however, Ali in the last years of life found himself opposed by the sultan's troops, he managed to bring to life an anti-Ottoman coalition, gaining the Souliotes' support in part through an appeal to shared Albanian origins." p. 63: "The ersatz alliance between the Souliotes and Ali's Albanians against the sultan's troops was obtained only after Ali's promise that he would restore the Souliotes to their land."

- ^ Victor Roudometof, Roland Robertson (2001), Nationalism, globalization, and orthodoxy: the social origins of ethnic conflict in the Balkans, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001, p. 25, ISBN 978-0-313-31949-5

- ^ "Order of Liabilities: Debt and Credit in Ali Pasha's Regime". Archived from the original on 11 September 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ Neumeier, Mary Emily (2016). "The Architectural Transformation Of The Ottoman Provinces Under Tepedelenli Ali Pasha, 1788-1822" (PDF): 346. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Fleming 2014, p. 46.

- ^ Fleming 2014, pp. 46–47.

- ^ a b Fleming 2014, p. 47.

Sources

- Fleming, K. E. (2014). The Muslim Bonaparte: Diplomacy and Orientalism in Ali Pasha's Greece. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-6497-3.

- Robert Elsie (2012). A Biographical Dictionary of Albanian History. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-78076-431-3.

- Ilıcak, Şükrü, ed. (2021). Those Infidel Greeks: The Greek War of Independence through Ottoman Archival Documents. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-47129-0.

- Malcolm, Noel (2020). Rebels, Believers, Survivors: Studies in the History of the Albanians. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192599223.

- Sakellariou, M. V. (1997), Epirus, 4000 years of Greek history and civilization, Ekdotike Athenon, p. 480, ISBN 978-960-213-371-2,

p. 380

- Vakalopoulos, Apostolos E. (1973). Ιστορία του νέου ελληνισμού, Τόμος Δ': Τουρκοκρατία 1669–1812 – Η οικονομική άνοδος και ο φωτισμός του γένους (Έκδοση Β') [History of modern Hellenism, Volume IV: Turkish rule 1669–1812 – Economic upturn and enlightenment of the nation (2nd Edition)] (in Greek). Thessaloniki: Emm. Sfakianakis & Sons.

- Vakalopoulos, Apostolos E. (1975). "Πελοπόννησος: Η τελευταία περίοδος βενετικής κυριαρχίας (1685–1715)" [Peloponnese: The last period of Venetian rule (1685–1715)]. In Christopoulos, Georgios A. & Bastias, Ioannis K. (eds.). Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, Τόμος ΙΑ΄: Ο Ελληνισμός υπό ξένη κυριαρχία (περίοδος 1669 - 1821), Τουρκοκρατία - Λατινοκρατία [History of the Greek Nation, Volume XI: Hellenism under Foreign Rule (Period 1669 - 1821), Turkocracy – Latinocracy] (in Greek). Athens: Ekdotiki Athinon. pp. 206–209. ISBN 978-960-213-100-8.

- 1822 disestablishments in the Ottoman Empire

- 18th century in Greece

- 19th century in Greece

- States and territories established in 1787

- Former countries in the Balkans

- Eyalets of the Ottoman Empire in Europe

- Ottoman Epirus

- Ottoman Albania

- Ottoman Greece

- 1788 establishments in the Ottoman Empire

- 18th-century establishments in Greece

- Ali Pasha of Ioannina

- Vassal states of the Ottoman Empire