Viking Age

| Part of a series on |

| Scandinavia |

|---|

|

The Viking Age is the name of the period between 793 and 1066 AD in Scandinavia and England, following the Germanic Iron Age (and the Vendel Age in Sweden). During this period, the Vikings, Scandinavian warriors and traders, raided and explored most parts of Europe, south-western Asia, northern Africa and north-eastern North America. Apart from exploring Europe by way of its oceans and rivers with the aid of their advanced navigational skills and extending their trading routes across vast parts of the continent, they also engaged in warfare and looted and enslaved numerous Christian communities of Medieval Europe for centuries, contributing to the development of feudal systems in Europe, which included castles and barons (which were a defense against Viking raids).

Viking society was based on agriculture and trade with other peoples and placed great emphasis on the concept of honour both in combat and in the criminal justice system.

It is unknown what triggered the Vikings' expansion and conquests, but historians have suggested that technological innovations imported from Mediterranean civilizations along with a milder climate led to population growth due to a long period of good crops. Another factor was the destruction of the Frisian fleet by Charlemagne around 785, which interrupted the flow of many trading goods from Central Europe to Scandinavia and led the Vikings to come looking for it themselves. A factor, particularly for the settlement and conquest period that followed the early raids is the internal strife in Scandinavia, which resulted in the progressive centralisation of power in fewer hands. It may be argued that all of the factors above had contributed to the advent of the Viking Age.

Historic overview

The beginning of the Viking Age is commonly given as 793, when Vikings raided the important British island monastery of Lindisfarne[citation needed] (although a minor incursion was recorded in 787); and the end of the Viking Age is traditionally marked by the failed invasion of England, attempted by Harald Hårdråde, who was defeated by the Saxon king Harold Godwinson in 1066. Godwinson himself was subsequently defeated within a month by another Viking descendant, William, Duke of Normandy (Normandy had itself been acquired by Vikings (Normans) in 911).

The clinker-built longships used by the Scandinavians were uniquely suited to both deep and shallow waters, and thus extended the reach of Norse raiders, traders and settlers not only along coastlines, but also along the major river valleys of north-western Europe. Rurik also expanded to the east, and in 859 founded the city of Novgorod (which means "new city") on Volkhov River. His successors (the Rurik Dynasty) moved further founding the first East Slavs state of Kievan Rus with the capital in Kiev, which persisted until 1240, the time of Mongol invasion. According to one author, the word "Rus" originally meant "Viking raider", as distinct from the native Slavic people. Other Norse people, particularly those from the area that is now modern-day Sweden, continued south on Slavic rivers to the Black Sea and then on to Constantinople (which had been established in 667 B.C., and was re-named Constantinople in 330 A.D. by Constantine the Great). Whenever these viking ships would run aground in shallow waters, the Vikings would reportedly turn them on their sides and drag them across the land, into deeper waters.

The Kingdom of the Franks under Charlemagne was particularly hard-hit by these raiders, who could sail down the Seine River with near impunity. Near the end of Charlemagne's reign (and throughout the reigns of his sons and grandsons) a string of heavy raids began, culminating in a gradual Scandinavian conquest and settlement of the region now known as Normandy. The very name "Normandy" itself derives from the Norse settlers who had taken control of the region.

In 911, the French king, Charles the Simple, was able to make an agreement with the Viking warleader Rollo, a chieftain of disputed Norwegian or Danish origins - the material suggesting a Norwegian origin identifies him with Hrolf Gangr, also known as Rolf the Walker. Charles gave Rollo the title of duke, and granted him and his followers possession of Normandy. In return, Rollo swore fealty to Charles, converted to Christianity, and undertook to defend the northern region of France against the incursions of other Viking groups. The results were, in a historical sense, rather ironic: several generations later, the Norman descendants of these Viking settlers not only thereafter identified themselves as French, but carried the French language, and their variant of the French culture into England in 1066, after the Norman Conquest, and became the ruling aristocracy of Anglo-Saxon England.

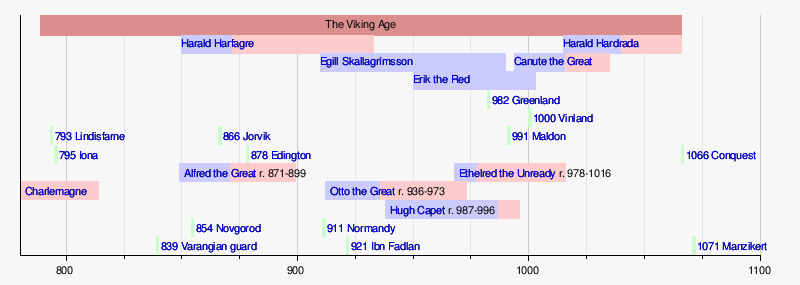

Timeline

Geography

There are various theories concerning the causes of the Viking invasions. For people living along the coast, it would seem natural to seek new land by the sea. Another reason was that during this period England, Wales and Ireland, which were divided into many different warring kingdoms, were in internal disarray, and became easy prey. The Franks, however, had well-defended coasts, and heavily fortified ports and harbours. Pure thirst for adventure may also have been a factor. A reason for the raids is believed by some to be over-population caused by technological advances, such as the use of iron. Although another cause could well have been pressure caused by the Frankish expansion to the south of Scandinavia, and their subsequent attacks upon the Viking peoples. Another possibly-contributing factor is that Harald I of Norway, ("Harald Fairhair") had united Norway around this time, and the bulk of the Vikings were displaced warriors who had been driven out of his kingdom, and who had nowhere to go. Consequently, these Vikings became raiders, in search of subsistence and bases to launch counter-raids against Harald. One theory that has been suggested is that the Vikings would plant crops after the winter, and go raiding as soon as the ice melted on the sea, then returned home with their loot, in time to harvest the crops, and to tell stories of their adventures. They became wandering raiders and mercenaries, like their Celtic cousins.

One important center of trade was at Hedeby. Close to the border with the Franks, it was effectively a crossroads between the cultures, until its eventual destruction by the Norwegians in an internecine dispute around the year 1050. York was the center of the kingdom of Jorvik from 866, and discoveries there show that Scandinavian trade connections in the 10th century reached beyond Byzantium (e.g. a silk cap, a counterfeit of a coin from Samarkand and a cowry shell from the Red Sea or the Persian Gulf), although they could be Byzantine imports, and there is no reason to assume that the Varangians themselves travelled significantly beyond Byzantium and the Caspian Sea.

British Isles

The Danes sailed south, to Frisia, France and the southern parts of England. In the years 1013-1016 Canute the Great succeeded to the English throne.

England

According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, after Lindisfarne was raided in 793, Vikings continued on small-scale raids across England. Viking raiders struck England in 793 and raided a Christian monastery that held Saint Cuthbert’s relics. The raiders killed the monks and captured the valuables. This raid was called the beginning of the “Viking Age of Invasion”, made possible by the Viking longship. There was great violence during the last decade of the 8th century on England’s northern and western shores. While the initial raiding groups were small, it is believed that a great amount of planning was involved. During the winter between 840 and 841, the Norwegians raided during the winter instead of the usual summer. They waited on an island off Ireland. In 865 a large army of Danish Vikings, supposedly led by Ivar, Halfdan and Guthrum arrived in East Anglia. They proceeded to cross England into Northumbria and captured York (Jorvik), where some settled as farmers. Most of the English kingdoms, being in turmoil, could not stand against the Vikings. In 939 Alfred of Wessex managed to keep the Vikings out of his country. Alfred and his successors continued to drive back the Viking frontier and take York. A new wave of Vikings appeared in England in 947 when Erik Bloodaxe captured York. The Viking presence continued through the reign of Canute the Great (1016-1035), after which a series of inheritance arguments weakened the family reign. The Viking presence dwindled until 1066, when the Danes lost their final battle with the English. See also Danelaw.

The Vikings did not get everything their way. In one situation in England, a small Viking fleet attacked a rich monastery at Jarrow. The Vikings were met with stronger resistance than they expected: their leaders were killed, the raiders escaped, only to have their ships beached at Tynemouth and the crews killed by locals. This was one of the last raids on England for about 40 years. The Vikings instead focused on Ireland and Scotland.

Ireland

The Vikings conducted extensive raids in Ireland and founded a few towns, including Dublin. At some points, they seemingly came close to taking over the whole isle; however, the Vikings and Scandinavians settled down and intermixed with the Irish. Literature, crafts, and decorative styles in Ireland and the British Isles reflected Scandinavian culture. Vikings traded at Irish markets in Dublin. Excavations found imported fabrics from England, Byzantium, Persia, and central Asia. Dublin became so crowded by the 11th Century that houses were constructed outside the town walls.

The Vikings pillaged monasteries on Ireland’s west coast in 795, and then spread out to cover the rest of the coastline. The north and east of the island were most affected. During the first 40 years, the raids were conducted by small, mobile Viking groups. From 830 on, the groups consisted of large fleets of Viking ships. From 840, the Vikings began establishing permanent bases at the coasts. Dublin was the most significant settlement in the long term. The Irish became accustomed to the Viking presence. In some cases they became allies and also married each other.

In 832, a Viking fleet of about 120 invaded kingdoms on Ireland’s northern and eastern coasts. Some believe that the increased number of invaders coincided with Scandinavian leaders’ desires to control the profitable raids on the western shores of Ireland. During the mid-830s, raids began to push deeper into Ireland, as opposed to just touching the coasts. Navigable waterways made this deeper penetration possible. After 840, the Vikings had several bases in strategic locations dispersed throughout Ireland.

In 838, a small Viking fleet entered the River Liffey in eastern Ireland. The Vikings set up a base, which the Irish called longphorts. This longphort would eventually become Dublin. After this interaction, the Irish experienced Viking forces for about 40 years. The Vikings also established longphorts in Cork, Limerick, Waterford, and Wexford. The Vikings could sail through on the main river and branch off into different areas of the country.

One of the last major battles involving Vikings was the Battle of Clontarf in 1014, in which Vikings fought both for High King Brian Boru's army and for the Viking-led army opposing the High King. Irish and Viking Literature depict the Battle of Clontarf as a gathering of this world and the supernatural. For example, witches, goblins, and demons were present. A Viking poem portrays the environment as strongly pagan. Valkyries chanted and decided who would live and die.

During the raids of the 800s, incredible pieces of Irish art disappeared.[citation needed] Irish art was fragile and delicate so it was easily destroyed during the raids.[citation needed] Furthermore, workshops used to construct the art disappeared.[citation needed] The Irish art completed in the 8th century was so unique that it was impossible to recreate the achievements that were made.[citation needed] Secrets disappeared as well, including specific processes that could never again be used.[citation needed] There were great changes in metalwork, which was the only area significantly affected by the Viking invaders. [citation needed] The pattern of metalwork changed from ornamentation in gilt bronze to decoration in solid silver. Some of the new styles are reflected in Scandinavian brooches. One of the first traces of Scandinavian influence on Irish metalwork is in Scandinavian brooches, or “tortoise brooches” and “box brooches”. Animals depicted have strange appearances and bodies end in comb patterns. Irish art also strongly influenced Scandinavian decoration since they brought Irish artifacts home. They are similar in that they combine abstract patterns and animals are of importance.

Scotland

While there are few records, it is believed to be clear that a Scandinavian presence in Scotland increased in the 830s. In 839, a large Viking force believed to be Norwegian invaded the Earn valley and Tay valley which were central to the Pictish kingdom. They slaughtered Eoganan, king of the Picts, and his brother, the vassal king of the Scots. They also killed many members of the Pictish aristocracy. The sophisticated kingdom that had been built fell apart, as did the Pictish leadership. The foundation of Scotland under Kenneth MacApalpin is traditionally attributed to the aftermath of this event.

Wales

Wales was not colonised by the Vikings, as was the case with eastern England and Ireland, but still southern Wales suffered under repeated raids by Vikings, especially from Viking controlled Ireland [1]. During this period Wales was split into several kingdoms and the Vikings took advantage of this instability in the region by raiding, however they were not able to set up a Viking state or control Wales due to the powerful forces of Welsh kings and unlike in Scotland the aristocracy was relatively unharmed.

Other territories

Iceland

The Norwegians travelled to the north-west and west, founding vibrant communities in the Faroe Islands, the Shetlands, the Orkneys, Iceland, Ireland and Great Britain. Apart from Britain and Ireland, Norwegians mostly found largely uninhabited land, and established settlements in those places. According to the saga of Erik the Red when Erik the Red was exiled from Iceland he went west. There he found a land that he named "Greenland" to attract people from Iceland to settle it with him.

Greenland

The Viking Age settlements in Greenland were established in the sheltered fjords of the southern and western coast. They settled in three separate areas along approximately 650 kilometers of the western coast.

- The Eastern Settlement (61°00′N 45°00′W / 61.000°N 45.000°W). The remains of ca. 450 farms have been found here. Erik the Red settled at Brattahlid on Ericsfjord.

- The Middle Settlement (62°00′N 48°00′W / 62.000°N 48.000°W) near modern Ivigtut, consisting of ca. 20 farms.

- The Western Settlement, at modern Godthabsfjord (64°00′N 51°00′W / 64.000°N 51.000°W), established before the 12th century. It has been extensively excavated by archaeologists.

Southern and Eastern Europe

The Swedish Varangians sailed east into Russia, where Rurik founded the first Russian state at Novgorod (called Garðaríke), and on the rivers south to the Black Sea, Miklagard (Constantinople) and the Byzantine Empire. See also Serkland and Biarmland.

America

In about the year 986 A.D., North America was reached by Bjarni Herjólfsson. Leif Ericson and Þórfinnur Karlsefni from Greenland attempted to settle the land, which they dubbed Vinland about the year 1000 A.D. A small settlement was placed on the northern peninsula of Newfoundland, near L'Anse aux Meadows, but previous inhabitants, and a cold climate brought it to an end within a few years (see Freydís Eiríksdóttir). The archaeological remains are now a UN World Heritage Site[1].

Technology

The Vikings were equipped with the then technologically superior longships; for purposes of conducting trade, however, another type of ship, the knarr, wider and deeper in draught, were customarily used. The Vikings were competent sailors, adept in land warfare as well as at sea, and they often struck at accessible and poorly-defended targets, usually with near impunity. It is the effectiveness of these tactics that earned them their formidable reputation as raiders and pirates, and the chroniclers paid little attention to other aspects of medieval Scandinavian culture. This is further accentuated by the absence of contemporary primary source documentation from within the Viking Age communities themselves, and little documentary evidence is available until later, when Christian sources begin to contribute. It is only over time, as historians and archaeologists have begun to challenge the one-sided descriptions of the chroniclers, that a more balanced picture of the Norsemen has begun to become apparent.

Besides allowing the Vikings to travel vast distances, their longships gave them certain tactical advantages in battle. They could perform very efficient hit-and-run attacks, in which they approached quickly and unexpectedly, then left before a counter-offensive could be launched. Because of their negligible draught, longships could sail in shallow waters, allowing the Vikings to travel far inland along the rivers. Their speed was also prodigious for the time, estimated at a maximum of 14 or 15 knots. The use of the longships ended when technology changed, and ships began to be constructed using saws instead of axes. This led to a lesser quality of ships; and, together with an increasing centralisation of government in the Scandinavian countries, the old system of Leidang—a fleet mobilization system, where every Skipen (ship community) had to deliver one ship and crew—was discontinued. Shipbuilding in the rest of Europe also led to the demise of the longship for military purposes. By the 11th and 12th centuries, fighting ships began to be built with raised platforms fore and aft, from which archers could shoot down into the relatively low longships.

There is an archaeological find in Sweden of a bone fragment that has been fixated with in-operated material; the piece is as yet undated. These bones might possibly be the remains of a trader from the Middle East.

The nautical achievements of the Vikings were quite exceptional. For instance, they made distance tables for sea voyages that were so exact, that they only differ 2-4% from modern satellite measurements, even on long distances, such as across the Atlantic Ocean.

There is a finding known as the Visby lenses at the island of Gotland in Sweden that might possibly be components from a telescope, although the telescope was "invented" in the 1600's.[2]

Religion and Archaeology

At the start of the Viking age, the Vikings adhered to the Norse religion and system of beliefs. Their pantheon of gods and goddesses included their belief in Valhalla, or "Heaven for Warriors" (which partly explains their war-like nature). According to Viking beliefs, valorous Viking chieftains would please their war-gods by their bravery, and would become "worth-ship"; that is, the chieftain would earn a "burial at sea", or a burial on land, which may have included a ship, treasure, weapons, tools, clothing and even live slaves and women buried alive with the dead chieftain, for his "journey to Valhalla, and adventure and pleasure in the after-life". Then, living sages would compose sagas about the exploits of these chieftains, keeping their memories alive on earth as well (a different kind of "immortality"). These sometimes vast, often rich burial mounds have been found extensively through-out the regions visited by the Vikings, and have provided archaeologists with rich material about the Vikings.

Towards the end of the viking age, more and more Scandinavians converted to Christianity. The first christian king of Norway was Haakon the Good who died in 961, in Iceland, Christianity was officially adopted at the Althing in 1000. The introduction of Christianity did not instantaneously bring an end to the viking voyages, but it may have been a contributing factor in bringing the Viking age to a close.

Trading cities

Some of the most important trading ports during the period include both existing and ancient cities such as Jelling (Denmark), Ribe (Denmark), Roskilde (Denmark), Hedeby (Germany), Bergen (Norway), Kaupang (Norway), Birca (Sweden), Bordeaux (France), Jorvik (England), Dublin (Ireland) and Aldeigjuborg (Russia).

See also

Place names

- Danelaw

- Bjarmland

- Helluland

- Markland

- Vinland

- Hjaltland

- Gardariki

- Serkland

- Miklagard

- Greenland

- Iceland

External links

- Jorvik and the Viking Age (866 AD - 1066 AD)

- Old Norse litterature from «Kulturformidlingen norrøne tekster og kvad» Norway.

- BBC - History - Blood of the Vikings

- All About Vikings

References

- Carey, Brian Todd. “Technical marvels, Viking longships sailed seas and rivers, or served as floating battlefields,” Military History 19, no. 6 (2003): 70-72.

- Forte, Angelo. Oram, Richard. Pedersen, Frederik. Viking Empires. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Henry, Francoise. Irish Art in the Early Christian Period. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1940.

- Hudson, Benjamin. Viking Pirates and Christian Princes: Dynasty, Religion, and Empire in North America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Maier, Bernhard. The Celts: A history from earliest times to the present. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 2003.