Debate

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Debate is a process that involves formal discussion on a particular topic. In a debate, opposing arguments are put forward to argue for opposing viewpoints. Debate occurs in public meetings, academic institutions, and legislative assemblies.[1] It is a formal type of discussion, often with a moderator and an audience, in addition to the debate participants.

Logical consistency, factual accuracy and some degree of emotional appeal to the audience are elements in debating, where one side often prevails over the other party by presenting a superior "context" or framework of the issue. In a formal debating contest, there are rules for participants to discuss and decide on differences, within a framework defining how they will do it.

Debating is carried out in debating chambers and assemblies of various types to discuss matters and to make resolutions about action to be taken, often by voting.[citation needed] Deliberative bodies such as parliaments, legislative assemblies, and meetings of all sorts engage in debates. In particular, in parliamentary democracies a legislature debates and decides on new laws. Formal debates between candidates for elected office, such as the leaders debates, are sometimes held in democracies. Debating is also carried out for educational and recreational purposes,[2] usually associated with educational establishments and debating societies.[3]

Informal and forum debate is relatively common, shown by TV shows such as the Australian talk show, Q+A.[according to whom?] The outcome of a contest may be decided by audience vote, by judges, or by some combination of the two.[citation needed]

History

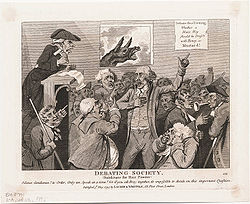

Debating in various forms has a long history and can be traced back to the philosophical and political debates of Ancient Greece, such as Athenian democracy, Shastrartha in Ancient India. Modern forms of debating and the establishment of debating societies occurred during the Age of Enlightenment in the 18th century.[citation needed]

Emergence of debating societies

Debating societies emerged in London in the early eighteenth century, and soon became a prominent fixture of national life.[citation needed] The origins of these societies are not certain in many cases, although by the mid-18th century, London fostered an active debating society culture.[citation needed] Debating topics covered a broad spectrum of topics while the debating societies allowed participants from both genders and all social backgrounds, making them an excellent example of the enlarged public sphere of the Age of Enlightenment.[4] Debating societies were a phenomenon associated with the simultaneous rise of the public sphere,[5] a sphere of discussion separate from traditional authorities and accessible to all people that acted as a platform for criticism and the development of new ideas and philosophy.[6]

John Henley, a clergyman,[7] founded an Oratory in 1726 with the principal purpose of "reforming the manner in which such public presentations should be performed."[8] He made extensive use of the print industry to advertise the events of his Oratory, making it an omnipresent part of the London public sphere. Henley was also instrumental in constructing the space of the debating club: he added two platforms to his room in the Newport district of London to allow for the staging of debates, and structured the entrances to allow for the collection of admission. These changes were further implemented when Henley moved his enterprise to Lincoln's Inn Fields. The public was now willing to pay to be entertained, and Henley exploited this increasing commercialization of British society.[9] By the 1770s, debating societies were firmly established in London society.[10]

The year 1785 was pivotal: The Morning Chronicle announced on March 27:[11]

The Rage for public debate now shews itself in all quarters of the metropolis. Exclusive of the oratorical assemblies at Carlisle House, Free-mason's Hall, the Forum, Spring Gardens, the Cassino, the Mitre Tavern and other polite places of debating rendezvous, we hear that new Schools of Eloquence are preparing to be opened in St. Giles, Clare-Market, Hockley in the Hole, Whitechapel, Rag-Fair, Duke's Place, Billingsgate, and the Back of the Borough.

In 1780, 35 differently named societies advertised and hosted debates for anywhere between 650 and 1200 people.[12] The question for debate was introduced by a president or moderator who proceeded to regulate the discussion. Speakers were given set amounts of time to argue their point of view, and, at the end of the debate, a vote was taken to determine a decision or adjourn the question for further debate.[13] Speakers were not permitted to slander or insult other speakers, or diverge from the topic at hand, again illustrating the value placed on politeness by late 18th century debaters.[10]

Student debating societies

Princeton University in the future United States was home to a number of short-lived student debating societies throughout the mid-1700s, and its influential American Whig Society was co-founded in 1769 by future revolutionary James Madison. The first of the post-revolutionary debating societies, the Dialectic and Philanthropic Societies, were formed at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1795 and are still active.

The first student debating society in Great Britain was the St Andrews Debating Society, formed in 1794 as the Literary Society. The Cambridge Union Society was founded in 1815, and claims to be the oldest continually operating debating society in the World.[14] This claim is arguably valid because Princeton's societies had been shut down during the American Revolutionary War, while the UNC societies' operations were briefly suspended during the American Civil War.

Over the next few decades, similar societies emerged at several other prominent universities. Examples include the Oxford Union, the Yale Political Union and the Conférence Olivaint.

Debating for decision-making

Parliamentary debate

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2012) |

In parliaments and other legislatures, members debate proposals regarding legislation, before voting on resolutions which become laws. Debates are usually conducted by proposing a law, or changes to a law known as amendments. Members of the parliament, assembly or congress then discuss the proposal and cast their vote for or against such a law.

Emergency debating

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2015) |

In some countries (e.g., Canada[15] and the UK[16]) members of parliament may request debates on urgent matters of national importance. If the Speaker grants such a request, an emergency debate is usually held before the end of the next sitting day.

Debate between candidates for high office

In jurisdictions which elect holders of high political office such as president or prime minister, candidates sometimes debate in public, usually during a general election campaign.

U.S. presidential debates

Since the 1976 general election, debates between presidential candidates have been a part of U.S. presidential campaigns. Unlike debates sponsored at the high school or collegiate level, the participants and format are not independently defined. Nevertheless, in a campaign season heavily dominated by television advertisements, talk radio, sound bites, and spin, they still offer a rare opportunity for citizens to see and hear the major candidates side by side. The format of the presidential debates, though defined differently in every election, is typically more restrictive than many traditional formats, forbidding participants to ask each other questions and restricting discussion of particular topics to short time frames.

The presidential debates were initially moderated in 1976, 1980, and 1984 by the League of Women Voters, but the Commission on Presidential Debates (CPD) was established in 1987 by the Republican and Democratic parties. The presidential debate's primary purpose is to sponsor and produce debates for the United States presidential and vice presidential candidates and to undertake research and educational activities relating to the debates.[citation needed] The organization, which is a nonprofit, nonpartisan corporation, sponsored all of the presidential debates in 1988, 1992, 1996, 2000, 2004, 2008, 2012, 2016, and 2020.

However, in announcing its withdrawal from sponsoring the debates, the League of Women Voters stated that it was withdrawing "because the demands of the two campaign organizations would perpetrate a fraud on the American voter."[17] In 2004, the Citizens' Debate Commission was formed in the hope of establishing an independent sponsor for presidential debates, with a more voter-centric role in the definition of the participants, format, and rules.

Competitive debating

In competitive debates, teams compete against each other and are judged the winner by a list of criteria that is usually based around the concepts of "content, style and strategy".[18] There are many different styles of competitive debating, organizations and rules.

Competitive debating is carried out at the local, national, and international level.[19]

In schools and colleges, competitive debating often takes the form of a contest with explicit rules. It may be presided over by one or more judges or adjudicators. Both sides seek to win against the other while following the rules. One side is typically in favor of (also known as "for", "Affirmative", or "Pro") or opposed to (also known as "against", "Negative", "Con") a statement, proposition, moot or Resolution. The "for" side must state points that will support the proposition; the "against" side must refute these arguments sufficiently to falsify the other side. The "against" side is not required to propose an alternative but it must substantiate its own negation if no other position is possible. For instance, let x be a boolean. If the "for" side says x = true, the "against" side must say x = false. The "against" side cannot simply say "I am not convinced that x = true" if they both want a debate. Both sides are required to embrace and defend their own positions. Otherwise, it is not a debate but simply a discussion of a controversy where one side solely attempts to convince the other side or the other listeners to its position.

Forms of competitive debating

Australasia debating

The Australasian style debate consists of two teams, each consisting of three people, who debate over an issue that is commonly called a topic or proposition. The issue, by convention, is presented in the form of an affirmative statement beginning with "That", for example, "That cats are better than dogs", or "This House", for example, "This House would establish a world government". The topic subject may vary from region to region. Most topics, however, are usually region-specific to facilitate interest by both the participants and their audiences.[original research?]

Each team has three members, each of whom is named according to their team and speaking position within his/her team. For instance, the second speaker of the affirmative team to speak is called the "Second Affirmative Speaker" or "Second Proposition Speaker", depending on the terminology used. Each of the speakers' positions is based around a specific role. For example, the third speaker has the opportunity to make a rebuttal towards the opposing team's argument by introducing new evidence to add to their position. The last speaker is called the "Team Advisor/Captain". Using this style, the debate is finished with a closing argument by each of the first speakers from each team and new evidence may not be introduced. Each of the six speakers (three affirmative and three negative) speak in succession to each other beginning with the Affirmative Team. The speaking order is as follows: First Affirmative, First Negative, Second Affirmative, Second Negative, Third Affirmative, and finally Third Negative.[20] "Points of Information", more commonly known as "POIs" are often used in Australian and New Zealand Secondary School level debating. A Point of Information (POI) is when a member of the team opposing that of the current speaker gets to briefly interrupt the current speaker, offering a POI in the form of a question or a statement.

The context in which the Australasia style of debate is used varies, but in Australia and New Zealand is mostly used at the Primary and Secondary school level, ranging from small informal one-off intra-school debates to larger more formal inter-school competitions with several rounds and a finals series which occur over a year.[21]

European square debating

This is a Paris-style inspired format, specifically suited for Council of Europe simulation.[according to whom?] Four teams representing four major European nations (for instance France, the United Kingdom, Germany, and Russia) confront each other on a policy debate including two broad coalitions (online examples for sustainable energy [22] and defence).[23] Each team is composed of two speakers (the Prime Minister and the Foreign Secretary). The debate starts with the first speaker from France, followed by the first speaker of Germany (the opposite side), followed by the second speaker of France and the second speaker of Germany. The debate continues with the first speaker of the United Kingdom, followed by the first speaker of Russia and it goes on with the respective second speakers. Each debater speaks for 5 minutes. The first and the last minutes are protected time: no Points of Information may be asked. During the rest of the speech, the speaker may be interrupted by Points of Information (POIs) from the opposite countries (debaters from France and UK may ask POIs to debaters representing Germany and Russia and vice versa, respectively). The format forces each debater to develop a winning strategy while respecting the coalition. This format was commonly developed by The Franco-British Comparative Project[24] and Declan McCavanna, Chairman of the FDA [25] and was featuring France, the UK, Germany, Russia and Italy.

Extemporaneous speaking

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2015) |

Extemporaneous speaking is a style that involves no planning in advance, and two teams with a first and second speaker. While a majority of judges will allow debaters to cite current events and various statistics (of which opponents may question the credibility) the only research permitted are one or more articles given to the debaters along with the resolution shortly before the debate. It begins with an affirmative first-speaker constructive speech, followed by a negative; then an affirmative and negative second-speaker constructive speech respectively. Each of these speeches is six minutes in length, and is followed by two minutes of cross examination. There is then an affirmative and negative first-speaker rebuttal, and a negative and affirmative second-speaker rebuttal, respectively. These speeches are each four minutes long. No new points can be brought into the debate during the rebuttals.

This style of debate generally centers on three main contentions, although a team can occasionally use two or four. In order for the affirmative side to win, all of the negative contentions must be defeated, and all of the affirmative contentions must be left standing. Most of the information presented in the debate must be tied in to support one of these contentions, or "signposted". Much of extemporaneous speaking is similar to the forms known as policy debate and Congressional Debate. One main difference with both of them, however, is that extemporaneous speech focuses less on the implementation of the resolution. Also, Extemporaneous Speech is considered in more areas, especially in the United States, as a form of Speech, which is considered separate from debate, or itself a form of debate with several types of events.[26]

Impromptu debating

Impromptu debating is a relatively informal style of debating, when compared to other highly structured formats. The topic for the debate is given to the participants between fifteen and twenty minutes before the debate starts. The debate format is relatively simple; each team member of each side speaks for five minutes, alternating sides. A ten-minute discussion period, similar to other formats' "open cross-examination" time follows, and then a five-minute break (comparable to other formats' preparation time). Following the break, each team gives a 4-minute rebuttal.

Jes debating

This style of debate is particularly popular in Ireland at secondary school level.[according to whom?] Developed in Coláiste Iognáid (Galway) over the last ten years, the format has five speakers: two teams and a single 'sweep speaker' on each side.[clarification needed] Speeches last 4:30 minutes with 30 seconds protected from POIs at either end of the debate. Adjudication will depend on BP (British Parliament) marking[further explanation needed], but with particular recognition of principled debating. A ten-minute open house will also be adjudicated. Traditionally, the motion is always opposed in the final vote.[citation needed]

Lincoln–Douglas debating

Lincoln-Douglas debating is primarily a form of United States high school debate (though it also has a college form called NFA LD) named after the 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debates. It is a one-on-one event focused mainly on applying philosophical theories to real world issues. Debaters normally alternate sides from round to round as either the "affirmative", which upholds the resolution, or "negative", which attacks it. The resolution, which changes bimonthly, asks whether a certain policy or action conforms to a specific value.

Though established as an alternative to policy debate, there has been a strong movement to embrace certain techniques that originated in policy debate (and, correspondingly, a strong backlash movement). Plans, counterplans, critical theory, postmodern theory, debate about the theoretical basis and rules of the activity itself, and critics have all reached more than occasional, if not yet universal, usage. Traditional L-D debate attempts to be free of policy debate "jargon". Lincoln-Douglas speeches can range from a conversational pace to well over 300 words per minute (when trying to maximize the number of arguments and depth of each argument's development). This technique is known as spreading, and originated in policy debate tactics. There is also a growing emphasis on carded evidence, though still much less than in policy debate. These trends have created a serious rift within the activity between the debaters, judges, and coaches who advocate or accept these changes, and those who vehemently oppose them.

Policy and Lincoln-Douglas debate tournaments are often held concurrently at the same school or organization. One organization that offers Lincoln-Douglas debate is NCFCA?

Mace debating

The Mace debating style is prominent in Britain and Ireland at the school level. Two opposing teams, consisting of two people, debate an affirmative motion (e.g. "This house would give prisoners the right to vote",) which one team will propose and the other will oppose. Each speaker will make a seven-minute speech in the order; 1st Proposition, 1st Opposition, 2nd Proposition, 2nd Opposition. After the first minute of each speech, members of the opposing team may request a 'point of information' (POI). If the speaker accepts they are permitted to ask a question. POI's are used to pull the speaker up on a weak point, or to argue against something the speaker has said. However, after 6 minutes, no more POIs are permitted. After all four debaters have spoken, the debate will be opened to the floor, in which members of the audience will put questions to the teams. After the floor debate, one speaker from each team (traditionally the first speaker), will speak for 4 minutes. In these summary speeches it is typical for the speaker to answer the questions posed by the floor, as well as any questions the opposition may have put forward, before summarising his or her own key points.[according to whom?] In the Mace format, emphasis is typically on analytical skills, entertainment, style and strength of argument.[according to whom?] The winning team will typically have excelled in most, if not all, of these areas.

Mock trial

Model United Nations

Moot court

Offene parlamentarische Debatte (OPD)

The offene parlamentarische Debatte (Open Parliamentary Debate, OPD) is a German competitive debating format. It was developed by the debate club Streitkultur Tübingen and was used for the first time in a tournament in 2001.[27] It aims to combine the advantages of parliamentary debates and public audience debates: each of the two teams has three speakers, and in addition the debate includes three independent "free speakers". Clubs using OPD exist in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Italy.[28]

Oxford-style debating

Derived from the Oxford Union debating society of Oxford University, Oxford-style debating is a competitive debate format featuring a sharply assigned motion that is proposed by one side and opposed by another. A winner is declared in an Oxford-Style debate either by the majority or by which team has swayed more audience members between the two votes.[29] Oxford-style debates follow a formal structure that begins with audience members casting a pre-debate vote on the motion that is either for, against or undecided. Each panellist presents a seven-minute opening statement, after which the moderator takes questions from the audience with inter-panel challenges.[30] Finally, each panellist delivers a two-minute closing argument, and the audience delivers their second (and final) vote for comparison against the first.[31]

Paris-style debating

This is a format specifically used in France (though the debates are commonly held in English). Two teams of five debate on a given motion. One side is supposed to defend the motion while the other must defeat it. The debate is judged on the quality of the arguments, the strength of the rhetoric, the charisma of the speaker, the quality of the humor, the ability to think on one's feet, and teamwork.

The first speaker of the Proposition (Prime Minister) opens the debate, followed by the first speaker of the Opposition (Shadow Prime Minister), then the second speaker of the Proposition and so on.

Every speaker speaks for 6 minutes. After the first minute and before the last minute, debaters from the opposite team may ask Points of Information, which the speaker may accept or reject as he wishes (although he is supposed to accept at least two).

The French Debating Association[25] organizes its National Debating Championship upon this style.[32]

Parliamentary debating

Parliamentary debate (sometimes referred to as "parli" in the United States, or "BP" in the rest of the world[according to whom?]) is conducted under rules derived from British parliamentary procedure, though parliamentary debate now has several variations including the British, Canadian and American. It features the competition of individuals in a multi-person setting. It borrows terms such as "government" and "opposition" from the British parliament (although the term "proposition" is sometimes used rather than "government" when debating in the United Kingdom).

Throughout the world, parliamentary debate is what most countries know as "debating", and is the primary style practiced in the United Kingdom, India, Greece and most other nations.[according to whom?] The premier event in the world of parliamentary debate, the World Universities Debating Championship, is conducted in the British Parliamentary style.

British Parliamentary debating

The British Parliamentary (BP) debating style involves four teams: "government" or "proposition" (one opening, one closing) teams support the motion, and two "opposition" teams (one opening, one closing) oppose it. The closing team of each side must either introduce a new substantive point (outward extension) or expand on a previous point made by their opening team (inward extension), all whilst agreeing with their opening team yet one-upping them, so to speak.[neutrality is disputed] In a competitive round, the teams are ranked first to fourth with the first place team receiving 3 points, the second receiving 2, the third receiving 1 and the fourth place receiving no points. This is the style used by the World Universities Debating Championship (WUDC).[citation needed]

However, even within the United Kingdom, British Parliamentary style is not used exclusively; the English-Speaking Union (ESU) runs national championships for both universities (John Smith Memorial Mace) and schools (ESU Schools Mace), (including representation from Ireland) in a unique "Mace" format named after the competition, while there are numerous standalone BP competitions hosted by universities and schools across the UK and Ireland throughout the year.[citation needed]

Canadian Parliamentary debating

The Canadian Parliamentary debating style involves one "government" team and one "opposition" team. On the "government" side, there is the "Prime Minister" and the "Minister of the Crown". On the "opposition" side, there is the "Leader of the Opposition" and the "Shadow Minister". In most competitive situations, it is clear what the motion entails and it must be addressed directly. The debate is structured with each party speaking in a particular order and for a define length of time. However, unlike a cross-examination style debate – another dominant debate style in Canada – Parliamentary debate involves parliamentary rules and allows interruptions for points of order.

In very few cases, the motion may be "squirrelable".[citation needed] This means that the assigned motion is not intended to be debated, and may even be a quote from a film or a song.[example needed] The "government" team then "squirrels" the motion into something debatable by making a series of logical links between the proposed motion and the one they propose to debate. This makes the debate similar to a prepared debate for the "government" team and an impromptu debate for the "opposition" team.

In Canada, debating tournaments may involve a mix of parliamentary and cross-examination-style debate, or be entirely one style or the other. Competitive debating takes place in English, French, or bilingual style – in which approximately 50% of content must be in each language.

American Parliamentary debating

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2015) |

In the United States the American Parliamentary Debate Association is the oldest national parliamentary debating organization, based on the East Coast and including the Ivy League.[33] The more recently founded National Parliamentary Debate Association (NPDA) is now the largest collegiate sponsor.[according to whom?]

Brazilian Parliamentary debating

The Brazilian Parliamentary Debate, also known as "Parli Brasil",[34] involves a "proposition team", that will support the motion, and an "opposition team", who will oppose the motion.

It is based on the British Parliamentary style, but the primary difference is that the proposition's members are not called "government", since not only the political government congressmen of that country can introduce new parliamentary topics. In other words, the government can support or oppose the topic in session on the Congress. This way, using "government" as a synonym to "proposition teams" could create confusion about how the speakers are going to position themselves on debate.

Therefore, the speakers at the debate are called "First Member of Proposition", "First Member of Opposition", "Second Member of Proposition", and so on.

It is the most used competitive debating style used in Brazil; it is used at the official competitions of the Instituto Brasileiro de Debates (Brazilian Institute of Debates).

At Parli Brasil, every speaker speaks for 7 minutes, with 15 seconds of tolerance after that. After the first minute and before the last minute, debaters from the opposite team may ask Points of Information, which the speaker may accept or reject as he wishes (although he is supposed to accept at least one).

Another major difference between Brazilian scene and the Worlds is that Brazilians tournaments use to present themes weeks before the tournament, with the motion only being presented 15 minutes before the debate, as usual BP. Some tournaments, such as GV Debate and Open de Natal are changing this, too. The presence of themes make some differences in the strategy in comparison to the Worlds.

However, there is no unique model in Brazil because many clubs debates were created before the creation of "Parli Brazil" and not all modified their rules. This is the case, for example, of the UFC Debate Society in Fortaleza ("Sociedade de Debates da UFC") which was established in 2010.[35] In 2013, UFRN Debate Society was created ("Sociedade de Debates da UFRN") also made some changes based on the old "Clube de Debates de Natal" (Debate Club in Natal, Rio Grande do Norte).[36]

The model "Parli Brazil" only started its activities in 2014 with the realization of the I Brazilian Championship of Debates in the city of Belo Horizonte, making the second edition in the city of Fortaleza and the third is scheduled to take place in the city of Florianópolis.[37] Since then, they were also created UFSC Debate Society ("Sociedade de Debates da UFSC") in 2014[38] and the UFRJ Debate Society ("Sociedade de Debates da UFRJ") on June 25, 2015,[39] and others.

At IV Open Minas, hosted by Brazilian Institute of Debates as a prep for CBD, some changes were implemented, when rules and reasoning stopped being judging criteria. The changes were adopted at V Brazilian Championship of Debates.

Policy debating

Policy debate is a form of speech competition in which teams of two advocate for and against a resolution that typically calls for policy change by the United States federal government. It is also called cross-examination debate (sometimes shortened to Cross-X, CX, or C-X) because of the 3-minute questioning period following each constructive speech. Affirmative teams generally present a plan as a proposal to implement the resolution. The negative will generally try to prove that it would be better not to do the plan or that the opportunity costs to the plan are so great that it should not be implemented.

Public debating

Public debate may mean simply debating by the public, or in public. The term is also used for a particular formal style of debate in a competitive or educational context. Two teams of two compete through six rounds of argument, giving persuasive speeches on a particular topic.[40]

Public forum debating

"Public forum" debating combines aspects of both policy debate and Lincoln-Douglas debate, but makes them easily understood by the general public by having shorter speech lengths, and long questioning periods, called "cross-fires", where the debaters interact. The basis of this type of debate is to appeal for anyone who is eligible to become a jury member unlike policy debate or Lincoln-Douglas debate which requires more experience in debate to judge.[citation needed]

Simulated legislature

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2015) |

High school debate events such as Congressional Debate, Model United Nations, European Youth Parliament, Junior State of America and the American Legion's Boys/Girls State attempt to stimulate the debating environment of legislatures.

Tibetan Buddhist debating

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2015) |

This is a traditional Buddhist form of debating that was influenced by earlier Indian forms.[original research?] The debating style was brought to and evolved within Tibet. This style includes two individuals, one functioning as the Challenger (questioner) and the other as the Defender (answerer). The debaters must depend on their memorization of the points of doctrine, definitions, illustrations, and even whole text, together with their own measure of understanding gained from instruction and study.

At the opening of a session of debate, the standing Challenger claps his hands together and recites the seed syllable of Manjushri, "Dhih". Manjushri is the manifestation of the wisdom of all the Buddhas and, as such, is the special deity of debate. In debate, one must have a good motivation, the best of which is to establish all beings in liberation.[according to whom?]

A characteristic of the Tibetan Buddhist style of debating is the hand gestures used by debaters. When the Challenger first puts their question to the sitting Defender, their right hand is held above the shoulder at the level of their head and the left hand is stretched forward with the palm turned upward. At the end of their statement, the Challenger punctuates by loudly clapping together their hands and simultaneously stomping their left foot. They then immediately draw back their right hand with the palm held upward and at the same time, hold forth their left hand with the palm turned downward. This motion of drawing back and clapping is done with the flow of a dancer’s movements.[neutrality is disputed] Holding forth the left hand after clapping symbolizes closing the door to rebirth in the helpless state of cyclic existence.[neutrality is disputed] The drawing back and upraising of the right hand symbolizes one’s will to raise all sentient beings up out of cyclic existence and to establish them in the omniscience of Buddhahood. The left hand represents "Wisdom" — the "antidote" to cyclic existence. The right hand represents "Method"[according to whom?] — the altruistic intention to become enlightened, motivated by great love and compassion for all sentient beings. The clap represents a union of Method and Wisdom. In dependence on the union of Method and Wisdom, one is able to attain Buddhahood.[41]

Turncoat debating

In this style of debating, the same speaker shifts allegiance between "For" and "Against" the motion. It is a solo contest, unlike other debating forms. Here, the speaker is required to speak for 2 minutes "For the motion", 2 minutes "Against the motion" and finally draw up a 1-minute conclusion in which the speaker balances the debate. At the end of the fifth minute the debate will be opened to the house, in which members of the audience will put questions to the candidate which they will have to answer. In the Turncoat format, emphasis is on transitions, the strength of argument and balancing of opinions.[clarification needed]

International Groups and Events

Asian Universities Debating Championship

United Asian Debating Championship is the biggest university debating tournament in Asia, where teams from the Middle East to Japan[citation needed] come to debate. It is traditionally hosted in southeast Asia where participation is usually highest compared to other parts of Asia.

Asian debates are largely an adaptation of the Australasian format. The only difference is that each speaker is given 7 minutes of speech time and there will be points of information (POI) offered by the opposing team between the 2nd to 6th minutes of the speech. This means that the 1st and 7th minute is considered the 'protected' period where no POIs can be offered to the speaker.

The debate will commence with the Prime Minister's speech (first proposition) and will be continued by the first opposition. This alternating speech will go on until the third opposition. Following this, the opposition bench will give the reply speech.

In the reply speech, the opposition goes first and then the proposition. The debate ends when the proposition ends the reply speech. 4 minutes is allocated for the reply speech and no POI's can be offered during this time.

International Public Debate Association

This article appears to contradict the article International Public Debate Association. (August 2015) |

The International Public Debate Association (IPDA), inaugurated on February 15, 1997 at St. Mary's University (Texas) in San Antonio, Texas, is a national debate league currently active primarily in the United States. Among universities, it is unlikely that IPDA is the fastest growing debate association within the United States.[citation needed] Although evidence-based arguments are used, the central focus of IPDA is to promote a debate format that emphasizes public speaking and real-world persuasion skills over the predominate use of evidence and speed.[according to whom?] To further this goal, IPDA predominantly uses lay judges in order to encourage an audience-centered debate style[citation needed]. Furthermore, although the main goal of the debater is to persuade the judge, IPDA also awards the best speakers within each tournament.

IPDA offers both "team debating" where two teams, consisting of two people, debate and individual debate. In both team and individual debate a list of topics are given to the two sides thirty minutes before the start of the round. A negotiation ensues to pick a topic. The sides, one affirming the resolution and one negating the resolution, then prepare an opening speech, a cross-examination of the other side, and closing remarks for the round.

While most member programs of the International Public Debate Association are associated with colleges or universities, participation in IPDA tournaments is open to anyone whose education level is equivalent to high school graduate or higher.[according to whom?]

World Universities Peace Invitational Debate (WUPID)

WUPID is an invitational tournament that employs the BP or Worlds format of debating. It invites the top 30 debating institutions in accordance to the list provided by the World Debate Website administered by Colm Flynn. If any or some of the teams cannot participate than replacements would be called in from the top 60 teams or based on strong recommendations from senior members of the University Debating community.

WUPID was first held in December 2007 with Sydney University being crowned champion. The second installation in 2008 saw Monash taking the trophy home. The third WUPID was held in Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM) in December 2009. The first two tournaments were co-hosted by Universiti Kuala Lumpur (UNIKL).

WUPID was the brainchild of Daniel Hasni Mustaffa, Saiful Amin Jalun and Muhammad Yunus Zakariah. They were all former debaters for UPM who took part at all possible levels of debating from the Malaysian nationals to the World Championship.

Other forms of debate

Online debating

With the increasing popularity and availability of the Internet, differing opinions arise frequently. Though they are often expressed via flaming and other forms of argumentation, which consist primarily of assertions, formalized debating websites do exist. The debate style varies from site to site, with local communities and cultures developing. Some sites promote a contentious atmosphere that can border on "flaming" (the personal insult of your opponent, also known as a type of ad hominem fallacy), while others strictly police such activities and strongly promote independent research and more structured arguments.

Rule sets on various sites usually serve to enforce or create the culture envisioned by the site's owner, or in some more open communities, the community itself. Policing post content, style, and structure combine with frequent use of "reward" systems (such as reputation, titles, and forum permissions) to promote activities seen as productive while discouraging unwelcomed actions. These cultures vary sufficiently that most styles can find a home. Some online debate communities and forums practice Policy Debate through uploaded speeches and preset word counts to represent time limits present in physical debate.[42] These virtual debates typically feature long periods of theoretical prep time, as well as the ability to research during a round.

Originally most debate sites were little more than online or bulletin boards. Since then site-specific development has become increasingly common in facilitating different debate styles.

Debate shows

Debates have also been made into a television show genre.

See also

- International high-school debating

- Heart of Europe Debating Tournament

- World Individual Debating and Public Speaking Championships

- World Schools Debating Championships

- National High School Debate League of China

- International university debating

- Debate camp#Popular camps/institutes

- Australasian Intervarsity Debating Championships

- American Parliamentary Debate Association

- Canadian University Society for Intercollegiate Debate

- International Public Debate Association

- National Association of Urban Debate Leagues

- North American Debating Championship

- North American Public Speaking Championship

- World Universities Debating Championship

- World Universities Debating Championship in Spanish

References

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (January 2009) |

- ^ The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 4th ed., 1993 pg. 603.

- ^ Rodger, D; Stewart-Lord, A (2019). "Students' perceptions of debating as a learning strategy: A qualitative study". Nurse Education in Practice. 42: 102681. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2019.102681. PMID 31805450. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ Al-Mahrooqi & Tabakow, R. & M. "Effectiveness of Debate in ESL/EFL-Context Courses in the Arabian Gulf: A Comparison of Two Recent Student-Centered Studies in Oman and in Dubai, U.A.E." (PDF). 21st Century Academic Forum. 21st Century Academic Forum. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ^ Mary Thale, "London Debating Societies in the 1790s," The Historical Journal 32, no. 1 (March 1989): 58-9.

- ^ James Van Horn Melton, The Rise of the Public in Enlightenment Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

- ^ Thomas Munck, The Enlightenment: A Comparative Social History 1721–1794 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000).

- ^ Donna T. Andrew, "Popular Culture and Public Debate" in The Historical Journal, Vol. 39, Issue 02 (Cambridge University Press, June 1996), p. 406.

- ^ Goring, The Rhetoric of Sensibility in Eighteenth-Century Culture, 63.

- ^ Goring, The Rhetoric of Sensibility in Eighteenth-Century Culture, 65-6.

- ^ a b Andrew, "Popular Culture and Public Debate," 409.

- ^ Andrew, London Debating Societies, 82.

- ^ Andrew, Introduction to London Debating Societies, ix; Thale, "London Debating Societies in the 1790s," 59; Munck, The Enlightenment, 72.

- ^ Thale, "London Debating Societies in the 1790s," 60.

- ^ History of the Union | The Cambridge Union Society Archived 2013-12-24 at the Wayback Machine. Cus.org. Retrieved on 2013-07-15.

- ^ "Special Debates – Emergency Debates". www.parl.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 2017-02-12. Retrieved 2017-02-12.

- ^ "Emergency debates". UK Parliament. Archived from the original on 2016-11-15. Retrieved 2017-02-12.

- ^ Neuman, Nancy M. (October 2, 1988). "League Refuses to "Help Perpetrate a Fraud"". Press release. League of Women Voters. Archived from the original on August 23, 2012. Retrieved 2012-07-26.

- ^ "What Is Debating?". Cambridge Union Society. Archived from the original on 2015-08-14. Retrieved 2015-08-20.

Typically, judges decide how persuasive debaters have been through three key criteria: Content: What we say and the arguments and examples we use. Style: How we say it and the language and voice we use. Strategy: How well we engage with the topic, respond to other people's arguments and structure what we say.

- ^ "Inter-college debate contest". The Times of India. 2010-09-29. Retrieved 2011-12-10.

- ^ "Debaters Association of Victoria – Introduction to debating – Speaker roles". Debating Association of Victoria. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ "School Debating". Debating Association of Victoria. Debating Association of Victoria. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ "2012/04 Square Debate on European Energy Supply". fb-connections.org. Archived from the original on 2014-08-13.

- ^ "2011/04 Square Debate on European Defence". fb-connections.org. Archived from the original on 2014-08-13.

- ^ "Comparative Project". fb-connections.org. Archived from the original on 2014-10-20.

- ^ a b "French Debating Association". frenchdebatingassociation.fr. Archived from the original on 2012-04-02.

- ^ "national-forensic-journal – National Forensic Association". nationalforensics.org. Archived from the original on 2013-12-04.

- ^ "Regeln & Formate". VDCH. Archived from the original on 2013-08-23.

- ^ "Clubs vor Ort". VDCH. Archived from the original on 2014-08-25.

- ^ "The English-Speaking Union". britishdebate.com. Archived from the original on 2011-05-30.

- ^ "the Oxford Union – Forms of the House in Debate". oxford-union.org. Archived from the original on 2011-09-30.

- ^ "College Compass" (PDF). collegecompass.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-11-04.

- ^ "Paris-style debating – French Debating Association". frenchdebatingassociation.fr. Archived from the original on 2014-08-14.

- ^ "APDAWeb – Home". apdaweb.org. Archived from the original on 2017-12-15.

- ^ "Brazilian Institute of Debates". ibdebates.org. Archived from the original on 2016-08-07.

- ^ "The UFC Debate Society". SdDUFC. Archived from the original on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ "The UFRN Debate Society". Centro Acadêmico Amaro Cavalcanti. Archived from the original on 13 October 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ "Parli Brasil". Parli Brasil. Archived from the original on 7 August 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ "UFSC Debate Society". UFSC. Archived from the original on 14 September 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ "UFRJ Debate Society". SdDUFRJ. Archived from the original on 14 September 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ "2007-2008 Oregon School Activities Association Speech Handbook" (PDF). osaa.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-11.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-07-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Standard Rules and How-To". Archived from the original on 5 January 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2012.