Serpula

| Serpula Temporal range: Cretaceous – Recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Calcareous tubeworm, Serpula vermicularis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Serpula |

| Species and subspecies | |

|

29, see text. | |

Serpula (also known as calcareous tubeworm, serpulid tubeworm, fanworm, or plume worm) is a genus of sessile, marine annelid tube worms that belongs to the family Serpulidae.[3] Serpulid worms are very similar to tube worms of the closely related sabellid family, except that the former possess a cartilaginous operculum that occludes the entrance to their protective tube after the animal has withdrawn into it. The most distinctive feature of worms of the genus Serpula is their colorful fan-shaped "crown". The crown, used by these animals for respiration and alimentation,[3] is the structure that is most commonly seen by scuba divers and other casual observers.

Taxonomy

Following is a brief description of the cladistics and taxonomic classification of Serpula:

- Higher taxonomic ranks

- The genus Serpula belongs to the family Serpulidae, also known as serpulid worms or tubeworms.

- Family Serpulidae is one of 31 described families of the order Canalipalpata, also known as bristle-footed annelids or fan-head worms. In addition to the Serpulidae, the Canalipalpata also includes the fanworms (Sabellidae) and a family of deep-sea worms associated with hydrothermal vents (Alvinellidae).

- Order Canalipalpata belongs to the class Polychaeta, also known as bristle worms. There are more than 10,000 described species of polychaetes; they can be found in nearly every marine environment. Some species live in the coldest ocean temperatures of the abyssal plain, while others can be found in the extremely hot waters adjacent to hydrothermal vents. Polychaetes occur throughout the Earth's oceans at all depths, from forms that live as plankton near the surface, to a 2–3 cm specimen (still unclassified) observed by the robot ocean probe Nereus at the bottom of the Challenger Deep, the deepest spot in the Earth's oceans.[4][5][6][7]

- Class Polychaeta belongs to the phylum Annelida, also called ringed worms. There are over 17,000 living annelid species,[8] ranging in size from microscopic to the Australian giant Gippsland earthworm, which can grow up to 3 metres (9.8 ft) long.[9][10]

Species of Serpula

While the higher taxonomy is fairly well understood, the lower taxonomy within the genus Serpula is somewhat confusing, and not yet thoroughly worked out. Earlier sources have described as many as 77 different species and subspecies.[11][12] However, there are currently only 29 recognized species in the genus Serpula. The number and names of these species may soon change as a result of an ongoing revision of the genus by taxonomists.[13]

- Serpula cavernicola (Fassari & Mollica, 1991), Messina, Italy

- Serpula columbiana (Johnson, 1901), Puget Sound, Washington

- Serpula concharum (Langerhans, 1880), Madeira, Mediterranean-Atlantic

- Serpula crenata (Ehlers, 1908), Zanzibar, Indo-West Pacific; bathyal

- Serpula granulosa (Marenzeller, 1885), Kagoshima and Enoshima, Japan, Indo-West Pacific

- Serpula hartmanae (Reish, 1968), Bikini, Indo-West Pacific

- Serpula indica (Parab & Gaikwad, 1989), India

- Serpula israelitica (Amoureux, 1976), Haifa, Levant Basin, Israel

- Serpula japonica (Imajima, 1979), Honshu, Japan; possibly Seychelles

- Serpula jukesii (Baird, 1865), Indo-West Pacific

- Serpula lobiancoi (Rioja, 1917), Mediterranean-Atlantic

- Serpula longituba (Imajima, 1979), Honshu, Japan

- Serpula maorica (Benham, 1927), New Zealand

- Serpula nanhaiensis (Sun & Yang, 2001), South China Sea

- Serpula narconensis (Baird, 1865), Narcon Island, Antarctica, subantarctic

- Serpula oshimae (Imajima & ten Hove, 1984), Indo-West Pacific

- Serpula pacifica (Uchida, 1978), Sabiura, Japan

- Serpula philippensis (McIntosh, 1885), Philippines; bathyal

- Serpula planorbis (Southward, 1963), Irish Sea; bathyal

- Serpula rubens (Straughan, 1967), Queensland, New South Wales, Australia

- Serpula sinica (Wu & Chen, 1979), South China Sea

- Serpula tetratropia (Imajima & ten Hove, 1984), Palau and Caroline Island[14]

- Serpula uschakovi (Kupriyanova, 1999), Gilderbrandt Island, Sea of Japan

- Serpula vasifera (Haswell, 1885), Port Jackson, New South Wales, Australia

- Serpula vermicularis (Linnaeus, 1767), Western Europe

- Serpula vittata (Augener, 1914), Shark Bay, Western Australia; Indo-West Pacific

- Serpula watsoni (Willey, 1905), Trincomalee, Sri Lanka; Indo-West Pacific

- Serpula willeyi (Pillai, 1971), Sri Lanka

- Serpula zelandica (Baird, 1865), New Zealand

Geographic distribution, evolution, and habitat

Worldwide, very common. Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian oceans, Mediterranean Sea, North Sea, Red Sea. Species of the genus Serpula are common on the west coast of North America from Alaska to Baja California, but are rarely if ever found on the east coast of the United States. They are common in Europe and Africa.[12][15][16][17]

Like most tube-building polychaetes, worms of the genus Serpula are benthic, sedentary suspension feeders. They secrete and inhabit a permanent calcareous tube attached to hard substrata. As they do not travel outside their tubes, these worms do not have any specialized appendages for swimming.

Worms of the genus Serpula are commonly found attached to submerged rocks, shells, and even boats in many coastal areas around the world. They are found at depths ranging from intertidal to at least 800 meters.[16][18][19] Predators include predatory starfish such as the Ochre Sea Star (Pisaster ochraceous).[16]

Serpula has lived since the Cretaceous period, according to fossils found in the Cretaceous Black Creek Formation of North Carolina.[20]

Anatomy

Head

The funnel-shaped, symmetrical peristomium is fused with the prostomium to form the head, at the anterior end of the body. Worms of the genus Serpula have two photoreceptors or "eyespots" on the peristomium.[16][21] The prostomium bears a branchial "crown", a specialized mouth appendage which resembles a fan (for which the animals are given the name fanworms).

This crown, which can be extended for feeding and gas exchange, and rapidly retracted when threatened, consists of two bundles (one right and one left) of featherlike 'gills', known as branchiae or radioles. Each of these bundles consists of a single row of radioles attached to a branchial stalk and curved into a semicircle. These two semicircles form the funnel-shaped branchial crown. The mouth is at the apex of the funnel between the two branchial stalks.

When extended, these heavily ciliated radioles trap particles of organic matter and transport it towards the mouth. While they are primarily feeding structures, the radioles also serve as respiratory organs.[3][22][23] The radioles of different Serpula species are typically red, pink, or orange in color, with white transverse bands. Astaxanthin, a carotenoid pigment, is responsible for the bright red color of the crown of S. vermicularis.[24] There are usually about 40 radioles in an adult.

One of these radioles, called an operculum, is a highly specialized structure located on the dorsal part of the head. The operculum consists of a long, thick stalk with a cartilaginous, cone-shaped plug at the distal end.[25] This plug can be used to seal the opening of the tube after the animal has retreated inside. The operculum, which is usually red in color, secretes a mucus which seems to possess antibiotic properties. It is not unusual for the animal to have two opercula. Both serpulid and sabellid worms have radioles, but sabellids (such as Sabella pavonina) lack an operculum.[26]

A single median nephridiopore is located dorsally on the head, between the upper lip and a median dorsal papilla. The anterior end of the fecal groove passes over it and urine is released from it into the waste current. Like all serpulids and sabellids, they have only a single pair of metanephridia, which empty via this nephridiopore.[3]

Thorax

The thoracic region of the body consists of seven chaetigers (segments bearing chaetae). Chaetae are small appendages that aid the worm with mobility. The first of these segments is the collar segment (peristomium), to which the prostomium is attached. The peristomium bears an elaborate, delicate, membranous collar that overlaps the margins of the aperture of the tube and covers the opening of the tube when the head is extended.

There is a pair of calcium-secreting glands located near the midventral line on the posterior end of the peristomium. These glands open onto the "ventral shields", which are wide glandular pads on the ventral side of the anterior thoracic segments. The ventral shields secrete organic material and use this, combined with the calcium secreted by the glands, to form a paste from which the tube is made.

These white calcareous tubes are made of both calcite and aragonite.[24] They are usually smooth with faint longitudinal ridges, curved but not strongly coiled, and are rarely more than 12 cm in length. The tube appears to be shaped by the ventral shields and by a collar which is just behind the head.

There is a median, longitudinal, ciliated, thoracic fecal groove on the dorsal midline of the thorax. It is a broad, shallow, relatively indistinct trough running the length of the thorax and ending at the head.[3]

Abdomen

Worms of the genus Serpula have a distinct abdominal region, composed of up to 190 very short, wide segments. The terminal body region is the tiny pygidium, on which the anus is located. A fecal groove extends the length of the ventral midline of the abdomen. The fecal groove spirals across to the dorsal position as it reaches the thoracic region.

Vertical ciliary tracts in the grooves between adjacent abdominal segments move particles toward the abdominal fecal groove. Once in the abdominal fecal groove, further ciliary currents transport particulate matter (feces, gametes, etc.) from the depths of the tube, through the thoracic segment to the aperture where it can be released to the sea.[3][27]

Physiology

Circulatory system

Vasculature

Worms of the genus Serpula have a very unusual dual circulatory system, consisting of a central system of large vessels through which a continuous true circulation of blood is maintained, and also a peripheral system of small, predominantly blind-ending vessels which alternately empty and fill in a tidal fashion.[28][29]

In the central circulatory system, the blood moves anteriorly from the tip of the abdomen to the front of the thorax through a sinus enveloping the alimentary canal, and posteriorly through a ventral blood vessel. The ventral vessel and the sinus communicate with each other by segmentally arranged ring vessels, and by a dorsal vessel, a transverse vessel, and a pair of circumesophageal vessels situated at the anterior end of the thorax.[28][29] The dorsal vessel in some of the larger serpulids, like Serpula, possesses a valve and a muscular sphincter, probably to prevent backflow of blood from the transverse vessel.[28]

The blood circulation in the periphery, especially the radiole, is especially unusual. Instead of venous and arterial blood flowing through afferent and efferent vessels within the radiole, there is a single branchial sinus through which blood flows in both directions, in a tidal fashion. The vessels of the peripheral system receive their blood from the central system, returning it back along the same channels (i.e., these channels serve in both afferent and efferent directions).[28]

The peripheral circulatory system has the following components: the two branchial vessels and their branches in the crown; the periesophageal vascular plexuses; the vessels of the collar and lips; the vessels supplying the body wall, thoracic membrane, and parapodia. The single vessels in each radiole of the branchial crown, and the vessels of opercula, are all branches of the two branchial vessels.[28]

When the crown is retracted inside the tube, the radioles and operculum cease to function as a respiratory organ. The movement of blood in the capillaries of the thoracic membrane and body wall continues, however. Under these circumstances, respiratory exchange is probably carried out between the blood in these vessels and the surrounding water, which is kept moving through the tube by vigorous pumping movements of the abdomen and also by the activity of the ciliary tracts.[28]

Oxygen transport mechanisms

The well-developed longitudinal muscles of the body wall of serpulids lack a special blood supply. The body surface in the larger serpulids, like Serpula, has a rich blood supply, and the water in contact with this surface is constantly renewed. It seems probable that the outer body surface of serpulids serves as a respiratory membrane, supplying oxygen to the underlying muscles by diffusion.[29]

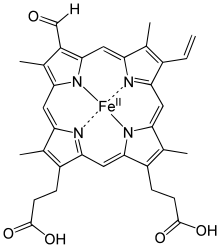

The biochemistry of the blood of Serpula is especially unusual in that the blood contains not only hemoglobin, but also chlorocruorin. While all sabellids and serpulids employ chlorocruorin as an oxygen transport macromolecule,[30][31][32] Serpula is the only genus that appears to possess both hemoglobin as well as chlorocruorin.[33]

Chlorocruorin is an oxygen-binding hemeprotein whose affinity for oxygen is weaker than that of most hemoglobins. A dichromatic compound, chlorocruorin is noted for appearing green in dilute solutions, though it appears light red when found in concentrated solutions.[33][34][35] Its structure is very similar to erythrocruorin, each molecule being composed of more than a hundred interlinked 16-17kDa myoglobin-like subunits arranged in a giant complex with a total weight exceeding 3600kDa. This enormous macromolecule is free floating in the plasma, and not contained within red blood cells.[36][37]

The ratio of plasma hemoglobin to chlorocruorin is high in younger individuals, but this ratio reverses as the animal matures.[33] Presumably this reflects a lower oxygen consumption in the adult worm, relative to the juveniles.

Nervous system

Like other annelids, these worms possess well-developed nervous systems. The nervous system consists of a central brain in the upper part of the head, which is relatively large compared with that of other annelids. Extending from the brain is a large ventral nerve cord running the length of the body. There are many supporting ganglia along the length of this cord (including pleural, pedal and cerebral ganglia), and a series of small nerves in each body segment. Signals transmitted through the pedal ganglia allow the worms to retract rapidly into their tube if threatened.

Reproductive system

Sexes are separate. Like other annelids, the coelom stores and provides nutrients for gametes.[38] When they reproduce, they simply shed their gametes straight into the water where the ova and spermatozoa become part of the zooplankton and are carried by the currents to new sites, where the juvenile worms settle into the substrate. Length of the planktonic stage is unknown but comparison with other serpulids suggests it may be between six days and two months, although in other species the period has been shown to vary with season, salinity or food availability, and delayed settling may cause reduced discrimination of substrata during settling (see ten Hove, 1979 for additional references).

Digestive system

Worms of the genus Serpula are filter feeders, and possess a complete digestive system. Like other polychaetes, Serpula excrete with fully developed nephridia.[25]

Gallery

-

Serpula vermicularis (Calcareous tubeworm)

-

Serpula vermicularis (Calcareous tubeworm)

-

Serpula vermicularis (Calcareous tubeworm)

Click here to see more photographs of various specimens of the genus Serpula.

See also

References

- ^ Carl von Linné (Carolus Linnaeus) (1758). Systema naturae. Per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. 10th Edition. Volume 1. Holmiæ: Impensis Laurentii Salvii. p. 786. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ "Serpula". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f Richard S. Fox (4 July 2006). "Serpula vermicularis". Invertebrate Anatomy OnLine. Lander University. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ^ John Roach (2005). "Life Is Found Thriving at Ocean's Deepest Point". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ website of the government of Guam: Geography of Guam. Accessed 3 May 2010.

- ^ Lonny Lippsett; Amy E. Nevala (2009). "Nereus Soars to the Ocean's Deepest Trench". Oceanus Magazine, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ WHOI Media Relations (2009). "Hybrid Remotely Operated Vehicle "Nereus" Reaches Deepest Part of the Ocean". Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ Rouse GW (2002). "Annelida (Segmented Worms)". Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1038/npg.els.0001599. ISBN 978-0470016176.

- ^ Ruppert EE; Fox RS; Barnes RD (2004). "Annelida". Invertebrate Zoology (7 ed.). Brooks/Cole. pp. 414–420. ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1.

- ^ Lavelle, P (1996). "Diversity of Soil Fauna and Ecosystem Function" (PDF). Biology International. 33. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ ZipcodeZoo.com: Genus Serpula Archived 30 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 1 May 2010.

- ^ a b Appeltans W, Bouchet P, Boxshall GA, Fauchald K, Gordon DP, Hoeksema BW, Poore GCB, van Soest RWM, Stöhr S, Walter TC, Costello MJ. (eds) (2010). World Register of Marine Species: WoRMS Taxon list for Genus Serpula. Accessed 1 May 2010.

- ^ Harry A. ten Hove; Elena Kupriyanova (2009). Zootaxa 2036: Taxonomy of Serpulidae (Annelida, Polychaeta): The state of affairs (PDF). Auckland, New Zealand: Magnolia Press. pp. 93–95. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ P.A. Hutchings, ed. (1984). "Harry A. ten Hove (1984). Towards a phylogeny in serpulids (Annelida; Polychaeta)". Proceedings of the first International Polychaete Conference. Sydney: The Linnean Society of New South Wales. pp. 181–196. ISBN 978-0-9590535-0-0.

- ^ James H. McLean (1962). "Sublittoral ecology of kelp beds of the open coast area near Carme, California" (PDF). The Biological Bulletin. 122 (1): 95–114. doi:10.2307/1539325. JSTOR 1539325. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ a b c d Department of Biology, Walla Walla University: Serpula vermicularis Archived 2 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Rosario Beach Marine Laboratory. Accessed 1 May 2010.

- ^ Colin G. Moore; Graham R. Saunders; Dan B. Harries (1998). "The status and ecology of reefs of Serpula vermicularis (Polychaeta: Serpulidae) in Scotland". Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. 8 (5): 645–656. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0755(199809/10)8:5<645::AID-AQC295>3.0.CO;2-G. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ Nicola D. Chapman, Colin G. Moore, Dan B. Harries and Alastair R. Lyndon (July 2007). "Recruitment patterns of Serpula vermicularis L. (Polychaeta, Serpulidae) in Loch Creran, Scotland". Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 73 (3–4): 598–606. Bibcode:2007ECSS...73..598C. doi:10.1016/j.ecss.2007.03.001.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wolf E. Arntz and Julian Gutt (eds) (1999). "M. C. Gambi (1999). Preliminary Observations on Distribution, Biology and Feeding Ecology of some Suspension Feeding Polychaetes in the Eastern Weddell Sea." (PDF). The Expedition ANTARKTIS W 3 (E ASIZ 11) of RV Polarstern in 1998. Ber. Polarforsch. pp. 83–94. ISSN 0176-5027. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help);|journal=ignored (help) - ^ "Online Collections | North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences". collections.naturalsciences.org. Archived from the original on 16 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ Fan Worms & Feather Dusters (Annelids). Accessed 1 May 2010.

- ^ An Underwater Field Guide to Point Lobos: Invertebrates: Worms. Accessed 1 May 2010.

- ^ G. P. Wells (1952). "The Respiratory Significance of the Crown in the Polychaete Worms Sabella and Myxicola". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 140 (898): 70–82. Bibcode:1952RSPSB.140...70W. doi:10.1098/rspb.1952.0045. JSTOR 82713. PMID 13003913. S2CID 36440648.

- ^ a b Pamela L. Beesley, Graham J. B. Ross, Christopher J. Glasby (eds) (2000). "Gregory W. Rouse (2000). Family Serpulidae.". Polychaetes & allies: the southern synthesis, Volume 4, Part 1. Melbourne, Australia: CSIRO Publishing Australia. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-643-06571-0. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Jean Hanson (1949). "Observations on the Branchial Crown of the Serpulidae (Annelida, Polychaeta)". Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science. 90 (s3): 221–233. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ Ruppert, Edward E.; Fox, Richard S. (1988). "Annelida: Segmented Worms". Seashore animals of the Southeast: a guide to common shallow-water invertebrates of the southeastern Atlantic Coast. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-87249-535-7. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ Edward E. Ruppert; Richard S. Fox; Robert D. Barnes (2003). Invertebrate Zoology: A Functional Evolutionary Approach (7 ed.). Pacific Grove, California: Brooks Cole. ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1.

- ^ a b c d e f Jean Hanson (1950). "The blood-system in the Serpulimorpha (Annelida, Polychaeta): I. The anatomy of the blood-system in the Serpulidae". Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science. 91 (2): 111–129. PMID 24538989. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ a b c Jean Hanson (December 1950). "The Blood-system in the Serpulimorpha (Annelida, Polychaeta): II. The Anatomy of the Blood-system in the Sabellidae, and Comparison of Sabellidae and Serpulidae" (PDF). Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science. 91 (4): 369–378. PMID 24540162. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ H. Munro Fox (1933). "The Blood Circulation of Animals Possessing Chlorocruorin". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 112 (779): 479–495. doi:10.1098/rspb.1938.0042. JSTOR 81599.

- ^ R. F. Ewer; H. Munro Fox (1940). "On the Function of Chlorocruorin". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 129 (855): 137–153. Bibcode:1940RSPSB.129..137E. doi:10.1098/rspb.1940.0033. JSTOR 82389.

- ^ D.W. Ewer (1941). "The blood systems of Sabella and Spirographis". Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science. 82 (s2): 587–619. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ a b c H. Munro Fox (1949). "On Chlorocruorin and Haemoglobin". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 136 (884): 378–388. Bibcode:1949RSPSB.136..378F. doi:10.1098/rspb.1949.0031. JSTOR 82565. PMID 18143368. S2CID 6133526.

- ^ H. Munro Fox (1926). "Chlorocruorin: A Pigment Allied to Haemoglobin". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 99 (696): 199–220. doi:10.1098/rspb.1926.0008. JSTOR 81088.

- ^ H.Munro Fox (1932). "The Oxygen Affinity of Chlorocruorin". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 111 (772): 356–363. doi:10.1098/rspb.1932.0060. JSTOR 81716.

- ^ Lamy JN; Green BN; Toulmond A; Wall JS; Weber RE; Vinogradov SN (1996). "Giant Hexagonal Bilayer Hemoglobins". Chem Rev. 96 (8): 3113–3124. doi:10.1021/cr9600058. PMID 11848854.

- ^ Pallavicini A, Negrisolo E, Barbato R, et al. (July 2001). "The primary structure of globin and linker chains from the chlorocruorin of the polychaete Sabella spallanzanii". J. Biol. Chem. 276 (28): 26384–90. doi:10.1074/jbc.M006939200. PMID 11294828.

- ^ Ruppert & Fox 1988, p. 310.

External links

- Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research: Polychaete Families of Singapore: Serpulidae

- Annelida.net: About Family Serpulidae polychaetes in New Zealand. Accessed 1 May 2010.

- Chamberlin, Ralph V. 1920. The Polychaetes Collected by the Canadian Arctic Expedition, 1913–18. Report of the Canadian Arctic Expedition 9. Annelids, parasitic worms, Protozoans, etc. (B. Polychaeta): 1-41. Pl.1-6. Thomas Mulvey. Ottawa.

- Hartmann-Schröder, G. (1996). Annelida, Borstenwürmer, Polychaeta [Annelida, bristleworms, Polychaeta]. 2nd revised ed. The fauna of Germany and adjacent seas with their characteristics and ecology, 58. Gustav Fischer: Jena, Germany. ISBN 3-437-35038-2. 648 pp. (look up in IMIS)