Battle of P'ohang-dong

| Battle of P'ohang-dong | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of Pusan Perimeter | |||||||

South Korean troops march toward the front lines of the Pusan Perimeter | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 58,000 (est.) | 21,500 (est.) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

~3800 killed 181 captured | |||||||

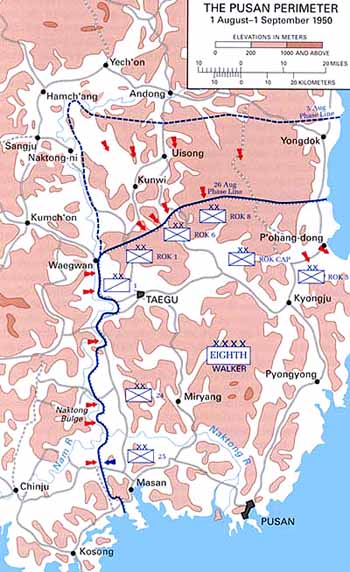

The Battle of P'ohang-dong was an engagement between the United Nations Command (UN) and North Korean forces early in the Korean War, with fighting continuing from 5–20 August 1950 around the town of P'ohang-dong, South Korea. It was a part of the Battle of Pusan Perimeter, and was one of several large engagements fought simultaneously. The battle ended in a victory for the UN after their forces were able to drive off an attempted offensive by three North Korean Korean People's Army (KPA) divisions in the mountainous eastern coast of the country.

Forces of the South Korean Republic of Korea Army (ROKA), supported by the United States Navy and United States Air Force (USAF), defended the eastern coast of the country as a part of the Pusan Perimeter. When several divisions of the KPA crossed through mountainous terrain to push the UN forces back, a complicated battle ensued in the rugged terrain around P'ohang-dong, which contained the vital supply line to the main UN force at Taegu.

For two weeks KPA and ROK units fought in several bloody back-and-forth battles, taking and retaking ground in which neither side was able to gain the upper hand. Finally, following the breakdown of the KPA supply lines and amidst mounting casualties, the exhausted North Korean troops were forced to retreat.

The battle was a turning point in the war for KPA forces, which had seen previous victories owing to superior numbers and equipment, but the distances and demands exacted on them at P'ohang-dong rendered their supply lines untenable.

Background

Outbreak of war

Following the invasion of South Korea by North Korea and the subsequent outbreak of the Korean War on 25 June 1950, the United Nations decided to enter the conflict on behalf of South Korea. The United States subsequently committed ground forces to the Korean peninsula with the goal of fighting back the North Korean invasion and to prevent South Korea from collapsing. However, US forces in the Far East had been steadily decreasing since the end of World War II five years earlier, and at the time the closest forces were the US 24th Infantry Division, headquartered in Japan.[1][2]

Advance elements of the 24th Division were badly defeated in the Battle of Osan on 5 July, the first encounter between US and KPA forces.[3] For the first month after the defeat of Task Force Smith, 24th Division was repeatedly defeated and forced south by superior KPA numbers and equipment.[4][5] The regiments of the 24th Division were systematically pushed south in engagements around Chochiwon, Chonan and Pyongtaek.[4] The 24th Division made a final stand in the Battle of Taejon, where it was almost completely destroyed but delayed KPA forces until July 20.[6] By that time the 8th Army's force of combat troops were roughly equal to KPA forces attacking the region, with new UN units arriving every day.[7]

While the 24th Infantry Division was fighting on the Korean western front, the KPA 5th and 12th Infantry Divisions advanced steadily on the eastern front.[8] The KPA, 89,000 men strong, had advanced into South Korea in six columns, catching the ROK by surprise, resulting in a complete rout. The smaller ROK suffered from widespread lack of organization and equipment, and it was unprepared for war.[9] Numerically superior, KPA forces destroyed isolated resistance from the 38,000 ROK soldiers on the front before it began moving steadily south.[10]

North Korean advance

With Taejon captured, KPA forces began surrounding the Pusan Perimeter from all sides in an attempt to envelop it. The KPA 4th and 6th Infantry Divisions advanced south in a wide flanking maneuver. The two divisions attempted to envelop the UN's left flank, but became extremely spread out in the process.[11] At the same time the KPA 5th and 12th Divisions pressured the ROK on the right flank.[12] They advanced on UN positions with armor and superior numbers, repeatedly defeating UN forces and forcing them further south.[11] On 21 July the KPA 12th Division was ordered by KPA II Corps to capture P'ohang-dong by 26 July.[13]

Though they were steadily pushed back, ROK forces on the right flank increased their resistance further south, hoping to delay KPA units as much as possible. KPA and ROK units sparred for control of several cities, inflicting heavy casualties on one another. The ROK forces defended Yongdok fiercely before being pushed back. They also performed well in the Battle of Andong, forcing the KPA 12th Division to delay its attacks on P'ohang-dong until early August.[14][15] The ROK had also undergone significant reorganization, and after receiving a large number of recruits by 26 July, the ROK had reached an effective strength of 85,871 men.[16]

Eastern corridor

Along the ROK front of the perimeter, on the eastern corridor, the terrain made moving through the area incredibly difficult. A major road ran from Taegu 50 mi (80 km) east to P'ohang-dong on Korea's east coast. The only major north-south road intersecting this line moves south from Andong through Yongch'on, midway between Taegu and P'ohang-dong.[17]

The only other natural entry through the line lies at the town of An'gang-ni, 12 mi (19 km) west of P'ohang-dong, which is situated near a valley through the natural rugged terrain to the major rail hub of Kyongju, which was a staging area for moving supplies to Taegu.[17] Gen.Walton Walker—commanding the Eighth United States Army—chose not to heavily reinforce the area, as he felt the terrain made meaningful attack impossible, preferring to respond to attack with reinforcements from the transportation routes and air cover from Yonil Airfield, which was south of P'ohang-dong.[18]

With the exception of the valley between Taegu and P'ohong-dong, the terrain along the line was extremely rough and mountainous thanks to the Taebaek Mountains, which ran from north to south down Korea's east coast. Northeast of P'ohong-dong along the South Korean line the terrain was especially treacherous, and movement in the region was extremely difficult. Thus, the UN established the northern line of the Pusan Perimeter using the terrain as a natural defense.[19] However, the rough terrain also made communication difficult, particularly for the ROK forces.[20]

Prelude

The ROK Army—a force of 58,000—[21] was organized into two corps and five divisions along the line; from east to west, I Corps controlled the 8th Infantry Division and Capital Divisions, while the II Corps controlled the 1st Division and 6th Infantry Division. A reconstituted 3rd Division was placed under direct ROK Army control.[19][22] Morale among the UN units was low due to the large number of defeats at that point in the war.[20][23] The ROK Army had lost an estimated 70,000 men up to that point.[24][25]

At the same time forces of the US 5th Air Force supplied 45 P-51 Mustang fighters to provide cover from Yonil Airfield, and the US Navy had several ships providing support by sea.[26] Evacuation of wounded and surrounded troops was carried out by the aircraft carriers USS Valley Forge and Philippine Sea. The heavy cruisers USS Helena and Toledo also provided fire support for troops operating in the town.[27]

The KPA troops were organized into a mechanized combined arms force of ten divisions, originally numbering some 90,000 well-trained and well-equipped men, in July, with hundreds of T-34 tanks.[28] However, defensive actions by UN forces had delayed the KPA significantly in their invasion of South Korea, costing them 58,000 casualties and the destruction of a large number of tanks.[29] In order to recoup these losses, the North Koreans had to rely on less experienced replacements and conscripts, many of whom had been taken from the conquered regions of South Korea.[30]

The KPA forces suffered from a shortage of men and equipment; their divisions were far understrength.[25][31] Opposing the ROK, from west to east, were the 8th, 12th, and 5th Divisions and the 766th Independent Infantry Regiment.[20] On 5 August the 8th Division was estimated to have 8,000 men, the 5th Division had 6,000, the 12th Division had 6,000 and the 766th Independent Regiment had 1,500, giving these units a total strength of at least 21,500.[31]

Battle

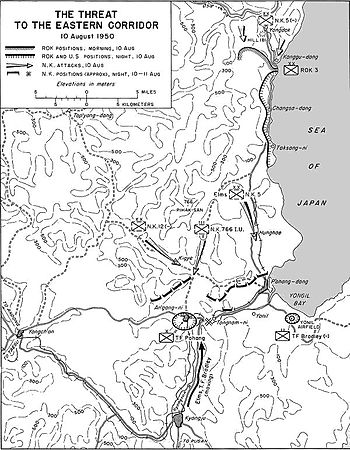

In early August the three KPA divisions mounted offensives against the three passes through the ROK line. The 8th Division attacked Yongch'on, the 12th Division attacked P'ohang-dong and the 5th Division, in conjunction with the 766th Independent Infantry Regiment, attacked toward An'gang-ni at Kigye, 6 mi (9.7 km) north of the town.[17] The ROK forces had far less training and were poorly equipped, so they presented the weakest line on the Pusan Perimeter. The North Koreans knew they could be most successful there.[32]

Opening moves

The KPA 8th Division's attack stalled almost immediately. The division drove for Yongch'on from Uiseong. However, the attack failed to reach the Taegu-P'ohang corridor after being surprised and outflanked by the ROKA 8th Division. The 8th Division's 3rd Regiment was nearly destroyed by ROKA forces immediately, forcing its 2nd Regiment to attempt to relieve it, resulting in at least 700 casualties for the 2nd Regiment. At least six tanks were also destroyed by USAF F-51 Mustangs and mines.[33]

This fighting was so heavy that the KPA 8th Division was forced to hold its ground a week before trying to advance. When it finally broke out, it was only able to advance briefly before it was stalled again by ROKA resistance. The division was forced to halt a second time to wait for reinforcements.[33] However, the other two attacks were more successful, catching the UN forces by surprise.[17] The KPA quickly pushed ROKA forces back.[34]

East of the KPA and ROKA 8th Divisions, the KPA 12th Division crossed the Naktong River at Andong, moving through the mountains in small groups to reach P'ohang-dong.[27] The division was far under strength and at least one of its artillery batteries had to send its guns back north because it had no ammunition for them.[33] UN planners had not anticipated that the 12th Division would be able to do this effectively, and thus were unprepared when its forces infiltrated the region so heavily.[35]

On 9 August troops from the ROKA 25th Regiment, Capital Division, probed through the mountains from Kigye to establish contact with the ROKA 3rd Division south of Yongdok. It advanced 2.5 mi (4.0 km) north before encountering fierce KPA resistance, which pushed it almost 5 mi (8.0 km) south. It was apparent to the UN forces that the ROKA 3rd Division was being outflanked. It held the road 20 mi (32 km) north of P'ohang-dong but there were no defenses inland in the mountains and KPA units had penetrated there.[33]

In the meantime, the ROKA 3rd Division was heavily engaged with the KPA 5th Division along the coastal road to P'ohang-dong. The divisions' clashes centered on the town of Yongdok, with each side capturing and recapturing the town several times. On 5 August the KPA launched their attack, again taking the town from the ROKA forces and pushing them south. At 19:30 on 6 August, the ROKA launched a counterattack to retake the hill.[36]

US aircraft and ships pounded the town with rockets, napalm and shells before ROKA troops from the 22nd and 23rd regiments swarmed the town. However, KPA 5th Division forces were able to infiltrate the coastal road south of Yongdok at Hunghae. This effectively surrounded the ROKA 3rd Division, trapping it several miles above P'ohang-dong.[36] The KPA 766th Independent Regiment advanced around the ROKA 3rd Division and took the area around P'ohang-dong.[37]

Due to severe manpower shortages, ROKA commanders had assigned a company of student volunteer soldiers to defend P'ohang-dong Girl's Middle School to delay the KPA advance into the town. On August 11 the squad held their ground and confronted the more numerous KPA forces. Out of an initial 71 squad members, 48 died in the 11-hour-long fight. This part of the battle is depicted in the movie 71: Into the Fire.[38]

UN counteroffensive

On 10 August Eighth Army organized Task Force P'ohang, consisting of the ROKA 17th, 25th and 26th Regiments as well as the ROKA 1st Anti-Guerrilla Battalion, Marine Battalion and a battery from the US 18th Field Artillery Battalion. The task force was given the mission to clear out KPA forces in the mountainous region.[39] At the same time the Eighth Army formed Task Force Bradley, consisting of elements of the 8th Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division under the command of Brig. Gen. Joseph S. Bradley, the 2nd Division's assistant commander.[40] Task Force Bradley was tasked with defending P'ohang-dong from the KPA 766th Independent Regiment, which was infiltrating the town.[37]

On 11 August Task Force Bradley struck out from Yonil Airfield to counterattack the KPA forces around P'ohang-dong while Task Force P'ohang attacked from An'gang-ni area. Both forces immediately met resistance from KPA units. By that time the KPA had captured P'ohang-dong.[41] What followed was a complicated series of fights through the large region around P'ohang-dong and An'gang-ni as ROKA forces, aided by US air power, engaged groups of KPA units operating all around the vicinity.[41]

The KPA 12th Division was operating in the valley west of P'ohang-dong and was able to push back Task Force P'ohang and the ROKA Capital Division. At the same time the KPA 766th Infantry Regiment and elements of the KPA 5th Division fought Task Force Bradley at and south of P'ohang-dong. US naval fire was able to drive KPA troops from the town, but it became a bitterly contested no man's land as fighting moved to the hills around the town.[41]

UN forces pull back

By 13 August KPA troops were operating in the mountains west and southwest of Yonil Airfield. USAF commanders—wary of enemy attack—evacuated the 45 P-51s of the 39th and 40th Fighter Squadrons from the airstrip, despite complaints from UN commander General Douglas MacArthur. However, the airstrip remained under the protection of UN ground forces and never came under direct KPA fire.[42] The squadrons were moved to Tsuiki on the island of Kyushu, Japan.[43][44]

As the battles at P'ohang-dong raged to the south, the ROK 3rd Division faced increasing pressure from the KPA 5th Division,[27] which continued to attack the ROK unit hoping it would collapse, and the KPA troops were able to slowly erode the ROK division's defenses, forcing it into a smaller and smaller pocket. The ROK 3rd Division was forced further south to the village of Changsa-dong, where US Navy planners began preparations to evacuate the division by LSTs and DUKWs.[44]

The division would sail 20 miles (32 km) south to Yonil Bay to join other UN forces in a coordinated attack to push the KPA out of the region.[26][43] This evacuation was carried out on the night of 16 August under heavy support from the US Navy.[27] In all, 9,000 men of the division were evacuated south, as well as 1,200 National Police and 1,000 laborers.[26] Now at the height of their advance, the KPA divisions had pushed the line to within 12 mi (19 km) of Taegu.[34]

North Korean defeat

By 14 August large forces from the KPA 5th and 12th Divisions, as well as the 766th Independent Regiment, were focused entirely on taking P'ohang-dong. However they were unable to hold it because of US air superiority and naval bombardment on the town.[26] More importantly, the supply chain had completely broken down for the division, and more food, ammunition and supplies were not available. Captured KPA prisoners claimed the units received no food after 12 August and had been so exhausted that they were completely unable to fight.[43][45] Opposing them were the ROK Capital Division and Task Forces P'ohang and Bradley which had joined forces to prepare for a final offensive to push the KPA out of the region.[46]

UN forces began their final counteroffensive against the stalled KPA on 15 August. Intense fighting around P'ohang-dong ensued for several days, as each side suffered extensive casualties in back-and-forth battles.[46] By 17 August UN forces were able to push KPA troops out of the Kyongju corridor and An'gang-ni, putting the supply road to Taegu out of immediate danger. The KPA 766th Independent Regiment—now down to 1,500 men—was forced to withdraw north to prevent being surrounded.[47]

The KPA 12th Division, also down to just 1,500, evacuated P'ohang-dong after this, having been exhausted from heavy casualties.[27] The two units merged and received replacements, with the KPA 12th Division re-forming with 5,000 men. By 19 August the KPA had completely withdrawn from the offensive and retreated into the mountains.[43][44] Troops of the ROK Capital Division advanced to 2 mi (3.2 km) north of Kigye, while the ROK 3rd Division retook P'ohang-dong and advanced north of the town the next day.[47] The ROK line had been pushed back several miles, but it had managed to repel the KPA.[44]

Aftermath

The fight at P'ohang-dong was the final breaking point for KPA units already on the verge of exhaustion from continuous combat. KPA supply lines were overextended to the point of breaking down, causing a collapse in resupply that is seen as a primary factor in turning the tide of the battle.[44][45] Moreover, US air superiority was also crucial to the engagement, since repeated attacks by US aircraft prevented the KPA from reaching and holding their objectives.[35]

Poor organization among both KPA and ROK units made it extremely difficult to estimate total casualties for both sides. Several units were completely destroyed in the fighting, making precise casualty counting difficult.[31] A memo from the ROK claimed 3,800 KPA killed and 181 captured in the P'ohang area from 17 August onward.[45] However, casualty numbers are likely far higher. The KPA 12th Division alone likely suffered at least 4,500 casualties on top of that number, reporting a strength of 6,000 on 5 August[31] and only 1,500 on 17 August.[47]

See also

References

Citations

- ^ Varhola 2000, p. 3

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 52

- ^ Catchpole 2001, p. 15

- ^ a b Varhola 2000, p. 4

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 90

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 105

- ^ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 103

- ^ Appleman 1998, pp. 104–105

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 1

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 2

- ^ a b Appleman 1998, p. 222

- ^ Appleman 1998, pp. 182–188

- ^ Appleman 1998, p. 187

- ^ Catchpole 2001, p. 22

- ^ Appleman 1998, p. 188

- ^ Appleman 1998, pp. 188, 190

- ^ a b c d Appleman 1998, p. 319

- ^ Appleman 1998, p. 320

- ^ a b Appleman 1998, p. 253

- ^ a b c Appleman 1998, p. 255

- ^ Catchpole 2001, p. 20

- ^ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 109

- ^ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 108

- ^ Appleman 1998, p. 262

- ^ a b Fehrenbach 2001, p. 113

- ^ a b c d Appleman 1998, p. 330

- ^ a b c d e Catchpole 2001, p. 27

- ^ Stewart 2005, p. 225

- ^ Stewart 2005, p. 226

- ^ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 116

- ^ a b c d Appleman 1998, p. 263

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 133

- ^ a b c d Appleman 1998, p. 321

- ^ a b Alexander 2003, p. 134

- ^ a b Fehrenbach 2001, p. 135

- ^ a b Appleman 1998, p. 324

- ^ a b Appleman 1998, p. 326

- ^ 강은나래 2011

- ^ Appleman 1998, p. 322

- ^ Appleman 1998, p. 325

- ^ a b c Appleman 1998, p. 327

- ^ Appleman 1998, p. 329

- ^ a b c d Fehrenbach 2001, p. 136

- ^ a b c d e Alexander 2003, p. 135

- ^ a b c Appleman 1998, p. 333

- ^ a b Appleman 1998, p. 331

- ^ a b c Appleman 1998, p. 332

Sources

- Alexander, Bevin (2003), Korea: The First War We Lost, Hippocrene Books, ISBN 978-0-7818-1019-7

- Appleman, Roy E. (1998), South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu: United States Army in the Korean War, Department of the Army, ISBN 978-0-16-001918-0, archived from the original on 2019-10-18, retrieved 2010-12-22

- Catchpole, Brian (2001), The Korean War, Robinson Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84119-413-4

- Ecker, Richard E. (2004), Battles of the Korean War: A Chronology, with Unit-by-Unit United States Casualty Figures & Medal of Honor Citations, McFarland & Company, ISBN 978-0-7864-1980-7

- Fehrenbach, T.R. (2001), This Kind of War: The Classic Korean War History – Fiftieth Anniversary Edition, Potomac Books Inc., ISBN 978-1-57488-334-3

- Gugeler, Russell A. (2005), Combat Actions in Korea, University Press of the Pacific, ISBN 978-1-4102-2451-4

- Stewart, Richard W. (2005), American Military History Volume II: The United States Army in a Global Era, 1917–2003, Department of the Army, ISBN 978-0-16-072541-8

- Varhola, Michael J. (2000), Fire and Ice: The Korean War, 1950–1953, Da Capo Press, ISBN 978-1-882810-44-4

- 강은나래 (2011-10-04), "<'포화 속으로' 학도병들..61년 만의 군번 수여식>", Yonhap News (in Korean), archived from the original on 2017-09-27, retrieved 2011-12-09

- Battles and operations of the Korean War in 1950

- Battles of the Korean War involving South Korea

- Battles of the Korean War involving North Korea

- Battle of Pusan Perimeter

- Battles of the Korean War

- Battles of the Korean War involving the United States

- History of North Gyeongsang Province

- August 1950 events in Asia

- Pohang