Cork Harbour

| Cork Harbour | |

|---|---|

Aerial view of lower Cork Harbour from Crosshaven (south/foreground) to Great Island | |

| |

| Location | Cork |

| Coordinates | 51°51′N 8°16′W / 51.850°N 8.267°W |

| River sources | River Lee |

| Ocean/sea sources | Celtic Sea |

| Basin countries | Ireland |

| Settlements | Cork |

| Designated | 7 June 1996 |

| Reference no. | 837[1] |

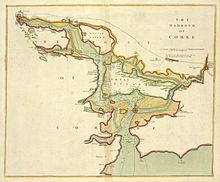

Cork Harbour (Irish: Cuan Chorcaí)[2] is a natural harbour and river estuary at the mouth of the River Lee in County Cork, Ireland. It is one of several which lay claim to the title of "second largest natural harbour in the world by navigational area" (after Port Jackson, Sydney).[3] Other contenders include Halifax Harbour in Canada, Trincomalee Harbour in Sri Lanka and Poole Harbour in England.

The harbour has been a working port and a strategic defensive hub for centuries, and it has been one of Ireland's major employment hubs since the early 1900s. Traditional heavy industries have waned since the late 20th century, with the likes of the closure of Irish Steel in Haulbowline and shipbuilding at Verolme. It still has strategic significance in energy generation, shipping, refining and pharmaceuticals development.[4]

Geography

The main tributary to the harbour is the River Lee which, after flowing through Cork city, passes through the upper harbour (Lough Mahon) in the northwest before passing to the west of Great Island with the main channel emerging into the lower harbour past Haulbowline Island.

For conservation and navigation purposes, the harbour is often separated into "Upper Cork Harbour" (following the River Lee from Cork city to the towns of Passage West and Monkstown) and "Lower Cork Harbour" (separated from the upper harbour by Great Island).[5][6]

The depth of the harbour has been measured at between 4 fathoms (7.3 m) and 14 fathoms (26 m).[7]

Islands

Cork Harbour contains a number of islands of various sizes, some of which are connected to the mainland by bridges. Islands which are or have been inhabited include:

- Great Island – The largest island in Cork Harbour, which includes the town of Cobh

- Fota Island – Containing Fota Wildlife Park, Fota House and the Fota Island Resort Hotel and golf course

- Little Island – A residential and industrial area

- Haulbowline Island – Headquarters of the Irish Naval Service, and former home of the Cork Water Club (1720).[8]

- Spike Island – Former prison island

- Harper's Island – Site of the Harper's Island Wetland Centre[9]

- Hop Island – Site of an equestrian centre

- Weir Island

- Brick Island

- Corkbeg Island – Site of Whitegate oil refinery

- Brown Island

- Rocky Island – Once housed a magazine building for the Royal Navy. Used by Irish Steel for storage until 2002, and now home to 'The Island Crematorium'.

Settlements

Cork city is located slightly upstream on the River Lee on the northwest corner of Cork Harbour. Several of the city's suburbs, including Blackrock, Mahon, Douglas, Passage West and Rochestown lie on Lough Mahon or the Douglas Estuary, both of which are parts of Upper Cork Harbour.

The Lower Harbour has a number of towns around its shores. Passage West, Monkstown, Ringaskiddy and the smaller village of Raffeen are found on the western shore. On the southwestern shore is Crosshaven. Great Island, which forms the northern shore of the lower harbour, houses the town of Cobh. As of 2011, Cobh had a population of about 12,500.[10] The eastern shore is less densely populated, but has two villages Whitegate and Aghada, both home to power plants.

The village of Ballinacurra is on the northeastern spur of the harbour, known as the Ballynacorra River. Due to the recent expansion of the town of Midleton, Ballinacurra has effectively become a suburb of Midleton, so it could also be said that Midleton lies on Cork Harbour.

Military

Cork Harbour hosts the headquarters of the Irish Naval Service. Prior to the transfer of the treaty ports in 1938, Cork Harbour was an important base for the British Royal Navy.

Some of the first coastal defence fortifications built in Cork Harbour date to the 17th century, and were primarily intended to protect the approaches to Cork city. In the 18th century, fortifications were built on and opposite Haulbowline Island to protect the anchorage in Cobh - including Cove Fort (1743). Fort Camden and Fort Carlisle were built at opposite sides of the harbour entrance during the period of the American War of Independence.

The harbour's military significance increased during the Napoleonic Wars, when the naval establishment in Kinsale was transferred to Cork Harbour. The harbour became an important anchorage, which could be used to guard the entrance to the English Channel and maintain the blockade of France. At this time, the naval dockyard on Haulbowline Island was constructed, as well as a fort on Spike Island (later to become Fort Westmoreland) and a number of Martello Towers and other fortifications were added or improved around the harbour.

The fortifications were developed throughout the 19th century[11] and a further fort, Fort Templebreedy, was added to the south of Fort Camden at the beginning of the 20th century. At the time of Irish independence, Cork Harbour was included, along with Berehaven and Lough Swilly, in a list of British naval establishments that would remain under the control of the Royal Navy, although the naval dockyard on Haulbowline Island was handed over to the Irish Free State in 1923.

Although the Royal Navy appreciated the location of Cork Harbour, particularly for submarines, which had a significantly shorter range in the 1920s, maintenance of the fortifications became an issue after Ireland became independent.

The political uncertainty over the future of the treaty ports meant that the British government was not inclined to invest in their upgrade. Also, at the time of their construction, nobody had considered the possibility of air attack and as they were unable to expand, there was no possibility of adding adequate air cover. Finally, if the Irish Free State was hostile during any conflict, the treaty ports would have to be supplied by sea rather than land, wasting resources. In March 1938, the British government announced that the treaty ports would be handed over unconditionally, and on 11 July 1938, the defences at Cork Harbour were handed over to the Irish military authorities at a ceremony attended by Taoiseach Éamon de Valera.

Since being handed over to the Irish military, most of the military installations have ceased to be used for military purposes. Fort Carlisle was renamed Fort Davis and is used by the Defence Forces for training - but is in a somewhat neglected state. Fort Camden became officially known as Fort Meagher and while no longer in military use, has been subject to renovation by local volunteers and enthusiasts, and can be visited by the public on certain days. The fort was officially renamed as of 11 July 2013 as Camden Fort Meagher, to account for both its British military and Irish military history. Locally, the two forts are sometimes known as "Camden" and "Carlisle", rather than their official titles. Fort Westmoreland became Fort Mitchell Spike Island prison, and has since ceased use for military or prison purposes. "Spike" was gifted to Cork County Council by the State and has been renovated as a tourist attraction by council workers and volunteers under the supervision of archaeologists. The fortifications on Haulbowline Island however have been maintained, and are now the headquarters of the Irish Naval Service.

Industry

Cork Harbour is one of the most important industrial areas in Ireland. While several traditional industries such as shipbuilding at Verolme Dockyards, steel-making on Haulbowline Island and fertiliser manufacturing at IFI (Irish Fertiliser Industries) have ceased in recent years, they have been replaced with newer industries and Cork Harbour is now significant within the pharmaceutical industry. Large international firms such as Pfizer, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline and Janssen Pharmaceutica (a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson) are significant employers in the region. There has however been some concern since the post-2008 Irish economic downturn, as several of the pharmaceutical companies in Cork have shed jobs, notably Pfizer which announced the loss of 177 jobs in June 2012.[12] There are in excess of 100 other pharmaceutical firms operating in the Cork Harbour area. The main centres of the pharmaceutical industry are Little Island and Ringaskiddy. Ireland's only oil refinery, Whitegate refinery, is located on the southeastern shore together with the adjacent Whitegate power station.

Marine activity

Commercial

Historically, the navigation and port facilities of the harbour were managed by the Cork Harbour Commissioners. Founded in 1814, the Cork Harbour Commissioners were reorganised as the Port of Cork Company in 1997.[13]

Vessels up to 90,000 tonnes deadweight (DWT) are capable of coming through the harbour entrance. As the shipping channels get shallower the farther inland one travels, access becomes constricted, and only vessels up to 60,000 DWT can sail above Cobh.

The Port of Cork provides pilotage and towage facilities for vessels entering Cork Harbour. All vessels accessing the quays in Cork city must be piloted and all vessels exceeding 130 metres in length must be piloted once they pass within 2.5 nautical miles (4.6 km) of the harbour entrance at a point marked by the Spit Bank Lighthouse which is the landmark boundary for compulsory pilotage.[14][15][16]

The Port of Cork has berthing facilities at Cork city, Tivoli, Cobh and Ringaskiddy. The facilities in Cork city are primarily used for grain and oil transport. Tivoli (downstream of the older city quays) provides container handling, facilities for oil, livestock and ore and a roll on-roll off (Ro-Ro) ramp. Prior to the opening of Ringaskiddy Ferry Port, car ferries sailed from here; now, the Ro-Ro ramp is used by companies importing cars into Ireland. In addition to the ferry terminal, which provides a service to Roscoff in France, Ringaskiddy has a deep water port.

The Port of Cork company is a commercial semi-state company responsible for the commercial running of the harbour as well as responsibility for navigation and berthage in the port. In 2011 the port had a turnover of €21.4 million and made pre-tax profits of €1.2 million.[17] This was down from a turnover of €26.4 million and profits of €5.4 million in 2006. Container traffic increased by 6% in 2011 when 156,667teus were handled at the Tivoli container facility, however this was down from a peak of 185,000 TEUs in 2006.[18] The 2006 figure saw the port at full capacity and the Port drew up plans for a new container facility capable of handling up to 400,000 teus per annum at Ringaskiddy. This was the subject of objections and after an oral planning hearing was held in 2008, the Irish planning board Bord Pleanala rejected the plan due to inadequate rail and road links at the location.[19]

Permission was later granted and work started (2018) on the new port.[citation needed]

There has been an increase in cruise ship visits to Cork Harbour in the early 21st century, with 53 such ships visiting the port in 2011.[17] The majority of these cruise ships berth at Cobh's Deepwater Quay. Historically, Cobh (under its former name Queenstown) was one of the principal ports through which flowed the stream of emigrants stemming from the Great Famine in the 1840s.

There are also a number of private berths around the harbour, with several centred on Whitegate, Passage West, Rushbrooke, Ringaskiddy and Haulbowline.

Recreational

The Royal Cork Yacht Club, claimed as the world's oldest, was founded as 'The Water Club' on Haulbowline Island in the 1720s. When the British Navy took over Haulbowline in 1801, the club moved to Cobh, where their original clubhouse (built in the 1850s) still stands. In the 1960s, the club moved to Crosshaven. There are also boatyards at Crosshaven and two other marinas. There is another marina on Great Island opposite East Ferry, while Monkstown and Blackrock are used for boating, canoeing, windsurfing and jet-skiing. A number of rowing clubs have facilities on the part of the River Lee between Cork city and Blackrock.

See also

- The Emergency

- Plan W

- Joseph Wheeler for further information on 19th century shipbuilding in Cork.

References

Footnotes

- ^ "Cork Harbour". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ Placenames Database of Ireland

- ^ "Surveys - Cork Harbour and Coast". INtegrated Mapping FOr the Sustainable Development of Ireland's MArine Resource (INFOMAR). Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ "Cork harbour is a bustling axis where hope and history ebb and swell". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ^ Horgan, J. J. (1956). "The Port of Cork" (PDF). Journal of the Statistical and Social Inquiry Society of Ireland. XVIX: 43.

- ^ Cork Harbour Special Protection Area - Conservation Objectives - Version 1 (PDF). npws.ie (Report). National Parks and Wildlife Service. November 2014. p. 75. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ^ White (1835), p. 192.

- ^ History of yachting in the South of Ireland 1720-1908

- ^ "The Islands of Ireland: Sanctuary at Harper's Island". irishexaminer.com. Irish Examiner. 11 February 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ "Area Profile for Town - Cobh Legal Town and its Environs" (PDF). Census 2011. Central Statistics Office. 2011.

- ^ Stevenson, I., Fort (Fortress Study Group), 1999 (27), pp113-143

- ^ Rogersand, Stephen. (6 June 2012) Pfizer staff summoned for job loss discussions. Irish Examiner. Retrieved on 23 July 2013.

- ^ "Port History". Port of Cork Company. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ R. Ingram-Brown (1998). Brown's Nautical Almanac: Daily Tide Tables. Brown, Son & Ferguson. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ "Passage West and Monkstown, Cork Harbour". Passagewestmonkstown.ie. Archived from the original on 22 May 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ "Port Of Cork – Notice to Mariners". PortofCork.ie (Google Cache Archive). Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ a b "Port of Cork - 2011 Annual Results (Press Release)". Port of Cork. 13 August 2012.

- ^ "Reports and financial statements for year ended 31 December 2006" (PDF). Port of Cork Company. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 November 2007.

- ^ RTÉ News: Port of Cork €225m development rejected

Sources

- White, Martin (1835). Sailing directions for the English Channel: including a general description of the South Coasts of England and Ireland and a Detailed Account of the Channel Islands (2 ed.). London: Hydrographic Office, Admiralty. OCLC 656744962.