MyPlate

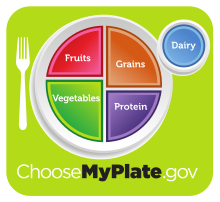

MyPlate is the current nutrition guide published by the United States Department of Agriculture's Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion, and serves as a recommendation based on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.[1] It replaced the USDA's MyPyramid guide on June 2, 2011, ending 19 years of USDA food pyramid diagrams. MyPlate is displayed on food packaging and used in nutrition education in the United States. The graphic depicts a place setting with a plate and glass divided into five food groups that are recommended parts of a healthy diet. This dietary recommendation combines an organized amount of fruits, vegetables, grains, protein, and dairy.[2] It is designed as a guideline for Americans to base their plate around in order to make educated food choices. ChooseMyPlate.gov shows individuals the variety of these 5 subgroups based on their activity levels and personal characteristics.[3]

Background

MyPlate is the latest nutrition guide from the USDA. The USDA's first dietary guidelines were published in 1894 by Dr. Wilbur Olin Atwater as a farmers' bulletin.[4] Since then, the USDA has provided a variety of nutrition guides for the public, including the Basic 7 (1943–1956), the Basic Four (1956–1992), the Food Guide Pyramid (1992–2005), and MyPyramid (2005–2013). MyPlate was established by the USDA in 2011 to combine the recommendations of these past nutrition guides into a graphic that was easy to read.[5]

Many other governments and organizations have created nutrition guides. Some, like the United Kingdom's Eatwell Plate,[6] the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating,[7] and the American Diabetes Association's Create Your Plate system,[8] also use plate diagrams.

In December 2018, the USDA released plans to modify the MyPlate limits on milk, sodium, school breakfast, and school lunch options.[9][10] Current nutritional research continues to make new daily intake recommendations which the USDA has been adding to newer modifications of MyPlate.[11]

Guidelines

MyPlate is divided into four sections of approximately 30 percent grains, 40 percent vegetables, 10 percent fruits and 20 percent protein, accompanied by a smaller circle representing dairy, such as a glass of milk or a yogurt cup.

MyPlate is supplemented with an additional recommendations, such as "Make half your plate fruits and vegetables", "Switch to 1% or skim milk", "Make at least half your grains whole", and "Vary your protein food choices."[12] The guidelines also recommend portion control while still enjoying food, as well as reductions in sodium and sugar intakes.[11]

"Make half your plate fruits and vegetables" is one of the main recommendations presented through MyPlate's design. Many Americans fail to consume the proper number of fruits and vegetables or do not incorporate a variety of this particular food group.[citation needed] The 2010 Dietary Guidelines recommends increasing fruits and vegetable consumption due to the associated health benefits.[13] Fruits and vegetables are rich in vitamins and minerals such as vitamin C, dietary fibers, and folate.[14] These nutrients are further linked with health benefits such as protecting against a variety of diseases, promoting healthy aging, and lowering the risk of certain cancers.[15] These prominent health benefits associated with fruits and vegetables explain the emphasis by MyPlate for making this food group take it half of one's plate.

MyPlate focuses primarily on the addition of fruits and vegetables, into a diet due to the nutritional benefits associated with these food groups. This nutritional recommendation suggests including a variety of both of these food groups in order to gain maximum levels of nutrients. MyPlate suggests choosing from a mix of different colors of fruits and vegetables in order to maximize the intake of vitamins and minerals.[2]

In unveiling MyPlate, First Lady Michelle Obama said, "Parents don't have the time to measure out exactly three ounces of chicken or to look up how much rice or broccoli is in a serving. ... But we do have time to take a look at our kids' plates. ... And as long as they're eating proper portions, as long as half of their meal is fruits and vegetables alongside their lean proteins, whole grains and low-fat dairy, then we're good. It's as simple as that."[16]

Michelle Obama's and her Let’sMove! Initiative have targeted the MyPlate icon as a positive nutritional guideline to help reduce national obesity trends. The Let’sMove Initiative has the main goal of creating a healthy life for children in order to produce a healthier population in the future. Michelle Obama's initiative has chosen to promote MyPlate and ChooseMyPlate.gov in order to help pursue the overall goal of lessening nation-wide obesity.[17]

National strategic partners

The USDA has created partnerships with a number of organizations to help promote the messages of MyPlate and spread the reach as far and wide as possible. These partners consist of companies and organizations national in scope and reach that have agreed to "promote nutrition content in the context of the entirety of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans".[18] These companies most follow the mission stated by the Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion and participate in sessions that are focused on nutritional planning techniques. The USDA has the support of numerous national partners with emphasis on grocery retailers, healthcare companies, and food chains.[18]

Criticism and controversy

MyPlate was widely received as an improvement on the previous MyPyramid icon, which had been criticized as too abstract and confusing.[19][20][21] The 50-percent emphasis on fruits and vegetables, as well as the simplicity and understandability of the plate image, were particularly praised. The Food Pyramid was not a strong guideline considering many individuals struggled incorporating it into their daily life. Many details such as the recommended daily intake were left out of this nutritional guideline which confused the general population.[22] MyPlate was the revised version with a visual that made the recommendations very clear and easy to understand.

Although MyPlate implements might contain dietary guidelines that are nutritional beneficial, it has occasional disadvantages. The guidelines fail to explain plate size, include snack recommendations, or give examples of healthy foods for each category.[22]

Some critics said the protein section is unnecessary, given that protein is available from other food groups, and Americans on average already eat enough; however, meat would not fit in any of the other food groups. The dairy section was criticized by some as similarly dispensable. An additional critique was that the icon is too simple, missing opportunities for additional dietary advice, such as distinctions between healthy and unhealthy proteins or guidance on good fats and bad fats.[19][23]

Reason magazine stated in an article from December 2022 that, "The federal government continues to be very bad at telling people what and how to eat." and further criticized the MyPlate program as also being poorly marketed in that fewer than 3 out of 4 polled Americans were aware of the program.[24]

The Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH) released their own adjusted and more detailed version of MyPlate, called the Harvard Healthy Eating Pyramid, in response.[25] The Healthy Eating Pyramid was suggested as an alternative to MyPlate that is more up-to-date with scientific nutritional findings. Harvard's plate features a higher ratio of vegetables to fruits, adds healthy oils to the recommendation, and balances healthy (type of) protein and whole grains as equal quarters of the plate, along with recommending water and suggesting sparing dairy consumption.[26] HSPH Chair of the Department of Nutrition, Walter Willett, criticized MyPlate, saying: "unfortunately, like the earlier U.S. Department of Agriculture pyramids, MyPlate mixes science with the influence of powerful agricultural interests, which is not the recipe for healthy eating".[27] The Harvard plate also contains a recommendation for physical activity which MyPlate tends to leave out. This more refined nutritional guideline states a more exact protocol to follow in regards to the consumption of fats and grains with an individual's specific weight and workout routine in mind.

Harvard Medical School also pushes for the inclusion of water in their nutritional guidelines.[26] MyPlate recommends the consumption of milk or some form of dairy without explicitly encouraging drinking water. The Healthy Eating Pyramid has included a section to their plate that focuses on adding water or non-sugar beverages to one's daily intake.[26]

According to Dr. Marion Nestle, former chair of the Department of Nutrition, Food Studies, and Public Health at New York University, "There’s a great deal of money at stake in what these guidelines say."[28] Talking about her work as an U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and USDA expert, she said "I was told we could never say ‘eat less meat’ because USDA would not allow it."[28]

MyPlate Expansion

Starting in 2021, the Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion has broadened its reach to target more of the general population rather than keeping its focus audience in America. The MyPlate icon has been translated into eighteen different languages in order to encourage the eating habits of individuals around the world.[29] There are now icons and informational sheets in a variety of Asian languages as well as Spanish.[30] MiPlato is a version of the MyPlate guidelines that is translated in order to be understood by a broader range of the population.[5] This along with the broadening of MyPlate's social media accounts has expanded the MyPlate influence across many platforms. CNPP has been working to broaden these resources for health professionals and interested individuals.[29]

See also

- 5 A Day

- Food and Nutrition Service

- Food guide pyramid

- Healthy diet

- Healthy eating pyramid

- Human nutrition

References

- ^ "Dietary Guidelines for Americans". 2015-12-14. doi:10.1377/hpb20151214.174872.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b "Back to Basics: All About MyPlate Food Groups". www.usda.gov. Retrieved 2022-01-21.

- ^ "Tools | MyPlate". www.myplate.gov. Retrieved 2022-01-21.

- ^ "Dietary Recommendations and How They Have Changed Over Time". America's Eating Habits: Changes and Consequences. United States Department of Agriculture. May 1999. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ a b "Evolution of USDA Food Guides to Today's MyPlate". Riley Children's Health. Retrieved 2022-02-10.

- ^ "The eatwell plate". National Health Service. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ "The Australian Guide to Healthy Eating - Enjoy a Variety of Foods Every Day". Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ "Create Your Plate". American Diabetes Association. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ "USDA Publishes School Meals Final Rule | Food and Nutrition Service". www.fns.usda.gov. Archived from the original on 2018-12-07.

- ^ Hohman, Maura (December 7, 2018). "USDA Rolls Back Michelle Obama's School Lunch Regulations, Allowing More Salt and Fat". people.com.

- ^ a b "USDA's MyPlate". United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ "Let's eat for the health of it" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 June 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ "2010 Dietary Guidelines Released". Food and Health Communications. 2011-01-31. Retrieved 2022-01-21.

- ^ "Fruits & Veggies – More Matters! | HealthySD.gov". healthysd.gov. 21 September 2015. Retrieved 2022-01-21.

- ^ Jayawardena, Ranil; Sooriyaarachchi, Piumika; Punchihewa, Pavani; Lokunarangoda, Niroshan; Kirthi Pathirana, Anidu (2019). "Effects of "plate model" as a part of dietary intervention for rehabilitation following myocardial infarction: a randomized controlled trial". Cardiovascular Diagnosis and Therapy. 9 (2): 179–188. doi:10.21037/cdt.2019.03.04. PMC 6511685. PMID 31143640.

- ^ Sweet, Lynn (2 June 2011). "Michelle Obama hypes icon switch: Bye food pyramid, hello food plate. Transcript". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ^ "First Lady, Agriculture Secretary Launch MyPlate Icon as a New Reminder to Help Consumers to Make Healthier Food Choices | Food and Nutrition Service". www.fns.usda.gov. Retrieved 2022-01-20.

- ^ a b "USDA MyPlate National Strategic Partners". ChooseMyPlate.gov. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ a b Carman, Tim (2 June 2011). "Michelle Obama and USDA unveil nutritional plate icon". The Washington Post. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ Hellmich, Nanci (3 June 2011). "USDA serves nutrition guidelines on 'My Plate". USA Today. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ "Pyramid tossed, dinner plate is new U.S. meals plan". Reuters. 2 June 2011. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ a b "A Detailed Guide to Using MyPlate Plus Food Lists, and a 7-Day Meal Plan". EverydayHealth.com. Retrieved 2022-02-03.

- ^ Kotz, Deborah (2 June 2011). "New food plate icon: will it change how you eat?". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ Linnekin, Baylen (10 December 2022). "'MyPlate,' the USDA's 'Food Pyramid' Replacement, Is Also a Dud". reason.com. Reason. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ "Healthy Eating Plate". The Nutrition Source. 2012-09-18. Retrieved 2022-02-10.

- ^ a b c "Comparison of the Healthy Eating Plate and the USDA's MyPlate". Harvard Health. 2011-09-13. Retrieved 2022-02-10.

- ^ Datz, Todd (14 September 2011). "Harvard serves up its own 'Plate'". Harvard Gazette. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ^ a b Heid, Markham (8 January 2016). "Experts Say Lobbying Skewed the U.S. Dietary Guidelines". Time. Retrieved 2017-06-26.

- ^ a b "MyPlate Broadens its Reach". www.usda.gov. Retrieved 2022-02-10.

- ^ "MyPlate Graphics | MyPlate". www.myplate.gov. Retrieved 2022-02-10.