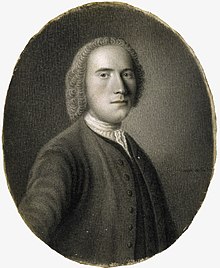

George Murray (general)

Lord George Murray | |

|---|---|

Lord George Murray | |

| Born | 4 October 1694 Huntingtower, Perth, Scotland |

| Died | 11 October 1760 (aged 66) Medemblik, the Netherlands |

| Buried | Bonifaciuskerk, Medemblik[1] |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1711–1715 (British Army) 1715–1719 (Jacobite) 1745–1746 (Jacobite) |

| Rank | Lieutenant (British Army) Lieutenant General (Jacobite) |

| Battles / wars | |

| Relations | John Murray, 1st Duke of Atholl (father) John Murray, 3rd Duke of Atholl (son) |

Lord George Murray (4 October 1694 – 11 October 1760), sixth son of John Murray, 1st Duke of Atholl, was a Scottish nobleman and soldier who took part in the Jacobite rebellions of 1715 and 1719 and played a senior role in that of 1745.

Pardoned in 1725, he returned to Scotland, where he married and in 1739 took the oath of allegiance to George II. When the 1745 Rising began, Murray was appointed sheriff depute to Sir John Cope, government commander in Scotland but then joined the Jacobite army when it arrived in Perth on 3 September. As one of the senior commanders, he made a substantial contribution to their early success, particularly reaching and successfully returning from Derby.

However, his support for the 1707 Union set him apart from the majority of Scottish Jacobites, and previous links with the government meant that many viewed him with suspicion: combined with a perceived arrogance and inability to accept advice, this reduced his military effectiveness.

After the Battle of Culloden in April 1746, Murray went into exile in Europe and was excluded from the 1747 Act of Indemnity. He died in the Dutch town of Medemblik in 1760, and his eldest son, John, later became the 3rd Duke of Atholl.

Biography

Lord George Murray was born on 4 October 1694, at Huntingtower Castle near Perth, sixth son of John Murray, Duke of Atholl (1660–1724) and his first wife, Katherine Hamilton (1662–1707). As a younger son, 'Lord' was a courtesy title.[2]

In June 1728, he married Amelia (1710–1766), daughter of James Murray of Strowan and Glencarse. They had three sons and two daughters who survived to adulthood; John, later 3rd Duke of Atholl (1729–1774), Amelia (1732–1777), James (1734–19 March 1794), later a Major-General in the British army, Charlotte (?–1773) and George (1741–1797), who became an admiral in the Royal Navy.[2]

Career

Murray entered Glasgow University in 1711 but left to join the British army in Flanders, and was commissioned as a lieutenant in March 1712. The War of the Spanish Succession was in its closing stages, and it is unlikely he saw any action before it ended with the Peace of Utrecht in 1713.[3]

Queen Anne died in August 1714 and was succeeded by the Hanoverian George I, with the Whigs taking power. Deprived of office, several senior Tories defected to the Jacobite cause, including the Earl of Mar. In September 1715, he launched a rebellion in Scotland.[4]

Like many other members of the nobility, Atholl sought to avoid direct participation himself, while balancing the two causes. His eldest son James fought for the government, although Murray joined the Jacobite army, along with his brothers Tullibardine (1689–1746) and Lord Charles (1691–1720). Atholl wrote letters to all three, forbidding them to participate in the Rebellion, which he later produced as evidence of his loyalty.[5]

Lord Charles was captured at Preston; Tullibardine fought at Sheriffmuir, but Lord George missed the battle, as he was collecting taxes in Fife.[2] While Sheriffmuir was inconclusive, without external support the Rebellion collapsed; Lord Charles, who held a commission in the 5th Dragoons, was tried as a deserter and sentenced to be shot. Although he was pardoned, his brothers were excluded and fled to France.[6]

In 1717, the Murrays were involved in efforts to gain support for an invasion from Sweden, then in dispute with Hanover over Pomerania. This was resurrected as part of the 1719 Rebellion, whose main component was a Spanish landing in South-West England; its objective was to capture Inverness, and enable a Swedish naval expeditionary force to disembark. Charles XII of Sweden died in November 1718, ending any hope of Swedish support, and the entire purpose of the Scottish uprising.[7]

Tullibardine and Lord George arrived in Stornoway in April 1719, where they met up with other exiles, including 300 Spanish marines under George Keith. The rebellion collapsed after defeat in the Battle of Glenshiel on 10 June; Lord George was wounded, and later escaped to Rotterdam.[8] This seemed to end hopes of a Stuart restoration; in a letter of 16 June 1719 to the Earl of Mar, Tullibardine concluded 'it bid fair to ruin the King's Interest and faithful subjects in these parts.'[9] Senior leaders like Bolingbroke and the Earl of Seaforth were allowed home, while James and George Keith became Prussian officers. This partially explains the post-1746 bitterness towards those like Murray and Lochiel, pardoned for their roles in 1715 and 1719.[10]

Murray's activities over the next four years are obscure, but included attending the Académie royale des sciences de Paris and fighting a duel with fellow Jacobite exile Campbell of Glendaruel. It has also been suggested he unsuccessfully applied for commissions in the Venetian and Savoyard armies. He returned to Scotland in 1724 to visit his dying father; he was pardoned the next year, married and leased a small country estate from his brother James. He seemed to have ended support for the Stuart cause and rejected suggestions his eldest son be educated in France, sending him to Eton instead.[11] In 1739, he swore the Oath of Allegiance to George II although he later claimed this was purely to help his half-brothers be elected as MPs for Perthshire.[12]

The 1745 Rising

After Charles landed on Eriskay in July 1745, accompanied by the now elderly and sick Tullibardine, Murray was appointed sheriff depute for Perthshire and advisor to the government commander Sir John Cope. To the surprise of both sides, he joined the Jacobites when they reached Perth on 3 September, writing a letter of self-justification to his elder brother the Duke of Atholl.[13]

His reasons remain obscure; at the time, he cited the government's "corruption and bribery" and "wars all entered into for and on account of the Electors of Hanover" as necessitating "a Revolution to secure our liberties".[14] In a letter written after the Rising, Murray said it was his "greatest honour [...] to suffer in so just and upright a cause" and complained "most people in Britain now regard neither probity nor any other virtue — all is selfish".[15]

Accepting a pardon in 1725, swearing allegiance to George II in 1739 and taking a position under the same 'corrupt government' meant others viewed his actions as the opposite of virtuous and honest, including his eldest son.[16] Many Jacobites were also suspicious and while his knowledge of Highland military customs was an asset, Murray's appointment heightened tensions with the Franco-Irish exiles. The most important was John O'Sullivan, a former French officer acting as chief of staff.[17]

There were various reasons for the poor relationships between the senior commanders, one being a generalised Scottish resentment of the exiles, who were perceived as risking relatively little. The Scots faced execution as rebels and loss of titles and lands; as many of the exiles held French commissions, they would be treated as prisoners of war and exchanged. Another was Murray's poorly concealed view Charles was a 'reckless adventurer.'[18]

Murray considered O'Sullivan's expectations of the Highland recruits unrealistic, including formal drill and enacting written orders, while the exiles viewed this as outdated. There was some truth in both positions; many Scots served in European armies, while a second battalion of the Royal Ecossaise was raised in Perth and performed well. However, these came from the relatively urbanised Lowlands; the military aspects of clan society had been in decline for over a century and most Highland recruits were illiterate farmworkers.[19]

One of the exiles, Sir John MacDonald, wrote Murray's strategic vision was jeopardised by ignorance of tactical execution, an example being the failed night march before Culloden.[20] James Johnstone, usually an admirer, recorded his talents were offset by a quick temper, arrogance and inability to take advice.[21] One example was a furious argument with Charles prior to the Battle of Prestonpans; although his rejection of a frontal assault in favour of attacking Cope's left flank proved correct, it caused deep offence.[22]

In general, Murray's views were often well-founded, if not always correct, but poorly presented. His opinion of Charles was widely shared; MacDonald of Sleat refused to join the rebellion as a result, while French envoy d’Éguilles later suggested a Scots Republic was preferable to a Stuart restoration.[23] However, most of those who opposed invading England did so because dissolving the Union seemed achievable; since Murray wanted to retain it, his objectives remain unclear. Finally, his proposal that Catholics be removed from positions of command made sense in terms of propaganda, but unwise, since Charles and most of his advisors were Catholic.[2]

Despite their doubts, the Scots agreed to the invasion, largely because Charles told them that he had received personal assurances of both English and French support. O'Sullivan felt their army was too small to conquer England but lack of recruits and money made action imperative; Edinburgh had been 'devastated for 30 miles around' by Jacobite foragers and the prisoners taken at Prestonpans were released because they could not feed them. Shortly after entering England, Charles received reports of pro-Hanoverian 'disorders' in Edinburgh and Perth, connected to celebrations for George II's birthday on 9 November.[24]

Murray selected a route through North-West England, an area strongly Jacobite in 1715; the first stop was Carlisle, which surrendered on 14 November. He then resigned his command, ostensibly because Charles refused to rotate troops besieging the castle, but in reality because he was unhappy about serving under his fellow lieutenant-general, the well-liked but inexperienced Catholic Duke of Perth.[25]

Perth gracefully resigned and Murray reinstated but it further damaged his relationship with Charles, which was then comprehensively destroyed by the decision to retreat made at Derby on 5 December. Charles blamed him for the rest of his life but many Scots wanted to turn back at Carlisle, Preston and Manchester, continuing only when Murray persuaded them otherwise. In an era when a gentleman's word was his bond, it is also hard to overstate the damage caused when Charles admitted he lied about assurances of support given at Edinburgh and Manchester.[26]

The retreat was conducted with the same efficiency as the advance; Murray led a successful rearguard action against government dragoons on 18 December at Clifton Moor. While the invasion achieved little, reaching Derby and returning was a considerable military achievement. Strengthened by new recruits and around 200 Irish and Scottish French regulars, the Jacobites besieged Stirling Castle. They dispersed a relief force at the Battle of Falkirk Muir on 17 January, but abandoned the siege shortly afterwards and withdrew to Inverness.[27]

Traditional Highland warfare stopped in the winter months; as with Prestonpans, the trickle of clansmen returning home with their booty turned into a flood after Falkirk. Murray's own Atholl Brigade was particularly affected: "For God's sake make examples", Murray urged Tullibardine on 27 January, "or we shall be undone".[28] The decision to retreat was approved by the vast majority, but Murray later noted "I was mostly blamed for it".[29]

He led the Atholl raids of 14 to 17 March, intended to support his argument guerrilla warfare was a better strategic choice. While these were partially successful, he was unable to capture the family home of Blair Castle and by spring, the Jacobites were short of money, food and weapons.[30] When Cumberland advanced north from Aberdeen on 8 April, the leadership agreed battle was the best option; the choice of location has been debated ever since but defeat was a combination of factors.[31] Exhausted by a failed night march suggested by Murray in an attempt to surprise Cumberland's army, many of their troops missed the Battle of Culloden on 16 April, which ended in a decisive government victory.[32]

Over the next two days, an estimated 1,500 survivors assembled at Ruthven Barracks but on 20 April, Charles ordered them to disperse until he returned with additional support. He left for France in September and never returned to Scotland, although the collapse of his relationship with the Scots always made this unlikely. Tullibardine was captured, and died in the Tower of London in July, while Murray escaped to the Dutch Republic in December 1746.[33]

Aftermath and legacy

In March 1747, Murray journeyed to Rome for an audience with James, who granted him a pension. Charles asked his father to imprison him and the two never met again, though Murray continued to write both to Charles and to his secretary reiterating his loyalty. His wife Amelia joined him in exile and they eventually settled in Medemblik where Murray died on 11 October 1760. Despite his father's attainder, his son was allowed to succeed his brother James as Duke of Atholl in 1764.[2]

Unlike many of his colleagues, Murray claimed his motivation was not Scottish nationalism but 'that the prestige of Great Britain should be upheld among the nations of the world.'[34] This suggests the Hanoverians' greatest failing in his eyes was being foreign, an attribute shared by Charles, a young man brought up in Italy whose first language was French, and whose mother was Polish.[35]

Much of the past historiography of the Rising focused on responsibility for defeat, with Murray's role arguably over-emphasised at the expense of his colleagues, O'Sullivan in particular. Historian Murray Pittock summarises his character and abilities as follows; If we do not take temperament for achievement, it may be more fairly said that Lord George Murray was a brave, petulant, and gifted - though conservative — field commander.[2]

References

- ^ "Bonifacius Church (Bonifaciuskerk), Medemblik". Holland Tour. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Pittock 2006.

- ^ Dalton 1904, p. 125.

- ^ Von Ehrenstein 2004.

- ^ Atholl 1907, p. 188.

- ^ Szechi 1994, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Black 2005, p. 304.

- ^ Lenman 1980, p. 192.

- ^ Ormonde 1895, p. 136.

- ^ Szechi & Sankey 2001, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Henshaw 2014, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Henshaw 2014, p. 109.

- ^ Atholl 1907, pp. 19–20.

- ^ McLynn 1982, pp. 109–110, 139.

- ^ Blaikie & Garden 1907, p. 41.

- ^ Riding 2016, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Reid 2006, pp. 90–92.

- ^ McLynn 1983, p. 46.

- ^ Mackillop 1995, p. 2.

- ^ Tayler 1948, p. 67.

- ^ Riding 2016, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Tomasson & Buist 1978, p. 52.

- ^ McLynn 1980, pp. 177–181.

- ^ Riding 2016, pp. 200–201.

- ^ Maxwell 1747, p. 65.

- ^ Riding 2016, pp. 300–301.

- ^ Riding 2016, pp. 377–378.

- ^ Atholl 1907, pp. 160–161.

- ^ Chambers 1834, p. 99.

- ^ Riding 2016, p. 386.

- ^ Pittock 2016, pp. 58–64.

- ^ Riding 2016, p. 427.

- ^ Riding 2016, p. 429.

- ^ Henshaw 2014, p. 111.

- ^ Tomasson & Buist 1978, p. 11.

Sources

- Atholl, John, Duke of, ed. (1907). The Chronicles of the Atholl and Tullibardine Families; Volumes II & III. Ballentyne Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Black, Jeremy (2005). "Hanover and British Foreign Policy 1714-60". The English Historical Review. 120 (486): 303–339. doi:10.1093/ehr/cei117. JSTOR 3490922.

- Blaikie, Murdoch; Garden, William (1907). The Spirit of Jacobite Loyalty: An Essay Toward a Better Understanding of "The Forty Five". Brown.

- Chambers, Robert (1834). History of the Rebellion of 1745–6 (2017 ed.). Forgotten Books. ISBN 978-1-333-57442-0.

- Dalton, Charles (1904). English army lists and commission registers, 1661-1714 Volume VI. Eyre and Spottiswood.

- Hamilton, Douglas (2014). Jacobitism, Enlightenment and Empire, 1680–1820. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-84893-466-5.

- Henshaw, Victoria (2014). Scotland and the British Army, 1700-1750: Defending the Union. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-4742-6926-1.

- Kennedy, Allan (2016). "Rebellion, Government and the Scottish Response to Argyll's Rising of 1685" (PDF). Journal of Scottish Historical Studies. 36 (1): 8. doi:10.3366/jshs.2016.0167.

- Lenman, Bruce (1980). The Jacobite Risings in Britain 1689-1746. Eyre Methuen. ISBN 0-413-39650-9.

- Mackillop, Andrew (1995). Military Recruiting in the Scottish Highlands 1739–1815: the Political, Social and Economic Context (PhD). University of Glasgow. OCLC 59608677.

- Maxwell, James (1747). Narrative of Charles Prince of Wales' Expedition to Scotland in the Year 1745. Maitland Club.

- McLynn, FJ (1983). The Jacobite Army in England, 1745-46: The Final Campaign. John Donald Publishers. ISBN 978-0-85976-093-5.

- McLynn, FJ (1982). "Issues and motives in the Jacobite rising of 1745". The Eighteenth Century. 23 (2).

- McLynn, Frank (1980). "An Eighteenth-Century Scots Republic? An Unlikely Project from Absolutist France". The Scottish Historical Review. 59 (168): 177–181. JSTOR 25529380.

- Ormonde, James Butler (1895). Dickson, William Kirk (ed.). The Jacobite Attempt Of 1719 Letters Of James Butler, Second Duke Of Ormonde (2015 ed.). Sagwan Press. ISBN 978-1-296-88217-4.

- Pittock, Murray GH (2006). "Murray, Lord George". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/19605. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Pittock, Murray (2016). Great Battles; Culloden (First ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-966407-8.

- Reid, Stuart (2006). The Scottish Jacobite Army 1745–46. Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-073-4.

- Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites: A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4088-1912-8.

- Szechi, Daniel (1994). The Jacobites: Britain and Europe, 1688–1788. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-3774-0.

- Szechi, Daniel; Sankey, Margaret (2001). "Elite Culture and the Decline of Scottish Jacobitism 1716-1745". Past and Present. 173 (1): 90–128. doi:10.1093/past/173.1.90. ISSN 0031-2746. JSTOR 3600841.

- Tayler, Henrietta (1948). A Jacobite Miscellany: Eight Original Papers on the Rising of 1745-6. Roxburghe Club.

- Tomasson, Katherine; Buist, Francis (1978). Battles of the Forty-five. HarperCollins Distribution Services. ISBN 978-0-7134-0769-3.

- Von Ehrenstein, Christoph (2004). "Erskine, John, styled twenty-second or sixth earl of Mar and Jacobite duke of Mar". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8868. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1694 births

- 1760 deaths

- Scottish generals

- Scottish Jacobites

- Younger sons of dukes

- King's Own Royal Regiment officers

- British Army personnel of the War of the Spanish Succession

- People of the Jacobite rising of 1715

- People of the Jacobite rising of 1719

- Jacobite military personnel of the Jacobite rising of 1745

- Military personnel from Perth and Kinross

- Clan Murray