Convoy PQ 16

| Convoy PQ 16 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Arctic naval operations of the Second World War | |||||||

German occupied Norway (in green) lay along the flank of the sea route to northern Russia | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Allies | Germany | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Newell Gale (convoy) Richard Onslow (escorts) |

Alexander Holle Hans Roth Hermann Busch | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| PQ 16 and escorts | Luftflotte 5 | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

36 merchant ships varying number of escorts | 108 aircraft | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

7 ships sunk 1 turned back |

3–6 aircraft shot down 1 damaged 2 U-boats damaged | ||||||

Convoy PQ 16 (21–30 May 1942) was an Arctic convoy of British, United States and Allied ships from Iceland to Murmansk and Archangelsk in the Soviet Union during the Second World War. The convoy was the largest yet and was provided with a considerable number of escorts and submarines. QP 12, a return convoy, sailed on the same day

As Operation Barbarossa the German invasion of the Soviet Union had failed in 1941, the Germans began to build up forces in Norway to intercept Arctic convoys with ships, aircraft and U-boats rather than rely on a quick victory. Luftflotte 5 (Air Fleet 5), the Luftwaffe in force Norway, was reinforced with bombers and torpedo-bombers in early 1942 and reorganised to attack convoys as they passed between the Norwegian coast and the ice of the Arctic, which was still close to its southern winter limit.

The sun remained above the horizon at this time of year and the deck crews of the ships found the perpetual daylight fatiguing and stressful; glare from sunshine reflecting off ice being particularly difficult for observers. On 25 May air attacks began, the German bombers and torpedo-bombers co-ordinating their attacks. Torpedo-bombers launched at the same time to make it harder for ships to evade the torpedoes. The air attacks continued until 1 June and sank six ships, one other being lost to a U-boat; 3–6 German aircraft were shot down and one damaged; on 27 May, 108 attacks by aircraft had been counted.

After the convoy, the escort commander recommended that convoys be given far more anti-aircraft fire-power and air cover from an escort carrier. The Germans claimed the virtual destruction of the convoy and concluded that air operations were more effective than submarine attacks in the long hours of daylight. The German tactic of combined dive-bombing and torpedo-bombing, with the torpedoes being dropped in a salvo (Golden comb) was vindicated.

Background

Lend-lease

After Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the USSR, began on 22 June 1941, the UK and USSR signed an agreement in July that they would "render each other assistance and support of all kinds in the present war against Hitlerite Germany".[1] Before September 1941 the British had dispatched 450 aircraft, 22,000 long tons (22,000 t) of rubber, 3,000,000 pairs of boots and stocks of tin, aluminium, jute, lead and wool. In September British and US representatives travelled to Moscow to study Soviet requirements and their ability to meet them. The representatives of the three countries drew up a protocol in October 1941 to last until June 1942 and to agree new protocols to operate from 1 July to 30 June of each following year until the end of Lend-Lease. The protocol listed supplies, monthly rates of delivery and totals for the period.[2]

The first protocol specified the supplies to be sent but not the ships to move them. The USSR turned out to lack the ships and escorts and the British and Americans, who had made a commitment to "help with the delivery", undertook to deliver the supplies for want of an alternative. The main Soviet need in 1941 was military equipment to replace losses because, at the time of the negotiations, two large aircraft factories were being moved east from Leningrad and two more from Ukraine. It would take at least eight months to resume production, until when, aircraft output would fall from 80 to 30 aircraft per day. Britain and the US undertook to send 400 aircraft a month, at a ratio of three bombers to one fighter (later reversed), 500 tanks a month and 300 Bren gun carriers. The Anglo-Americans also undertook to send 42,000 long tons (43,000 t) of aluminium and 3, 862 machine tools, along with sundry raw materials, food and medical supplies.[2]

Arctic Ocean

Between Greenland and Norway are some of the most stormy waters of the world's oceans, 890 mi (1,440 km) of water under gales full of snow, sleet and hail. Around the North Cape and the Barents Sea the sea temperature rarely rises about 4° Celsius and a man in the water would probably die unless rescued immediately. The cold water and air made spray freeze on the superstructure of ships, which had to be removed quickly to avoid the ship becoming top-heavy. The cold Arctic water was met by the Gulf Stream, warm water from the Gulf of Mexico, which became the North Atlantic Drift, arriving at the south-west of England the drift moves between Scotland and Iceland. North of Norway the drift splits.[3]

A northern stream goes north of Bear Island to Svalbard and the southern stream following the coast of Murmansk into the Barents Sea. The mingling of cold Arctic water and warmer water of higher salinity generates thick banks of fog for convoys to hide in but the waters drastically reduced the effectiveness of ASDIC as U-boats moved in waters of differing temperatures and density. In winter, polar ice can form as far south as 50 mi (80 km) of the North Cape and in summer it can recede to Svalbard, forcing ships closer to Luftwaffe air bases or being able to sail further out to sea. The area is in perpetual darkness in winter and permanent daylight in the summer which makes air reconnaissance almost impossible or easy.[3]

Arctic convoys

In October 1941, the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, made a commitment to send a convoy to the Arctic ports of the USSR every ten days and to deliver 1,200 tanks a month from July 1942 to January 1943, followed by 2,000 tanks and another 3,600 aircraft in excess of those already promised.[1][a] The first convoy was due at Murmansk around 12 October and the next convoy was to depart Iceland on 22 October. A motley of British, Allied and neutral shipping loaded with military stores and raw materials for the Soviet war effort would be assembled at Hvalfjörður in Iceland, convenient for ships from both sides of the Atlantic.[5] By late 1941, the convoy system used in the Atlantic had been established on the Arctic run; a convoy commodore ensured that the ships' masters and signals officers attended a briefing to make arrangements for the management of the convoy, which sailed in a formation of long rows of short columns. The commodore was usually a retired naval officer or a Royal Naval Reserveist and would be aboard one of the merchant ships (identified by a white pendant with a blue cross). The commodore was assisted by a Naval signals party of four men, who used lamps, semaphore flags and telescopes to pass signals in code.[6][b]

In large convoys, the commodore was assisted by vice- and rear-commodores with whom he directed the speed, course and zig-zagging of the merchant ships and liaised with the escort commander.[6][c] During the summer months, convoys went as far north as 75 N latitude then south into the Barents Sea and to the ports of Murmansk in the Kola Inlet and Archangel in the White Sea. In winter, due to the polar ice expanding southwards, the convoy route ran closer to Norway.[8] Until early March 1942 one merchant ship of the 110 sent via the Arctic route had been lost; the condition of the receiving ports in the USSR caused more difficulty than German anti-convoy operations by ships, submarines and aircraft. As the summer season approached the hours of daylight increased just as the size of convoys got bigger to alleviate the accumulation of ships awaiting dispatch.[2]

British grand strategy

The growing German air strength in Norway and increasing losses to convoys and their escorts, particularly to convoys PQ 15 and QP 11, led Rear-Admiral Stuart Bonham Carter, commander of the 18th Cruiser Squadron, Admiral sir John Tovey, Commander in Chief Home Fleet and Admiral Sir Dudley Pound the First Sea Lord, the professional head of the Royal Navy, unanimously to advocate the suspension of Arctic convoys during the summer months. The small number of Russian ships available for Arctic convoys, losses inflicted by Luftflotte 5 based in Norway and the presence of the German battleship Tirpitz in Norway from early 1942, had led to a large number of ships full of supplies to Russia becoming stranded at the west end and empty and damaged ships waiting at the east end.[9] Despite the views of the Navy, Churchill came under pressure from the president of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Soviet leader, Joseph Stalin, bowed to political reality and ordered the dispatch of a larger convoy to reduce the backlog,

The operation is justified if half gets through. Failure on our part to make the attempt would weaken our influence with both our major allies.

— Winston Churchill[10]

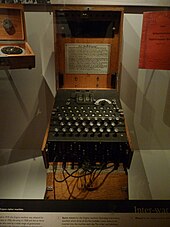

Signals intelligence

Bletchley Park

The British Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) based at Bletchley Park housed a small industry of code-breakers and traffic analysts. By June 1941, the German Enigma machine Home Waters (Heimish) settings used by surface ships and U-boats could quickly be read. On 1 February 1942, the Enigma machines used in U-boats in the Atlantic and Mediterranean were changed but German ships and the U-boats in Arctic waters continued with the older Heimish (Hydra from 1942, Dolphin to the British). By mid-1941, British Y-stations were able to receive and read Luftwaffe W/T transmissions and give advance warning of Luftwaffe operations.[11][12]

In 1941, naval Headache personnel with receivers to eavesdrop on Luftwaffe wireless transmissions were embarked on warships and from May 1942, ships gained RAF Y computor parties, which sailed with cruiser admirals in command of convoy escorts, to interpret Luftwaffe W/T signals intercepted by the Headaches. The Admiralty sent details of Luftwaffe wireless frequencies, call signs and the daily local codes to the computors, which combined with their knowledge of Luftwaffe procedures, could glean fairly accurate details of German reconnaissance sorties. Sometimes computors predicted attacks twenty minutes before they were detected by radar.[11][12]

B-Dienst

The rival German Beobachtungsdienst (B-Dienst, Observation Service) of the Kriegsmarine Marinenachrichtendienst (MND, Naval Intelligence Service) had broken several Admiralty codes and cyphers by 1939, which were used to help Kriegsmarine ships elude British forces and provide opportunities for surprise attacks. From June to August 1940, six British submarines were sunk in the Skaggerak using information gleaned from British wireless signals. In 1941, B-Dienst read signals from the Commander in Chief Western Approaches informing convoys of areas patrolled by U-boats, enabling the submarines to move into "safe" zones.[13] B-Dienst had broken Naval Cypher No 3 in February 1942 and by March was reading up to 80 per cent of the traffic, which continued until 15 December 1943. By coincidence, the British lost access to the Shark cypher and had no information to send in Cypher No 3 which might compromise Ultra.[14] In early September, Finnish Radio Intelligence deciphered a Soviet Air Force transmission which divulged the convoy itinerary and forwarded it to the Germans.[15]

Prelude

Luftflotte 5

In March 1942, Adolf Hitler issued a directive for a greater anti-convoy effort to weaken the Red Army and prevent Allied troops being transferred to northern Russia, preparatory to a landing on the coast of northern Norway. Luftflotte 5 (Generaloberst Hans-Jürgen Stumpff) was to be reinforced and the Kriegsmarine was ordered to put an end to Arctic convoys and naval incursions. The Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine were to work together with a simplified command structure, which was implemented after a conference; the Navy had preferred joint command but the Luftwaffe insisted on the exchange of liaison officers. Luftflotte 5 was to be reinforced by 2./Kampfgeschwader 30 (KG 30) and KG 30 was to increase its readiness for operations. A squadron of Aufklärungsflieger Gruppe 125 (Aufkl.Fl.Gr. 125) was transferred to Norway and more long-range Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Kondor patrol aircraft from Kampfgeschwader 40 (KG 40) were sent from France. At the end of March, the air fleet was divided.[16]

Fliegerführer Nord (Ost) [Oberst Alexander Holle], the largest command, was based at Kirkenes with 2./JG 5, 10.(Z)/JG 5, 1./StG 5 (Dive Bomber Wing 5) and 1.Fernaufklärungsgruppe 124 [1./(F) 124] (1 Squadron, Long Range Reconnaissance Wing 124) charged with attacks on Murmansk and Archangelsk as well as attacks on convoys. Part of Fliegerführer Nord (Ost) was based at Petsamo (5./JG 5, 6./JG 5 and 3./Kampfgeschwader 26 (3./KG 26), Banak (2./KG 30, 3./KG 30 and 1./(F) 22) and Billefjord (1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 125). Fliegerführer Lofoten (Oberst Hans Roth) was based at Bardufoss but had no permanently attached units, which were added according to events. At the start of the anti-shipping campaign only the coastal patrol squadrons 3./Küstenfliegergruppe 906 at Trondheim and 1./1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 123 at Tromsø were attached to Fliegerführer Lofoten. Fliegerführer Nord (West) was based at Sola and was responsible for the early detection of convoys and attacks south of a line from Trondheim westwards to Shetland and Iceland, with 1./(F) 22, the Kondors of 1./KG 40, short-range coastal reconnaissance squadrons 1./Küstenfliegergruppe 406 (1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406), 2./ Küstenfliegergruppe 406 (2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406) and a weather reconnaissance squadron.[17]

Luftwaffe tactics

As soon as information was received about the assembly of a convoy, Fliegerführer Nord (West) would send long-range reconnaissance aircraft to search Iceland and northern Scotland. Once a convoy was spotted aircraft were to keep contact as far as possible in the extreme weather of the area. If contact was lost its course at the last sighting would be extrapolated and overlapping sorties would be flown to regain contact. All three Fliegerführer were to co-operate as the convoy moved through their operational areas. Fliegerführer Lofoten would begin the anti-convoy operation east to a line from the North Cape to Spitzbergen Island, whence Fliegerführer Nord (Ost) would take over using his and Fliegerführer Lofoten's aircraft, which would to Kirkenes or Petsamo to stay in range. Fliegerführer Nord (Ost) was not allowed to divert aircraft to ground support during the operation. As soon as the convoy came into range, the aircraft were to keep up a continuous attack until the convoy docked at Murmansk or Archangelsk. From late March to late May the air effort against PQ 13, 14, 15 and QP 9, 10 and 11 had little effect, twelve sinkings out of 16 lost in QP convoys and two out of five sinkings from QP convoys being credited to the Luftwaffe; 166 merchant ships had sailed for Russia and 145 had survived the journey.[18]

Bad weather had been nearly as dangerous as the Luftwaffe, forcing 16 of the ships in PQ 14 to turn back. In April, the spring thaw grounded many Luftwaffe aircraft and in May bad weather led to contact being lost and convoys scattering, being impossible to find in the long Arctic night. When air attacks on convoys had taken place, the formations rarely amounted to more than twelve aircraft, greatly simplifying the task of convoy anti-aircraft gunners, who shot down several aircraft in April and May. Failings in liaison between the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine were uncovered and tactical co-operation greatly enhanced, Hermann Böhm (Kommandierender Admiral Norwegen) noting that in the operation against PQ 15 and QP 11, there were no problems in co-operation between aircraft, submarines and destroyers.[19] From 152 aircraft in January, reinforcements to Luftflotte 5 increased its strength to 221 front-line aircraft by March 1942.[17] By May Luftflotte 5 had 264 aircraft based around the North Cape in northern Norway, consisting of 108 Ju 88 long-range bombers, 42 Heinkel 111 torpedo-bombers, 15 Heinkel He 115 float-plane torpedo-bombers, 30 Junkers Ju 87 dive-bombers and 74 long range Focke Wulf 200s, Junkers 88s and Blohm & Voss BV 138s.[20]

German air-sea rescue

The Luftwaffe Sea Rescue Service (Seenotdienst) along with the Kriegsmarine, the Norwegian Society for Sea Rescue (RS) and ships on passage, recovered aircrew and shipwrecked sailors. The service comprised Seenotbereich VIII at Stavanger covering Stavanger, Bergen and Trondheim and Seenotbereich IX at Kirkenes for Tromsø, Billefjord and Kirkenes. Co-operation was as important in rescues as it was in anti-shipping operations if people were to be saved before they succumbed to the climate and severe weather. The sea rescue aircraft comprised Heinkel He 59 floatplanes, Dornier Do 18 and Dornier Do 24 seaplanes.[21]

Oberkommando der Luftwaffe (OKL, the high command of the Luftwaffe) was not able to increase the number of search and rescue aircraft in Norway, due to a general shortage of aircraft and crews, despite Stumpff pointing out that coming down in such cold waters required extremely swift recovery and that his crews "must be given a chance of rescue" or morale could not be maintained. After the experience of PQ 16, Stumpff gave the task to the coastal reconnaissance squadrons, whose aircraft were not usually engaged in attacks on convoys. They would henceforth stand by to rescue aircrew during anti-shipping operations.[21]

Cruiser and distant escorts

After a naval action on 2 May, the Admiralty judged that the threat from German destroyers had declined and that cruisers need not escort PQ 16 beyond Bear Island. HMS Nigeria (Admiral Harold Burrough, commander cruiser covering force) and its destroyers HMS Oribi, Onslow and Marne departed from Seidisfiord on 23 May with the escorting destroyers for PQ 16, ORP Garland, HMS Volunteer, Achates, Ashanti and Martin. The heavy cruisers HMS Kent, Norfolk and the light cruiser Liverpool arrived later from Hvalfjörður on the west coast of Iceland. The Admiralty anticipated that the main threat to PQ 16/QP 12 were the cruiser Admiral Scheer, which was at Narvik by 10 May and the heavy cruiser Lützow which arrived on 26 May, the oiler (Troßschiff) Dithmarschen, the destroyer Hans Lody and the torpedo boat T7. To guard against a sortie by the battleship Tirpitz the aircraft carrier Victorious, the battleships HMS Duke of York (Admiral John Tovey, commander distant covering force) and USS Washington, the heavy cruisers USS Wichita and HMS London with nine British and four US fleet destroyers were to patrol to the north-east of Iceland. Five British and three Soviet submarines were to patrol off Norway and the Russians promised to attack Luftwaffe airfields in northern Norway with 200 bombers of the Soviet Air Forces (Voyenno-Vozdushnyye Sily, VVS). (The Russians could only provide 20 bombers for an attack after the main German operation against the convoy had ended.)[22]

Convoy escorts

The 36 ships of PQ 16 (Convoy Commodore N. H. Gale RNR) the largest Arctic convoy yet, sailed from Hvalfjörður in Iceland on 21 May 1942; the departure was reported by a German spy in Reykjavik. Convoys had a standard formation of short columns, number 1 to the left in the direction of travel. Each position in the column was numbered; 11 was the first ship in column 1 and 12 was the second ship in the column; 21 was the first ship in column 2.[23] Ships in column sailed at intervals of 400 yd (370 m) until 1943, when the interval was increased to 600 yd (550 m) and then 800 yd (730 m) to cater for inexperienced captains reluctant to keep so close.[24] The convoy formed nine columns with a close escort of the minesweeper HMS Hazard and the naval trawlers St Elstan, Lady Madeleine, Northern Spray and the Free French Retriever, which had to return after three days, being too slow to keep up.[25]

The merchant ship SS Empire Lawrence a catapult aircraft merchant ship that carried a Hawker Hurricane fighter for air defence. On 23 May, HMS Alynbank, an auxiliary anti-aircraft cruiser, joined the convoy from Seyðisfjörður (Seidisfiord). A converted steamer, Alynbank was equipped with radar, four pairs of high-angle 4-inch guns with director control, two quadruple QF 2-pounder Mark VIII "pom-pom" guns and 20 mm Oerlikon guns with a Royal Navy crew and acting-captain Henry Nash in command.[25] Alynbank was accompanied by the corvettes Honeysuckle, Starwort, Hyderabad and the Free French Roselys.[26] The T-class submarine HMS Trident and the S-class submarine Seawolf joined the convoy, as did Force Q, the fleet oiler RFA Black Ranger and the Hunt class destroyer HMS Ledbury.[25] The Allied submarines P37, P46, P614, the Netherlands O-10, the Free French Minerve and the Soviet submarines S-102, Shch-422 and K-1 formed a flanking screen.[26][d]

Convoy

24 May

The cruiser covering force was spotted by a German reconnaissance aircraft at 7:00 p.m. on 24 May and at midnight ran into a thick fog. The cruisers and the destroyers Ashanti, Martin, Achates, Volunteer and Garland turned north-east to avoid collisions; in the murk, the destroyers separated for safety. Garland lost station and rejoined the cruisers as the other destroyers searched for the convoy. PQ 16 was having difficulties of its own and only avoided dispersal because of the radar carried by the escorts, the sets on Volunteer and Hyderabad in particular. The merchant ships moved through the fog sounding "course 080°, speed 6 kn" in Morse code on their sirens but the convoy was not able to regain formation until the evening. Inside the Arctic Circle there is perpetual daylight from May to July and patchy fog continued to hamper the crews, exhausting lookouts and watch-keepers. At about 5:00 a.m. the visibility improved and the cruisers joined the convoy in pairs between the central columns of the freighters. The 17th Destroyer Flotilla in Onslow placed his ships at the disposal of Commander Richard Onslow, the Captain (D) in Ashanti, the close escort commander.[28]

25 May

Ashanti had embarked a party of RAF airmen who spoke German and had high-frequency wireless receivers to eavesdrop on Luftwaffe R/T traffic. Sometimes the RAF men heard pilots on the ground talking to each other and later listened to their claims as they returned to their airfields. An FW 200 Kondor appeared at 6:00 a.m. and was fired on by a destroyer as the convoy zig-zagged. More fog was encountered and the zig-zagging was stopped and started again in the clear patches. The destroyers took on fuel from Black Ranger and then Force Q left the convoy. QP 12 crossed at about 2:00 p.m. and reported sighting a U-boat at 1:00 p.m.; at 3:00 p.m., Martin, on the starboard side of the convoy, spotted a U-boat and attacked, firing until the submarine dived, then depth-charged the area before returning to its station. The convoy sailed eastwards in a moderate sea breeze but the endless daylight continued to affect the crews above decks, making them more tense and fatigued.[29]

A BV 138 took over the shadowing from the Kondor and the first air attack began at 7:10 p.m. Several Ju 88s and 9 Heinkel 111 torpedo-bombers from 3./KG 26 (Hauptmann Eicke), six of which turned back due to the clear sky. The remaining Heinkels 111s attacked out of the sun and claimed one ship sunk and one damaged.[30] Empire Lawrence launched Pilot Officer May in its catapult Hurricane, who attacked the Heinkel 111s. May set one on fire and damaged another; he was wounded in the legs by return fire and his Hurricane was hit by anti-aircraft fire from one of the ships. Hay ditched his Hurricane in the path of the convoy, where he was picked up by Volunteer. The Heinkels dropped torpedoes, all of which missed and six Junkers Ju 88s dive-bombed. Hyderabad was near-missed and the US merchantman Carlton suffered a broken steam pipe. The anti-submarine trawler Northern Spray took Carlton in tow and turned back to Iceland, the pair arriving safely.[29] Six He 111s of 2./KG 26 and four He 115s of 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406 arrived later. British observers noticed that one of the He 115s circled after attacking, thought to be ready to rescue shot-down aircrew. The He 111s claimed one possible hit and five misses, the He 115s claimed one torpedo launched and three aircraft turning back due to the visibility.[30][e]

26 May

Low cloud grounded the bombers until just before midnight; 20 Ju 88s of III./KG 30 and seven He 111 torpedo-bombers of 3./KG 26 attacked the convoy with no result for the loss of two aircraft to anti-aircraft fire from the convoy and escorts. The He 111s claimed three ships hit and three damaged; fifteen of the Ju 88s reported failure to find the convoy and of the five which did, none reported a hit.[32] The convoy encountered drifting ice and in the conditions U-boat wolfpack was evaded but Asdic contacts were gained around 3:00 a.m. and depth-charged. At 3:05 a.m. Syros at the back of the seventh column was torpedoed by U-703 and nine of the crew were killed; the survivors were rescued by Haggard and Lady Madeleine.[33]

As the escorts depth-charged, Burroughs took the cruiser covering force and its destroyers to the north at 20 kn (23 mph; 37 km/h) to join QP 12. The anti-aircraft firepower of the force had been of great value and the departure was viewed as desertion by the merchant ship crews, especially the US and Soviet personnel. Torpedoes from U-436 and U-591 missed one of the merchant ships and Ashanti; U-boat sightings and attacks on them by the escorts occurred for the rest of the day. Shadowing aircraft remained in contact all day; at 6:00 p.m. seven He 111 torpedo-bombers of KG 26 and eleven Ju 88s of KG 30 attacked and were driven off by the anti-aircraft fire of the convoy and escorts. During the evening, 100 nmi (120 mi; 190 km) west of Bear Island, the convoy made a turn to the south-east, almost direct towards Banak, because of pack-ice.[33]

27 May

Morning

At 3:20 a.m. German aircraft made another abortive attack. The weather had turned fair and clear with thin layers of cloud. The convoy hugged the pack ice and by mid-morning was able to change course to the east but the diversion had brought PQ 16 closer to the German air bases in northern Norway. Luftflotte 5 made a maximum effort, co-ordinating attacks in waves over about ten hours. Six He 111 torpedo bombers of 2./KG 26 attacked first, five dropping torpedoes and one returning with its torpedoes. Four Ju 88s from III./KG 30 made decoy torpedo runs as many other Ju 88s bombed and claimed several hits.[32] Broken cloud at 3,000 ft (910 m) and a thin layer of stratus cloud at 1,500 ft (460 m) were used by dive-bombers to hide their approach and were unseen until the last moment. With the cruiser covering force gone, only Alynbank and Martin could elevate their main armament for anti-aircraft action; the other destroyers and corvettes had to wait until aircraft were within range of their lighter guns.[34]

Noon

The crew of Alynbank counted 108 attacks during the day and near noon, Stari Bolshevik, carrying ammunition and vehicles, was hit forward by a bomb and set on fire. The crew fought the fire as ready-use ammunition for the gun at the bow began to explode; the gun fell through the deck into the forepeak. The ship lost speed and while under air attack, Martin lowered its whaler and sent Surgeon-Lieutenant R. Ransome Wallis across. The doctor and whaler crew evacuated three seriously wounded Soviet sailors to Martin for emergency surgery. Roselys assisted Stari Bolshevik to put out the fire and the ship resumed position, for the next two days beneath a plume of smoke.[34]

Afternoon

Four bombs were dropped close to Garland and the first one exploded on contact with the sea, setting off the other three, showering Garland with splinters, killing 25 crewmen and wounding 43. A and B guns were knocked out along with an Oerlikon, some smoke floats were set alight and dumped overboard and the wireless aerials were brought down, requiring Lady Madeleine to sail alongside to relay messages from Ashanti. Another air attack began at 1:20 p.m. and hit Alamar; a few minutes later Mormacsul was hit and caught fire. The ships lost way and Starwort stood by to rescue survivors, the two ships sinking at 1:30 p.m. Three Ju 88s bombed Empire Lawrence and hit No. 2 hold. A bomb went through the side of the hull and exploded, making a hole and causing a list to port, the bow to settle and the ship to lose speed.[35]

The lifeboats had already been swung out and as the ship stopped they were lowered. As soon as the ship had been hit Lady Madeleine and Hyderabad had turned towards it and then another attack hit Nos. 4 and 5 holds and the magazine. As Lady Madeleine drew near, Empire Lawrence broke into halves and the ship disappeared in a cloud of smoke. The starboard lifeboat was blown clear and capsized; the port lifeboat was shattered along with several of its occupants and then German bombers strafed the wreckage. Lady Madeleine launched its boat and swiftly recovered survivors, most from the starboard lifeboat. Hyderabad saved another 30 crewmen, many hanging onto smashed wood or oil drums for a considerable time in the freezing water. The rescue ships returned to the convoy after no more survivors could be seen.[35]

Empire Baffin and City of Joliet were shaken by near misses, Joliet being abandoned temporarily. Thinner ice was encountered and at 2:35 p.m. course was altered north-north-east 80 nmi (92 mi; 150 km) south-east of Bear Island. Some of the survivors taken on board by Lady Madeleine needed urgent medical attention and Martin came so close alongside that Ransome Wallis was able to jump the gap. The wounded were passed over to Martin in Neil Robertson stretchers, in something of a rush, due to an attack by eight Ju 88s.[36][f]

Evening

All of the ships were running short of ammunition but a lull in the attacks occurred until 7:35 to 8:00 p.m. when seven He 111s attacked with torpedoes to no effect. German aircraft resumed dive-bombing and torpedo-bombers used this as a diversion. The German aircrews claimed five ships sunk and five damaged but three Ju 88s were shot down.[32] The lack of ammunition left some freighters with no means of engaging the bombers. Empire Purcell was hit twice by bombs in no. 2 hold, set on fire and damaged by two near misses. The bunker bulkhead collapsed, depositing its coal into the stokehold and an Oerlikon gunner was knocked off the bridge. The crew began to abandon ship but some of the ropes for one lifeboat had frozen, leading it to drop at one end, tipping the men in the boat into the sea, where eight were killed. Men trapped underneath were rescued one at a time by Able Seaman William Thompson. Four crewmen got the other lifeboat away just before the ship exploded with a huge bang; Hyderabad rescued the survivors.[37]

Lowther Castle was hit by two torpedoes from a He 111 dropped at long range; the crew had tried to comb the tracks but the ship was hit on the port side, setting the contents of No. 2 hold alight. The shock of the torpedo explosions disabled the steering; engines were stopped and an abandon ship was ordered. The disaster on Empress Purcell had broken the morale of some of the crew and one of the lifeboats was dropped into the water throwing its occupants into the sea but all but the captain were rescued. The ship was strafed and dive-bombed as Honeysuckle rescued the survivors; Lowther Castle burned for another eight hours before exploding astern of the convoy in a big plume of smoke. As Hyderabad had recovered survivors from Empress Purcell it had been ordered to transfer ammunition from John Randolph to Hybert and Pieter de Hoogh also requested replenishment.[38]

Onslow became concerned at the ammunition shortages on some of the US freighters and got the crew of John Randolph to load ammunition boxes on the after-deck. The ship was out of station and while looking for it, another request for ammunition was received from Ironclad; Hyderabad managed to transfer the ammunition from John Randolph. Ocean Voice, carrying the convoy commodore, was hit by a bomb which blew a hole in the hull close to the waterline near the forward hold and caused a fire. The ship kept position as the crew fought the fire but Gale had to hand over to the vice-commodore, the captain of Empire Selwyn, J. T. Hair. The attacks ended and City of Joliet was re-boarded, still down by the head and falling behind. Ocean Voice was expected to sink and Garland was so badly damaged that it was ordered to sail independently; Onslow gave orders for ammunition conservation.[38]

28–29 May

City of Joliet sank early in the morning of 28 May and as the temperature dropped, icebergs reappeared and ice formed on the ship's superstructures. Martin conducted burials at sea as Stari Bolshevik and Ocean Voice plumed smoke. In the distance, a BV 138 continued to circle the convoy and air attacks began again at 9:30 a.m. Twelve Ju 88s and five He 115s of 1./Kü.Fl.Gr 906 flew against the convoy and two of the He 115s claimed a ship found at a standstill, not in the convoy; two failed to find ships and one of the He 115s was shot down.[39] The convoy had been met by the Soviet destroyers Grozni, Sokrushitelny and Valerian Kuybyshev which were equipped with excellent anti-aircraft armament and supplemented those ships in the convoy which still had ammunition, helping to drive off the air attacks. In the early morning of 29 May another attack, by seven He 111 torpedo-bombers of 2./KG 26 and several Ju 88s attacked; the JU 88s has no effect and two of the He 111s turned back with technical failures; two released torpedoes as Ju 88s made decoy runs but the attack was a failure; three hits were claimed but these were erroneous.[39]

During the evening, when PQ 16 was 140 nmi (160 mi; 260 km) north-east of the Kola Inlet, the eastern local escort (1st Minesweeping Flotilla, Captain John Crombie) comprising the minesweepers Bramble, Leda, Seagull, Niger, Hussar and Gossamer arrived. The flotilla was to escort the six ships bound for Archangelsk along with Martin and Alynbank, depriving PQ 16 of its best long-range radars, just as the convoy was about to enter an area patrolled by U-boats. Onslow organised a U-boat screen, despite this reducing the concentration of anti-aircraft fire generated by merchant ships and escorts. At 11:20 p.m. 18 Ju 87s and Ju 88s dive-bombed PQ 16 and 15 Ju 88s attacked the detached ships whilst both sections were still in sight; both raids were abortive and two Ju 88s were shot down.[39] Aircraft of the Soviet Northern Fleet intercepted the raiders.[40][41][g]

30 May – 1 June

The section of the convoy bound for Archangelsk passed through the Gorlo (throat) into the White Sea. As PQ 16 headed for Murmansk it was attacked three times but no ships were hit and two Ju 88s were shot down. At 1:00 p.m. Russian Hurricanes began to escort the convoy and at 4:00 p.m. the convoy entered the Kola Inlet. The detached section reached the estuary of the Northern Dvina and met the icebreaker Stalin off Sozonoya, spending the next forty hours following it in line astern, during which they were attacked by Ju 87 dive-bombers to no effect. Martin could only reply with small-arms fire and armour-piercing ammunition from its main guns but Alynbank managed to fight off the attackers. Martin diverted to Vaenga in Kola Bay to replenish ammunition, arriving on 1 June. The ships docked at Bakaritsa Quay, 2 mi (3.2 km) upstream of Archangelsk on the opposite bank.[43]

Aftermath

Analysis

Stephen Roskill, the British official historian, wrote in 1962 that the empty ships of QP 12, on a simultaneous return journey from Russia, had a comparatively uneventful passage; one Russian ship had to turn back and the rest reached Reykjavik on 29 May. Fifty ships had sailed in the convoys, two had turned back and seven had been sunk. Tovey, the commander of the Home Fleet, wrote that "This success was beyond expectation." and Admiral Karl Dönitz, the commander of the German U-boat arm (Befehlshaber der Unterseeboote) acknowledged that the convoy escorts had thwarted the U-boats. An exaggerated claim by the Luftwaffe that PQ 16 had been sunk, led Dönitz to the view that aircraft would be more effective in anti-convoy operations during the summer. Onslow, the British escort commander, wanted more CAM ships or escort carriers and more anti-aircraft ships on Arctic convoys because anti-aircraft defences had become just as important as the defence against U-boats and surface ships, given the greater number of Luftwaffe aircraft based in northern Norway.[20]

In 2001 Adam Claasen wrote that the losses inflicted on PQ 16 amounted to half the number of ships sunk by the Luftwaffe during April and May, the reinforcement of Luftflotte 5 and the longer hours of daylight, putting Arctic convoys at an increasing disadvantage. Hitler anticipated an attempted landing in Norway and ordered that a maximum effort be made against the ships. Stumpff committed the largest air effort against an Arctic convoy since operations had begun.[19] Luftflotte 5 had refined its anti-shipping tactics and used the Golden Comb (Goldene Zange) tactic of combined dive-bombing and torpedo-bombing attacks, the torpedo-bombers flying in line abreast and releasing their torpedoes in a salvo. The torpedo-bombers had conducted their first operation against PQ 15 and sunk three ships. The Germans sent 101 Ju 88s and seven He 111 torpedo-bombers against PQ 16 and claimed nine ships sunk, six more so badly damaged that they were claimed as probably sunk and sixteen merchant ships damaged. The Luftflotte 5 diarist wrote,

Thus supplies to Russia from Britain and America have been dealt a severe blow. [27 May 1942].... the correct combination of torpedo and diving attacks could bring about special success at the cost of modest losses. [1 June 1942][44]

and the Kriegsmarine staff wrote "...the enemy has learned unmistakably what risks he takes by bringing strong expeditionary forces into the range of the Luftwaffe." under the impression that the convoy had been sunk but only five ships had been lost to the bombers, one to a torpedo-bomber and one damaged and forced to turn back. The U-boats had been at a disadvantage in the perpetual daylight and were easily spotted and repulsed by the convoy escorts.[45]

In 2004, Richard Woodman wrote that PQ 16 had mainly had to defend itself from air attack and that in Onslow's judgement, despite the exemplary performance of Alynbank, most of the escorts were lacking in anti-aircraft firepower. One CAM ship was insufficient and the second long-range radar in Empire Lawrence had been unserviceable. Onslow recommended to the Admiralty that convoys should be furnished with more anti-aircraft weapons and ammunition, an ammunition magazine should be created at Vaenga and that an escort carrier and specialist rescue vessels should accompany convoys. Onslow also wanted faster submarine escorts and fire-fighting tugs. A tanker, SS Hopemount, refuelled the escorts, Garland being the first to arrive. Tovey wrote that the convoy had been delivered to Russia through the determination of the escorts and merchant crews.[46] The Senior British Naval Officer, North Russia Rear-Admiral Richard Bevan delivered congratulations from the Admiralty. The heavy lift ships from Convoy PQ 16, including SS Empire Elgar, stayed at Archangelsk and Molotovsk unloading ships for over 14 months.[47]

Dönitz wrote in his war diary,

My opinion as to the small chances of success for U-boats against convoys during the northern summer...has been confirmed by experience with PQ 16....This must be accounted a failure when compared with the results of the anti-submarine activity for the boats operating.[48]

Dönitz thought that the Luftwaffe would be more effective during the summer months, somewhat misled by the exaggerated claims of the bomber and torpedo-bomber pilots, despite the convoy being shadowed for much of the journey by reconnaissance aircraft.[48]

Casualties

R. Ransome Wallis, the surgeon lieutenant in Martin, wrote an account of PQ 16 in 1973. The sick bay was under the aft 4.7-inch turret, the 4-inch AA gun was forward and just to the rear were two 20 mm Oerlikon guns, twin Vickers .5-inch machine-guns and the depth charge throwers. During air attacks, the sound from the guns and the empty cartridge cases of the 4.7-inch guns rattling about made the sick bay exceedingly noisy. There was a Sick Berth Attendant (SBA) but during action stations, he tended to disappear to the magazines and other busy parts of the ship to help. Ransome Wallis discovered that a trained Leading Sick Berth Attendant (LSBA) working as the ship's quartermaster whom the captain released to the sick bay. Ramsome Wallis noted that after HMS Punjabi had been run down and sunk by the battleship HMS King George V it had been difficult to rescue survivors covered in oil and the crew of Martin adopted a rope harness with a loop at the back to make it easier to pull them out of the water.[49]

When at action stations many sailors had been seriously injured by explosions throwing them upwards into the deck above and Ransome Wallis followed the general order to lie down instead until he realised, somewhat to his embarrassment, that no-one did this on Martin. During raids Ransome Wallis went on deck to watch and give a running commentary to the occupants of the sick bay.[49] Underwater explosions from bomb near-misses made a great clanking noise which was highly stressful to those crewmen working below deck. Ransome Wallis witnessed the sinking of Syros. A trawler rescued many members of the crew but nine men were killed. For two days U-boats kept surfacing in the distance. The only ships fast enough to overhaul them were the destroyers and Martin took part in the chases. On one occasion Martin and 'Achates hunted and depth-charged a U-boat, that they had forced to submerge then it surfaced between the destroyers, fired a torpedo at Achates and submerged again. On 27 May Ransome Wallis watched four bombs from a Ju 88 drop close to Martin, which caused internal damage. When Stari Bolshevik was hit, Ransome Wallis was ordered across in a whaler with five crewmen to evacuate the seriously wounded. The captain of Martin stressed that both ships would have to stop for the whaler and that the matter must be concluded speedily.[50]

Ransome Wallis took the SBA and two Neil Robertson stretchers; the Russian ship was 300 yd (270 m) away and as the whaler was rowed across more German aircraft appeared and Stari Bolshevik got under way. Everyone in the whaler worked an oar as German bombs fell around, soaking the occupants, who rapidly caught up with the ship and tied onto a rope ladder on the port side. The stretchers were pulled up onto the deck and Ransome Wallis took three wounded into the whaler in the stretchers and three walking wounded; five crew of Stari Bolshevik had been killed. Martin appeared as the bombers flew away and recovered the whaler; the wounded were rushed to the sick bay and Ransome Wallis found that each of the wounded had several injuries, particularly from bomb splinters. It was fairly easy to remove the splinters but one man had puncture wounds in his lungs. Somewhat to Ransome Wallis's surprise, the LSBA fainted and Ransome Wallis discovered that he could not stand the sight of blood. Ransome Wallis was sympathetic but had to swap back the LSBA and the SBA when there was a lull in the air attacks, then managed to set a compound fracture. Ransome Wallis decided that it was impossible to work on the wounded during attacks because of the din from the guns and explosions in the water. The wounded seemed unaffected by morphia but were stoical.[51]

During the afternoon, Empire Lawrence was sunk and only 16 survivors were rescued, most being wounded and claiming that they had been machine-gunned while in the water. Empire Baffin and City of Joliet were bombed followed by Garland being seriously damaged by airbursts that swept the upper works with bomb splinters, killing 25 crewmembers and wounding another 43. During the afternoon there was another lull and Ransome Wallis operated on the Russians from Stari Bolshevik; he was then warned that Lady Madeleine would be transferring more wounded to Martin. As soon as the trawler came alongside, Ransome Wallis jumped aboard with a small party and two stretchers to see eight wounded men, three seemingly seriously wounded. One man has six fractures in his leg, a young man was paralysed from the waist down and two men had severe head wounds. Two of the men were put on the stretchers and transferred to Martin but Ju 88s appeared and resumed the bombing. The rest of the wounded had to be rushed across so that Martin could get under way. Two of the least seriously wounded were placed on stretchers in the sick bay and six were put up in Ransome Wallis's and the captain's cabins.[52]

The cabins were closer to the water line and bomb explosions in the water made much more noise than in the sick bay. The wounded felt trapped and began to scream and shout, which spread until they were ordered to stop it, however dreadful their ordeal, to stop the panic from spreading. More wounded were taken on board from Empire Lawrence, who thought that the only lifeboat that got away was destroyed by machine-gun fire. The second engineer had a depressed fracture of the skull and as he was treated they realised that he was one of Ransome Wallis's patients from before the war. During the evening the German attacks resumed with great intensity and Empire Purcell exploded in a great flash but the crew had abandoned ship before the explosion and most survived. The attacks went on and some men on Martin began to succumb to the strain, one man having alternating bouts of shivering and weeping. Ransome Wallis was asked to show himself in the engine and boiler rooms to encourage the stokers and Engine Room Artificers and found the loud hammering of bombs and depth charge explosions in the water just as frightening. When Ransome Wallis returned to the wounded he tried to rig a drip into the sailor with a fractured spine but when another attack began the sailor pulled out the needle and resisted when he was being tied down to administer the drip, leading Ransome Wallis to stop.[53]

The effect of explosions caused extensive internal bruising and bleeding which was often fatal. Early on 28 May the young sailor with the leg fractures died and was buried at sea. The air alarm sounded again but fog hid the convoy and Ransome Wallis heard aircraft fly low, apparently searching for the convoy, then fly away. The sick bay went quiet as the gunners above had cleared away the shell cases and the morphia administered to the wounded appeared to be taking effect. During the afternoon the young sailor with the fractured spine died and it was found that a bomb splinter had left a small entry wound in his back but caused severe spinal damage further inside; a man with a severe head injury died soon afterwards. More air raids occurred but Soviet fighters intercepted them and the convoy reached the Kola Inlet; Martin docked at Vaenga.[54] At least 43 sailors were killed, 43 were wounded and 471 men were rescued from ships in PQ 16. German sources show two U-boats were damaged and that three Ju 88s with two-man crews were shot down.[55] Harold Thiele (2004) recorded five Ju 88s and one He 115 shot down.[56]

In media

- In his book The Year of Stalingrad (1946) the British war correspondent Alexander Werth described his experience of Convoy PQ 16 on SS Empire Baffin, which was bombed and damaged by near misses but reached Murmansk under its own power.[57]

- In his 1973 memoir, Two Red Stripes the surgeon on Martin, R. Ransome Wallis, devoted a chapter to his account of PQ 16.[58]

Convoyed ships

| Name | Flag | GRT | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alamar | 5,689 | Sunk by aircraft | |

| Alcoa Banner (1919) | 5,035 | Alcoa Steamship Company reached port | |

| American Press (1920) | 5,131 | reached port | |

| American Robin (1919) | 5,172 | reached port | |

| Arcos (1918) | 2,343 | reached port | |

| Atlantic (1939) | 5,414 | reached port | |

| RFA Black Ranger | 3,417 | Ranger-class fleet support oiler with 2,600 long tons (2,600 t) fuel oil capacity | |

| Carlton (1920) | 5,127 | Damaged by near misses and towed back to Iceland by Northern Spray | |

| Chernyshevski (1919) | 3,588 | reached port | |

| City Of Joliet (1920) | 6,167 | Sunk by aircraft | |

| City Of Omaha (1920) | 6,124 | reached port | |

| Empire Baffin (1941) | 6,978 | Damaged by near-misses, reached port | |

| Empire Elgar (1942) | 2,847 | heavy-lift ship, reached port | |

| Empire Lawrence (1941) | 7,457 | Carried one catapult-launched Hawker Sea Hurricane; sunk by aircraft | |

| Empire Purcell (1942) | 7,049 | Sunk by aircraft | |

| Empire Selwyn (1941) | 7,167 | Convoy vice-commodore's vessel reached port | |

| Exterminator (1924) | 6,115 | Owned by US War Shipping Administration reached port | |

| Heffron (1919) | 7,611 | reached port | |

| Hybert (1920) | 6,120 | reached port | |

| John Randolph (1941) | 7,191 | reached port | |

| Lowther Castle (1937) | 5,171 | Sunk by aircraft (aerial torpedo) | |

| Massmar (1920) | 5,828 | reached port | |

| Mauna Kea (1919) | 6,064 | reached port | |

| Michigan (1920) | 6,419 | reached port | |

| Minotaur (1918) | 4,554 | reached port | |

| Mormacsul (1920) | 5,481 | Sunk by aircraft | |

| Nemaha (1920) | 6,501 | reached port | |

| Ocean Voice (1941) | 7,174 | Convoy commodore's vessel damaged by bomb, reached port | |

| Pieter De Hoogh (1941) | 7,168 | reached port | |

| Revolutsioner (1936) | 2,900 | reached port | |

| Richard Henry Lee (1941) | 7,191 | reached port | |

| Shchors (1921) | 3,770 | reached port | |

| Stari Bolshevik (1933) | 3,974 | bomb damage, reached port | |

| Steel Worker (1920) | 5,685 | Reached Murmansk, struck mine and sank[60] | |

| Syros (1920) | 6,191 | Sunk by U-703 | |

| West Nilus (1920) | 5,495 | reached port | |

| HMS Alynbank | 5,000 | Auxiliary anti-aircraft cruiser, escort 23–30 May, reached port[10] |

Close convoy escort

| Name | Flag | Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| HMS Hazard | Minesweeper | 21–30 May; Ocean Escort | |

| HMS Lady Madeleine | ASW trawler | 21 May; Western Local Escort | |

| HMS St Elstan | ASW trawler | 21 May; Western Local Escort | |

| HMS Retriever | ASW trawler | 21–25 May; Western Local Escort | |

| HMS Northern Spray | ASW trawler | 21–26 May; Western Local Escort | |

| HMS Achates | Destroyer | 23–30 May; Ocean Escort | |

| HMS Ashanti | Destroyer | 23–30 May; Ocean Escort Senior Officer Escort | |

| HMS Martin | Destroyer | 23–30 May; Ocean Escort | |

| HMS Volunteer | Destroyer | 23–30 May; Ocean Escort | |

| ORP Garland | Destroyer | 23–27 May; Ocean Escort | |

| HMS Honeysuckle | Corvette | 23–30 May; Ocean Escort | |

| HMS Roselys | Corvette | 23–30 May; Ocean Escort | |

| HMS Starwort | Corvette | 23–30 May; Ocean Escort | |

| HMS Hyderabad | Corvette | 23–30 May; Ocean Escort | |

| HMS Seawolf | Submarine | 23–29 May; Ocean Escort | |

| HMS Trident | Submarine | 23–29 May; Ocean Escort | |

| HMS Bramble | Minesweeper[h] | 28–30 May; Eastern Local Escort | |

| HMS Gossamer | Minesweeper | 28–30 May; Eastern Local Escort | |

| HMS Leda | Minesweeper | 29–30 May; Eastern Local Escort | |

| HMS Seagull | Minesweeper | 28–30 May; Eastern Local Escort | |

| Grozny | Destroyer | 28–30 May; Eastern Local Escort | |

| Valerian Kuybyshev | Destroyer | 28–30 May; Eastern Local Escort | |

| Sokrushitelny | Destroyer | 28–30 May; Eastern Local Escort | |

| RFA Black Ranger | Fleet Oiler | Force "Q". Detached on 27 May to return to Scapa Flow | |

| HMS Ledbury | Destroyer | 23–30 May; Force "Q", escorted Black Ranger |

Cruiser covering force

| Name | Flag | Ship type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| HMS Kent | Heavy cruiser | 23–26 May | |

| HMS Norfolk | Heavy cruiser | 23–26 May | |

| HMS Liverpool | Light cruiser | 23–26 May | |

| HMS Nigeria | Light cruiser | 23–26 May | |

| HMS Marne | Destroyer | 23–26 May | |

| HMS Onslow | Destroyer | 23–26 May | |

| HMS Oribi | Destroyer | 23–26 May |

Distant covering force

| Name | Flag | Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| HMS Victorious | Aircraft carrier | 23–29 May | |

| HMS Duke of York | Battleship | 23–29 May | |

| USS Washington | Battleship | 23–29 May | |

| USS Wichita | Heavy cruiser | 23–29 May | |

| HMS London | Heavy cruiser | 23–29 May | |

| HMS Blankney | Escort destroyer | 23–29 May | |

| HMS Eclipse | Destroyer | 23–29 May | |

| HMS Faulknor | Destroyer | 23–29 May | |

| HMS Fury | Destroyer | 23–29 May | |

| HMS Icarus | Destroyer | 23–29 May | |

| HMS Intrepid | Destroyer | 23–29 May | |

| HMS Lamerton | Escort destroyer | 23–29 May | |

| HMS Middleton | Escort destroyer | 23–29 May | |

| HMS Wheatland | Escort destroyer | 23–29 May | |

| USS Mayrant | Destroyer | 24–29 May | |

| USS Rhind | Destroyer | 24–29 May | |

| USS Rowan | Destroyer | 24–29 May | |

| USS Wainwright | Destroyer | 24–29 May |

See also

- "HMS Ulysses" 1955 novel by Alastair MacLean

- Finnish radio intelligence intercepted planned route of the convoy.

- List of shipwrecks in May 1942

Notes

- ^ In October 1941, the unloading capacity of Archangel was 300,000 long tons (300,000 t), Vladivostok (Pacific Route) 140,000 long tons (140,000 t) and 60,000 long tons (61,000 t) in the Persian Gulf (for the Persian Corridor route) ports.[4]

- ^ The codebooks were carried in a weighted bag which was to be dumped overboard to prevent capture.[6]

- ^ By the end of 1941, 187 Matilda II and 249 Valentine tanks had been delivered, comprising 25 per cent of the medium-heavy tanks in the Red Army, making 30–40 per cent of the medium-heavy tanks defending Moscow. In December 1941, 16 per cent of the fighters defending Moscow were Hawker Hurricanes and Curtiss Tomahawks from Britain; by 1 January 1942, 96 Hurricane fighters were flying in the Soviet Air Forces (Voyenno-Vozdushnye Sily, VVS). The British supplied radar apparatuses, machine tools, ASDIC and other commodities.[7]

- ^ The 15 returning ships of QP 12 departed from Kola Inlet, also on 21 May, guided out to sea by four British minesweepers.[26] The convoy was led by the destroyer HMS Inglefield with the destroyers HMS Escapade, Venomous, HMS Boadicea, Badsworth and the Norwegian HNoMS St. Albans, the trawlers Cape Palliser, Northern Pride, Northern Wave and Vizalma, the auxiliary anti-aircraft cruiser HMS Ulster Queen and the CAM ship SS Empire Morn. Two Russian destroyers accompanied the convoy as far as longitude 30° East. On 22 May a ship from QP 12, unable to maintain speed, turned back to Kola.[27]

- ^ Despite good visibility, QP 12 was not spotted by a German reconnaissance aircraft until 25 May. Just before midday, an FW 200 Kondor, a BV 138 and two Ju 88s arrived. Empire Morn launched its Hurricane, flown by Flying Officer John Kendal (RAFVR). As soon as Kendal was airborne he lost touch with his fighter controller, Sub-Lieutenant P. G. Mallett, in Empire Morn when his R/T transmitter went unserviceable, although his receiver continued to work. Kendal lost sight of the BV 138 in cloud and attacked a Ju 88, chasing it along the length of the convoy before firing two long bursts of machine-gun fire. The engines of the Ju 88 emitted smoke and the crew jettisoned their bombs then the aircraft crashed into the sea. The other German aircraft showed no sign of attacking and Kendal prepared to ditch near Boadicea but the ship was nearing low rain clouds. Mallett recommended ditching near one of the rear convoy escorts. The Hurricane emerged from cloud and circled towards Badsworth then Kendal waggled his wings, indicating that he was going to parachute. Kendal climbed back into the cloud, the deck crews on the ships heard the Hurricane engine cut and saw the aircraft fall out of the cloud and into the sea. A moment later Kendal emerged from the cloud but his parachute only began to open 50 ft (15 m) above the sea. Kendal was picked up by Badsworth but had been mortally injured and died ten minutes later. Kendal had deterred the other aircraft from attacking and may have protected temporarily PQ 16 from detection, the convoys crossing three hours later.[31]

- ^ Martin was already full of survivors; during the voyage, 471 men were rescued from the seven ships of PQ 16 that were sunk.[37]

- ^ QP 12 was not attacked, the German operation against PQ 16 taking priority; sailing through thick fog prevented its detection by U-boats. QP 12 reached Iceland on 29 May.[42]

- ^ Called "fleet minesweeping sloops", they were used with the Arctic convoys as minesweepers and anti-submarine escorts. The ships sailed with convoys and remained in Russia until the next winter then returned with a QP convoy in the spring.[62]

Footnotes

- ^ a b Woodman 2004, p. 22.

- ^ a b c Hancock & Gowing 1949, pp. 359–362.

- ^ a b Claasen 2001, pp. 195–197.

- ^ Howard 1972, p. 44.

- ^ Woodman 2004, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Woodman 2004, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Edgerton 2011, p. 75.

- ^ & Roskill 1962, p. 119.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 144–145.

- ^ a b Woodman 2004, p. 145.

- ^ a b Macksey 2004, pp. 141–142.

- ^ a b Hinsley 1994, pp. 141, 145–146.

- ^ Kahn 1973, pp. 238–241.

- ^ Budiansky 2000, pp. 250, 289.

- ^ FIB 1996.

- ^ Claasen 2001, pp. 199–200.

- ^ a b Claasen 2001, pp. 200–201.

- ^ Claasen 2001, pp. 201–202.

- ^ a b Claasen 2001, p. 202.

- ^ a b Roskill 1962, p. 132.

- ^ a b Claasen 2001, pp. 203–205.

- ^ Woodman 2004, p. 146.

- ^ Woodman 2004, p. 104; Ruegg & Hague 1993, pp. 31, inside front cover.

- ^ Hague 2000, p. 27.

- ^ a b c Woodman 2004, pp. 145–146.

- ^ a b c Rohwer & Hümmelchen 2005, p. 167.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 145–146, 149.

- ^ Woodman 2004, p. 148.

- ^ a b Woodman 2004, pp. 149–150.

- ^ a b Thiele 2004, p. 36.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 147–148.

- ^ a b c Thiele 2004, p. 37.

- ^ a b Woodman 2004, pp. 150–151.

- ^ a b Woodman 2004, pp. 151–152.

- ^ a b Woodman 2004, pp. 152–153.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 153–154.

- ^ a b Woodman 2004, p. 154.

- ^ a b Woodman 2004, pp. 155–156.

- ^ a b c Thiele 2004, p. 38.

- ^ Woodman 2004, p. 156–167.

- ^ Walling 2012, p. 146.

- ^ Woodman 2004, p. 149.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Claasen 2001, p. 203.

- ^ Claasen 2001, pp. 203–204.

- ^ Woodman 2004, p. 158.

- ^ Woodman 2004, p. 157.

- ^ a b Woodman 2004, p. 159.

- ^ a b Ransome Wallis 1973, pp. 83–85.

- ^ Ransome Wallis 1973, pp. 91–94.

- ^ Ransome Wallis 1973, pp. 91–96.

- ^ Ransome Wallis 1973, pp. 96–98.

- ^ Ransome Wallis 1973, pp. 96–104.

- ^ Ransome Wallis 1973, pp. 98–104.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 144–159; Walling 2012, p. 150.

- ^ Thiele 2004, pp. 36–38.

- ^ Werth 1946, pp. 1–44.

- ^ Ransome Wallis 1973, pp. 1–144.

- ^ a b c Ruegg & Hague 1993, p. 37.

- ^ Ruegg & Hague 1993, p. 38.

- ^ Ruegg & Hague 1993, pp. 37–28.

- ^ , Ruegg & Hague 1993, p. 16.

References

- Budiansky, S. (2000). Battle of Wits: The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War II. New York: The Free Press (Simon & Schuster). ISBN 0-684-85932-7 – via Archive Foundation.

- Claasen, A. R. A. (2001). Hitler's Northern War: The Luftwaffe's Ill-fated Campaign, 1940–1945. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-1050-2.

- Edgerton, D. (2011). Britain's War Machine: Weapons, Resources and Experts in the Second World War. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9918-1.

- Hague, Arnold (2000). The Allied Convoy System, 1939–1945: Its Organization, Defence and Operation. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-019-9.

- Hancock, W. K.; Gowing, M. M. (1949). Hancock, W. K. (ed.). British War Economy. History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Civil Series. London: HMSO. OCLC 630191560.

- Hinsley, F. H. (1994) [1993]. British Intelligence in the Second World War: Its Influence on Strategy and Operations. History of the Second World War (2nd rev. abr. ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-630961-7.

- Howard, M. (1972). Grand Strategy: August 1942 – September 1943. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. IV. London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-630075-1 – via Archive Foundation.

- Kahn, D. (1973) [1967]. The Codebreakers: The Story of Secret Writing (10th abr. Signet, Chicago ed.). New York: Macmillan. LCCN 63-16109. OCLC 78083316.

- Macksey, K. (2004) [2003]. The Searchers: Radio Intercept in two World Wars (Cassell Military Paperbacks ed.). London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-36651-4.

- Ransome Wallis, R. (1973). Two Red Stripes. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-0461-0.

- Rohwer, Jürgen; Hümmelchen, Gerhard (2005) [1972]. Chronology of the War at Sea, 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two (3rd rev. ed.). London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-257-7.

- Roskill, S. W. (1962) [1956]. The Period of Balance. History of the Second World War: The War at Sea 1939–1945. Vol. II (3rd impr. ed.). London: HMSO. OCLC 174453986. Retrieved 4 June 2018 – via Hyperwar.

- Ruegg, Bob; Hague, Arnold (1993) [1992]. Convoys to Russia (2nd rev. exp. pbk. ed.). Kendal: World Ship Society. ISBN 978-0-905617-66-4.

- Thiele, Harold (2004). Luftwaffe Aerial Torpedo Aircraft and Operations in World War Two. Ottringham: Hikoki. ISBN 978-1-902109-42-8.

- Walling, M. G. (2012). Forgotten Sacrifice: The Arctic Convoys of World War II (e-Pub e-book ed.). Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-78200-290-1.

- Werth, A. (1946). The Year of Stalingrad: An Historical Record and a Study of Russian Mentality, Methods and Policies (online scan ed.). London: Hamish Hamilton. OCLC 901982780.

- Woodman, Richard (2004) [1994]. Arctic Convoys 1941–1945. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-5752-1.

Websites

- "Birth of Radio Intelligence in Finland and its Developer Reino Hallamaa". Pohjois–Kymenlaakson Asehistoriallinen Yhdistys Ry (North-Karelia Historical Association Ry) (in Finnish). 1996. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

Further reading

- Bekker, Cajus (1973) [1964]. The Luftwaffe War Diaries [Angriffshöhe 4000]. Translated by Ziegler, F. (4th US ed.). New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-22674-7. LCCN 68-19007.

- Blair, Clay (1996). Hitler's U-Boat War: The Hunters 1939–42. Vol. I. London: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-35260-8.

- Kemp, Paul (1993). Convoy! Drama in Arctic Waters. London: Arms and Armour Press. ISBN 1-85409-130-1 – via Archive Foundation.

- Llewellyn-Jones, Malcolm, ed. (2014) [2007]. The Royal Navy and the Arctic Convoys: A Naval Staff History (2nd pbk. ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-86177-9.

- Richards, Denis; St G. Saunders, H. (1975) [1954]. Royal Air Force 1939–1945: The Fight Avails. History of the Second World War, Military Series. Vol. II (pbk. ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-771593-6. Retrieved 4 June 2018 – via Hyperwar Foundation.

- Schofield, Bernard (1964). The Russian Convoys. London: BT Batsford. OCLC 906102591 – via Archive Foundation.

- The Rise and Fall of the German Air Force (repr. Public Record Office War Histories ed.). Richmond, Surrey: Air Ministry. 2001 [1948]. ISBN 978-1-903365-30-4. Air 41/10.