1890s in Western fashion

| 1880s . 1890s in Western fashion . 1900s |

| Other topics: Anthropology . Sociology |

Fashion in the 1890s in European and European-influenced countries is characterized by long elegant lines, tall collars, and the rise of sportswear. It was an era of great dress reforms led by the invention of the drop-frame safety bicycle, which allowed women the opportunity to ride bicycles more comfortably, and therefore, created the need for appropriate clothing.[1]

Another great influence on women's fashions of this era, particularly among those considered part of the Aesthetic Movement in America, was the political and cultural climate. Because women were taking a more active role in their communities, in the political world, and in society as a whole, their dress reflected this change. The more freedom to experience life outside the home that women of the Gilded Age acquired, the more freedom of movement was experienced in fashions as well. As the emphasis on athleticism influenced a change in garments which allowed for freedom of movement, the emphasis on less rigid gender roles influenced a change in dress which allowed for more self-expression, and a more natural silhouette of women's bodies were revealed.

The 1890s brought the beginnings of a change in how fashion was presented as well. While illustrations still dominated fashion magazines, printed fashion photographs first appeared in French magazine La Mode Pratique in 1892, where they would continue be a weekly feature.[2]

Women's fashions

Fashionable women's clothing styles shed some of the extravagances of previous decades (so that skirts were neither crinolined as in the 1850s, nor protrudingly bustled in back as in the late 1860s and mid-1880s, nor tight as in the late 1870s), but corseting continued unmitigated, or even slightly increased in severity. Early 1890s dresses consisted of a tight bodice with the skirt gathered at the waist and falling more naturally over the hips and undergarments than in previous years. Puffy leg-of-mutton sleeves (also known as gigot sleeves) made a comeback, growing bigger each year until reaching their largest size around 1895.[3]

During the mid-1890s, skirts took on an A-line silhouette that was almost bell-like. The late 1890s returned to tighter sleeves often with small puffs or ruffles capping the shoulder but fitted to the wrist. Skirts took on a trumpet shape, fitting more closely over the hip and flaring just above the knee. Corsets in the 1890s helped define the hourglass figure as immortalized by artist Charles Dana Gibson. In the very late 1890s, the corset elongated, giving the women a slight S-bend silhouette that would be popular well into the Edwardian era.

Sportswear and tailored fashions

Changing attitudes about acceptable activities for women also made sportswear popular for women, with such notable examples as the bicycling dress and the tennis dress.

Unfussy, tailored clothes, adapted from the earlier theme of men's tailoring and simplicity of form, were worn for outdoor activities and traveling.[4] The shirtwaist, a costume with a bodice or waist tailored like a man's shirt with a high collar, was adopted for informal daywear and became the uniform of working women. Walking suits featured ankle-length skirts with matching jackets. The notion of "rational dress" for women's health was a widely discussed topic in 1891, which led to the development of sports dress. This included ample skirts with a belted blouse for hockey. In addition, cycling became very popular and led to the development of "cycling costumes", which were shorter skirts or "bloomers" which were Turkish trouser style outfits. By the 1890s, women bicyclists increasingly wore bloomers in public and in the company of men as well as other women. Bloomers seem to have been more commonly worn in Paris than in England or the United States and became quite popular and fashionable. In the United States, bloomers were more intended for exercise than fashion. The rise of American women's college sports in the 1890s created a need for more unencumbered movement than exercise skirts would allow. By the end of the decade, most colleges that admitted women had women's basketball teams, all outfitted in bloomers.[5] Across the nation's campuses, baggy bloomers were paired with blouses to create the first women's gym uniforms.[6]

The rainy daisy was a style of walking or sports skirt introduced during this decade, allegedly named after Daisy Miller,[7] but also named for its practicality in wet weather, as the shorter hemlines did not soak up puddles of water.[8] They were particularly useful for cycling, walking or sporting pursuits as the shorter hems were less likely to catch in the bicycle mechanisms or underfoot, and enabled freer movement.[8]

Swimwear was also developed, usually made of navy blue wool with a long tunic over full knickers.

Day dresses typical of the time period had high necks, wasp waists, puffed sleeves and bell-shaped skirts. Gowns had a squared decolletage, a wasp-waist cut and skirts with long trains.

Influence of aesthetic dress

The 1890s in both Europe and North America saw growing acceptance of artistic or aesthetic dress as mainstream fashion influenced by the philosophies of John Ruskin and William Morris.[9] This was especially seen in the adoption of the uncorseted tea gown for at-home wear. In the United States during this period, Dress, the Jenness Miller Magazine (1887–1898) [1], reported that tea gowns were being worn outside the home for the first time in fashionable summer resorts.

Before women acquired a more prominent role outside the home, before they were involved in more community, cultural and political pursuits, a more traditionally Victorian, restrained, and what was considered modest dress dominated. As Mary Blanchard writes in her article in The American History Review, "Boundaries and the Victorian Body: Aesthetic Fashion in Gilded Age America," "Little noticed, but crucial, was a shift in attitudes toward women's fashion in the 1870s and 1880s, a countercultural shift taking place under the aegis of the Aesthetic Movement. At this time, some women used their bodies and their dress as public art forms not only to defy the moral implications of domesticity but to assume cultural agency in their society at large." (Blanchard, page 22)

Hairstyles and headgear

Hairstyles at the start of the decade were simply a carry-over from the 1880s styles that included curled or frizzled bangs over the forehead as well as hair swept to the top of the head, but after 1892, hairstyles became increasingly influenced by the Gibson Girl. By the mid-1890s, hair had become looser and wavier and bangs gradually faded from high fashion. By the end of the decade, hair was often worn in a large mass with a bun at the top of the head, a style that would be predominant during the first decade of the 20th century.

Shoes

High tab front shoes with a large buckle had made a comeback in the 1870s and were again revived in the 1890s. This popular style of shoe had a few names such as "Cromwell," "Colonial," and "Molière".[10] At this time materials such as suede, leather, lace and metal were used to fashion the shoe and decorate it. Suede was new to the market in 1890 and was available in a few pale shades.

Athletic wear

The shift toward functional fashion also affected women's athletic wear. Women in Paris began wearing bloomers when bicycling as early as 1893, while in England lower bicycle frames accommodated the dresses that women continued to wear for bicycling. Long floor length dresses gradually gave way to shorter hemlines and a more casual style of athletic clothing. Similarly, bathing suits also became shorter and less covered — yet another example of the beginnings of a shift in dress toward greater freedom and functionality.[11]

Style gallery 1890–1896

-

1 – 1890–1892

-

2 - 1890-1895

-

3 – 1892

-

4 – 1892–93

-

5 – 1893

-

6 – 1894

-

7 – 1895

-

8 – 1895

-

9 – 1896

-

10 - 1896

- Praskovia Tchaokovskaia wears a high-necked afternoon dress with puffed elbow-length sleeves and a fabric belt or sash, Russia, 1890–92.

- Bathing suit, 1890-1895, nautical fashion : navy color and sailor collar and sleeves

- Day dresses of 1892 have low waists and high necklines. Sleeves have a high, gathered sleeve-head and are fitted to the lower arm. Skirts are fuller in back than front.

- Gowns of 1892–3 feature short or elbow-length full, puffed sleeves and floral trimmings.

- City or traveling suit has full upper sleeves and back fullness in the skirt.

- Walking suits of 1894 show shorter skirts and matching jackets with leg o' mutton sleeves.

- Portrait photograph of Ernesto Tornquist and his family, c. 1895.

- Punch Cartoon of 1895 shows a fashionable bicycle suit.

- Natalie Barney in 1896

- Charvet advertising in 1896

Style gallery 1897–1899

-

1 – 1897

-

2 – 1897

-

3 – 1897

-

4 – 1898

-

5 – 1898

-

6 - 1898

-

7 - 1898

-

8 - 1898

-

9 - 1898-1900

-

10 – 1899

-

11 – 1899

-

12 – 1899

- Madame Faydou wears her hair in a knot on top of her head. Her black dress and her daughter's grey dress (probably mourning attire) have fashionable leg o' mutton sleeves, 1897.

- Catherine Vlasto wears a white dress with puffed elbow-length sleeves and ribbon bows. Her hair is parted in the center and poufed casually at her temples, 1897.

- 1897 fashion plate shows an idealized form of the fashionable figure. The jacket has an asymmetrical closure and new, smaller sleeve puffs.

- Bathing costumes of 1898 have nautical details such as sailor collars.

- Dress of 1898 shows a short, wide puff at the shoulder over a long, tight sleeve.

- Charvet corsage of 1898 shows a corsage by Charvet. It is a blouse of pink cambric finely plaited, and with a white cascade frill, also of cambric, down the center.

- Shirt-waist from Charvet in 1898 shows a shirt-waist from Charvet. It has a group of tucks down either side of the front and back from the shoulders, and in addition has two deep horizontal tucks across the front. A broad box-pleat at the centre is edged with a tiny black frill, which is also carried around the basque. The sleeves are tucked in diagonal groups.

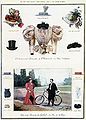

- Hats from manufacturers spring collection

- Gown (1898-1900) designed by one of the finest French couturiers during the Belle Époque, Jacques Doucet, with characteristics of the aesthetic dress movement : "simplistic in design, yet extravagant by the choice of materials used. The sheer overlayer is enhanced by the solid lamé underlayers and a sense of luxury is added by the hidden lace flounce at the hem."[12]

- 1899 fashion plate shows the narrow, gored skirt and more natural shoulder of the start of the 20th century (as well as the results of "S-bend" corseting).

- Tea Gown of 1899 shows "Watteau back" and frothy trim.

- Two women in Watteau-backed tea gowns with high sashed waists, 1899.

Cartoons

-

Cigar box art

-

Cartoon mocking sleeve designs suggesting that new styles could be modeled on cricket bats, hot air balloons, or tennis rackets.

-

1897 advertisement showing woman with unskirted garments for bicycle riding

Men's fashion

The overall silhouette of the 1890s was long, lean, and athletic. Hair was generally worn short, often with a pointed beard and generous moustache.

Coats, jackets, and trousers

By the 1890s, the sack coat (UK lounge coat) was fast replacing the frock coat for most informal and semi-formal occasions. Three-piece suits ("ditto suits") consisting of a sack coat with matching waistcoat (U.S. vest) and trousers were worn, as were matching coat and waistcoat with contrasting trousers. Contrasting waistcoats were popular, and could be made with or without collars and lapels. The usual style was single-breasted.

The blazer, a navy blue or brightly colored or striped flannel coat cut like a sack coat with patch pockets and brass buttons, was worn for sports, sailing, and other casual activities.

The Norfolk jacket remained fashionable for shooting and rugged outdoor pursuits. It was made of sturdy tweed or similar fabric and featured paired box pleats over the chest and back, with a fabric belt. Worn with matching breeches (or U.S. knickerbockers), it became the Norfolk suit, suitable for bicycling or golf with knee-length stockings and low shoes, or for hunting with sturdy boots or shoes with leather gaiters.

The cutaway morning coat was still worn for formal day occasions in Europe and major cities elsewhere.

The most formal evening wear remained a dark tail coat and trousers with a dark or light waistcoat. Evening wear was worn with a white bow tie and a shirt with a winged collar.

The less formal dinner jacket or tuxedo, which featured a shawl collar with silk or satin facings, now generally had a single button. Dinner jackets were appropriate formal wear when "dressing for dinner" at home or at a men's club. The dinner jacket was worn with a white shirt and a dark tie.

Knee-length topcoats, often with contrasting velvet or fur collars, and calf-length overcoats were worn in winter.

Shirts and neckties

Shirt collars were turned over or pressed into "wings", and became taller through the decade. Dress shirts had stiff fronts, sometimes decorated with shirt studs and buttoned up the back. Striped shirts were popular for informal occasions.

The usual necktie was a four-in-hand or an Ascot tie, made up as a neckband with wide wings attached and worn with a stickpin, but the 1890s also saw the return of the bow tie (in various proportions) for day dress.

Accessories

As earlier in the century, top hats remained a requirement for upper class formal wear; bowlers and soft felt hats in a variety of shapes were worn for more casual occasions, and flat straw boaters were worn for yachting and at the seashore.

Style gallery

-

1 – c. 1890

-

2 – c. 1890

-

3 – 1890s

-

4 – 1895

-

5 – 1896

-

6 – 1898

-

7 - 1898

- Painter John Singer Sargent in formal evening clothes, c. 1890.

- Another portrait of Sargent, in day dress: dark coat and waistcoat, dark red ascot, and tall collar, c. 1890. This picture shows the long, lean silhouette in fashion at this time.

- Oscar Wilde wears a frock coat with a pocket square, 1890s.

- Frederick Law Olmsted wears a tan topcoat over a gray suit, 1895.

- George du Maurier wears a double-breasted waistcoat with a shawl collar under his sack coat, with grey trousers. He wears square-toed shoes with spats, 1896.

- Country clothes: James Tissot wears breeches and high boots with a reddish collared waistcoat and a brown coat. Even with this casual outdoor costume, he wears a tie, 1898.

- College fashion includes a straw boater. William Beveridge at Balliol, 1898.

Children's fashion

-

Group of children, 1890

-

Girl with jump rope, 1892

-

Girls, 1896

-

Girls' fashions, 1897

-

Girls, 1897

-

A girl with a doll, 1898

-

Sigrid Juselius, 1898

Working clothes

-

Cowboys in Texas, 1891

-

Maid, 1892

-

Townswoman and fisherwoman, 1894

-

Rector and drinker, 1894

Notes

See also

References

- ^ Cunningham, Patricia; Sally Sims (1991). "The Bicycle, the Bloomer, and Dress Reform in the 1890s". Dress and Popular Culture. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State University Popular Press.

- ^ Croll, Jennifer (2014). Fashion that Changed the World. Munich: Prestel Verlag. pp. 39, 46. ISBN 978-3791347899. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Kyoto Costume Institute (2002). Fashion: A History from the 18th to the 20th Century. Taschen. p. 299. ISBN 3822812064.

- ^ Hollander, Anne (1992). "The Modernization of Fashion". Design Quarterly. No. 154 (Winter, 1992): 27–33. doi:10.2307/4091263. JSTOR 4091263.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Warner, 2006, p. 204

- ^ Warner, 2006, p. 206

- ^ Olson, Sidney (1997). Young Henry Ford : a picture history of the first forty years. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. p. 84. ISBN 9780814312247.

- ^ a b Hill, Daniel Delis (2007). As seen in Vogue : a century of American fashion in advertising (1. pbk. print. ed.). Lubbock, Tex.: Texas Tech University Press. pp. 23–25. ISBN 9780896726161.

- ^ Blanchard, Mary W. (February 1995). "Boundaries and the Victorian Body: Aesthetic Fashion in Gilded Age America". The American History Review. 1. 100 (1): 22. doi:10.2307/2167982. JSTOR 2167982.

- ^ "Evening Pumps". The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ B. Payne, "Women's Fashions of the Nineteenth Century", History of Costume: From the Ancient Egyptians to the Twentieth Century (1965)

- ^ Ball gown on Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Arnold, Janet: Patterns of Fashion 2: Englishwomen's Dresses and Their Construction C.1860–1940, Wace 1966, Macmillan 1972. Revised metric edition, Drama Books 1977. ISBN 0-89676-027-8

- Ashelford, Jane: The Art of Dress: Clothing and Society 1500–1914, Abrams, 1996. ISBN 0-8109-6317-5

- Blanchard, Mary. "The American History Review: Boundaries and the Victorian Body: Aesthetic Fashion in Gilded Age America," Oxford University Press, 1995. Vol. 100, No. 1, pp. 21-50

- Nunn, Joan: Fashion in Costume, 1200–2000, 2nd edition, A & C Black (Publishers) Ltd; Chicago: New Amsterdam Books, 2000. (Excerpts online at The Victorian Web)

- Payne, Blanche: History of Costume from the Ancient Egyptians to the 20th century, Harper & Row, 1965. No ISBN for this edition; ASIN B0006BMNFS

- Norris, Herbert, and Oswald Curtis. 19th Century Costume and Fashion, Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, INC., 1998. 227–229.

- Steele, Valerie: Paris Fashion: A Cultural History, Second Edition. New York: Berg, 1998. 175–176.

- Warner, Patricia. "When the girls came out to play: The birth of American sportswear" Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2006. ISBN 1558495495, ISBN 1558495487

External links

- Spring fashion, ca. 1890s | "From the Stacks" at New-York Historical Society

- Fashion-era

- La Couturière Parisienne

- Corsets and Crinolines

- What Victorians Wore: An Overview of Victorian Costume

- "19th Century Women's Fashion". Fashion, Jewellery & Accessories. Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- 1890s Fashions in the Staten Island Historical Society Online Collections Database

- 1890s Fashion Plates of men, women, and children's fashion from the Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries