Waterloo campaign: start of hostilities

| Waterloo campaign: start of hostilities (15 June) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Waterloo campaign | |||||||

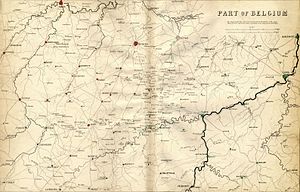

A portion of Belgium with some places marked in colour to indicate the initial deployments of the armies just before the commencement of hostilities on 15 June 1815: red Anglo-allied, green Prussian, blue French | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Napoleon | General Graf von Zieten | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Army of the North | I Corps | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 252[1]–400[2][a] | 1,200[3]-2,000[1] | ||||||

The Waterloo campaign commenced with a pre-emptive attack by the French Army of the North under the command of Napoleon Bonaparte. The first elements of the Army of the North moved from their peacetime depots on 8 June to their rendezvous point just on the French side of the Franco-Belgian border. They launched a pre-emptive attack on the two Coalition armies that were cantoned in Belgium—the Anglo-allied army under the command of the Duke of Wellington, and a Prussian army under the command of Prince Blücher.

Hostilities commenced shortly after the French advanced guard crossed the border and encountered the first Coalition outposts manned by soldiers of the Prussian I Corps (Zieten's) around 03:30 on 15 June. For the rest of the day the I Corps engaged in a fighting retreat against the overwhelming force of the French Army of the North. By midnight of 15/16 June the French had advanced north and through Charleroi and in doing so successfully crossed the river Sambre, the only significant river between the French army and Brussels.

At 19:00 on 15 June Marshal Ney, who had ridden up from Paris, met Napoleon near Charleroi, at the point where the road to Fleurus branches off from the one to Brussels. He was ordered to take command of the left wing of the Army of the North and press north up the Charleroi–Brussels road towards the Anglo-allied army and "drive back the enemy"[4] while Napoleon would advance up the Fleurus road and do the same to the Prussians. The advance up the two roads continued until darkness, but slowed during the evening as Coalition troops fell back on reinforcements. The French planned to renew their advance on 16 June, while the Anglo-allied army planned to check them at Quatre Bras, and the Prussian army at Ligny.

Prelude

On 1 March 1815 Napoleon Bonaparte landed in France after his escape from Elba, he marched on Paris. When it became clear that the troops sent to arrest him would not do so, and his arrival in the capital was imminent, Louis XVIII fled.

The representatives of the other European powers assembled at the Congress of Vienna issued a declaration outlawing Napoleon and each agreed to place armies of at least 150,000 in the field to oppose him.

The Coalition Powers agreed on a coordinated invasion of France to start on 1 July 1815. To this end it was agreed that:[5]

- Britain and Prussia would assemble their armies in Belgium (a territory recently acquired by United Kingdom of the Netherlands)

- The Russians would assemble an army and advance through Germany towards the French frontier

- The Austrians would assemble two armies and advance on the French frontiers

- The troops of Bavaria, Baden, Wurtemberg, and Hesse, would assemble their troops on the upper Rhine under the command of the Prince of Württemberg.

As soon as it became apparent that the Coalition Powers were determined to use force against him, Napoleon started to prepare for war. He had a choice of two strategies: either to assemble his forces in and around Paris and defeat the Coalition Powers as they attempted to invest the city, or to launch a pre-emptive attack and destroy each of his enemies' armies before they could combine. He chose the latter strategy and decided to attack the two Coalition armies in Belgium which were cantoned close to the borders of France.[6]

The Prussian army, commanded by Prince Blücher, was cantoned south east of Brussels with its headquarters in Namur. The Anglo-allied army, commanded by the Duke of Wellington, was cantoned south west of Brussels with its headquarters in Brussels.[6] Wellington's army included contingents from the British Army (including the KGL), Hanover (their king was also the king of Britain), Brunswick (until very recently closely associated with Hanover and hence the British), the Kingdom of the Netherlands (Dutch and Belgian troops), and Nassau (had close dynastic ties with the Netherlands and part of the territory had until very recently been ruled by the King of the Netherlands).

Napoleon's plan of campaign

Having decided to attack the Coalition forces in what is now Belgium, Napoleon had several strategies open to him and, although the Coalition commanders knew that they might well be attacked, they were uncertain as to the timing and line of advance that Napoleon would choose.

From his spies Napoleon knew how widely the Coalition forces were spread over the Low Countries. He was aware that the two armies had two distinct and divergent bases, and were commanded by two generals differing in character. His only chance of success lay in swift marches and crushing victories. He had to defeat his foes in detail, and though his aggregate force was weaker than their aggregate force, he had to be always the stronger at the point of contact.[7]

Napoleon argued in conference with his generals that he must not attack between the rivers Moselle and the Meuse, because that course would allow Wellington to join Blücher without molestation; nor must he attack between the rivers Sambre and Scheldt, because in that case Blücher would be able to effect a junction with Wellington. Nor, and for similar reasons, did he deem it prudent to descend the Meuse and attack the city of Namur.[7]

Napoleon noticed that the Coalition armies would require the longest time to concentrate on their inner flanks, and he decided to attack between the Sambre and the Meuse, to wedge himself in between them, crushing any divisions trying to obstruct his progress. Having the advantage, he planned to manoeuvre rapidly on interior lines, and defeat each army in succession before they could join forces.[7]

Napoleon had selected for the line of his main operations the direct road to Brussels, by Charleroi—the road on which Wellington's left wing, and Blücher's right wing rested. As the Prussians' front line covered Charleroi and the French territory immediately to the south of Charleroi, and the Anglo-Allies' most advanced outpost was further up the Charleroi–Brussels road at Frasnes-lez-Gosselies (about 10 miles (16 km) north of Charleroi), he planned to first overcome the Prussian army, and then attack the Anglo-allied troops before they could deploy properly.[8]

Napoleon's grand object was to prevent the two armies combining and destroy them both; to establish himself in Brussels; to arouse the dense population in Belgium (of which a vast proportion secretly adhered to his cause); to re-annex the country to the French Empire; to excite the desertion of the Belgian soldiery from the service of the Netherlands; to discourage invading armies from crossing the Rhine; perhaps also to enter into negotiations — and most important of all, to gain time to gather and train reinforcements from France.[9]

Start of operations (8–12 June)

Advance of the French Army of the North

The French IV Corps (Gérard's) left Metz on 6 June, with orders to reach Philippeville by 14 June. The Imperial Guard (commanded by Drouot) began its march from Paris on 8 June, and reached Avesnes on 13 June, as did the VI Corps (Lobau's) from Laon. The I Corps (d'Erlon's) from Lille, II Corps (Reille's) from Valenciennes, and III Corps (Vandamme's) from Mézières, likewise arrived at Maubeuge and Avesnes on 13 June. The IV Corps of Reserve Cavalry (Milhaud's) concentrated upon the Upper Sombre.[10]

Napoleon joins the army

The junction of the several corps on the same day, and almost at the same hour (with the exception of the IV, which joined the next day), displayed the usual skill of Napoleon in the combination of movements. Their leaders congratulated themselves upon these auspicious preparations, and upon finding the "Grand Army" once more assembled in "all the pomp and circumstance of glorious war":[11] the appearance of the troops, though fatigued, was all that could be desired; and their enthusiasm was at the highest on hearing that the Emperor himself, who had left Paris at 03:00 on 12 June and passed the night at Laon, had actually arrived amongst them.[12]

Upon the following day, the French Army bivouacked on three different points:[12]

- The left wing, consisting of the I Corps (d'Erlon's) and the II Corps (Reille's), and amounting to about 44,000 men, was posted on the right bank of the Sambre at Solre-sur-Sambre.

- The centre, consisting of the III Corps (Vandamme's) and the VI Corps (Lobau's), of the Imperial Guard, and of the Cavalry Reserves (I (Pajol's), II (Exelmans's), III (Kellermann's)) amounting altogether to about 60,000 men, was at Beaumont, which was made the headquarters.

- The right wing, composed of the IV Corps (Gerard's) and of a division of heavy cavalry, amounting altogether to about 16,000 men, was in front of Philippeville.

The army's bivouacs were set up with a view to conceal their fires from observation by Coalition pickets and scouts.[12][b]

The Army received through the medium of an ordre du jour (order of the day), a spirit-stirring appeal to his army from their commander and emperor (see "Proclamation on the Anniversary of the Battles of Marengo and Friedland, 14 June 1815").

13 June

French deception and limited Coalition intelligence

Napoleon had effectually concealed the movements of several corps, and their concentration on the right bank of the Sambre, by strengthening his advanced posts, and displaying an equal degree of vigilance and activity, along the whole line of the Belgian frontier.[13]

However, during the night of 13 June, the light reflected upon the sky by the French fires was noticed by observation outposts of the Prussian I Corps (Zieten's). The Prussians realised that these fires appeared to be in the direction of Walcourt and Beaumont, and also in the vicinity of Solre-sur-Sambre.[13]

Further reports from spies and deserters concurred by saying that Napoleon was expected to join the French army on that evening; that the Imperial Guard and the II Corps had arrived at Avesnes-sur-Helpe ("Avesnes") and Maubeuge; also that, at 13:00 four French battalions had crossed the river at Solre-sur-Sambre, and occupied Merbes-le-Château; that later in the night the French had pushed forward a strong detachment as far as Sars-la-Buissière; and lastly that an attack by the French would take place on 14 or 15 June.[13]

14 June

First news of the French concentration

On 14 June, the Dutch-Belgian Major-General van Merlen (who was stationed at Saint-Symphorien near Mons), and who commanded the outposts between the Saint-Symphorien and Binche which formed the extreme right of the Prussians, ascertained that French troops had moved from Maubeuge and its vicinity by Beaumont, towards Philippeville. Also that there was no longer any hostile force in his front, except a picket at Bettignies, and some National Guards in other villages. He forwarded this important information to the Prussian General Steinmetz, on his left, with whom he was in constant communication. Steinmetz despatched this information to General Zieten at Charleroi.[14]

The Prussian General Pirch II,[c] whose 2nd Brigade was posted on the left of Steinmetz, also sent word to Zieten that he had received information through his outposts that the French army had concentrated in the vicinity of Beaumont and Merbes-le-Château; that their army consisted of 150,000 men, and was commanded by General Vandamme, Prince Jerome Bonaparte, and other distinguished officers; that since the previous day all crossing of the frontier had been forbidden by the French under pain of death; and that a French patrol had been observed that day near Biercée, not far from Thuin.[15]

During the day, frequent accounts were brought to the troops of Prussian I Corps (Zieten's)—generally collaborating earlier reports—by the country people who were seeking some place of safety for their cattle. Their stories confirmed the above, and also that Napoleon, and of his brother Jerome had arrived.[15]

Zieten immediately transmitted the substance of this information to Prince Blücher and to the Duke of Wellington. This information was consistent with that which had been received from Major General Dörnberg, who had been posted in observation at Mons, and from General van Merlen (through William, Prince of Orange) who, as already mentioned, commanded the outposts between Mons and Binche.[16]

However nothing was positively known about the real point of French concentration, the probable strength of the French, or Napoleon's intended offensive movements. Because of this the two Coalition commanders refrained from altering their dispositions, and waited for better intelligence.[15]

Blücher orders the concentration of his army

Zieten's troops were kept under arms during the night, and were collected by battalions at their respective points of assembly. Later in the day Zieten's outposts reported that strong French columns, composed of all arms, were assembling in his front. This suggested an attack on the following morning, and this intelligence reached Blücher between 21:00 and 22:00 on 14 June.[17]

Orders were despatched by 23:00 for the march of the II Corps (Pirch I's) from Namur upon Sombreffe (a village on the Nivelles-Namur road close to Ligny), and of the III Corps (Thielemann's) from Ciney to Namur. Earlier that day an order had been forwarded to Bülow at Liège, ordering him to prepare his corps to Hannut in one march, and at midnight he was ordered to concentrate his troops in cantonment about Hannut.[17]

Zieten was directed to await the advance of the French in his position upon the river Sambre. In the event of him being forced to retire, he was to retreat as slowly as possible in the direction of Fleurus, to allow time for the concentration of the other three Prussian corps.[17]

Coalition uncertainty as to Napoleon's main line of attack

The vigilance which was thus exercised along both the Anglo-allied and Prussian line of outposts, obtained for Wellington and Blücher the fullest extent of information which they could reasonably have calculated on receiving respecting the dispositions of Napoleon immediately prior to an attack.[18]

Blücher and Wellington were aware that considerable masses of French troops had moved by their right, and assembled in front of Charleroi. While they were aware that French troops beyond Tournai, Mons, and Binche had moved, this could have been intended to draw the Anglo-allied army towards Charleroi. If so the French would launch a feigned attack on it, while the real attack would be by Mons.[18]

Wellington made no changes to the disposition of his forces, but Blücher immediately ordered his army to concentrate at Sombreffe (a village on the Nivelles-Namur road at the junction of a road that ran to Charleroi). They would then be able to advance through Charleroi should that be the real line of attack, but also be astride a road that would allow them to move rapidly to support Wellington, should that attack be made by the Mons road.[18]

Zieten's dispositions

Zieten's position, and his line of advanced posts, was from Bonne-Espérance (south of Binche) to Lobbes and Thuin on the Sambre through Gerpinnes and Sosoye to Dinant on the Meuse.[19][20] His right brigade (the 1st, commanded by Steinmetz), had its headquarters at Fontaine L'Evêque, and held the ground between Binche and the Sambre; his centre brigade (the 2nd commanded by Pirch II) lay along the Sambre, occupying Marchienne-au-Pont, Dampremy, Roux, Charleroi, Gilly and Châtelet; and a portion of his 3rd Brigade, commanded by Jagow) occupied Farciennes and Tamines on the Sambre, while the remainder was posted in reserve between Fleurus and the Sambre; and his left brigade (the 4th, commanded by Donnersmarck) was extended along this river nearly as far as Namur. The reserve cavalry of the I Corps had been brought more in advance, and was now cantoned in the vicinity of the Piéton,[d] having Gosselies for its point of concentration.[22]

Zieten without needing to make any alteration to his deployment, remained prepared for the expected attack on 15 June.[23]

Desertion of de Bourmont to the Coalition

While Napoleon was occupied in organising his intended order of attack, he received a despatch from Count Gérard announcing that Lieutenant General de Bourmont, and Colonels Clouet and Villoutreys, attached to the IV Corps, had deserted to the Coalition. This desertion caused Napoleon to make some alterations in his dispositions.[23]

15 June

Advance of the French army

Early in the morning of 15 June the French army commenced its march towards the Sambre in three columns, from the three bivouacs taken up during the previous night.[e] The left column advanced from Solre-sur-Sambre, by Thuin, upon Marchienne-au-Pont; the centre from Beaumont, by Ham-sur-Heure, upon Charleroi; and the right column from Philippeville, by Gerpinnes, upon Châtelet.[23]

Commencement of hostilities

At approximately 03:30 in the morning, the head of the left column came in contact with Prussian troops in front of Lobbes, firing upon, and driving in, the pickets of the 2nd Battalion of the 1st Regiment of Westphalian Landwehr, commanded by Captain von Gillhausen. This officer was aware that French troops had assembled in great force in his front the night before, and intended to attack him in the morning. He had posted his battalion carefully, so as to afford it every advantage from the hilly and intersected ground it occupied. However the French, inclined more to their right, and joined other troops advancing along the road to Thuin, which lay on his left. Shortly after they drove back an advanced cavalry vedette; and, at 04:30 commenced firing four guns on the outpost at Maladrie, about 1 mile (1.6 km) in front of Thuin.[26]

This cannonade announced the opening of the campaign by the French, and was heard by the Prussian troops forming the left wing of Steinmetz's Brigade. However the sound didn't carry well in the extremely thick and heavy air, and because of this the greater portion of the right wing of the brigade was unaware of the French advance for some time.[27]

The firing, was distinctly heard at Charleroi, and Zieten—who, by the reports which he had forwarded on 14 June to Blücher and Wellington, had fully prepared these commanders to expect an attack—lost no time in informing Blücher and Wellington that hostilities had commenced. Shortly before 05:00, he despatched Courier Jäger to their respective headquarters, Namur (Blücher) and Brussels (Wellington). He informed them that since 04:30, he had heard several cannon shots fired in his front, and at the time he was writing the fire of musketry also, but that he had not yet received any report from his outposts. To Blücher he also intimated that he should direct the whole Corps to fall back into position, and should it become absolutely necessary to concentrate at Fleurus.[27]

Zieten's report to Wellington arrived in Brussels at 09:00; that to Blücher reached Namur between 08:00 and 09:00 on 15 June. it should be pointed out that there is very serious doubt that Zieten sent a message to Wellington as early as this.[28] Muffling, the Prussian liaison officer assigned to Wellington, in his memoirs was only aware of a message that was sent between 8 am and 9 am that arrived about 5 pm with him. Wellington's own remark that he had news of Charleroi at 9 am probably meant that the news he had related to the situation at 9 am rather than the news arrived at 9 am. While it placed Wellington on the qui vive (alert), it did not induce him to adopt any particular measure, as he was writing for more definite information. But Blücher was satisfied that he had taken a wise precaution in ordereing the concentration of his several corps in the position of Sombreffe.[29]

Before 10:00 of 15 June, an order was despatched from the Prussian headquarters to the III Corps (Thielemann's) to the effect that after resting during the night at Namur, it was to continue its march upon the morning of 16 June, towards Sombreffe.[3]

At 11:30 a despatch was forwarded to Bülow, announcing the advance of the French, and requesting that the IV Corps after having rested at Hannut, should commence its march upon Gembloux no later than daybreak on 16 June.[3]

Prussian outposts driven in, the French capture Thuin and cross the Sambre

Meanwhile, the Prussian I Corps engaged the advancing enemy. The Prussian troops at Maladrie checked the advance of the French upon Thuin, and maintaining their ground for more than an hour, with the greatest bravery, but they were overpowered, and driven back upon Thuin.[30]

Thuin[30] was occupied by the 3rd Battalion of the 2nd Westphalian Landwehr, under Major von Monsterberg, who, put up a fierce resistance during which the battalion suffered an immense loss. They were forced to retire about 07:00. upon Montigny-le-Tilleul, where he found Lieutenant-Colonel Woisky, with two squadrons of the 1st West Prussian Dragoons.[30]

The French also succeeded in taking this village, but the retreat continued in good order towards Marchienne-au-Pont, under the protection of Woisky's dragoons; but before reaching Marchienne-au-Pont, the Prussians were attacked by French cavalry. The French attack was devastating for the retreating Prussians, with the infantry in particular, becoming disordered, with some cut down and many taken prisoner. So severe was the loss which the 3rd Battalion of the 2nd Westphalian Landwehr suffered in this retreat, that the mere handful of men which remained could not constitute a battalion in the proper meaning of the term.[30] It was reduced to a mere skeleton.[2] Lieutenant-Colonel von Woisky had been wounded, but continued at the head of his dragoons.[30]

Captain von Gillhausen commanded the Prussian battalion posted at Lobbes, as soon as he realised that Thuin was taken, organised his retreat. After the lapse of half an hour he drew in his pickets, and occupying the bridge over the Sambre with one company. He then fell back, and occupied the wood of Sart-de-Lobbes (near Lobbes). As the post at Hourpes had also taken by the French, he was then ordered to continue his retreat, taking a direction between Fontaine-l'Evêque and Anderlues.[31][32][f]

The Prussian post near Aulne Abbey,[g] occupied by the 3rd Battalion of the 1st Westphalian Landwehr under the temporary command of Captain Grollmann, fell into the hands of the French, between 08:00 and 09:00,[33] Hourpes which is close to the Abbey, fell to the French at about the same time. There are no action reports for the capture of these two outposts, so the Westphalians may have abandoned them shortly before Reille's advanced guard occupied them.[34]

Retreat of Zieten's troops

As soon as Greneral Steinmetz, the commander of the Prussian 1st Brigade, realised the French were advancing on his most advanced posts along the Sambre, he despatched Major Arnauld, an officer of his staff, to the Dutch-Belgian General van Merlen at Saint-Symphorien[h] to inform him of what had taken place, and that his brigade was falling back into position. On his way, Major Arnauld directed Major Engelhardt, who commanded the outposts on the right, to immediately withdraw the chain of pickets, and on arriving at Binche he spread the alarm that the French had attacked, and that the left of the brigade was warmly engaged. Until arrival of Major Arnauld, the Prussian troops in this quarter were wholly ignorant of the attack as they had not heard the sound of firing. It was now necessary that the right should retire as quickly as possible. They had further to travel than the rest of the brigade, yet they were the last to retire.[33]

Zieten ascertained around 08:00 that the whole French army appeared to be in motion, and that the direction of the advance seemed to indicate that Charleroi and its vicinity was probably the main object of the attack, sent out the fresh orders to his brigades:[35]

- The 1st was to retire by Courcelles to the position in rear of Gosselies

- The 2nd was to defend the three bridges over the Sambre, at Marchienne-au-Pont, Charleroi, and Châtelet, for a time sufficient to enable the 1st Brigade (Steinmetz's) to effect its retreat towards Gosselies, and thus to prevent its being cut off by the French, after which it was to retire behind Gilly

- The 3rd and 4th brigades, as also the reserve cavalry and artillery, were to concentrate as rapidly as possible, and to take up a position in rear of Fleurus.

The three points by which the 1st Brigade was to fall back, were Mont-Sainte-Aldegonde, for the troops on the right, Anderlues for those in the centre, and Fontaine-l'Evêque for the left. In order that they might reach these three points about the same time, Zieten ordered that those in front of Fontaine-l'Evêque should yield their ground as slowly as possible to the French attack.[36]

Having reached the line of these three points about 10:00, the brigade commenced its further retreat towards Courcelles. Its left was protected by a separate column consisting of the 1st Regiment of Westphalian Landwehr, and two companies of Silesian Rifles, led by Colonel Hoffmann, in the direction of Roux and Jumet towards Gosselies.[36]

At Marchienne-au-Pont stood the 2nd Battalion of the Prussian 6th Regiment, belonging to the 2nd Brigade of Zieten's Corps. The bridge was barricaded, and with the aid of two guns the Prussians drove the French back, after which these troops commenced their retreat upon Gilly, by Dampremy. In the latter place were three companies of the 1st Battalion of the 2nd Regiment of Westphalian Landwehr, with four guns. These also retired about the same time towards Gilly, the guns protecting the retreat by their fire from the Churchyard. The guns then moved off as rapidly as possible towards Gilly, while the Battalion marched upon Feurus. However the 4th Company which had defended the ridge of Roux until Charleroi was taken, was too late to rejoin its battalion, and attached itself to the 1st Brigade (Steinmetz's) which was retreating on its right flank.[37]

Skirmish at Couillet

Light cavalry of the I Cavalry Reserve Corps (Lieutenant General Pajol's) formed the advanced guard of the centre column of the French army. It was to have been supported by Vandamme's Corps of Infantry, but by some mistake, Vandamme had not received his orders, and at 06:00 had not left his bivouac. Napoleon, perceiving the error, led forward the Imperial Guards in immediate support of Pajol. As Pajol advanced, the Prussian outposts were hard pressed, but skirmished in good order as they retired. At Couillet, on the Sambre, about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) below Charleroi, French cavalry fell upon a company of the 3rd Battalion of the Prussian 28th Regiment, surrounded it, and forced it to surrender.[38]

French capture Charleroi

Immediately afterwards, the French gained possession of Marcinelle (in 1815 a village), which was close to Charleroi. The two were connected by a dike about 800 yards (730 m) in length, which terminated at a bridge, the head of which was palisaded. The French cavalry advanced along the dyke, but were driven back by Prussian skirmishers, who lined the hedges and ditches intersecting the opposite slope of the embankment. A part of the village was retaken by the Prussians, and an attempt made to destroy the bridge. The French attacked with increased force, and carried both the dyke and the bridge. By this means they entered Charleroi.[39]

Major Rohr, who commanded this post, abandoned the town and retreated with the 1st Battalion of the Prussian 6th Regiment, towards a prearranged position in rear of Gilly. This was done in good order, though the battalion was hotly pursued by detachments of Pajol's dragoons.[40]

11:00, the French were in full possession of Charleroi, both banks of the Sambre above the town, and Reille's Corps was effecting its passage over the river at Marchienne-au-Pont.[40]

The right column of the French Army, commanded by Gérard, having a longer distance to traverse, had not yet reached its destined point, Chatelet on the Sambre.[40]

Prussians continue to retreat

The 4th Brigade (Donnersmarck's) of I Corps (Zieten's), was also the advanced portion of the 3rd, continued their retreat towards Fleurus. General Jagow, who commanded the latter, had left two Silesian rifle companies and the Fusilier Battalion of the Prussian 7th Regiment at Farciennes and Tamines,[i] to observe French movement along the Sambre, and to protect the left flank of the position at Gilly. But when the French occupied Charleroi, and the left bank of the Sambre above that town, the situation of the 1st Brigade (Steinmetz's) became extremely critical. Zieten immediately ordered Greneral Jagow, whose brigade was in reserve, to detach Colonel Rüchel-Kleist with the 29th Regiment of Infantry to Gosselies, for the purpose of facilitating General Steinmetz's retreat.[40]

Action at Gosselies

Colonel Rüchel-Kleist found that Greneral Röder (commanding the I Corps cavalry) had posted the Prussian 6th Regiment of Uhlans (Lancers) to Gosselies. Rüchel-Kleist augmented the garrison with the 2nd Battalion of the 29th Regiment. Rüchel-Kleist placed the commander of the Uhlans, Lieutenant Colonel Lützow in command of the garrison, with orders to hold the town while he placed himself in reserve with the other two battalions.[41]

As soon as the French had assembled in sufficient force at Charleroi, Napoleon ordered Pajol to detach the 1st Brigade (General Clary's) towards Gosselies, and to advance with the remainder of the I Corps of reserve cavalry towards Gilly. General Clary, with the French 1st Hussars reached Jumet, on the left of the Brussels road, and only little more than 1 mile (1.6 km) from Gosselies, before the Prussian 1st Brigade (Steinmetz's) had crossed the Piéton. Pajol now advanced to attack Gosselies, but was met by Lieutenant Colonel Lützow and his dragoons, who defeated and repulsed him. This action gave General Steinmetz time to pass the Piéton; and as soon as he had turned the Defile of Gosselies, Colonel Rüchel-Kleist with the 29th Regiment moved off to rejoin the 3rd Brigade.[41]

The check experienced by General Clary led to his being supported by Lieutenant General Lefebvre-Desnouettes, with the light cavalry of the Guard, and the two batteries attached to this force. A regiment from the Young Guard Division (Lieutenant General Duhesme's) was advanced midway between Charleroi and Gosselies, as a reserve to Lefebvre-Desnouettes. The advanced guard of the II Corps (Reille's), which had crossed the Sambre at Marchienne-au-Pont, was also moving directly upon Gosselies, with the object of cutting off the retreat of Zieten's troops along the Brussels road, and separating the Prussians from the Anglo-allied army.[41] The French I Corps (d'Erlon's), which was considerably in the rear, received orders to follow and support Reille.[42]

Action at Heppignies

When Greneral Steinmetz approached Gosselies, he realised that the French were strong enough to completely cut him off. He quickly directed the 2nd Battalion of the 1st Westphalian Landwehr to march against the French left flank, to divert French attention to him and to check French advance. He continued his retreat towards Heppignies successfully. Protected by the 6th Lancers and the 1st Silesian Hussars, Steinmetz reached Heppignies with scarcely any loss, although he was pursued by General Girard at the head of the French 7th Division of the II Corps, as Reille continued his advance along the Brussels road with the remainder.[42]

Heppignies was already occupied by the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the Prussian 12th Regiment, and with this increase in strength Steinmetz redeployed his men. When Girard attempted to force the place, after having previously occupied Bansart, Steinmetz advanced and drove him back in the direction of Gosselies. A brisk cannonade ensued, which was maintained on the part of the Prussians, only so long as it was deemed necessary for covering their retreat upon Fleurus.[42]

Action at Gilly

Prussians stand at Gilly

In conformity with Zieten's orders, when General Pirch II was forced to abandon Charleroi he retired to Gilly, where he concentrated the 2nd Brigade. About 14:00 he took up a favourable position along a ridge in rear of a stream, his right resting upon Soleilmont Abbey with his left extending towards Châtelineau, which flank was also protected by a detachment occupying the bridge of Châtelet. Gerard's Corps had not arrived yet.[42]

Pirch II posted the Fusilier Battalion of the 6th Regiment in a small wood which lay in advance on the exterior slope of the ridge. To support them he posted four guns on the right upon a rise commanding the valley in front, two guns between this point and the Fleurus road, as also two guns on the right of the road, to impede any columns attempting to advance towards Gilly. The sharp shooters of the Fusilier Battalion of the 6th Regiment, by lining some adjacent hedges, afforded protection to the artillery.[43]

The 2nd Battalion of the 28th Regiment was stationed beyond the Fleurus road near Soleilmont Abbey, where they were concealed from the enemy. The 1st Battalion of this Regiment stood across the road leading to Lambusart; and its Fusilier Battalion was posted more to the left, towards Châtelet. The 2nd Battalion of the 2nd Westphalian Landwehr was posted in support of the battery in rear of Gilly The 1st Battalion of 2nd Westphalian Landwehr was still marching through Dampremy to Fleurus. It passed through Lodelinsart and Soleilmont, and rejoined the Brigade in rear of Gilly before the engagement had finished.[43]

The 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 6th Regiment formed the reserve. The 1st West Prussian Dragoons were posted on the slope of the ridge towards Châtelet, where they furnished vedettes and patrolled the valley of the Sambre, maintaining communication with the detachment at Farciennes, belonging to the 3rd Brigade (Jagow's).[43]

General Pirch realised that if the French succeeding in turning his right, they could advance rapidly along the Fleurns road and seriously endanger his retreat upon Lambusart To prevent this he took the precaution of having this road blocked up by an abatis in the wood through which it led.[43]

French advance on Gilly

Vandamme did not reach Charleroi until 15:00, when he received orders to pursue the Prussians along the Fleurus road in conjunction with Grouchy. Their advance was delayed as the whole of III Corps (Vandamme's) had to cross the Sambre by a single bridge, and both generals were deceived by exaggerated reports concerning the strength of the Prussians in rear of the Fleurus Woods. Grouchy went forward to reconnoitre, and returned to ask Napoleon for further instructions. Napoleon then undertook his own reconnaissance, accompanied by the four Squadrons de Service. He formed the opinion that the Prussian forces did not exceed 18–20,000 men, and gave orders for the 2nd Brigade (Pirch II's) to attack.[44]

The French generals directed their preparatory dispositions from the windmill near the Farm of Grand Drieu, and opened the engagement about 18:00 with fire from two batteries. Three columns of infantry advanced in echelon from the right, the first directing its course towards the little wood occupied by the Prussian Fusilier Battalion of the 6th Regiment; the second passing to the right of Gilly; and the third winding round the left of this village. The attack was supported by two brigades of the II Cavalry Corps (Exelmans'), namely, those of brigadier generals Burthe and Bonnemains. One was directed towards Chatelet menacing the Prussian left flank, and the other advanced along the Fleurus road.[44]

Action

The battery attached to the Prussian 2nd Brigade was replying to the superior fire from the French artillery, and the light troops were already engaged, when General Pirch received Zieten's orders to avoid an action against superior numbers, and to retire by Lambusart upon Fleurus.[45]

Realising that the French were advancing in overwhelming force, Pirch II put those orders into effect quickly, and made his dispositions accordingly. The retreat had scarcely begun when his retreating columns were vigorously assaulted by four Squadrons de Service of the Imperial Guard commanded by General Letort—a dashing, well liked and respected cavalry commander who was attached to Napoleon's staff.[46]

The Prussian infantry withstood repeated attacks by the French cavalry, aided by Lieutenant-Colonel Woisky who met the French cavalry with the 1st West Prussian Dragoons. The greater part of the Prussian force succeeded in gaining the Wood of Fleurus, but the Fusilier Battalion of the 28th Regiment (of which one company had previously been captured on the right bank of the Sambre) was broken. It had been ordered to retire into the Trichehève wood behind the hamlet of Rondchamp (or Pierrerondchamp), to the north-east of Pironchamps,[46][j] but before it could complete the movement, it was overtaken by French Imperial Guard cavalry and was vigorously assaulted, losing two thirds of its number.[47]

The Fusilier Battalion of the 6th Regiment was more fortunate. When about 500 yards (460 m) from the wood, it was attacked by French cavalry on the plain, but formed square, and repelled several charges. As the vigour of the French attacks began to slacken, the Battalion cleared its way with the bayonet through the cavalry that continued hovering round it. One of its companies extended itself along the edge of the wood, and kept the French cavalry at bay. The French cavalry suffered severely on this occasion. General Letort who led the attacks was mortally wounded[48] and died two days later on 17 June. Historians such as Philip Haythornthwaite postulate that if Letort had been present at Waterloo on 18 June, he might have affected the great French cavalry charge, and perhaps the outcome of the battle.[47]

The Brandenburg Dragoons (Watzdorf's[49]) had been detached by Zieten in support of the 2nd Brigade (Pirch II's), and opportunely reaching the field of action, they made several charges against the French cavalry, which was repulsed, ending its pursuit of the Prussian infantry.[50]

The 2nd Brigade (Pirch II's) now took up a position in front of Lambusart, which was occupied by some battalions of the 3rd Brigade (Jagow's). General Röder joined it with his remaining three regiments of cavalry and a battery of horse artillery. At this moment the French cavalry, which was formed up in position, opened a fire from three batteries of horse artillery. This brought on a cannonade, with which the affair was terminated.[50]

Prussian retreat is concluded

The Prussian 1st Brigade (Steinmetz's) having safely executed its retreat from Heppignies towards Fleurus, reached Saint-Amand about 23:00. The detachments left by the 3rd Brigade (Jagow's) at Farciennes and Tamines, had also effected their retreat without incident as did the 2nd Brigade (Pirch II's) from Lambusart, by Wanfercée-Baulet [fr], towards Fleurus, being protected by the reserve cavalry.[50]

By 03:00 I Corps (Zieten's), had established a line of advanced posts 40 miles (64 km) in length, from Dinant on the Meuse, crossing the Sambre at Thuin, and extending as far as Bonne-Espérance in advance of Binche. The main force occupied the Sambre from Thuin as far as its confluence with the Meuse, an extent of at least, 36 miles (58 km), exclusive of the numerous windings by the river between those two points.[20]

Since daybreak the Prussians of I Corps had been constantly pursued and engaged by a superior French force, headed by the elite of the French cavalry. It was not until about 23:00 that I Corps effected its concentration in position between Ligny and Saint-Amand, at a distance varying from 14 miles (23 km) to 20 miles (32 km) in rear of its original extended line of outposts; after having successfully fulfilled the arduous task imposed upon it of gaining sufficient time for the concentration, on the following day, of all the Prussian Corps, by stemming, as well as its scattered force could do, the advance of the whole of the French Army of the North.[3]

Concentration of the Prussian Army

By 15:00 of 15 June, the II Corps (Pirch I's) had taken up the position assigned to it between Onoz and Mazy in the immediate vicinity of Sombreffe, with the exception, however, of the 7th Brigade, which, having been stationed in the most remote of the quarters occupied by the II Corps, did not reach Namur until midnight. Here the latter found an order for its continuance in Namur until the arrival of the III Corps (Thielemann's); but as this had already taken place, the brigade, after a few hours' rest, resumed its march, and joined the II Corps at Sombreffe about 10:00 on 16 June.[51]

Thielemann passed the night at Namur, which he occupied with the 10th Brigade. The 9th Brigade bivouacked on the right, and the 11th on the left of Belgrade, at a village a short distance from Namur, on the road to Sombreffe. The 12th Brigade in rear of the 9th; the reserve cavalry at Flawinne, between that road and the Sambre, and the reserve artillery on the left of the road.[51]

Miscarriage of orders to Bülow

It has already been mentioned above that on 14 June, Blücher sent off a despatch to Bülow, commander of the Prussian IV Corps, directing him to arrange for his Corps to be able to reach Hannut in one march; and that at midnight of 14 June, a second despatch was forwarded, requiring him to concentrate the IV Corps at Hannut.[52]

The first of these despatches reached Bülow, at Liège, at 05:00 15 June, and he issued orders that they should be acted on as soon as the troops had breakfasted. He forwarded a report of this arrangement to headquarters. These orders to his troops had been despatched for some hours, and the consequent movements were for the most part in operation, when around 12:00, the second despatch arrived altering the destination of the Corps. Bülow considered the effect the changes would have upon the troops, namely that there would be nothing prepared for them at their new destination. As most of his commanders would not receive their new orders until evening, Bülow decided to delay the new movement until dawn of 16 June.[53]

The despatch did not require him to establish his headquarters at Hannut, but merely suggested that the latter appeared the most suitable for the purpose. Bülow was also unaware of the commencement of hostilities, which he had expected would be preceded by a declaration of war. Furthermore, he had good grounds for believing that the whole Prussian army would assemble at Hannut.[54]

Bülow made a report to Blücher's headquarters informing them of his delay in carrying out his new orders, and informing them that he would be at Hannut by 12:00 on 16 June. Captain Bklow, on Bülow's staff, who carried this despatch, and arrived at 21:00 on 15 June at Namur, where he discovered that the headquarters of the army had been transferred to Sombreffe.[54]

At 11:30 on 15 June, another despatch was forwarded to Bülow from Namur, announcing the advance of the French, and requesting that the IV Corps, after having rested at Hannut, should commence its march upon Gembloux by daybreak on 16 June at the latest. The orderly who carried it was directed to proceed to Hannut, Bülow's presumed headquarters on that day. On reaching Hannut, the orderly found the previous despatch lying in readiness for the General, and mounting a fresh horse, he went on with both despatches to Liège, where he arrived at sunrise.[54]

However the orders had now become impracticable, as Bülow's had not yet marched his Corps to Hannut. Therefore, it was impossible for the Prussian IV Corps to take part in the Battle of Ligny, which had they been able to, may have changed the outcome of the battle.[55]

Late in the evening of 15 June, after Blücher had established his headquarters at Sombreffe, Captain Below arrived with the report from Bülow, and Blücher realised that he would not be joined by the IV Corps the following day.[4]

Prussian dispositions on night 15/16 June

Of Blücher's four corps, only one, I Corps (Zieten's), had assembled in the chosen position of Ligny, on the night of 15/16 June. Of the others the:[56]

- II Corps (Pirch I's) which had arrived from Namur, was in bivouac between Onoz and Mazy, about 6 miles (9.7 km) from Ligny

- III Corps (Thielmann's), which had left its cantonments around Ciney at 07:30, passed the night at Namur, about 15 miles (24 km) from Ligny

- IV Corps (Bölow's), supposed by Blücher to be then at Hannut, was still at Liège, about 60 miles (97 km) distant from Ligny.

Prussian and French casualties

The loss of the Prussian I Corps on 15 June, amounted to 1,200 men. The Fusilier Battalions of the 28th Regiment and of the 2nd Westphalian Landwehr, reduced to mere skeletons, were united, and formed into one battalion.[3]

The French forces which attacked the Prussian I Corps sustained casualties of between 300 and 400 men[2][a]

Anglo-allied engagements

First news at Quatre Bras

The extreme left of the Duke of Wellington's army, composed of 2nd Netherlands Division (Perponcher's), rested upon the Charleroi-Brussels road. The 2nd Brigade (Colonel Goedecke's) of this division, was located thus:[58]

- 1st Battalion of the 2nd Regiment of Nassau (Büsgen's), at Houtain-le-Val;

- 2nd Battalion (Normann's), at Frasnes-lez-Gosselies and Villers-Perwin;[k]

- 3rd Battalion (Hechmann's), at Baisy-Thy [fr], Quatre Bras and Sart-Dames-Avelines;[l]

- both battalions of the 28th Regiment of Orange-Nassau (Prince Bernhard's), at Genappe.

There was also at Frasnes a Dutch horse artillery battery, under Captain Byleveld.[58]

Early on the morning of 15 June, these troops were unaware of the advance of the French army, when they heard a brisk cannonade at a distance in the direction of Charleroi. But they had not received any warning of the French advance, and they concluded that the firing was Prussian artillery practice, which they had frequently heard before, and to which they had become accustomed.[58]

However, as noon approached the cannonade became louder, and in the afternoon a wounded Prussian soldier arrived warning them of the advance of the French. A messenger was immediately sent with this information to the Regimental headquarters, from where it was also sent to Perponcher's headquarters at Nivelles.[58] Perponcher immediately ordered both brigades of his division to hurry towards their respective points of assembly - the 1st Brigade (General Bylandt's) to Nivelles, and the 2nd Brigade (Goedecke's) to Quatre Bras.[58]

In the meantime Major Normann, who commanded the 2nd Battalion of the 2nd Regiment of Nassau, drew up his battalion with the battery in position in rear of Frasnes upon the road to Quatre Bras. He also posted an observation in advance of the village.[58]

Opening of direct hostilities

About 18:00, parties of French lancers belonging to Piré's Light Cavalry Division of Reille's Corps appeared in front of Frasnes and soon drove in Major Normann's picket.[59] This officer placed a company on the south or French side of Frasnes for the purpose of delaying the entrance of the French into the village for as long as possible. Byleveld's battery took post on the north side of the village, and the remaining companies of the 2nd Battalion of the 2nd Regiment of Nassau drew up in its support. Two guns were upon the road and three on each side of it.[59]

After some time, the French lancers were reinforced, and compelled Normann's company to retire through the village and fall back upon the main body. The Prussians then opened a vigorous fire, driving back the French cavalry. The French then attempted to turn the left flank of the Prussians, but Major Normann and Captain Byleveld fell back to within a short distance of Quatre Bras. The retreat was conducted in excellent order, with the battery continuing to fire along the high road.[60]

Nassau dispositions at Quatre Bras

Before Perponcher's order reached the 2nd Brigade (Goedecke's), Prince Bernhard of Saxe Weimar, who commanded the Regiment of Orange-Nassau at Genappe, was informed by the officer of the Dutch-Belgian Maréchaussées who had been compelled to quit his post at Charleroi, that the French were advancingi. Prince Bernhard took it upon himself to move forward with his regiment from Genappe to Quatre Bras, and despatched a report of his movement to the headquarters of the Brigade at Houtain-le-Val. He subsequently sent a similar report, to Perponcher at Nivelles, by Captain Gagern of the Dutch-Belgian Staff, who was at Genappe for the purpose of collecting information.[59]

Quatre Bras was the rendezvous of the 2nd Brigade (Goedecke's), and the 3rd Battalion of the 2nd Regiment of Nassau. The 2nd Regiment was cantoned in its immediate vicinity of Quatre Bras, and without waiting for the receipt of superior orders, assembled at that point. When Prince Bernhard, on arriving at Quatre Bras with the Regiment of Orange-Nassau, he learnt of the engagement at Frasnes, and assumed command as senior officer.[61]

Realising the importance of securing the junction of the high road from Charleroi to Brussels with that from Namur to Nivelles, Prince Bernhard decided to make a firm stand at Quatre Bras. This decision was within the spirit of new orders which in the meantime had been despatched from the Dutch-Belgian headquarters at Braine-le-Comte. These new orders were the result of intelligence that the French had crossed the Sambre.[61]

General de Perponcher, who commanded the division, had also approved of the Prince's determination. Colonel Goerecke, who commanded the 2nd Brigade was at Hautain-le-Val with a broken leg, now tendered his command to Prince Bernhard, who immediately accepted it.[61][62]

The Prince pushed forward the 3rd Battalion of the 2nd Regiment of Nassau, in column, upon the high road towards Frasnes. He detached two companies of the 1st Battalion and the Volunteer Jägers to the defence of the Bossu wood, and sent the remaining companies on the high road towards Hautain le Val. He posted the remainder of the brigade at Quatre Bras, along the Namur road. Four guns of Byleveld's horse battery were posted in advance in the direction of Frasnes, two on the road to Namur and two in rear of the main body.[61]

Ney joins the Grand Army

It was 19:00 15 June, when Marshal Ney arrived, and joined Napoleon near Charleroi, at the point where the road to Fleurus branches off from the one to Brussels. After expressing his pleasure at seeing him, Napoleon gave him the command of the I and II corps. Napoleon explained that Reille was advancing with three divisions upon Gosselies, and that d'Erlon would pass the night at Marchienne-au-Pont. He also told Ney that he would have Piré's light cavalry division under his orders, and also the two regiments of chasseurs and lancers of the Guard which, he was to use only as a reserve. "To-morrow," added the Emperor, "you will be joined by the reserve corps of heavy cavalry under Kellermann. Go and drive back the Enemy".[4]

The determined resistance displayed by Prince Bernhard's forces, as well as the vigorous cannonade he maintained, and the potential flanking attack threatened by the Dutch occupying the Bossu wood, forced Piré's advanced guard to retire. He retired unmolested, and brought back exaggerated intelligence to Ney that Quatre Bras was occupied by ten battalions with artillery, and that Wellington's troops were moving to concentrate at this important point.[63]

Ney's dispositions

At 22:00 Ney's forces were thus disposed:[63]

- Piré's light Cavalry Division and Bachelu's Infantry Division occupied Frasnes-lez-Gosselies, a village situated upon the Brussels road, about 2 miles (3.2 km) on south of Quatre Bras; the two Regiments of Chasseurs and Lancers of the Guard were in reserve in rear of Frasnes.

- Reill's was with two Divisions, and the artillery attached to them, at Gosselies: these Divisions ensured the communication until the arrival of d'Erlon's Corps, which was to remain that night at Marchienne-au-Pont.

- The remaining Division of Reille's Corps (Girard's) was at Heppignies, and thus served to maintain the communication with the main column under Napoleon.

The troops were greatly fatigued by having been kept constantly on the march since 03:00; the strength of the different regiments, the names of their colonels, and even of the generals, were unknown to the Ney, as also the number of men that had been able to keep up with the heads of the columns at the end of this long march.[63]

These circumstances, combined with the information brought in from Quatre Bras, induced Ney to decline risking a night attack upon that point; and he contented himself with taking up a position in advance of Frasnes-lez-Gosselies.[63]

Having issued such orders as he deemed essential, and enjoined the most vigilant look out, Ney returned to Charleroi, where he arrived about midnight; partook of supper with Napoleon (who had just arrived from the right wing of the army), and conferred with the Emperor upon the state of affairs until two o'clock in the morning.[64]

Other French dispositions

The centre column of the French Army was thus located:[65]

- III Corps (Vandamme's) bivouacked in the Wood of Fleurus;

- Light cavalry of the I Cavalry Reserve Corps (Pajol's) at Lambusart;

- the 3rd Light Cavalry Division (Domon's), on the left, at the outlet of the Wood, and the heavy cavalry of the II Cavalry Corps (Excelmans's) between the light cavalry and III Corps;

- the Imperial Guards bivouacked between Charleroi and Gilly;

- VI Corps (Lobau's), together with heavy cavalry of the IV Cavalry Corps (Milhaud's), lay in rear of Charleroi.

The right column, consisting of IV Corps (Gérard's), had by the evening of 15 June advanced as far as the bridge at Chatelet and it bivouacked on the northern bank of the Sambre.[65]

Wellington's earliest news and orders

The first intimation which the Duke of Wellington received on 15 June, of hostilities having commenced, was conveyed in the report already alluded to, as having been forwarded by General Zieten, shortly before 05:00, and as having reached Brussels at 09:00. It was not, however, of a nature to enable Wellington to form an opinion as to any real attack being contemplated by the French in that quarter. It simply announced that the Prussian outposts in front of Charleroi were engaged. It might be the commencement of a real attack in this direction, but it might also be a diversion in favour of an attack in some other direction, such as Mons.[64]

Not long after 15:00, William, The Prince of Orange arrived in Brussels, and informed Wellington that the Prussian outposts had been attacked and forced to fall back. The Prince had ridden to the front at 05:00 in the morning, from Braine-le-Comte, and had a personal interview at Saint-Symphorien, with General van Merlen, whose troops were on the immediate right of the Prussians, who had retired. After having given van Merlen verbal orders respecting his brigade, the Prince left the outposts between 09:00 and 10:00, and travelled to Brussels to communicate to Wellington all the information he had obtained respecting the French attack upon the Prussian's advanced outposts.[66]

Wellington did not consider this sufficient evidence to take any immediate steps; but, about an hour afterwards, around 16:30, General von Müffling, the Prussian officer attached to the British headquarters, gave Wellington a communication which had been despatched from Namur by Blücher at noon, conveying the intelligence that the French had attacked the Prussian posts at Thuin and Lobbes on the Sambre, and that they appeared to be advancing in the direction of Charleroi.[67]

Wellington was fully prepared for this intelligence, though uncertain how soon it might arrive. The reports which had been made to him from the outposts, especially from those of the 1st Hussars of the King's German Legion, stationed in the vicinity of Mons and Tournai, gave sufficient indication that Napoleon was concentrating his forces. Wellington was determined to make no movement until the real line of attack should become manifest; and hence it was, that if the attack had been made even at a later period, his dispositions would have remained precisely the same.[67]

Wellington at once gave orders for the whole of his troops to assemble at the headquarters of their respective Divisions and to hold themselves in immediate readiness to march. At the same time an express was despatched to Major General Dörnberg, requiring information concerning any movement that might have been made on the part of the French in the direction of Mons.[67]

Wellington ordered the following movements:[68]

- Upon the left of the Anglo-allied army, which was nearest to the presumed point of attack — Netherlands 2nd Division (Perponcher's) and Netherlands 3rd Division (Chassé's) were to be assembled that night at Nivelles, on which point British 3rd Division (Alten's) was to march as soon as collected at Braine-le-Comte; but this movement was not to be made until the French attack upon the right of the Prussian army and the left of Wellington's had become a matter of certainty. British 1st Division (Cooke's) was to be collected that night at Enghien, and to be in readiness to move at a moment's notice.[68]

- Along the central portion of the army — British 2nd Division (Clinton's) was to be assembled that night at Ath, and to be in readiness also to move at a moment's notice. British 4th Division (Colville's) was to be collected that night at Grammont, with the exception of the troops beyond the Scheldt, which were to be moved to Audenarde.[69]

- Upon the right of Wellington's army — 1st Netherlands Division (Stedman's), and Netherlands Indies Brigade (Anthing's) were, after occupying Audenarde with 500 men, to be assembled at Zottegem, so as to be ready to march in the morning.[69]

- The cavalry were to be collected that night at Ninove, with the exception of the 2nd Hussars of the King's German Legion (Linsingen's), who were to remain on the look out between the Scheldt and the Lys; and British 3rd Cavalry Brigade (Dörnberg's), with the Cumberland Hussars (Hake's), which were to march that night upon Vilvorde, and to bivouac on the high road near to that town.[69]

- The reserve was thus disposed — British 5th Division (Picton's), the 2/81st British Regiment (Milling's), and 4th Hanoverian Brigade (Best's) — of 6th Division (Cole's), were to be in readiness to march from Brussels at a moment's notice.[69]

- 5th Hanoverian Brigade (Vincke's — of British 5th Division (Picton's) was to be collected that night at Hal, and to be in readiness at daylight on the following morning to move towards Brussels, and to halt on the road between Alost and Asse for further orders.[69]

- Brunswick Corps (Frederick, Duke of Brunswick's) was to be collected that night on the high road between Brussels and Vilvorde.[70]

- Nassau Brigade (Nassau 1st Infantry Regiment — Keuse's) was to be collected at daylight on the following morning upon the Louvain road, and to be in readiness to move at a moment's notice.[71]

- The British Reserve Artillery (Drummond's) was to be in readiness to move at daylight.[71]

Prince of Orange is informed

It was 22:00 when the first intelligence of the attack made by the French in the direction of Frasnes, was received at the Prince of Orange's headquarters, at Braine-le-Comte. It was carried by Captain Gagern, who, as previously mentioned (see above), had been despatched by Prince Bernhard of Saxe Weimar, with his report of the affair, to General Perponcher at Nivelles, and who was subsequently sent on by Perponcher, with this information to the Prince of Orange's headquarters. Lieutenant Webster, (aide-de-camp to the Prince of Orange), started soon afterwards for Brussels, with a report from the Dutch Quartermaster General, de Constant Rebecque, stating what had taken place, and detailing the measures which he had thought proper to adopt. These measures did not entirely coincide with the instructions as issued by Wellington that afternoon, because they were consequent upon the attack on Frasnes, with which Wellington at that time was unacquainted; but they were perfectly consistent with the spirit of those instructions, inasmuch as they were not adopted

until the enemy's attack upon the right of the Prussian army, and the left of the Allied army had become a matter of certainty.[71]

The French advance along the Charleroi road had already been successfully checked at Quatre Bras, and the necessity of immediately collecting at this important point, the troops ordered by Wellington "to be assembled that night at Nivelles" was too obvious to be mistaken.[72]

Wellington's second orders

A little before 22:00 on the same evening, a further communication reached Wellington from Blücher, announcing the crossing of the Sambre by the French Army of the North, headed by Napoleon in person. Intelligence from other quarters having arrived almost at the same moment and confirmed him in the opinion "that the Enemy's movement upon Charleroi was the real attack", at 22:00 Wellington issued the following orders for the march of his troops to their left:[65]

- British 3rd Division (Alten's) to continue its movement from Braine-le-Comte upon Nivelles.

- British 1st Division (Cooke's) to move from Enghien upon Braine-le-Comte.

- British 2nd and 4th Divisions (Clinton's and Colville's) to move from Ath, Grammont, and Audenarde, upon Enghien.

- The cavalry to continue its movement from Ninove upon Enghien.

Remarks on Napoleon's operations

In the opinion of the historian William Siborne the result of the proceedings on 15 June was highly favourable to Napoleon. He had completely effected the passage of the Sambre; he was operating with the main portion of his forces directly upon the preconcerted point of concentration of Blücher's army, and was already in front of the chosen position, before that concentration could be accomplished; he was also operating with another portion upon the high road to Brussels, and had come in contact with the left of Wellington's troops; he had also placed himself so far in advance upon this line that even a partial junction of the forces of the Coalition commanders was already rendered a hazardous operation, without first retreating back towards Brussels, and he thus had it in his power to bring the principal weight of his arms against the one, whilst, with the remainder of his force, he held the other at bay. This formed the grand object of his operations on the next day.[73]

William Siborne was also of the opinion that however excellent, or even perfect, this plan of operation may appear in theory, still there were other circumstances, which, if taken into consideration, put the outcome in jeopardy for the French. Napoleon's troops had been constantly under arms, marching and fighting, since 02:00 in the morning, (the hour at which they broke up from their position at Solre-sur-Sambre, Beaumont, and Philippeville, within the French frontier) so they required time for rest and refreshment. They lay widely scattered between their advanced posts and the Sambre. Ney's forces were in detached bodies from Frasnes as far as Marchienne au Pont, the halting place of d'Erlon's Corps; and although Vandamme's Corps was in the Fleurus Woods, Lobau's Corps and the Imperial Guards were halted at Charleroi, and Gisraed's Corps at Chatelet. Hence, instead of an imposing advance, with the first glimmering of the dawn on 16 June, the whole morning would necessarily be employed by the French in effecting a closer junction of their forces, and in making their preparatory dispositions for attack. This interval of time was to be invaluable to the Coalition's generals, for it allowed them time to concentrate sufficient force to hold Napoleon in check, and to frustrate his design of defeating them in detail.[74]

Given the inability of the Prussians to concentrate at Ligny before dawn on 16 June, if Napoleon had instilled more vigour in his corps commanders he could have destroyed the Prussian corps individually before they could concentrate or forced them to retreat away from Wellington's army, allowing him to turn on his other enemy. William Siborne compares the relative laxity of Napoleon's orders to Ney and his dispositions to that energetic perseverance and restless activity which characterised the most critical of his operations in former wars and concludes that to a very great degree, explain the failure of the campaign on the part of the French.[75]

Instead what happened was that Napoleon did not advance towards Fleurus until around 11:30 on 16 June, by which time the Prussian I Corps (Zieten's), II Corps (Pirch II's), and III Corps (Thielemann's) were all concentrated and in position, and he did not commence the Battle of Ligny until nearly 15:00. Ney on his side, in consequence of his operations having been rendered subordinate to those of Napoleon, dallied and did not advance with any degree of vigour against Wellington's forces until around 14:30, by which time Wellington's reserve reached Quatre Bras, from Brussels, and joined the forces already engaged in the Battle of Quatre Bras.[76]

Notes

- ^ a b Paul de Wit's figure is based on primary sources he notes two other author's casualty numbers:[57]

- 300–400 (De Mauduit, Les derniers jours etc., vol. II, p. 19)

- 500–600 (Charras, Histoire de la campagne etc., vol. I, p. 114)

- ^ French cooking fires were positions with natural obstacles (such as low hills), between the fires and direct line of sight from Coalition outposts.[12]

- ^ "Pirch II": the use of Roman numerals being used in Prussian service to distinguish officers of the same name, in this case from his brother, seven years his senior, Georg Dubislav Ludwig von Pirch "Pirch I". Because of this usage in the Prussian service, and because the two fought in the Waterloo campaign, many English language sources use the same method to distinguish the two.

- ^ A tributary of the Sambre[21]

- ^ In Charleroi, dawn on 15 June 1815 occurred at 03:47 and morning twilight at 03:02.[24] At that time, local summer time was based on solar time,[25] not as it is now on Central European Summer Time.

- ^ Siborne (1848) spells the outpost "Hoarbes", Hofschröer (2005) "Hourpes". The road out of Hourpes ("Rue d'Hourpes") joins the Lobbes-Anderlues road which if the French got there first would have cut off any Prussian troops still in Lobbes

- ^ Aulne Abby is on the north bank of Samber to the north east of Thuin — and very close to the location of the first bridge upstream from Thuin.

- ^ Saint-Symphorien is located on the road between Binche and Mons

- ^ At this time the Prussian infantry regiments generally consisted of three battalions, of which the third was the fusilier battalion.[40]

- ^ Sources which mention this action state it took place near "wood by Rondchamp" (Siborne 1848, p. 109); "the wood behind Pierrerondchamp" (Wit 2012, p. 5); "about 500 paces from the Trichehève wood" (Hofschröer 2005, p. 32). Rondchamp would appear to be a shortening of Pierrerondchamp as Plate 1 from Atlas to History of the Waterloo Campaign by William Siborne contains the location of Rondchamp and The Kaart van Farraris plan does not have an entry for Rondchamp but it does have an entry for "Pierre Rond Champ" (map 98 — Fleuru - Fleurus) in about the same location. The woods just to its east of "Pierre Rond Champ" 50°26′15″N 4°32′02″E / 50.43742°N 4.53387°E had and still have a distinctive shape. The western end is marked as "Bois du Roton" on Google Maps and some others.

- ^ Frasnes-lez-Gosselies is a village about 2.5 miles (4.0 km) south of Quatre Bras slightly to the west of the Charleroi road, while Villers-Perwin (which Siborne spells Villers-Peruin), is about 5 miles (8.0 km) south of Quatre Bras slightly to the east of the Charleroi road

- ^ Baisy-Thy (which Siborne calls Bézy) is 1.9 miles (3 km) north-north-east of Quatre Bras close to the Brussels road, and Sart-Dames-Avelines (which Siborne calls Sart-à-Mavelines) is about the same distance east of Quatre Bras just north of the Namur road — So Hechmann' Battalion was in the triangle of land just north east of Quatre Bras.

- ^ a b Hussey 2017, p. 362.

- ^ a b c Wit 2009, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e Siborne 1848, p. 111.

- ^ a b c Siborne 1848, p. 114.

- ^ Siborne 1848, pp. 50–53.

- ^ a b Hyde 1905, pp. 5–7.

- ^ a b c Hooper 1862, p. 58.

- ^ Siborne 1848, p. 88.

- ^ Siborne 1848, pp. 88–90.

- ^ Siborne 1848, p. 91.

- ^ Siborne 1848, pp. 91–92.

- ^ a b c d Siborne 1848, p. 92.

- ^ a b c Siborne 1848, p. 94.

- ^ Siborne 1848, pp. 94–95.

- ^ a b c Siborne 1848, p. 95.

- ^ Siborne 1848, pp. 95–96.

- ^ a b c Siborne 1848, p. 96.

- ^ a b c Siborne 1848, p. 97.

- ^ Hamley 1866, p. 128.

- ^ a b Siborne 1848, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Hooper 1862, p. 71.

- ^ Siborne 1848, pp. 97–98.

- ^ a b c Siborne 1848, p. 98.

- ^ Time and Date AS.

- ^ Fitchett 2006, Chapter: King-making Waterloo.

- ^ Siborne 1848, p. 98–99.

- ^ a b Siborne 1848, p. 99.

- ^ see Gareth Glover "Waterloo Myth and Reality"

- ^ Siborne 1848, pp. 99–100.

- ^ a b c d e Siborne 1848, p. 100.

- ^ Siborne 1848, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Hofschröer 2005, p. 27.

- ^ a b Siborne 1848, p. 101.

- ^ Wit 2008, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Siborne 1848, pp. 101–102.

- ^ a b Siborne 1848, p. 102.

- ^ Siborne 1848, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Siborne 1848, p. 103.

- ^ Siborne 1848, pp. 103–104.

- ^ a b c d e Siborne 1848, p. 104.

- ^ a b c Siborne 1848, p. 105.

- ^ a b c d Siborne 1848, p. 106.

- ^ a b c d Siborne 1848, p. 107.

- ^ a b Siborne 1848, p. 108.

- ^ Siborne 1848, pp. 108–109.

- ^ a b Siborne 1848, p. 109.

- ^ a b Haythornthwaite 2002, p. 27.

- ^ Siborne 1848, p. 109–110.

- ^ Millar 2004.

- ^ a b c Siborne 1848, p. 110.

- ^ a b Siborne 1848, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Siborne 1848, pp. 112.

- ^ Siborne 1848, pp. 112–113.

- ^ a b c Siborne 1848, p. 113.

- ^ Siborne 1848, p. 113–114.

- ^ Siborne 1848, p. 126.

- ^ Wit 2009, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f Siborne 1848, p. 115.

- ^ a b c Siborne 1848, p. 116.

- ^ Siborne 1848, p. 116–117.

- ^ a b c d Siborne 1848, p. 117.

- ^ Glover 2010, pp. 159–160, 238 (footnote 371).

- ^ a b c d Siborne 1848, p. 118.

- ^ a b Siborne 1848, p. 118–119.

- ^ a b c Siborne 1848, p. 123.

- ^ Siborne 1848, p. 119.

- ^ a b c Siborne 1848, p. 120.

- ^ a b Siborne 1848, p. 120–121.

- ^ a b c d e Siborne 1848, p. 121.

- ^ Siborne 1848, pp. 121–122.

- ^ a b c Siborne 1848, p. 122.

- ^ Siborne 1848, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Siborne 1848, pp. 123–124.

- ^ Siborne 1848, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Siborne 1848, p. 125.

- ^ Siborne 1848, p. 127–128.

References

- Fitchett, W. H. (2006) [1897], "Chapter: King-making Waterloo", Deeds that Won the Empire. Historic Battle Scenes, London: John Murray (Project Gutenberg)

- Glover, Gareth (2010), Waterloo Archive: German Sources, vol. 2 (illustrated ed.), Frontline Books, pp. 159–160, 233 (footnote 321), 238 (footnote 371), ISBN 9781848325418

- Hamley, Sir Edward Bruce (1866), "Example of a Force retarding the advance of a superior enemy", The operations of war explained and illustrated, Edinburgh: W. Blackwood, pp. 128–129

- Haythornthwaite, Philip J. (2002), Napoleon's Commanders, C1809-15, vol. 2 (illustrated ed.), Osprey Publishing, pp. 26–27, ISBN 9781841763453

- Hofschröer, Peter (2005), Waterloo 1815: Quatre Bras, Pen and Sword, p. 27, 32, ISBN 9781473820562

- Hooper, George (1862), Waterloo, the downfall of the first Napoleon: A History of the Campaign of 1815 (with maps and plans ed.), London: Smith, Elder and Company, p. 71

- Hussey, John (2017). Waterloo: The Campaign of 1815, Volume 1. Greenhill Books. ISBN 978-1784381981.

- Kelly, William Hyde (1905), The battle of Wavre and Grouchy's retreat : a study of an obscure part of the Waterloo campaign, London: J. Murray

- Millar, Stephen (July 2004), Prussian Army of the Lower Rhine: the Waterloo Campaign 1815, retrieved 20 July 2019

- Sun rise in Charleroi, in what is now Belgium, during June 1815, Time and Date AS, retrieved 6 November 2016

- Wit, Pierre de (21 March 2008), "15th June 1815: The 2nd corps" (PDF), The campaign of 1815: a study, Emmen, the Netherlands

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Wit, Pierre de (15 February 2009), "The Prussian and French casualties on the 15th of June" (PDF), The campaign of 1815: a study, Emmen, the Netherlands

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Wit, Pierre de (13 July 2012), "The right wing: the action at Gilly" (PDF), The campaign of 1815: a study, Emmen, the Netherlands

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Attribution

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Siborne, William (1848), The Waterloo Campaign, 1815 (4th ed.), Westminster: A. Constable

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Siborne, William (1848), The Waterloo Campaign, 1815 (4th ed.), Westminster: A. Constable

Further reading

- Siborne, William (1844), "Part of Belgium", Atlas to William Siborne's History of the Waterloo Campaign

- "Map 98 — Fleuru - Fleurus", Kabinetskaart der Oostenrijkse Nederlanden et het Prinsbisdom Luik, Kaart van Farraris, 1777