Wealth inequality in the United States

The inequality of wealth (i.e. inequality in the distribution of assets) has substantially increased in the United States in recent decades.[2] Wealth commonly includes the values of any homes, automobiles, personal valuables, businesses, savings, and investments, as well as any associated debts.[3][4]

Although different from income inequality, the two are related. Wealth is usually not used for daily expenditures or factored into household budgets, but combined with income, it represents a family's total opportunity to secure stature and a meaningful standard of living, or to pass their class status down to their children.[5] Moreover, wealth provides for both short- and long-term financial security, bestows social prestige, contributes to political power, and can be leveraged to obtain more wealth.[6] Hence, wealth provides mobility and agency—the ability to act. The accumulation of wealth enables a variety of freedoms, and removes limits on life that one might otherwise face.

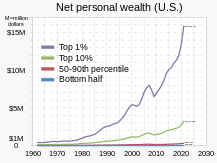

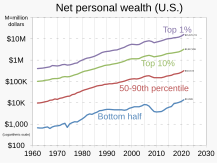

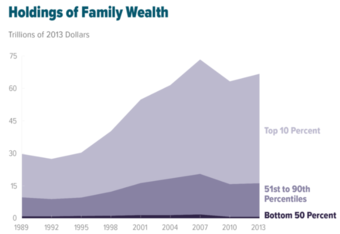

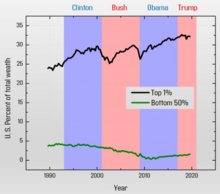

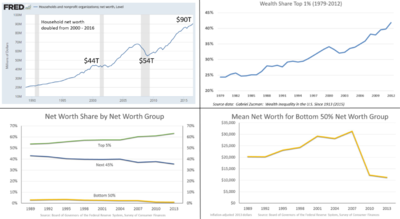

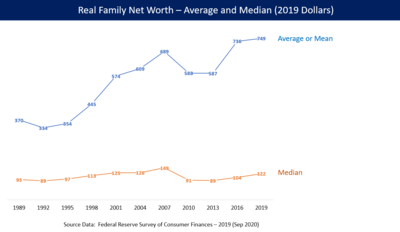

Federal Reserve data indicates that as of Q4 2021, the top 1% of households in the United States held 32.3% of the country's wealth, while the bottom 50% held 2.6%.[7] From 1989 to 2019, wealth became increasingly concentrated in the top 1% and top 10% due in large part to corporate stock ownership concentration in those segments of the population; the bottom 50% own little if any corporate stock.[8] From an international perspective, the difference in the US median and mean wealth per adult is over 600%.[9] A 2011 study found that US citizens across the political spectrum dramatically underestimate the current level of wealth inequality in the US, and would prefer a far more egalitarian distribution of wealth.[10]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the wealth held by billionaires in the U.S. increased by 70%,[11] with 2020 marking the steepest increase in billionaires' share of wealth on record.[12]

Statistics

In 2007, the top 20% of the wealthiest Americans possessed 80% of all financial assets.[14] In 2007 the richest 1% of the American population owned 35% of the country's total wealth, and the next 19% owned 51%. The top 20% of Americans owned 86% of the country's wealth and the bottom 80% of the population owned 14%. In 2011, financial inequality was greater than inequality in total wealth, with the top 1% of the population owning 43%, the next 19% of Americans owning 50%, and the bottom 80% owning 7%.[15] However, after the Great Recession, which began in 2007, the share of total wealth owned by the top 1% of the population grew from 35% to 37%, and that owned by the top 20% of Americans grew from 86% to 88%. The Great Recession also caused a drop of 36% in median household wealth, but a drop of only 11% for the top 1%, further widening the gap between the top 1% and the bottom 99%.[16][15][17]

According to PolitiFact and other sources, in 2011, the 400 wealthiest Americans had more wealth than half of all Americans combined.[18][19] Inherited wealth may help explain why many Americans who have become rich may have had a substantial head start.[20][21] In September 2012, according to the Institute for Policy Studies, over 60 percent of the Forbes richest 400 Americans grew up in substantial privilege.[22]

In 2013, wealth inequality in the U.S. was greater than in most developed countries, other than Switzerland and Denmark.[24] In the United States, the use of offshore holdings is exceptionally small compared to Europe, where much of the wealth of the top percentiles is kept in offshore holdings.[25] According to a 2014 Credit Suisse study, the ratio of wealth to household income is the highest it has been since the Great Depression.[26]

According to a paper published by the Federal Reserve in 1997, "For most households, pensions and Social Security are the most important sources of income during retirement, and the promised benefit stream constitutes a sizable fraction of household wealth" and "including pensions and Social Security in net worth makes the distribution more even."[27]

In Inequality for All—a 2013 documentary, narrated by Robert Reich, in which he argues that income inequality is the defining issue of the United States—Reich states that 95% of economic gains following the economic recovery which began in 2009 went to the top 1% of Americans (by net worth) (HNWI).[28]

A September 2017 study by the Federal Reserve reported that the top 1% owned 38.5% of the country's wealth in 2016.[29]

According to a June 2017 report by the Boston Consulting Group, around 70% of the nation's wealth will be in the hands of millionaires and billionaires by 2021.[30]

A 2019 study by economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman found that the average effective tax rate paid by the richest 400 families (0.003%) in the US was 23 percent, more than a percentage point lower than the 24.2 percent paid by the bottom half of American households.[31][32] The Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center found that the bottom 20 percent of earners pay an average 2.9 percent effective income tax rate federally, while the richest 1 percent paid an effective 29.6 percent tax rate and the top 0.01 percent paid an effective 30.6 percent tax rate.[33] In 2019, the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy found that when state and federal taxes are taken into account, however, the poorest 20 percent pay an effective 20.2 percent rate while the top 1 percent pay an effective 33.7 percent rate.[34]

Using Federal Reserve data, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth reported in August 2019 that: "Looking at the cumulative growth of wealth disaggregated by group, we see that the bottom 50 percent of wealth owners experienced no net wealth growth since 1989. At the other end of the spectrum, the top 1 percent have seen their wealth grow by almost 300 percent since 1989. Although cumulative wealth growth was relatively similar among all wealth groups through the 1990s, the top 1 percent and bottom 50 percent diverged around 2000."[35]

According to an analysis of Survey of Consumer Finances data from 2019 by the People's Policy Project, 79% of the country's wealth is owned by millionaires and billionaires.[36][37]

Also in 2019, PolitiFact reported that three people (less than the 400 reported in 2011) had more wealth than the bottom half of all Americans.[38][39][40]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the wealth held by billionaires in the U.S. increased by 70%.[11] According to the 2022 World Inequality Report, "2020 marked the steepest increase in global billionaires' share of wealth on record."[12]

As of late 2022, according to Snopes, 735 billionaires collectively possessed more wealth than the bottom half of U.S. households ($4.5 trillion and $4.1 trillion respectively). The top 1% held a total of $43.45 trillion.[41]

Late 18th century

In the late 18th century, “incomes were more equally distributed in colonial America than in any other place that can be measured,” according to Peter Lindert and Jeffrey Williamson. The richest 1 percent of households held only 8.5% of total income in the late 18th century. The Gini coefficient, which measures inequality on a scale from 0 to 1(with 1 being very high inequality) was 0.367 in New England and the Middle Atlantic, as compared to 0.57 in Europe. Some reasons for this include the ease that the average American had in buying frontier land, which was abundant at the time, and an overall scarcity of labor in non-slaveholding areas, which forced landowners to pay higher wages. There were also relatively few poor people in America at the time, since only those with at least some money could afford to come to America.[42]

19th century

Inequality grew in the 19th century; between 1774 and 1860, the Gini coefficient grew from 0.441 to 0.529. In 1860, the top 1 percent collected almost one-third of property incomes, as compared to 13.7% in 1774. There was a great deal of competition for land in the cities and non-frontier areas during this time period, with those who had already acquired land becoming richer than everyone else. The newly burgeoning financial sector also greatly rewarded the already-wealthy, as they were the only ones financially sound enough to invest.[42]

Early 20th century

Simon Kuznets, using income tax records and his research-based estimates, showed a reduction of about 10% in the movement of national income toward the top 10% of wealth-owners, a reduction from about 45–50% in 1913 to about 30–35% in 1948.[43] This period spans both The Great Depression and World War II, events with significant economic consequences. This is called the Great Compression. Franklin D. Roosevelt's establishment of social programs under the New Deal and efforts towards wealth redistribution also reduced wealth inequality.[42]

1989 to 2020

Effect of stock market gains

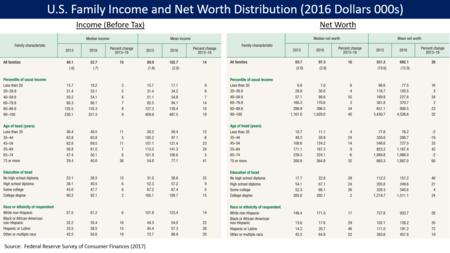

The Federal Reserve publishes information on the distribution of household assets, debt, and equity (net worth) by quarter going back to 1989. The tables below summarize the net worth data, in real terms (adjusted for inflation), for 1989 to 2022, and 2016 to 2022.[44][45] Journalist Matthew Yglesias explained in June 2019 how the ownership of stock has driven wealth inequality, as the bottom 50% has minimal stock ownership: "...[T]he bottom half of the income distribution had a huge share of its wealth tied up in real estate while owning essentially no shares of corporate stock. The top 1 percent, by contrast, wasn't just rich — it was specifically rich in terms of owning companies, both stock in publicly traded ones ("corporate equities") and shares of closely held ones ("private businesses")...So the value of those specific assets — assets that people in the bottom half of the distribution never had a chance to own in the first place — soared."[8]

The National Public Radio, also known as NPR reported, in 2017 that the bottom 50% of U.S. households (by net worth) have little stock market exposure (neither directly nor indirectly through 401k plans), writing: "That means the stock market rally can only directly benefit around half of all Americans — and substantially fewer than it would have a decade ago when nearly two-thirds of families owned stock."[46]

| Household Net Worth | Top 1% | 90th to 99th | 50th to 90th | Bottom 50% | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q3 1989 ($ trillions) | 11.51 | 18.26 | 17.72 | 1.86 | 49.35 |

| Q1 2022 ($ trillions) | 47.07 | 56.85 | 42.79 | 3.92 | 150.63 |

| Increase ($ trillions) | 35.56 | 38.59 | 25.07 | 2.06 | 101.28 |

| % Increase | 309% | 211% | 141% | 111% | 205% |

| Share of Increase (Increase/Total Increase) | 35.1% | 38.1% | 24.8% | 2.0% | 100% |

| (Intentionally left blank) | |||||

| Share of Net Worth Q3 1989 | 23.3% | 37.0% | 35.9% | 3.8% | 100% |

| Share of Net Worth Q1 2022 | 31.3% | 37.7% | 28.4% | 2.6% | 100% |

| Change in Share | +8.0% | +0.7% | -7.5% | -1.2% | 0.0% |

The table below shows changes from Q4 2016 (the end of the Obama Administration) to Q1 2022.[44]

| Household Net Worth | Top 1% | 90th to 99th | 50th to 90th | Bottom 50% | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q4 2016 ($ trillions) | 33.75 | 42.45 | 32.60 | 1.56 | 110.36 |

| Q1 2022 ($ trillions) | 47.07 | 56.85 | 42.79 | 3.92 | 150.63 |

| Increase ($ trillions) | 13.32 | 14.40 | 10.19 | 2.36 | 40.27 |

| % Increase | 39.5% | 33.9% | 31.3% | 151.3% | 36.5% |

| Share of Increase (Increase/Total Increase) | 33.1% | 35.7% | 25.3% | 5.9% | 100% |

| (Intentionally left blank) | |||||

| Share of Net Worth Q4 2016 | 30.6% | 38.5% | 29.5% | 1.4% | 100% |

| Share of Net Worth Q1 2022 | 31.3% | 37.7% | 28.4% | 2.6% | 100% |

| Change in Share | +0.7% | -0.8% | -1.1% | +1.2% | 0.0% |

Wealth and income

There is an important distinction between income and wealth. Income refers to a flow of money over time, commonly in the form of a wage or salary; wealth is a collection of assets owned, minus liabilities. In essence, income is what people receive through work, retirement, or social welfare whereas wealth is what people own.[47] While the two are related, income inequality alone is insufficient for understanding economic inequality for two reasons:

- It does not accurately reflect an individual's economic position.

- Income does not portray the severity of financial inequality in the United States.

In 1998, Dennis Gilbert asserted that the standard of living of the working and middle classes is dependent primarily upon income and wages, while the rich tend to rely on wealth, distinguishing them from the vast majority of Americans.[48]

The United States Census Bureau formally defines income as money received on a regular basis (exclusive of certain money receipts such as capital gains) before payments on personal income taxes, social security, union dues, medicare deductions, etc.[49] By this official measure, the wealthiest families may have low income, but the value of their assets may be enough money to support their lifestyle. Dividends from trusts or gains in the stock market do not fall under the aforementioned definition of income, but are commonly the primary source of capital for the ultra-wealthy. Retired people also have little income, but may have a high net worth, because of money saved over time.[50]

Additionally, income does not capture the extent of wealth inequality. Wealth is most commonly obtained over time, through the steady investing of income, and the growth of assets. The income of one year does not typically encompass the accumulation over a lifetime. Income statistics cover too narrow a time span for it to be an adequate indicator of financial inequality. For example, the Gini coefficient for wealth inequality increased from 0.80 in 1983 to 0.84 in 1989. In the same year, 1989, the Gini coefficient for income was only 0.52.[50] The Gini coefficient is an economic tool on a scale from 0 to 1 that measures the level of inequality. 1 signifies perfect inequality and 0 represents perfect equality. From this data, it is evident that in 1989 there was a discrepancy in the level of economic disparity; the extent of wealth inequality was significantly higher than income inequality. Recent research shows that many households, in particular, those headed by young parents (younger than 35), minorities, and individuals with low educational attainment, display very little accumulation. Many have no financial assets and their total net worth is also low.[51]

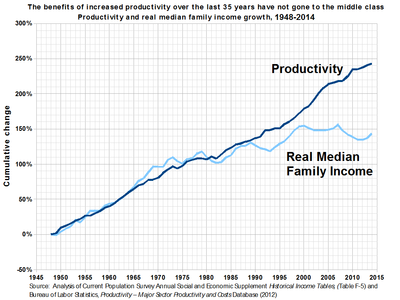

According to the Congressional Budget Office, between 1979 and 2007, incomes of the top 1% of Americans grew by an average of 275%.[52] (Note: The IRS insists that comparisons of adjusted gross income pre-1987 and post-1987 are complicated by large changes in the definition of AGI, which led to households within the top income quintile reporting more of their income on their individual income tax form's AGI, rather than reporting their business income in separate corporate tax returns, or not reporting certain non-taxable income in their AGI at all, such as municipal bond income. In addition, IRS studies consistently show that a majority of households in the top income quintile have moved to a lower quintile within one decade. There are even more changes to households in the top 1%. Without including those data here, a reader is likely to assume households in the top 1% are almost the same from year to year.[citation needed]) In 2009, people in the top 1% of taxpayers made $343,927 or more.[53][54][55] According to US economist Joseph Stiglitz the richest 1% of Americans gained 93% of the additional income created in 2010.[56][57]

A study by Emmanuel Saez and Piketty showed that the top 10 percent of earners took more than half of the country's total income in 2012, the highest level recorded since the government began collecting the relevant data a century ago.[58] People in the top one percent were three times more likely to work more than 50 hours a week, were more likely to be self-employed, and earned a fifth of their income as capital income.[59] The top one percent was composed of many professions and had an annual turnover rate of more than 25%.[60] The five most common professions were managers, physicians, administrators, lawyers, and teachers.[59]

A 2022 study in PNAS found that earnings inequality in the United States did not increase over the preceding decade, marking the first reversal of rising earnings inequality since 1980. The reversal was due to a shrinking wage gap between low-wage workers and median-wage earners, which was due to broadly rising pay in low-wage professions. At the same time, the gap between median-wage workers and top earners widened.[61]

U.S. stock market ownership distribution

| Stock owned by richest 10%.[46][62] | |

| 2016 | 84% |

| 2013 | 81% |

| 2001 | 71% |

In March 2017, NPR summarized the distribution of U.S. stock market ownership (direct and indirect through mutual funds) in the U.S., which is highly concentrated among the wealthiest families:[46]

- 52% of U.S. adults owned stock in 2016. Ownership peaked at 65% in 2007 and fell significantly due to the Great Recession.

- As of 2013, the top 1% of households owned 38% of the stock market wealth.

- As of 2013, the top 10% own 81% of the stock wealth, the next 10% (80th to 90th percentile) own 11% and the bottom 80% own 8%.

The Federal Reserve reported the median value of stock ownership by income group for 2016:

- Bottom 20% own $5,800.

- 20th-40th percentile own $10,000.

- 40th to 60th percentile own $15,500.

- 60th to 80th percentile own $31,700.

- 80th to 89th percentile own $82,000.

- Top 10% own $365,000.[64]

NPR reported that when politicians reference the stock market as a measure of economic success, that success is not relevant to nearly half of Americans. Further, more than one-third of Americans who work full-time have no access to pensions or retirement accounts such as 401(k)s that derive their value from financial assets like stocks and bonds.[46] The NYT reported that the percentage of workers covered by generous defined-benefit pension plans has declined from 62% in 1983 to 17% by 2016.[64] While some economists consider an increase in the stock market to have a "wealth effect" that increases economic growth, economists like Former Dallas Federal Reserve Bank President Richard Fisher believe those effects are limited.[46]

Causes of wealth inequality

Essentially, the wealthy possess greater financial opportunities that allow their money to make more money. Earnings from the stock market or mutual funds are reinvested to produce a larger return. Over time, the sum that is invested becomes progressively more substantial. Those who are not wealthy, however, do not have the resources to enhance their opportunities and improve their economic position. Rather, "after debt payments, poor families are constrained to spend the remaining income on items that will not produce wealth and will depreciate over time."[68] Scholar David B. Grusky notes that "62 percent of households headed by single parents are without savings or other financial assets."[69] Net indebtedness generally prevents the poor from having any opportunity to accumulate wealth and thereby better their conditions.

Economic inequality is also a result of difference in income. Factors that contribute to this gap in wages are things such as level of education, labor market demand and supply, gender differences, growth in technology, and personal abilities. The quality and level of education that a person has often corresponds to their skill level, which is justified by their income. Wages are also determined by the "market price of a skill" at that current time. Although gender inequality is a separate social issue, it plays a role in economic inequality. According to the U.S. Census Report, in America the median full-time salary for women is 77 percent of that for men. Also contributing to the wealth inequality in the U.S, both unskilled and skilled workers are being replaced by machinery. The Seven Pillars Institute for Global Finance and Ethics argues that because of this "technological advance", the income gap between workers and owners has widened.[70]

Income inequality contributes to wealth inequality. For example, economist Emmanuel Saez wrote in June 2016 that the top 1% of families captured 52% of the total real income (GDP) growth per family from 2009 to 2015. From 2009 to 2012, the top 1% captured 91% of the income gains.[71]

Nepotism perpetuates and increases wealth inequality. Wealthy families pass down their assets allowing future generations to develop even more wealth. The poor, on the other hand, are less able to leave inheritances to their children leaving the latter with little or no wealth on which to build.[68] Wealthy parents often use their economic or political power to advantage their own children, such as by providing extra funding for education, excluding poor families from the local community or schools (usually through exclusionary zoning), using social connections to provide opportunities for advancement like internships, and allowing children to take entrepreneurial risks without risking homelessness or destitution.[72]

Corresponding to financial resources, the wealthy strategically organize their money so that it will produce profit. Affluent people are more likely to allocate their money to financial assets such as stocks, bonds, and other investments which hold the possibility of capital appreciation. Those who are not wealthy are more likely to have their money in savings accounts and home ownership.[73] This difference comprises the largest reason for the continuation of wealth inequality in America: the rich are accumulating more assets while the middle and working classes are just getting by. As of 2007, the richest 1% held about 38% of all privately held wealth in the United States.[14] While the bottom 90% held 73.2% of all debt.[68] According to The New York Times, the richest 1 percent in the United States now own more wealth than the bottom 90 percent.[74]

However, other studies argue that higher average savings rate will contribute to the reduction of the share of wealth owned by the rich. The reason is that the rich in wealth are not necessarily the individuals with the highest income. Therefore, the relative wealth share of poorer quintiles of the population would increase if the savings rate of income is very large, although the absolute difference from the wealthiest will increase.[75][76][77]

The nature of tax policies in America has been suggested by economists and politicians such as Emmanuel Saez, Thomas Piketty, and Barack Obama to perpetuate economic inequality in America by steering large sums of wealth into the hands of the wealthiest Americans. The mechanism for this is that when the wealthy avoid paying taxes, wealth concentrates to their coffers and the poor go into debt.[78]

The economist Joseph Stiglitz argues that "Strong unions have helped to reduce inequality, whereas weaker unions have made it easier for CEOs, sometimes working with market forces that they have helped shape, to increase it." The long fall in unionization in the U.S. since WWII has seen a corresponding rise in the inequality of wealth and income.[79]

Some tax policies subsidize wealthy people more than poor people; critics often argue the home mortgage interest deduction should be abolished because it provides more tax relief for people in higher tax brackets and with more expensive homes, and that poorer people are more often renters and therefore less likely to be able to use this deduction at all. Regressive taxes include payroll taxes, sales taxes, and fuel taxes.

A 2022 study in the American Economic Journal found that greater economic inequality in the United States than in Europe was not because of the nature of tax and transfer systems in the United States. The study found that the U.S. redistributes a greater share of its wealth to the bottom half of the income distribution than any European country. The study found instead that Europe had less economic inequality because it had been more successful at ensuring that the bottom half of the income distribution are able to get relatively well-paying jobs.[80]

Racial disparities

The wealth gap between white and black families nearly tripled from $85,000 in 1984 to $236,500 in 2009.[81]

A Brandeis University Institute on Assets and Social Policy paper cites the number of years of homeownership, household income, unemployment, education, and inheritance as leading causes for the growth of the gap, concluding homeownership to be the most important.[81] Inheritance can directly link the disadvantaged economic position and prospects of today's blacks to the disadvantaged positions of their parents' and grandparents' generations, according to a report done by Robert B. Avery and Michael S. Rendall that pointed out "one in three white households will receive a substantial inheritance during their lifetime compared to only one in ten black households."[82] In the journal Sociological Perspectives, Lisa Keister reports that family size and structure during childhood "are related to racial differences in adult wealth accumulation trajectories, allowing whites to begin accumulating high-yield assets earlier in life."[83]

The article "America's Financial Divide" added context to racial wealth inequality, stating:

... nearly 96.1 percent of the 1.2 million households in the top one percent by income were white, a total of about 1,150,000 households. In addition, these families were found to have a median net asset worth of $8.3 million. In stark contrast, in the same piece, black households were shown as a mere 1.4 percent of the top one percent by income, that's only 16,800 homes. In addition, their median net asset worth was just $1.2 million. Using this data as an indicator only several thousand of the over 14 million African American households have more than $1.2 million in net assets ...[84]

Relying on data from Credit Suisse and Brandeis University's Institute on Assets and Social Policy, the Harvard Business Review in the article "How America's Wealthiest Black Families Invest Money" stated:[citation needed]

If you're white and have a net worth of about $356,000, that's good enough to put you in the 72nd percentile of white families. If you're black, it's good enough to catapult you into the 95th percentile." This means 28 percent of the total 83 million white homes, or over 23 million white households, have more than $356,000 in net assets. While only 700,000 of the 14 million black homes have more than $356,000 in total net worth.

According to Inequality.org, the median black family is only worth $1,700 when durables are deducted.[85] In contrast, the median white family holds $116,800 of wealth using the same accounting methods.[85] Today, using Wolff's analysis, the median African American family holds a mere 1.5 percent of median white American family wealth.[85]

A recent piece on Eurweb/Electronic Urban Report, "Black Wealth Hardly Exists, Even When You Include NBA, NFL and Rap Stars", stated this about the difference between black middle-class families and white middle-class families:

Going even further into the data, a recent study by the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS) and the Corporation For Economic Development (CFED) found that it would take 228 years for the average black family to amass the same level of wealth the average white family holds today in 2016. All while white families create even more wealth over those same two hundred years. In fact, this is a gap that will never close if America stays on its current economic path. According to the Institute on Assets and Social Policy, for each dollar of increase in average income an African American household saw from 1984 to 2009 just $0.69 in additional wealth was generated, compared with the same dollar in increased income creating an additional $5.19 in wealth for a similarly situated white household.[86]

Author Lilian Singh wrote on why the perceptions about black life created by media are misleading in the American Prospect article "Black Wealth On TV: Realities Don't Match Perceptions":

Black programming features TV shows that collectively create false perceptions of wealth for African-American families. The images displayed are in stark contrast to the economic conditions the average black family is battling each day.[87]

According to an article by the Pew Research Center, the median wealth of non-Hispanic black households fell nearly 38% from 2010 to 2013.[88] During that time, the median wealth of those households fell from $16,600 to $13,700. The median wealth of Hispanic families fell 14.3% as well, from $16,000 to $14,000. Despite the median net worth of all households in the United States decreasing with time, as of 2013, white households had a median net worth of $141,900 while black house households had a median net worth of just $11,000.[88] Hispanic households had a median net worth of just $13,700 over that time as well.[88]

In 2023, the Federal Reserve Board published median and mean family wealth statistics for 2022, based on a nationwide survey of 4,602 families.[89] The average white family's median net worth was $285,000. Hispanic families had a median net worth of $61,600, and for black families, this figure was $44,900. Although black families had the lowest median net worth of all racial groups, they experienced the greatest percent increase in net worth from 2019 to 2022, at 60 percent. For the first time, the survey calculated net worth for Asian families separately (Asian families had previously been grouped into an "other" category along with Native American, Pacific Islander, and multiracial families). Asian families had the highest median net worth, at $536,000.[89]

Effect on democracy

A 2014 study by researchers at Princeton and Northwestern concludes that government policies reflect the desires of the wealthy, and that the vast majority of American citizens have "minuscule, near-zero, statistically non-significant impact upon public policy. When a majority of citizens disagrees with economic elites and/or with organized interests, they generally lose."[90][91] When the Janet Yellen, the chair of the Federal Reserve was questioned by Senator Bernie Sanders about the study at a congressional hearing in May 2014, she responded "There's no question that we've had a trend toward growing inequality" and that this trend "can shape [and] determine the ability of different groups to participate equally in a democracy and have grave effects on social stability over time."[92]

In Capital in the Twenty-First Century, French economist Thomas Piketty argues that "extremely high levels" of wealth inequality are "incompatible with the meritocratic values and principles of social justice fundamental to modern democratic societies" and that "the risk of a drift towards oligarchy is real and gives little reason for optimism about where the United States is headed."[93]

Proposals to reduce wealth inequality

Estate tax

There is a political debate over the estate tax in the United States, which reduces inequality by taxing the estate of large quantities of wealth. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 doubled the exemption of estates by increasing the exemption from $5.49 million in 2017 to $11.18 million in 2018.[95] This increase in estate exemption was estimated to affect about 3,200 estates in 2018.[96]

A 2021 investigation using leaked IRS documents found more than half of the richest 100 Americans use grantor retained annuity trusts to avoid paying estate taxes when they die.[97]

As of 2022 individual estates under $12.06 million, and $24.12 million for married couples, are exempt from federal tax. Estates with values beyond $12.06 million are taxed on a sliding scale from 18% to 40%. The lowest bracket of 18% affects estates from $12.06 to $12.07 million and quickly increases to 40% affecting estates $13.06 million and above.[98] The doubled exemption from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 is scheduled to expire in 2025, reducing the estate exemption to approximately $6.2 million. In addition, the maximum gift tax is scheduled to increase from 40% to 45% in 2026.[99]

On top of the federal estate tax, 17 states have an estate or inheritance tax.[100]

Increased tax

In President Joe Biden's proposed budget for 2023 there are two proposed tax changes for households with wealth above $100 million.[101] First, is a new "minimum tax" at death for unrealized capital gains above $1 million. Second is to realized capital gains as ordinary income; which is expected to effectively raise the percent of capital taxed from 23.8% to 43.4%. Combined it is estimated that these tax changes will place these households at an effective tax rate of 61.1%, which is nearly double the effective tax rate in 2022.

Taxation of wealth

Senator Bernie Sanders pitched the idea of a wealth tax in the US in 2014.[102] Later, Senator Elizabeth Warren proposed an annual tax on wealth in January 2019, specifically a 2% tax for wealth over $50 million and another 1% surcharge on wealth over $1 billion. Wealth is defined as including all asset classes, including financial assets and real estate. In 2021, officials in the state of Washington considered proposals to tax wealthy residents within the state.[103]

Warren's plan received both praise and criticism. Economist Paul Krugman wrote in January 2019 that polls indicate the idea of taxing the rich more is very popular.Two billionaires, Michael Bloomberg and Howard Schultz, criticized the proposal as "unconstitutional" and "ridiculous," respectively. [104] Economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman analyzed the Warren's proposal and estimated that about 75,000 households (less than 0.1%) would pay the tax. The tax was expected to raise around $2.75 trillion over 10 years, roughly 1% GDP on average per year. This was expected to raise the total tax burden for those subject to the wealth tax from 3.2% relative to their wealth under current law to about 4.3% on average, versus the 7.2% for the bottom 99% families.[105] For scale, the federal budget deficit in 2018 was 3.9% GDP and was expected to rise towards 5% GDP over the next decade.[106] An analysis by the think tank Tax Foundation found that Warren's proposal would reduce long-term GDP by 0.37% and raise $2.2 trillion over a period of ten years, after factoring in macroeconomic feedback effects. It expected the tax to "face serious administrative and compliance challenges due to valuation difficulties and tax evasion and avoidance issues." It also expected foreign investors to replace American billionaires as the owners of capital.[107]

Limiting stock buybacks

Senators Charles Schumer and Bernie Sanders advocated limiting stock buybacks to reduce income and wealth inequality in January 2019.[108]

See also

- Affluence in the United States

- Distribution of wealth in Europe

- Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission

- Criticism of credit scoring systems in the United States

- Donor Class

- Income inequality in the United States

- Monetary policy

- Net worth

- Occupy movement

- Occupy Wall Street

- Oligarchy

- Panama Papers

- Paradise Papers

- Pareto principle

- Plutocracy

- Power elite

- Redistribution of wealth

- Tax policy and economic inequality in the United States

- The Divide: American Injustice in the Age of the Wealth Gap

- Wealth concentration

- Wealth in the United States

- We are the 99%

- American upper class

- List of Americans by net worth

References

- ^ "Trends in Family Wealth, 1989 to 2013". Congressional Budget Office. August 18, 2016. Retrieved November 29, 2016.

- ^ Smith, Matthew; Zidar, Owen; Zwick, Eric (2022). "Top Wealth in America: New Estimates under Heterogeneous Returns". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 138: 515–573. doi:10.1093/qje/qjac033. ISSN 0033-5533.

- ^ Hurst, Charles E. (2007), Social Inequality: Forms, Causes, and Consequences, Pearson Education, Inc., p. 31, ISBN 978-0-205-69829-5

- ^ Rugaber, Christopher S.; Boak, Josh (January 27, 2014). "Wealth gap: A guide to what it is, why it matters". AP News. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ Grusky, David B. Social Stratification: Class, Race, and Gender in Sociological Perspective, p. 637. Westview Press, 2001 ISBN 0-8133-6654-2

- ^ Keister, p. 64

- ^ "The Fed - Table: Distribution of Household Wealth in the U.S. since 1989". www.federalreserve.gov. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- ^ a b "New Federal Reserve data shows how the rich have gotten richer". Vox. June 13, 2019. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Anthony Shorrocks; Jim Davies; Rodrigo Lluberas (October 2018). "Global Wealth Report". Credit Suisse. October 10, 2018 article: Global Wealth Report 2018: US and China in the lead. Report[permanent dead link]. Databook[permanent dead link]. Downloadable data sheets. See Table 3.1 (page 114) of databook for mean and median wealth by country. See page 106 (end of Table 2.4) for total wealth of continents.

- ^ Norton, M.I.; Ariely, D. (2011). "Building a Better America – One Wealth Quintile at a Time" (PDF). Perspectives on Psychological Science. 6 (1): 9–12. doi:10.1177/1745691610393524. PMID 26162108. S2CID 2013655. (video)

- ^ a b Picchi, Aimee (December 7, 2021). "The new Gilded Age: 2,750 people have more wealth than half the planet". CBS News. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ^ a b "World Inequality Report 2022". October 9, 2021. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ^ a b "Evolution of wealth indicators, USA, 1913-2019". WID.world. World Inequality Database. 2022. Archived from the original on July 5, 2023. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ a b Hurst, p. 34

- ^ a b Occupy Wall Street And The Rhetoric of Equality Forbes November 1, 2011, by Deborah L. Jacobs

- ^ Recent Trends in Household Wealth in the United States: Rising Debt and the Middle-Class Squeeze—an Update to 2007 by Edward N. Wolff, Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, March 2010

- ^ Wealth, Income, and Power by G. William Domhoff of the UC-Santa Barbara Sociology Department

- ^ Kertscher, Tom; Borowski, Greg (March 10, 2011). "The Truth-O-Meter Says: True – Michael Moore says 400 Americans have more wealth than half of all Americans combined". PolitiFact. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- ^ Pepitone, Julianne (September 22, 2010). "Forbes 400: The super-rich get richer". CNN. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- ^ Bruenig, Matt (March 24, 2014). "You call this a meritocracy? How rich inheritance is poisoning the American economy". Salon. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

- ^ "Inequality – Inherited wealth". The Economist. March 18, 2014. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

- ^ Pizzigati, Sam (September 24, 2012). "The 'Self-Made' Hallucination of America's Rich". Institute for Policy Studies. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

- ^ "Household wealth inequality statistics from the Federal Reserve". Federal Reserve. March 18, 2020.

- ^ Weissmann, Jordan (March 11, 2013). "Yes, U.S. Wealth Inequality Is Terrible by Global Standards". The Atlantic. Retrieved March 16, 2013.

- ^ Peter Baldwin (2009). The narcissism of minor differences: how America and Europe are alike. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539120-6

- ^ Mark Gongloff (October 14, 2014). Key Inequality Measure The Highest Since The Great Depression. The Huffington Post. Retrieved October 14, 2014.

- ^ Pensions, Social Security, and the Distribution of Wealth by Arthur B. Kennickell and Annika E. Sundén of Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

- ^ Svaldi, Aldo (January 11, 2014). "Robert Reich: Income inequality the defining issue for U.S." The Denver Post. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ^ Bruenig, Matt (October 1, 2017). "Wealth Inequality Is Higher Than Ever". Jacobin. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ^ Steverman, Ben (June 16, 2017). "The U.S. Is Where the Rich Are the Richest". Bloomberg. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

Now, those policies and their progeny have helped put 63 percent of America's private wealth in the hands of U.S. millionaires and billionaires, BCG said. By 2021, their share of the nation's wealth will rise to an estimated 70 percent.

- ^ Rogers, Taylor Nicole (October 9, 2019). "American billionaires paid less in taxes in 2018 than the working class, analysis shows — and it's another sign that one of the biggest problems in the US is only getting worse". Business Insider. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

- ^ Ingraham, Christopher (October 8, 2019). "For the first time in history, U.S. billionaires paid a lower tax rate than the working class last year". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

- ^ "Are federal taxes progressive?". Tax Policy Center. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

- ^ Wamhoff, Steve., Gardner, Matthew (April 2019). "Who Pays Taxes in America in 2019?" (PDF). Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Federal Reserve's new distributional financial accounts provide telling data on growing U.S. wealth and income inequality". equitablegrowth.org. August 22, 2019. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ Bruenig, Matt (September 28, 2020). "Millionaires and Billionaires Own 79% of All Household Wealth". People's Policy Project. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- ^ Krystal and Saagar: NEW Data Shows Millionaires, Billionaires Own 79% Of America's Wealth Rising on YouTube, September 29, 2020.

- ^ Kertscher, Tom (July 3, 2019). "The wealthiest three families now own more wealth than the bottom half of the country. - TRUE". PolitiFact. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

- ^ Kertscher, Tom (March 10, 2011). "Just 400 Americans -- 400 -- have more wealth than half of all Americans combined. - TRUE". PolitiFact. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

- ^ Bogdan, Dennis (April 26, 2013). "Comment - USA: More Valuable Than Money?". The New York Times. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

- ^ Jayshi, Damakant (April 13, 2023). "Do 728 Billionaires Hold More Wealth Than Half of American Households?". Snopes. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- ^ a b c Semuels, Alana (April 25, 2016). "The Founding Fathers Weren't Concerned With Inequality". The Atlantic. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- ^ "He noted a sharp reduction in income inequality in the United States between 1913 and 1948. More specifically, at the beginning of this period, the upper decile of the income distribution (that is, the top 10 percent of US earners) claimed 45–50 percent of annual national income. By the late 1940s, the share of the top decile had decreased to roughly 30–35 percent of national income." Piketty, Thomas. Capital in the Twenty-First Century (Kindle Locations 298–300). Harvard University Press. Kindle Edition.

- ^ a b "Total Net Worth". fred.stlouisfed.org. October 10, 2020. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Distributional National Accounts". federalreserve.gov. February 16, 2020. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e While Trump Touts Stock Market, Many Americans Are Left Out of the Conversation. By Danielle Kurtzleben, March 1, 2017. NPR.

- ^ Grusky, page 637

- ^ Gilbert, D. (1998). The American Class Structure: In an Age of the Growing Inequality. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau, Housing and Household Economic Statistics Division; Income Overview". December 20, 2005. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- ^ a b Keister, p. 65

- ^ "Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Savings of Young Parents" (PDF). December 2000. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- ^ It's the Inequality, Stupid By Dave Gilson and Carolyn Perot in Mother Jones, March/April 2011 Issue

- ^ Who are the 1 percent?, CNNMoney.com, October 29, 2011

- ^ "Tax Data Show Richest 1 Percent Took a Hit in 2008, But Income Remained Highly Concentrated at the Top." Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Accessed October 2011.

- ^ Top Earners Doubled Share of Nation's Income, Study Finds The New York Times By Robert Pear, October 25, 2011

- ^ An ordinary Joe, The Economist, June 23, 2012,

- ^ The Price of Inequality: How Today's Divided Society Endangers Our Future, Stiglitz, J.E.,(2012) W.W. Norton & Company, ISBN 978-0393088694

- ^ Lowrey, Annie (September 10, 2013). "The Rich Get Richer Through the Recovery".

- ^ a b The Top 1 Percent - What Jobs Do They Have?. The New York Times January 14, 2012,

- ^ Divided We Stand: Why Inequality Keeps Rising. OECD (2011)

- ^ Aeppli, Clem; Wilmers, Nathan (2022). "Rapid wage growth at the bottom has offset rising US inequality". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (42): e2204305119. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11904305A. doi:10.1073/pnas.2204305119. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 9586320. PMID 36191177.

- ^ The Richest 10% of Americans Now Own 84% of All Stocks. By Rob Wile, December 19, 2017. Money.com.

- ^ Federal Reserve Bulletin. September 2017, Vol. 103, No. 3. See PDF: Changes in U.S. Family Finances from 2013 to 2016: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances. Table 1 (on the left) is taken from page 4 of the PDF. Table 2 (on the right) is taken from page 13. See: Survey of Consumer Finances and more data.

- ^ a b Rattner, Steven (January 22, 2018). "Opinion - The Market Isn't Bullish for Everyone". The New York Times. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ "Productivity growth closely matched that of median family income until the late 1970s when median American family income stagnated while productivity continued to climb. Chart comparing productivity growth and real median family income growth in the United States from 1947–2009. Source: EPI Authors' analysis of Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement Historical Income Tables, (Table F–5) and Bureau of Labor Statistics Productivity – Major Sector Productivity and Costs Database (2012)". Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- ^ "Global wage growth stagnates, lags behind pre-crisis rates, ILO, December 5, 2014". December 5, 2014. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- ^ "Federal Reserve-Survey of Consumer Finances 2017". Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- ^ a b c Hurst, p. 36

- ^ Grusky, p. 640

- ^ Leung, May (January 22, 2015). "The Causes of Economic Inequality". Seven Pillars Institute. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- ^ "Emmanuel Saez-Striking it richer: The evolution of top incomes in the U.S." (PDF). June 30, 2016. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- ^ "Redefining "Rich": Not Just The 1%". KERA-FM. July 19, 2017. (audio interview with Richard V. Reeves)

- ^ Hurst, pp. 34–35

- ^ Kristof, Nicholas (July 22, 2014). "An Idiot's Guide to Inequality". The New York Times. Retrieved July 22, 2014.

- ^ Berman, Y; Shapira, Y; Ben-Jacob, E (2015). "Modeling the Origin and Possible Control of the Wealth Inequality Surge". PLOS ONE. 10 (6): e0130181. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1030181B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0130181. PMC 4479378. PMID 26107388.

- ^ Zyga L, Model shows how surge in wealth inequality may be reversed, http://phys.org/news/2015-07-surge-wealth-inequality-reversed.html, 2015

- ^ Berman Y, Ben-Jacob E, Shapira Y (2016) The Dynamics of Wealth Inequality and the Effect of Income Distribution. PLoS ONE 11(4): e0154196, http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0154196

- ^ Berman, Y; Peters, O; Adamou, A (2016). "Far from equilibrium: Wealth reallocation in the United States". arXiv:1605.05631 [q-fin.EC].

- ^ Stiglitz, Joseph E. (June 4, 2012). The Price of Inequality: How Today's Divided Society Endangers Our Future (Kindle Locations 1148–1149). Norton. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Blanchet, Thomas; Chancel, Lucas; Gethin, Amory (2022). "Why Is Europe More Equal than the United States?". American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 14 (4): 480–518. doi:10.1257/app.20200703. ISSN 1945-7782. S2CID 222262219.

- ^ a b Thomas Shapiro; Tatjana Meschede; Sam Osoro (February 2013). "The Roots of the Widening Racial Wealth Gap: Explaining the Black-White Economic Divide" (PDF). Research and Policy Brief. Brandeis University Institute on Assets and Social Policy. Retrieved March 16, 2013.

- ^ Avery, Robert B.; Rendall, Michael S. (2002), Lifetime Inheritances of Three Generations of Whites and Blacks, vol. 107, The University of Chicago Press

- ^ Keister, Lisa A. (2004). "Race, Family Structure, and Wealth: The Effect of Childhood Family on Adult Asset Ownership" (PDF). Sociological Perspectives. 47 (2): 161–87. doi:10.1525/sop.2004.47.2.161. S2CID 11945433.

- ^ Moore, Antonio (April 13, 2015). "America's Financial Divide: The Racial Breakdown of U.S. Wealth in Black and White". HuffPost.

- ^ a b c "Our Real Racial Wealth Gap Story". Inequality.org.

- ^ "Opinion: Black Wealth Hardly Exists, Even When You Include NBA, NFL and Rap Stars". EURweb. October 12, 2016.

- ^ Singh, Lillian D. (September 26, 2014). "Black Wealth On TV: Realities Don't Match Perceptions". The American Prospect.

- ^ a b c "Wealth inequality has widened along racial, ethnic lines since end of Great Recession" (PDF).

- ^ a b "2022 Survey of Consumer Finances". Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 2023.

- ^ Martin Gilens & Benjamin I. Page (2014). "Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens" (PDF). Perspectives on Politics. 12 (3): 564–581. doi:10.1017/S1537592714001595. S2CID 8472579.

- ^ "'Corruption is Legal in America' by RepresentUs". YouTube. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021.

- ^ John Nichols (May 7, 2014). Bernie Sanders Asks Fed Chair Whether the US Is an Oligarchy. The Nation. Retrieved May 8, 2014.

- ^ Piketty, Thomas (2014). Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Belknap Press. ISBN 067443000X pp. 26, 514

- ^ "FRED Chart - Wealth inequality by wealth group 1989-Present". fred.stlouisfed.org. March 9, 2020.

- ^ "Estate Tax". IRS. IRS. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ Heather Long, Nov. 5 2017, The Washington Post "3,200 wealthy individuals wouldn't pay estate tax next year under GOP plan" Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ Jeff Ernsthausen; James Bandler; Justin Elliott; Patricia Callahan (September 26, 2021). "More Than Half of America's 100 Richest People Exploit Special Trusts to Avoid Estate Taxes". ProPublica.

- ^ Jim Probasco. "Estate Tax Exemption 2022". Investopedia. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ "Federal Estate and Gift Tax Exemption to Sunset in 2025: Are You Ready?". AdvicePeriod. March 23, 2022. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ "17 States With Estate or Inheritance Taxes Even if you escape the federal estate tax, these states may hit you". AARP. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ Garrett Watson; Scott A. Hodge (April 12, 2022). "President Biden's 61 Percent Tax on Wealth". Tax Foundation. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ "Sanders Proposes Wealth Tax; Piketty, Reich Applaud-September 6, 2014".

- ^ Mahoney, Laura (March 4, 2021). "Mega-Rich and Plans to Tax Them Abound in Washington State". Bloomberg Tax.

- ^ Krugman, Paul (January 28, 2019). "Opinion - Elizabeth Warren Does Teddy Roosevelt". The New York Times.

- ^ "Saez & Zucman-Scoring of the Warren Wealth Tax Proposal-January 18, 2019" (PDF).

- ^ "The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2019 to 2029 - Congressional Budget Office". www.cbo.gov. January 28, 2019.

- ^ "Analysis of Sen. Warren and Sen. Sanders' Wealth Tax Plans". Tax Foundation. January 28, 2020. Retrieved August 21, 2023.

- ^ Schumer, Chuck; Sanders, Bernie (February 3, 2019). "Opinion - Schumer and Sanders: Limit Corporate Stock Buybacks". The New York Times.

Further reading

- Alexandra Thornton and Galen Hendricks, Ending Special Tax Treatment for the Very Wealthy, Center for American Progress, June 4, 2019. Ending Special Tax Treatment for the Very Wealthy The report summarizes the problem (gross inequality) and its cause ("special tax treatment for the [extremely rich]"), and specific "ways to rebalance the tax code and put the economy on a better track."

- Moritz Kuhn, Moritz Schularick, and Ulrike I. Steins. 2020. "Income and Wealth Inequality in America, 1949–2016." Journal of Political Economy.

- Thomas M. Shapiro (2017). Toxic Inequality: How America's Wealth Gap Destroys Mobility, Deepens the Racial Divide, and Threatens Our Future. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465046935.