Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope | |

|---|---|

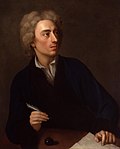

Portrait by Michael Dahl, c. 1727 | |

| Born | 21 May 1688 O.S. London, England |

| Died | 30 May 1744 (aged 56) Twickenham, Middlesex, England |

| Resting place | St Mary's Church, Twickenham, Middlesex, England |

| Occupation | Poet, writer, translator |

| Genre | Poetry, satire, translation |

| Literary movement | Classicism, Augustan literature |

| Notable works | The Dunciad, The Rape of the Lock, An Essay on Criticism, his translation of Homer |

| Signature | |

| |

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 O.S.[1] – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature,[2] Pope is best known for his satirical and discursive poetry including The Rape of the Lock, The Dunciad, and An Essay on Criticism, and for his translations of Homer.

Pope is often quoted in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, some of his verses having entered common parlance (e.g. "damning with faint praise" or "to err is human; to forgive, divine").

Life

Alexander Pope was born in London on 21 May 1688 during the year of the Glorious Revolution. His father (Alexander Pope, 1646–1717) was a successful linen merchant in the Strand, London. His mother, Edith (née Turner, 1643–1733), was the daughter of William Turner, Esquire, of York. Both parents were Catholics.[3] His mother's sister, Christiana, was the wife of famous miniature painter Samuel Cooper. Pope's education was affected by the recently enacted Test Acts, a series of English penal laws that upheld the status of the established Church of England, banning Catholics from teaching, attending a university, voting, and holding public office on penalty of perpetual imprisonment. Pope was taught to read by his aunt and attended Twyford School circa 1698.[3] He also attended two Roman Catholic schools in London.[3] Such schools, though still illegal, were tolerated in some areas.[4]

In 1700, his family moved to a small estate at Popeswood, in Binfield, Berkshire, close to the royal Windsor Forest.[3] This was due to strong anti-Catholic sentiment and a statute preventing "Papists" from living within 10 miles (16 km) of London or Westminster.[5] Pope would later describe the countryside around the house in his poem Windsor Forest.[6] Pope's formal education ended at this time, and from then on, he mostly educated himself by reading the works of classical writers such as the satirists Horace and Juvenal, the epic poets Homer and Virgil, as well as English authors such as Geoffrey Chaucer, William Shakespeare and John Dryden.[3] He studied many languages, reading works by French, Italian, Latin, and Greek poets. After five years of study, Pope came into contact with figures from London literary society such as William Congreve, Samuel Garth and William Trumbull.[3][4]

At Binfield he made many important friends. One of them, John Caryll (the future dedicatee of The Rape of the Lock), was twenty years older than the poet and had made many acquaintances in the London literary world. He introduced the young Pope to the ageing playwright William Wycherley and to William Walsh, a minor poet, who helped Pope revise his first major work, The Pastorals. There, he met the Blount sisters, Teresa and Martha (Patty), in 1707. He remained close friends with Patty until his death, but his friendship with Teresa ended in 1722.[7]

From the age of 12 he suffered numerous health problems, including Pott disease, a form of tuberculosis that affects the spine, which deformed his body and stunted his growth, leaving him with a severe hunchback. His tuberculosis infection caused other health problems including respiratory difficulties, high fevers, inflamed eyes and abdominal pain.[3] He grew to a height of only 4 feet 6 inches (1.37 metres). Pope was already removed from society as a Catholic, and his poor health alienated him further. Although he never married, he had many female friends to whom he wrote witty letters, including Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. It has been alleged that his lifelong friend Martha Blount was his lover.[4][8][9][10] His friend William Cheselden said, according to Joseph Spence, "I could give a more particular account of Mr. Pope's health than perhaps any man. Cibber's slander (of carnosity) is false. He had been gay [happy], but left that way of life upon his acquaintance with Mrs. B."[11]

In May 1709, Pope's Pastorals was published in the sixth part of bookseller Jacob Tonson's Poetical Miscellanies. This earned Pope instant fame and was followed by An Essay on Criticism, published in May 1711, which was equally well received.

Around 1711, Pope made friends with Tory writers Jonathan Swift, Thomas Parnell and John Arbuthnot, who together formed the satirical Scriblerus Club. Its aim was to satirise ignorance and pedantry through the fictional scholar Martinus Scriblerus. He also made friends with Whig writers Joseph Addison and Richard Steele. In March 1713, Windsor Forest[6] was published to great acclaim.[4]

During Pope's friendship with Joseph Addison, he contributed to Addison's play Cato, as well as writing for The Guardian and The Spectator. Around this time, he began the work of translating the Iliad, which was a painstaking process – publication began in 1715 and did not end until 1720.[4]

In 1714 the political situation worsened with the death of Queen Anne and the disputed succession between the Hanoverians and the Jacobites, leading to the Jacobite rising of 1715. Though Pope, as a Catholic, might have been expected to have supported the Jacobites because of his religious and political affiliations, according to Maynard Mack, "where Pope himself stood on these matters can probably never be confidently known". These events led to an immediate downturn in the fortunes of the Tories, and Pope's friend Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke, fled to France. This was added to by the Impeachment of the former Tory Chief Minister [[Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer Article TalkLord Oxford]].

Pope lived in his parents' house in Mawson Row, Chiswick, between 1716 and 1719; the red-brick building is now the Mawson Arms, commemorating him with a blue plaque.[12]

The money made from his translation of Homer allowed Pope to move in 1719 to a villa at Twickenham, where he created his now-famous grotto and gardens. The serendipitous discovery of a spring during the excavation of the subterranean retreat enabled it to be filled with the relaxing sound of trickling water, which would quietly echo around the chambers. Pope was said to have remarked, "Were it to have nymphs as well – it would be complete in everything." Although the house and gardens have long since been demolished, much of the grotto survives beneath Radnor House Independent Co-educational School.[8][13] The grotto has been restored and will open to the public for 30 weekends a year from 2023 under the auspices of Pope's Grotto Preservation Trust.[14]

Poetry

Essay on Criticism

An Essay on Criticism was first published anonymously on 15 May 1711. Pope began writing the poem early in his career and took about three years to finish it.

At the time the poem was published, its heroic couplet style was quite a new poetic form and Pope's work an ambitious attempt to identify and refine his own positions as a poet and critic. It was said to be a response to an ongoing debate on the question ofa whether poetry should be natural, or written according to predetermined artificial rules inherited from the classical past.[15]

The "essay" begins with a discussion of the standard rules that govern poetry, by which a critic passes judgement. Pope comments on the classical authors who dealt with such standards and the authority he believed should be accredited to them. He discusses the laws to which a critic should adhere while analysing poetry, pointing out the important function critics perform in aiding poets with their works, as opposed to simply attacking them.[16] The final section of An Essay on Criticism discusses the moral qualities and virtues inherent in an ideal critic, whom Pope claims is also the ideal man.

The Rape of the Lock

Pope's most famous poem is The Rape of the Lock, first published in 1712, with a revised version in 1714. A mock-epic, it satirises a high-society quarrel between Arabella Fermor (the "Belinda" of the poem) and Lord Petre, who had snipped a lock of hair from her head without permission. The satirical style is tempered, however, by a genuine, almost voyeuristic interest in the "beau-monde" (fashionable world) of 18th-century society.[17] The revised, extended version of the poem focuses more clearly on its true subject: the onset of acquisitive individualism and a society of conspicuous consumers. In the poem, purchased artefacts displace human agency and "trivial things" come to dominate.[18]

The Dunciad and Moral Essays

Though The Dunciad first appeared anonymously in Dublin, its authorship was not in doubt. Pope pilloried a host of other "hacks", "scribblers" and "dunces" in addition to Theobald, and Maynard Mack has accordingly called its publication "in many ways the greatest act of folly in Pope's life". Though a masterpiece due to having become "one of the most challenging and distinctive works in the history of English poetry", writes Mack, "it bore bitter fruit. It brought the poet in his own time the hostility of its victims and their sympathizers, who pursued him implacably from then on with a few damaging truths and a host of slanders and lies."[19]

According to his half-sister Magdalen Rackett, some of Pope's targets were so enraged by The Dunciad that they threatened him physically. "My brother does not seem to know what fear is," she told Joseph Spence, explaining that Pope loved to walk alone, so went accompanied by his Great Dane Bounce, and for some time carried pistols in his pocket.[20] This first Dunciad, along with John Gay's The Beggar's Opera and Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels, joined in a concerted propaganda assault against Robert Walpole's Whig ministry and the financial revolution it stabilised. Although Pope was a keen participant in the stock and money markets, he never missed a chance to satirise the personal, social and political effects of the new scheme of things. From The Rape of the Lock onwards, these satirical themes appear constantly in his work.

In 1731, Pope published his "Epistle to Burlington", on the subject of architecture, the first of four poems later grouped as the Moral Essays (1731–1735).[21] The epistle ridicules the bad taste of the aristocrat "Timon".[22] For example, the following are verses 99 and 100 of the Epistle:

At Timon's Villa let us paſs a day,

Where all cry out, "What ſums are thrown away!"[22]

Pope's foes claimed he was attacking the Duke of Chandos and his estate, Cannons. Though the charge was untrue, it did much damage to Pope.[citation needed]

There has been some speculation on a feud between Pope and Thomas Hearne, due in part to the character of Wormius in The Dunciad, who is seemingly based on Hearne.[23]

An Essay on Man

An Essay on Man is a philosophical poem in heroic couplets published between 1732 and 1734. Pope meant it as the centrepiece of a proposed system of ethics to be put forth in poetic form. It was a piece that he sought to make into a larger work, but he did not live to complete it.[24] It attempts to "vindicate the ways of God to Man", a variation on Milton's attempt in Paradise Lost to "justify the ways of God to Man" (1.26). It challenges as prideful an anthropocentric worldview. The poem is not solely Christian, however. It assumes that man has fallen and must seek his own salvation.[24]

Consisting of four epistles addressed to Lord Bolingbroke, it presents an idea of Pope's view of the Universe: no matter how imperfect, complex, inscrutable and disturbing the Universe may be, it functions in a rational fashion according to natural laws, so that the Universe as a whole is a perfect work of God, though to humans it appears to be evil and imperfect in many ways. Pope ascribes this to our limited mindset and intellectual capacity. He argues that humans must accept their position in the "Great Chain of Being", at a middle stage between the angels and the beasts of the world. Accomplish this and we potentially could lead happy and virtuous lives.[24]

The poem is an affirmative statement of faith: life seems chaotic and confusing to man in the centre of it, but according to Pope it is truly divinely ordered. In Pope's world, God exists and is what he centres the Universe around as an ordered structure. The limited intelligence of man can only take in tiny portions of this order and experience only partial truths, hence man must rely on hope, which then leads to faith. Man must be aware of his existence in the Universe and what he brings to it in terms of riches, power and fame. Pope proclaims that man's duty is to strive to be good, regardless of other situations.[25][failed verification]

Later life and works

The Imitations of Horace that followed (1733–1738) were written in the popular Augustan form of an "imitation" of a classical poet, not so much a translation of his works as an updating with contemporary references. Pope used the model of Horace to satirise life under George II, especially what he saw as the widespread corruption tainting the country under Walpole's influence and the poor quality of the court's artistic taste. Pope added as an introduction to Imitations a wholly original poem that reviews his own literary career and includes famous portraits of Lord Hervey ("Sporus"), Thomas Hay, 9th Earl of Kinnoull ("Balbus") and Addison ("Atticus").

In 1738 came the Universal Prayer.[26]

Among the younger poets whose work Pope admired was Joseph Thurston.[27] After 1738, Pope himself wrote little. He toyed with the idea of composing a patriotic epic in blank verse called Brutus, but only the opening lines survive. His major work in those years was to revise and expand his masterpiece, The Dunciad. Book Four appeared in 1742 and a full revision of the whole poem the following year. Here Pope replaced the "hero" Lewis Theobald with the Poet Laureate, Colley Cibber as "king of dunces". However, the real focus of the revised poem is Walpole and his works. By now Pope's health, which had never been good, was failing. When told by his physician, on the morning of his death, that he was better, Pope replied: "Here am I, dying of a hundred good symptoms."[28][29] He died at his villa surrounded by friends on 30 May 1744, about eleven o'clock at night. On the previous day, 29 May 1744, Pope had called for a priest and received the Last Rites of the Catholic Church. He was buried in the nave of St Mary's Church, Twickenham.

Translations and editions

The Iliad

Pope had been fascinated by Homer since childhood. In 1713, he announced plans to publish a translation of the Iliad. The work would be available by subscription, with one volume appearing every year over six years. Pope secured a revolutionary deal with the publisher Bernard Lintot, which earned him 200 guineas (£210) a volume, a vast sum at the time.

His Iliad translation appeared between 1715 and 1720. It was acclaimed by Samuel Johnson as "a performance which no age or nation could hope to equal" (though the classical scholar Richard Bentley wrote: "It is a pretty poem, Mr. Pope, but you must not call it Homer.")[30]

The Odyssey

Encouraged by the success of the Iliad, Bernard Lintot published Pope's five-volume translation of Homer's Odyssey in 1725–1726.[31] For this Pope collaborated with William Broome and Elijah Fenton: Broome translated eight books (2, 6, 8, 11, 12, 16, 18, 23), Fenton four (1, 4, 19, 20) and Pope the remaining 12. Broome provided the annotations.[32] Pope tried to conceal the extent of the collaboration, but the secret leaked out.[33] It did some damage to Pope's reputation for a time, but not to his profits.[34] Leslie Stephen considered Pope's portion of the Odyssey inferior to his version of the Iliad, given that Pope had put more effort into the earlier work – to which, in any case, his style was better suited.[35]

Shakespeare's works

In this period, Pope was employed by the publisher Jacob Tonson to produce an opulent new edition of Shakespeare.[36] When it appeared in 1725, it silently regularised Shakespeare's metre and rewrote his verse in several places. Pope also removed about 1,560 lines of Shakespeare's material, arguing that some appealed to him more than others.[36] In 1726, the lawyer, poet and pantomime-deviser Lewis Theobald published a scathing pamphlet called Shakespeare Restored, which catalogued the errors in Pope's work and suggested several revisions to the text. This enraged Pope, wherefore Theobald became the main target of Pope's Dunciad.[37]

The second edition of Pope's Shakespeare appeared in 1728.[36] Apart from some minor revisions to the preface, it seems that Pope had little to do with it. Most later 18th-century editors of Shakespeare dismissed Pope's creatively motivated approach to textual criticism. Pope's preface continued to be highly rated. It was suggested that Shakespeare's texts were thoroughly contaminated by actors' interpolations and they would influence editors for most of the 18th century.

Spirit, skill and satire

Pope's poetic career testifies to an indomitable spirit despite disadvantages of health and circumstance. The poet and his family were Catholics and so fell subject to the prohibitive Test Acts, which hampered their co-religionists after the abdication of James II. One of these banned them from living within ten miles of London, another from attending public school or university. So except for a few spurious Catholic schools, Pope was largely self-educated. He was taught to read by his aunt and became a book lover, reading in French, Italian, Latin and Greek and discovering Homer at the age of six. In 1700, when only twelve years of age, he wrote his poem Ode on Solitude.[38][39] As a child Pope survived once being trampled by a cow, but when he was 12 he began struggling with tuberculosis of the spine (Pott disease), which restricted his growth, so that he was only 4 feet 6 inches (1.37 metres) tall as an adult. He also suffered from crippling headaches.

In the year 1709, Pope showcased his precocious metrical skill with the publication of Pastorals, his first major poems. They earned him instant fame. By the age of 23, he had written An Essay on Criticism, released in 1711. A kind of poetic manifesto in the vein of Horace's Ars Poetica, it met with enthusiastic attention and won Pope a wider circle of prominent friends, notably Joseph Addison and Richard Steele, who had recently begun to collaborate on the influential The Spectator. The critic John Dennis, having found an ironic and veiled portrait of himself, was outraged by what he saw as the impudence of a younger author. Dennis hated Pope for the rest of his life, and save for a temporary reconciliation, dedicated his efforts to insulting him in print, to which Pope retaliated in kind, making Dennis the butt of much satire.

A folio containing a collection of his poems appeared in 1717, along with two new ones about the passion of love: Verses to the Memory of an Unfortunate Lady and the famous proto-romantic poem Eloisa to Abelard. Though Pope never married, about this time he became strongly attached to Lady M. Montagu, whom he indirectly referenced in his popular Eloisa to Abelard, and to Martha Blount, with whom his friendship continued through his life.

As a satirist, Pope made his share of enemies as critics, politicians and certain other prominent figures felt the sting of his sharp-witted satires. Some were so virulent that Pope even carried pistols while walking his dog. In 1738 and thenceforth, Pope composed relatively little. He began having ideas for a patriotic epic in blank verse titled Brutus, but mainly revised and expanded his Dunciad. Book Four appeared in 1742; and a complete revision of the whole in the year that followed. At this time Lewis Theobald was replaced with the Poet Laureate Colley Cibber as "king of dunces", but his real target remained the Whig politician Robert Walpole.

Reception

By the mid-18th century, new fashions in poetry emerged. A decade after Pope's death, Joseph Warton claimed that Pope's style was not the most excellent form of the art. The Romantic movement that rose to prominence in early 19th-century England was more ambivalent about his work. Though Lord Byron identified Pope as one of his chief influences – believing his own scathing satire of contemporary English literature English Bards and Scotch Reviewers to be a continuance of Pope's tradition – William Wordsworth found Pope's style too decadent to represent the human condition.[4] George Gilfillan in an 1856 study called Pope's talent "a rose peering into the summer air, fine, rather than powerful".[40]

Pope's reputation revived in the 20th century. His work was full of references to the people and places of his time, which aided people's understanding of the past. The post-war period stressed the power of Pope's poetry, recognising that Pope's immersion in Christian and Biblical culture lent depth to his poetry. For example, Maynard Mack, in the late 20th-century, argued that Pope's moral vision demanded as much respect as his technical excellence. Between 1953 and 1967 the definitive Twickenham edition of Pope's poems appeared in ten volumes, including an index volume.[4]

Works

Major works

- 1709: Pastorals

- 1711: An Essay on Criticism[41]

- 1712: Messiah (from the Book of Isaiah, and later translated into Latin by Samuel Johnson)

- 1712: The Rape of the Lock (enlarged in 1714)[41]

- 1713: Windsor Forest[6][41]

- 1715: The Temple of Fame: A Vision[42]

- 1717: Eloisa to Abelard[41]

- 1717: Three Hours After Marriage, with others

- 1717: Elegy to the Memory of an Unfortunate Lady[41]

- 1728: Peri Bathous, Or the Art of Sinking in Poetry

- 1728: The Dunciad[41]

- 1731–1735: Moral Essays

- 1733–1734: Essay on Man[41]

- 1735: Epistle to Dr Arbuthnot

Translations and editions

- 1715–1720: Translation of the Iliad[41]

- 1723–1725: The Works of Shakespear, in Six Volumes

- 1725–1726: Translation of the Odyssey[41]

Other works

- 1700: Ode on Solitude

- 1713: Ode for Musick[43]

- 1715: A Key to the Lock

- 1717: The Court Ballad[44]

- 1717: Ode for Music on St. Cecilia's Day

- 1731: An Epistle to the Right Honourable Richard Earl of Burlington[45]

- 1733: The Impertinent, or A Visit to the Court[46]

- 1736: Bounce to Fop[47]

- 1737: The First Ode of the Fourth Book of Horace[48]

- 1738: The First Epistle of the First Book of Horace[49]

Editions

See also

References

- ^ "Alexander Pope: The Evolution of a Poet" by Netta Murray Goldsmith (2002), p. 17: "Alexander Pope was born on Monday 21 May 1688 at 6.45 pm when England was on the brink of a revolution."

- ^ Foundation, Poetry (29 April 2021). "Alexander Pope". Poetry Foundation. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Erskine-Hill, Howard (2004). "Pope, Alexander (1688–1744)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/22526 (subscription required)

- ^ a b c d e f g "Alexander Pope", Literature Online biography (Chadwyck-Healey: Cambridge, 2000). (subscription required)

- ^ "An Act to prevent and avoid dangers which may grow by Popish Recusants" (3 Jas. 1. c. 4). For details, see Catholic Encyclopedia, "Penal Laws Archived 6 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine".

- ^ a b c Pope, Alexander. Windsor-Forest Archived 17 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA).

- ^ Rumbold, Valerie (1989). Women's Place in Pope's World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 33, 48, 128.

- ^ a b Gordon, Ian (24 January 2002). "An Epistle to a Lady (Moral Essay II)". The Literary Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 7 October 2007. Retrieved 17 April 2009.

- ^ "Martha Blount". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2009. Archived from the original on 30 January 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2009.

- ^ The Life of Alexander Pope, by Robert Carruthers, 1857, with a corrupted and badly scanned version available from Internet Archive, or as an even worse 23MB PDF. For reference to his relationship with Martha Blount and her sister, see pp. 64–68 (p. 89 ff. of the PDF). In particular, discussion of the controversy over whether the relationship was sexual is described in some detail on pp. 76–78.

- ^ Zachary Cope (1953) William Cheselden, 1688–1752. Edinburgh: E. & S. Livingstone, p. 89.

- ^ Clegg, Gillian. "Chiswick History". People: Alexander Pope. chiswickhistory.org.uk. Archived from the original on 20 September 2011. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- ^ London Evening Standard, 2 November 2010.

- ^ Fox, Robin Lane (23 July 2021). "The secrets and lights of Alexander Pope's Twickenham grotto". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ Rogers, Pat (2006). The Major Works. Oxford University Press. pp. 17–39. ISBN 019920361X.

- ^ Baines, Paul (2001). The Complete Critical Guide to Alexander Pope. Routledge Publishing. pp. 67–90.

- ^ "from the London School of Journalism". Archived from the original on 31 May 2008.

- ^ Colin Nicholson (1994). Writing and the Rise of Finance: Capital Satires of the Early Eighteenth Century, Cambridge.

- ^ Maynard Mack (1985). Alexander Pope: A Life. W. W. Norton & Company, and Yale University Press, pp. 472–473. ISBN 0393305295

- ^ Joseph Spence. Observations, Anecdotes, and Characters of Books and Men, Collected from the Conversation of Mr. Pope (1820), p. 38 Archived 2 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Moral Essays". Archived from the original on 9 August 2021. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ^ a b Alexander Pope. Moral Essays Archived 21 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, p. 82

- ^ Rogers, Pat (2004). The Alexander Pope encyclopedia. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-06153-X. OCLC 607099760.

- ^ a b c Nuttal, Anthony (1984). Pope's Essay on Man. Allen & Unwin. pp. 3–15, 167–188. ISBN 9780048000170.

- ^ Cassirer, Ernst (1944). An Essay on Man; an introduction to a philosophy of human culture. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300000344.

- ^ McKeown, Trevor W. "Alexander Pope 'Universal Prayer'". bcy.ca. Archived from the original on 28 January 2017. Retrieved 12 April 2007. Full-text Archived 17 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Also at the Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA).

- ^ James Sambrook (2004) "Thurston, Josephlocked (1704–1732)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/70938

- ^ Ruffhead, Owen (1769). The Life of Alexander Pope; With a Critical Essay on His Writings and Genius. p. 475.

- ^ Dyce, Alexander (1863). The Poetical Works of Alexander Pope, with a Life, by A. Dyce. p. cxxxi.

- ^ Johnson, Samuel (1791). The Lives of the Most Eminent Poets with Critical Observations on their Works. Vol. IV. London: Printed for J. Rivington & Sons, and 39 others. p. 193. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ Homer (1725–1726). The Odyssey of Homer. Translated by Alexander Pope; William Broome & Elijah Fenton (1st ed.). London: Bernard Lintot.

- ^ Fenton, Elijah (1796). The poetical works of Elijah Fenton with the life of the author. Printed for, and under the direction of, G. Cawthorn, British Library, Strand. p. 7. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- ^ Fraser, George (1978). Alexander Pope. Routledge. p. 52. ISBN 9780710089908.

- ^ Damrosch, Leopold (1987). The Imaginative World of Alexander Pope. University of California Press. p. 59. ISBN 9780520059757.

- ^ Stephen, Sir Leslie (1880). Alexander Pope. Harper & Brothers. pp. 80.

- ^ a b c "Preface to Shakespeare, 1725, Alexander Pope". ShakespeareBrasileiro. Archived from the original on 11 January 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ "Lewis Theobald" Archived 14 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- ^ Genetic studies of genius by Lewis Madison Terman Stanford University Press, 1925 OCLC: 194203

- ^ "Personhood, Poethood, and Pope: Johnson's Life of Pope and the Search for the Man Behind the Author" by Mannheimer, Katherine. Eighteenth-Century Studies - Volume 40, Number 4, Summer 2007, pp. 631-649 MUSE Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ George Gilfillan (1856) "The Genius and Poetry of Pope", The Poetical Works of Alexander Pope, Vol. 11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Cox, Michael, editor, The Concise Oxford Chronology of English Literature, Oxford University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-19-860634-6

- ^ Alexander Pope (1715) The Temple of Fame: A Vision. London: Printed for Bernard Lintott. Print.

- ^ Pope, Alexander. ODE FOR MUSICK. Archived 17 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA).

- ^ Pope, Alexander. The Court Ballad Archived 17 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA).

- ^ Pope, Alexander. Epistle to Richard Earl of Burlington Archived 17 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA).

- ^ Pope, Alexander. The IMPERTINENT, or A Visit to the COURT. A SATYR. Archived 17 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA).

- ^ Pope, Alexander. Bounce to Fop Archived 17 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA).

- ^ Pope, Alexander. THE FIRST ODE OF THE FOURTH BOOK OF HORACE. Archived 17 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA).

- ^ Pope, Alexander. THE FIRST EPISTLE OF THE FIRST BOOK OF HORACE. Archived 17 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA).

Bibliography

- Davis, Herbert, ed. (1966). Poetical Works. Oxford Standard Authors. London: Oxford U.P.

- Mack, Maynard (1985). Alexander Pope. A Life. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Hans Ostrom (1878) "Pope's Epilogue to the Satires, 'Dialogue I'." Explicator, 36:4, pp. 11–14.

- Rogers, Pat (2007). The Cambridge Companion to Alexander Pope. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Alexander Pope at the Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA)

- Works by Alexander Pope at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Alexander Pope at the Internet Archive

- Works by Alexander Pope at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- John Wilkes and Alexander Pope – UK Parliament Living Heritage

- Lennox, Patrick Joseph (1911). . Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 12.

- Minto, William; Bryant, Margaret (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). pp. 82–87.

- BBC audio file. In Our Time, radio 4 discussion of Pope.

- University of Toronto "Representative Poetry Online" page on Pope

- Pope's Grave

- The Twickenham Museum Archived 14 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Pope's Grotto Preservation Trust

- Richmond Libraries' Local Studies Collection. Local History. Accessed 2010-10-19

- "Archival material relating to Alexander Pope". UK National Archives.

- Portraits of Alexander Pope at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Images relating to Alexander Pope Archived 31 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine at the English Heritage Archive

- Blue Plaque at 110 Chiswick Lane South, Chiswick, London W4 2LR

- 1688 births

- 1744 deaths

- 18th-century deaths from tuberculosis

- 18th-century English poets

- 18th-century English non-fiction writers

- 18th-century English male writers

- 18th-century essayists

- Burials at St Mary's Church, Twickenham

- English Catholic poets

- English essayists

- English male poets

- English Roman Catholics

- British male essayists

- Neoclassical writers

- People educated at Twyford School

- People from Binfield

- People from the City of London

- Roman Catholic writers

- Works by Alexander Pope

- Freemasons of the Premier Grand Lodge of England

- Tory poets

- English male non-fiction writers

- Translators of Homer

- English landscape and garden designers

- Tuberculosis deaths in England