Erromango

Native name: Nelocopne | |

|---|---|

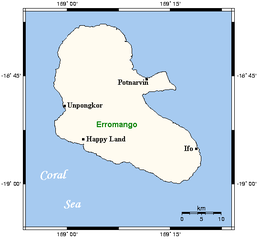

Map of Erromango Island | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Coral Sea |

| Coordinates | 18°48′50″S 169°07′22″E / 18.81389°S 169.12278°E |

| Archipelago | Vanuatu |

| Area | 891.9 km2 (344.4 sq mi) |

| Length | 48 km (29.8 mi) |

| Width | 30 km (19 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 886 m (2907 ft) |

| Highest point | Mount Santop |

| Administration | |

| Province | Tafea Province |

| Largest settlement | Upogkor |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 2,084 (2009) |

| Pop. density | 2.34/km2 (6.06/sq mi) |

| Languages | Sie, Bislama, English, French, Ura (moribund), formerly Utaha and Sorung |

| Ethnic groups | Ni-Vanuatu |

| Additional information | |

| Time zone |

|

Erromango is the fourth largest island in the Vanuatu archipelago. With a land area of 891.9 square kilometres (344.4 sq mi), it is the largest island in Tafea Province, the southernmost of Vanuatu's six administrative regions.

Name

The endonym for Erromango in Erromangan is Nelocompne. There are several accounts of how 'Erromango' came into common usage: firstly, an oral history from the Potnarvin area tells of how Captain James Cook was given a yam during his visit in August 1774, and was told in the (now-extinct) Sorung language armai n'go, armai n'go ('this food is good'), and mistakenly assumed this to be the name of the island.[1] A second account is related by the naturalist Georg Forster, who accompanied Cook. He writes that he learned the name 'Irromanga' from a man named Fannòko, while visiting the neighbouring island of Tanna five days later.[2] Cook himself does not name the island in his account of his visit, but writes later that he got the name, which he spells as 'Erromango', from Forster.[3]

History

Prehistory

Erromango was first settled by humans around 3,000 years ago, as part of the Lapita migration out of south-east Asia into island Melanesia. The Lapita people brought with them domestic animals such as pigs and chickens[4] and food plants such as yam[5] and breadfruit.[6]

Two sites on Erromango, Ifo and Ponamla, have yielded significant archaeological evidence of habitation by Lapita and post-Lapita peoples, including pottery sherds, adzes, marine shell artifacts and cooking stones.[7]

Erromango contains numerous caves that provided refuge from tribal warfare and cyclones. Human use of these caves has been dated to 2,800-2,400 years before the present.[8] Some of the caves contain rock art and petroglyphs that have been identified with clan motifs and traditional stories. Caves were also used as burial sites.[9]

European contact

James Cook was the first European to land on Erromango, landing near present-day Potnarvin in the north-east on 4 August 1774. Cook and his landing party were set upon by a group of local men, and in the scuffle that followed, several of Cook's men were injured and a number of Erromangans killed. Following this incident, Cook gave the name 'Traitor's head' to the peninsula adjacent to Potnarvin.[10]

Whaling vessels were among the early regular visitors to the island on the nineteenth century. The first such vessel known to have visited was the Rose in 1804 and the last on record was the American vessel John & Winthrop in 1887.[11]

The sandalwood trade

In 1825, trader and adventurer Peter Dillon discovered the island's large reserves of sandalwood (Santalum austrocaledonicum), valued in China for its aromatic oil and as a carving wood. Dillon found that his trade goods were not sufficient to entice Erromangans to cut the timber for him, so he left without gathering any sandalwood. News of his discovery brought other outsiders to Erromango to exploit the resource, and this caused conflict between the Erromangans and the traders.[12]

In 1830, King Kamehameha III of Hawaii sent two ships with 479 Hawaiians on board to seize control of Erromango and its sandalwood, under the command of Boki, ruler-designate of Erromango. Their arrival in Cook's Bay coincided with the arrival of two other groups of traders intent on exploiting the sandalwood; two ships, the Dhaule and the Sophia, both crewed by 330 Rotuman labourers and another ship, the Snapper, with a crew of 113 Tongan labourers on board, had all arrived just before the Hawaiian vessels. The Erromangans resisted the Hawaiians' takeover attempt, and the Hawaiians' hostile intent turned the Erromangans against the other interlopers and their Polynesian crews. Fever killed most of the Tongan and Hawaiian labourers, and just 20 Hawaiians returned to Hawaii to tell the story of their failed occupation. A crash in the price of sandalwood shortly after deterred most traders until the mid-1840s, but even when prices rose again, the combined risks of attack on shore, uncharted reefs, storms and hurricanes meant that sandalwood trading was a highly speculative venture. Some traders such as Robert Towns and James Paddon established stations on Erromango or nearby islands such as Aneityum and Île des Pins in New Caledonia to reduce their costs. By 1865 though, Erromango's sandalwood resource was exhausted.[13]

Introduced diseases and depopulation

Erromango's population prior to European contact is estimated at approximately 5,000,[14] though some estimates are as high as 20,000. European visitors brought diseases such as influenza, smallpox and measles to which the local population had no immunity. Sixty percent of Erromangans died during a smallpox outbreak in 1853 and a measles epidemic in 1861.[15]

Contemporary accounts by missionaries blamed the sandalwood traders for the outbreaks.[16] Erromangans sought reprisal by killing European and Polynesian missionaries such as George N. Gordon, their converts, and other visitors.[17][18][19]

The labour trade and blackbirding

Between 1863 and 1906, around 40,000 people from what was then the New Hebrides were blackbirded onto ships to work as indentured labour on cotton and sugarcane plantations in Queensland, Australia. Another 10,000 went to work in nickel mines in New Caledonia and on plantations in Fiji, Samoa and Hawaii.[20] Many of the islanders recruited were duped into taking part; some were coerced, and some volunteered. While some Erromangan names are listed in official records of Melanesian labourers in Queensland,[21] no exact figures exist for the number of Erromangans who were blackbirded. However, 25 years after the White Australia Policy ended the Melanesian labour trade in 1906, Erromango's population had dwindled to just 381.[22]

Missions and Cannibals

John Williams of the London Missionary Society and fellow missionary James Harris were killed and eaten by cannibals at Dillons Bay in November 1839.[23] In November 2009, after a lengthy collaboration between the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia, the Presbyterian church of Vanuatu and the Vanuatu Cultural Centre, Williams' descendants travelled to Erromango to reconcile with the descendants of those who killed their ancestor, the Uswo-Natgo clan, 170 years earlier.[24] To mark the occasion, Dillons Bay was renamed Williams Bay.[25][26]

The Rev. George Nicol Gordon, of Prince Edward Island, Canada and his wife, Ellen Catherine Powell, missionaries from the Presbyterian Church of Nova Scotia to the New Hebrides, were killed at Dillons Bay on May 20, 1861. A memoir of the couple appeared in book form, at Halifax, Nova Scotia in 1863.[27]

In total, six missionaries were killed on Erromango.[28] An oral history from Unpogkor (Dillons Bay) says Rev. Williams was killed because he disrespected an important kastom ceremony that was taking place when he landed.[29] The Boy's Own Paper (1879) states that Rev. Williams and a Mr. Harris (identified as a man traveling to England to become a missionary) were killed because they arrived on the island shortly after an "outrage" was committed by the crew of another vessel. (The nature of this "outrage" is not stated in the article.) The pair, realizing their danger, died during a failed attempt to escape the island, being killed by natives on shore a few yards from their boat.

As Williams was the first Christian martyr in the south Pacific, Erromango became a particular focus for missionisation.[30] Another missionary, Reverend McNair and his wife, were present on the island at Dillon's Bay until the former's death from illness in 1871. A Royal Navy captain visiting in 1869 described the conditions there as difficult, with scarce supplies of flour, clouds of mosquitoes, murderous threats from natives, and a "sweltering poisonous atmosphere, accompanied by fever and ague."[31]

Canadian Presbyterian missionary H.A. Robertson, resident on Erromango from 1872–1913, succeeded in missionising the island's population. This changed the traditional society of the island. His attempts at missionisation were effective because he carefully studied the beliefs and material culture in order to target the most powerful symbols of traditional society. He collected many objects and sent them to overseas museums or used them as curios in his overseas fundraising tours to demonstrate the 'backwardness' of Erromangans.[32]

In 1902, Robertson published Erromanga: the Martyr Isle, his description of his life as a missionary on the island. It was the first popular account[33] of Erromango and its people. It promoted to a global audience the idea that Erromango was the 'Martyr's Island'.[34]

Robertson's predecessor, Rev. James D. Gordon, had spread the belief amongst Erromangans that the Christian God had sent the 1861 measles epidemic to punish them for the killing of Rev. Williams and the other missionaries. Gordon saw this as a means of gaining converts, though some of his contemporaries disapproved of this tactic.[35] This tactic backfired on Gordon, as he and his wife were killed in reprisal for the epidemic, which continued unabated despite their deaths. Over time, Gordon's myth grew into a collective belief amongst Erromangans that the island had been cursed by the Presbyterian Church. This caused the abandonment of forms of cultural expression not sanctioned by the church.[36] Belief in this 'curse' endured until the 2009 reconciliation ceremony, which initiated a re-examination of Erromango's history and culture from an Erromangan point of view. According to a participant, "the reconciliation has freed us up to embrace our customs and traditions, which we couldn't do before because of the guilt attached to Erromango's history and the tendency to view traditional culture as the antithesis of Christianity".[37]

Later history

Erromango and nearby Tanna were devastated by cyclone Pam in mid-March 2015, with reports from Tanna of an unknown number of deaths, complete destruction of the island's infrastructure and permanent shelters, no drinking water.[38]

Geography

The total area of Erromango is 891.9 km². It measures approximately 48 km from the north-west tip to the south-east, and is between 20 and 30 kilometres wide. Its highest point is Mount Santop, at 886m. The island is situated between latitude 18°37'S and 18°59'S and 168°59'E and 168°20'E.[39] Vete Manung Island is located 15 km off the north-east coast of Erromango.[40]

In the middle of the east coast is a promontory formed by the volcanic cone of Mount Rantop. 6 km off the east coast is an uninhabited islet named Vetemanu (English name Goat Island) of approximately 12ha in area.[41]

The island is part of the Vanuatu rainforests ecoregion, within the East Melanesian Islands biogeographic region. Dense evergreen forest covers nearly three-quarters of the island on the windward (eastern) side, while a combination of grassland and woodland occupies the north-west. Cloud forests exist at higher elevations. Much of the vegetation on the island is secondary growth.[42]

Formerly it was known as a source of sandalwood in the 19th century, and much of it was depleted. It is also home to the kauri and tamanu trees. There has been extensive logging, but most of the area is recovering, and efforts are underway to try to make the industry sustainable. With European Union support, there is a protected Happy Lands Kauri Reserve.

Climate

| Climate data for Erromango (elevation 198 m) (1949-2019) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 32.5 (90.5) |

32.0 (89.6) |

32.0 (89.6) |

31.2 (88.2) |

30.7 (87.3) |

28.9 (84.0) |

27.8 (82.0) |

28.3 (82.9) |

30.2 (86.4) |

31.1 (88.0) |

32.5 (90.5) |

31.7 (89.1) |

32.5 (90.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 27.9 (82.2) |

28.5 (83.3) |

27.4 (81.3) |

26.5 (79.7) |

25.6 (78.1) |

24.3 (75.7) |

23.5 (74.3) |

23.7 (74.7) |

24.4 (75.9) |

26.2 (79.2) |

27.0 (80.6) |

27.7 (81.9) |

26.0 (78.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 25.3 (77.5) |

25.7 (78.3) |

25.1 (77.2) |

24.1 (75.4) |

23.1 (73.6) |

22.0 (71.6) |

21.1 (70.0) |

21.0 (69.8) |

21.8 (71.2) |

23.1 (73.6) |

24.1 (75.4) |

25.0 (77.0) |

23.5 (74.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 22.6 (72.7) |

22.9 (73.2) |

22.7 (72.9) |

21.6 (70.9) |

20.7 (69.3) |

19.8 (67.6) |

18.7 (65.7) |

18.3 (64.9) |

19.2 (66.6) |

20.0 (68.0) |

21.3 (70.3) |

22.2 (72.0) |

20.8 (69.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 17.8 (64.0) |

19.0 (66.2) |

17.8 (64.0) |

16.7 (62.1) |

16.1 (61.0) |

14.4 (57.9) |

12.8 (55.0) |

12.8 (55.0) |

13.9 (57.0) |

14.4 (57.9) |

16.7 (62.1) |

16.1 (61.0) |

12.8 (55.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 308.5 (12.15) |

165.9 (6.53) |

371.1 (14.61) |

148.7 (5.85) |

167.0 (6.57) |

94.4 (3.72) |

107.0 (4.21) |

79.2 (3.12) |

89.2 (3.51) |

67.9 (2.67) |

95.3 (3.75) |

285.0 (11.22) |

1,979.2 (77.91) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 18.1 | 15.3 | 20.2 | 14.4 | 11.5 | 12.2 | 11.2 | 7.9 | 9.9 | 6.2 | 11.3 | 15.7 | 154.0 |

| Source: NOAA[43] | |||||||||||||

Geology

Erromango, like most other islands of the Vanuatu archipelago, is volcanic in origin.[44] It is composed of basalt and andesite from the late Miocene-Recent periods and is situated along a Pliocene-Recent volcanic chain that is moving to the north-northwest.[45] Most of the island is fringed with a platform of uplifted coral reef limestone dating from the Late Pleistocene and Holocene.[46]

Volcanism

Erromango was formed during a prolonged period of volcanic activity took place between 6-1 Ma.[47] The island is an ancient underwater volcano that has been raised 100-300m above sea level by tectonic uplift, forming a plateau on which stand three sets of eroded volcanic cones in the centre, north and east of the island. The centre is divided into two volcanoes; Mount Melkum (758m) to the west, and Nompun Umpan (802m) to the east. In the north of the island, Mount William (682m) is a strombolian cone with a caldera 6 km wide and around 600m deep.[48] The eastern peninsula that forms Traitor's Head, north of Cook's Bay on the east coast, is the youngest volcanic formation on the island and consists of four stratovolcanoes (Urap, Ulenu, Rantop and Wahous). A submarine volcano between the peninsula and nearby Vetemanu last erupted in 1881.[49]

Population

Erromango's population at the last census in 2009 was 1,959.[50] The annual population growth rate is 2.2%,[51] and there are a total of 325 private households[52] on the island. The largest villages are Dillons Bay (Upogkor), Potnarvin and Ipota.

Languages

Erromango was linguistically diverse prior to European contact. Since contact, however, Erromango has lost between 67% and 83% of its original languages. The island "has the dubious honour of having suffered the greatest amount of linguistic devastation in the region of Oceania outside of Australia", according to Pacific linguist Terry Crowley.[53]

While the original distribution of languages is not well documented, there were originally at least four distinct Erromangan languages: Enyau/Yocu, Ura (also known as Aryau), Utaha (also known as Etiyo or Ifo) and Sorug/Sye (also spelt Sie or Siye).[54] Sorug and Utaha are now extinct[55] and only a few elderly Ura speakers remain.[56] These four languages constitute the Erromanga branch of South Vanuatu languages.

Due to a lack of documentation, it is unclear whether Sorug and Sye were two distinct languages or whether they were dialects of a single language. There is also evidence of two additional speech forms, Novulamleg and Uravat, though it is not known whether these were dialectical variants, distinct languages, place or area names, names of descent groups or simply descriptive names.[57]

The depopulation that followed the series of epidemics of the mid-19th century resulted in a linguistic realignment. Villages that were no longer viable because of population loss either relocated or amalgamated with others, and the island's population dispersed. Yocu/Enyau was the dominant language during the late 19th century, as it was the language of the Dillons Bay area where the missionaries were based, and the language used in the first missionary bibles.[58]

Enyau/Yocu and Sorug/Sye merged between the 1870s and 1920s to become modern Erromangan.[59] Some linguists call this language Sye, however on Erromango nam Eromaga ('Erromangan language') is more common.[60]

Erromangan is spoken as the first language in 90.4% of Erromango's households.[61] Of Erromangans over the age of five, 63.6%[62] are literate in Bislama, Vanuatu's lingua franca. 62.3%[63] are literate in English and 19.0%[64] are literate in French, Vanuatu's two official languages.

Transportation

The island is served by two airstrips: Dillon's Bay Airport in the west and Ipota Airport in the east.

References

- ^ Huffman, Kirk (1996). "The 'Decorated Cloth' from the 'Island of Good Yams': Barkcloth in Vanuatu, with Special Reference to Erromango". In Bonnemaison, Joël; Huffman, Kirk; Kaufmann, Christian; et al. (eds.). Arts of Vanuatu. Bathurst: Crawford House Publishing. p. 129. ISBN 1-86333-142-5.

- ^ Forster, Georg; Thomas, Nicholas; Berghof, Oliver (2000). A Voyage Round the World. Vol. 1. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 520. ISBN 0824820916.

- ^ Cook, James (1890). The three famous voyages of Captain James Cook round the world. Vol. 1. London: Ward, Lock & Co. pp. 502–506, 509. Retrieved 2014-12-03.

- ^ Spriggs, Matthew (2006). "6: The Lapita Culture and Austronesian Prehistory in Oceania". In Bellwood, Peter; Fox, James J.; Tryon, Darrell (eds.). The Austronesians. Canberra: Australian National University Press. p. 124. ISBN 1-920942-85-8. Retrieved 2014-12-05.

- ^ Walter, Annie; Lebot, Vincent (2006). Gardens of Oceania. Canberra: Australian Centre for International Agriculture Research. pp. 71–72. ISBN 1-86320-513-6. Retrieved 2014-12-05.

- ^ Walter & Lebot 2006, p. 118.

- ^ Bedford, Stuart (1999). "Lapita and post-Lapita ceramic sequences from Erromango, southern Vanuatu". In Galipaud, Jean-Christophe; Lilley, Ian (eds.). Le Pacifique de 5000 à 2000 avant le présent : suppléments à l'histoire d'une colonisation (The Pacific from 5000 to 2000 BP : colonisation and transformations). Paris: Institut de recherche pour le développement. pp. 127–137. ISBN 2-7099-1431-X. Retrieved 2014-12-05.

- ^ Wilson, Meredith (2002). "1". Picturing Pacific Prehistory: The rock-art of Vanuatu in a western Pacific (Ph.D.). Australian National University, School of Archaeology and Anthropology. p. 128. hdl:1885/9161.

- ^ Naupa, Anna, ed. (2011). "Ch. 2: Traditional life". Nompi en Ovoteme Erromango (Kastom and culture of Erromango). Port Vila: Erromango Cultural Association. p. 20. ISBN 9789829132017.

- ^ Cook 1890, p. 503.

- ^ Langdon, Robert (1984) Where the whalers went: an index to the Pacific ports and islands visited by American whalers (and some other ships) in the 19th century, Canberra, Pacific Manuscripts Bureau, p.190. ISBN 086784471X

- ^ Dillon, letter to the editor, Bengal Herkaru, 14 October 1826, cited in Dorothy Shineberg, They Came for Sandalwood, Ch. 2 Beginnings of the Trade, University of Queensland Press 1967.

- ^ Shineberg 1967, Ch. 11.

- ^ Lightner, Sara; Naupa, Anna (2005). "4. A Century of Population Decrease: 1820s to 1920s". Histri Blong Yumi Long Vanuatu: an educational resource. Vol. 2. Port Vila: Vanuatu National Cultural Council. p. 91. ISBN 982-9032-07-8.

- ^ Carillo-Huffman & Nemban 2010, p.90.

- ^ Paton, John G., Missionary to the New Hebrides: An Autobiography (1889; reprint; Ross-shire, Great Britain: Christian Focus, 2009), pp. 111-114, 123.

- ^ Shineberg 1967, pp. 175-176.

- ^ The last martyrs of Eromanga : being a memoir of the Rev. George N. Gordon and Ellen Catherine Powell, his wife by Gordon, James Douglas, 1863

- ^ Paton, John G., Missionary to the New Hebrides: An Autobiography (1889; reprint; Ross-shire, Great Britain: Christian Focus, 2009), pp. 123-125.

- ^ Lighter & Naupa 2005, p. 41

- ^ "Australian South Sea Islanders 1867 to 1908" (csv). Queensland Government data. Queensland Government. Retrieved 2014-12-05.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Crowley 1997, p. 34.

- ^ Paton, John G., Missionary to the New Hebrides: An Autobiography (1889; reprint; Ross-shire, Great Britain: Christian Focus, 2009), p. 56.

- ^ Naupa 2011, p. 98.

- ^ 18°49′00″S 169°00′30″E / 18.81667°S 169.00833°E

- ^ "BBC News - Island holds reconciliation over cannibalism". news.bbc.co.uk. 2009-12-07. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ^ Morgan, Henry James, ed. (1903). Types of Canadian Women and of Women who are or have been Connected with Canada. Toronto: Williams Briggs. p. 132.

- ^ Shineberg 1967, Ch. 16.

- ^ Naupa 2011, p. 94.

- ^ Carillo-Huffman & Nemban 2010, p.101.

- ^ Palmer, George (1871). Kidnapping in the South Seas: Being a Narrative of a Three Months' Cruise of H. M. Ship Rosario. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas. pp. 54–64.

- ^ Carillo-Huffman & Nemban 2010, p.93.

- ^ "Savages of the New Hebrides" (PDF). The New York Times. New York. March 21, 1903. Retrieved 2014-12-05.

- ^ Carillo-Huffman & Nemban 2010, p.94.

- ^ Shineberg 1967, ch. 16.

- ^ Carillo-Huffman & Nemban 2010, p.91.

- ^ Mayer, Carol E.; Naupa, Anna; Warri, Vanessa (2013). No Longer Captives of the Past : the story of a reconciliation on Erromango. Port Vila/Vancouver: Erromango Cultural Association/Museum of Anthropology, University of British Columbia. p. 103. ISBN 9780888650566.

- ^ The Guardian:Cyclone Pam: more deaths and water shortages to follow storm, 15 March 2015

- ^ Siméoni, Patricia (2009). Atlas du Vanouatou (Vanuatu) (in French) (Première ed.). Port-Vila: Éditions Géo-consulte. p. 85. ISBN 978-2-9533362-0-7.

- ^ "Vete Manung Island, Vanuatu - John Seach". travel.vu. Vanuatu Travel. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ Siméoni 2009, p. 85.

- ^ Siméoni 2009, p. 88.

- ^ "Global Surface Summary of the Day - GSOD". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ Brookfield, H.C.; Hart, Doreen (1971). Melanesia. London: Methuen & Co Ltd. p. 30. ISBN 0416-70290-2.

- ^ Neef, Gerrit; Hendy, Chris (July 1988). "Late Pleistocene-Holocene Acceleration of Uplift Rate in Southwest Erromango Island, Southern Vanuatu, South Pacific: Relation to the Growth of the Vanuatuan Mid Sedimentary Basin". The Journal of Geology. 96 (4). The University of Chicago Press: 481–494. Bibcode:1988JG.....96..481N. doi:10.1086/629242. ISSN 1537-5269. JSTOR 30062162. S2CID 129780988.

- ^ Neef & Hendy 1988, p. 484

- ^ Bellon, Hervé; Marcelot, Gérard; Lefèvre, Christian; Maillet, Patrick (1984). "Le volcanisme de l'île d'Erromango (République de Vanuatu) : calendrier de l'activité (données 40K-40Ar)" [Volcanism on Erromango Island (Vanuatu): activity after 40K-40Ar]. Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences, Série II (in French). 299 (6). Académie des Sciences: 261. ISSN 0249-6305. Retrieved 2014-12-04.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Siméoni 2009, p. 85

- ^ "Traitor's Head". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ Vanuatu National Statistics Office (2009a). "2009 National Population and Housing Census Basic Tables Report Volume 1" (PDF). vnso.gov.vu. p. 168. Retrieved 2014-12-04.

- ^ Vanuatu National Statistics Office (2009b). "2009 Census Summary Release" (PDF). vnso.gov.vu/. Port Vila: Vanuatu National Statistics Office. p. 5. Retrieved 2014-12-09.

- ^ Vanuatu National Statistics Office 2009a, p. 13.

- ^ Crowley, Terry (1997). "What happened to Erromango's languages?". Journal of the Polynesian Society. 106: 33–64.

- ^ Lynch, John. 1983. The languages of Erromango. In John Lynch (ed.), Studies in the Languages of Erromango. Pacific Linguistics C-79. Canberra: Australian National University, pp.1-10.

- ^ Lynch, John. n.d. Utaha and Sorung: Two Dead Languages of Erromanga. Unpublished ms., found in Arthur Capell’s documents archived at PARADISEC.

- ^ Crowley 1997, pp. 33-34.

- ^ Crowley 1997, pp. 33-58.

- ^ Crowley 1997, pp. 38-60.

- ^ Crowley 1997, pp. 53-56.

- ^ Lynch, John. "The languages of Erromango". In John Lynch (ed.), Studies in the Languages of Erromango. Pacific Linguistics C-79. (Australian National University, 1983) and Tryon, Darrell. New Hebrides Languages: An Internal Classification. Pacific Linguistics C-50 (Australian National University, 1976), cited in Crowley, Terry. An Erromangan (Sye) Grammar. Oceanic Linguistics Special Publication No. 27. (University of Hawaii Press, 1998).

- ^ Vanuatu National Statistics Office 2009a, p. 13.

- ^ Vanuatu National Statistics Office 2009a, p. 101.

- ^ Vanuatu National Statistics Office 2009a, p. 97.

- ^ Vanuatu National Statistics Office 2009a, p. 99.

External links

- Conserving and managing biodiversity in the South Pacific, Kauri Forest Reserve, Erromango Island, Vanuatu 2015, Rudolf Hahn CTA FAO (youtube video)

- Erromango Cultural Association

- Languages of Erromango

- SIL Ethnologue – Sie (Sye) language

- Australian Museum – Singing Arrows of Erromango

- Radio Australia – Revived Erromango bark cloth painting heads to exhibition in Germany

- Erromango – TAFEA Tourism Council

- Erromango – Vanuatu Aelan Walkabaot

- Vanuatu Islands Travel Info – Erromango, bush walking, hiking & trekking

- Cruising and diving Erromango

- Highlights of tourism in Erromango island (youtube video)

- Radio New Zealand – Sandalwood on Erromango

- Avibase – checklist of birds of Erromango