Cingulate cortex

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2013) |

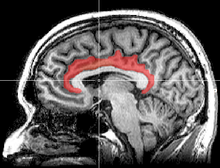

| Cingulate cortex | |

|---|---|

Medial surface of left cerebral hemisphere, with cingulate gyrus and cingulate sulcus highlighted. | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Cerebral cortex |

| Artery | Anterior cerebral |

| Vein | Superior sagittal sinus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Cortex cingularis, gyrus cinguli |

| Acronym(s) | Cg |

| MeSH | D006179 |

| NeuroNames | 159 |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_798 |

| TA98 | A14.1.09.231 |

| TA2 | 5513 |

| FMA | 62434 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

The cingulate cortex is a part of the brain situated in the medial aspect of the cerebral cortex. The cingulate cortex includes the entire cingulate gyrus, which lies immediately above the corpus callosum, and the continuation of this in the cingulate sulcus. The cingulate cortex is usually considered part of the limbic lobe.

It receives inputs from the thalamus and the neocortex, and projects to the entorhinal cortex via the cingulum. It is an integral part of the limbic system, which is involved with emotion formation and processing,[1] learning,[2] and memory.[3][4] The combination of these three functions makes the cingulate gyrus highly influential in linking motivational outcomes to behavior (e.g. a certain action induced a positive emotional response, which results in learning).[5] This role makes the cingulate cortex highly important in disorders such as depression[6] and schizophrenia.[7] It also plays a role in executive function and respiratory control.

Etymology

From Latin cingulātus (girdled)

Structure

Based on cerebral cytoarchitectonics it has been divided into the Brodmann areas 23, 24, 26, 29, 30, 31, 32 and 33. The areas 26, 29 and 30 are usually referred to as the retrosplenial areas.

Anterior cingulate cortex

This corresponds to areas 24, 32 and 33 of Brodmann and LA of Constantin von Economo and Bailey and von Bonin. It is continued anteriorly by the subgenual area (Brodmann area 25), located below the genu of the corpus callosum). It is cytoarchitectonically agranular. It has a gyral and a sulcal part. Anterior cingulate cortex can further be divided in the perigenual anterior cingulate cortex (near the genu) and midcingulate cortex. The anterior cingulate cortex receives primarily its afferent axons from the intralaminar and midline thalamic nuclei (see thalamus). The nucleus anterior receives mamillo-thalamic afferences. The mamillary neurons receive axons from the subiculum. The whole forms a neural circuit in the limbic system known as the Papez circuit.[8] The anterior cingulate cortex sends axons to the anterior nucleus and through the cingulum to other Broca's limbic areas. The ACC is involved in error and conflict detection processes.

Posterior cingulate cortex

This corresponds to areas 23 and 31 of Brodmann LP of von Economo and Bailey and von Bonin. Its cellular structure is granular. It is followed posteriorly by the retrosplenial cortex (area 29).[citation needed] Dorsally is the granular area 31. The posterior cingulate cortex receives a great part of its afferent axons from the superficial nucleus (or nucleus superior- falsely LD-[citation needed]) of the thalamus (see thalamus), which itself receives axons from the subiculum. To some extent it thus duplicates Papez' circuit. It receives also direct afferents from the subiculum of the hippocampus. Posterior cingulate cortex hypometabolism (with 18F-FDG PET) has been defined in Alzheimer's disease.

Inputs of the anterior cingulate gyrus

A retrograde tracing experiment on macaque monkeys revealed that the ventral anterior nucleus (VA) and the ventral lateral nucleus (VL) of the thalamus are connected with motor areas of the cingulate sulcus.[9] The retrosplenial region (Brodmann's area 26, 29 and 30) of cingulate gyrus can be divided into three parts: i.e., retrosplenial granular cortex A, retrosplenial granular cortex B and retrosplenial dysgranular cortex. The hippocampal formation sends dense projections to retrosplenial granular cortex A and B and fewer projections to the retrosplenial dysgranular cortex. The postsubiculum sends projections to retrosplenial granular cortex A and B and to the retrosplenial dysgranular cortex. The dorsal subiculum sends projections to retrosplenial granular cortex B, while ventral subiculum sends projections to retrosplenial granular cortex A. Entorhinal cortex – caudal parts – sends projections to the retrosplenial dysgranular cortex.[10]

Outputs of the anterior cingulate gyrus

The rostral cingulate gyrus (Brodmanns's area 32) projects to the rostral superior temporal gyrus, midorbitofrontal cortex and lateral prefrontal cortex.[11] The ventral anterior cingulate (Brodmann's area 24) sends projections to the anterior insular cortex, premotor cortex (Brodmann's area 6), Brodmann's area 8, the perirhinal area, the orbitofrontal cortex (Brodmann's area 12), the laterobasal nucleus of amygdala, and the rostral part of the inferior parietal lobule.[11] Injecting wheat germ agglutinin and horseradish peroxidase conjugate into the anterior cingulate gyrus of cats, revealed that the anterior cingulate gyrus has reciprocal connections with the rostral part of the thalamic posterior lateral nucleus and rostral end of the pulvinar.[12] The postsubiculum receives projections from the retrospleinal dysgranular cortex and the retrosplenial granular cortex A and B. The parasubiculum receives projections from the retrosplenial dysgranular cortex and retrosplenial granular cortex A. Caudal and lateral parts of the entorhinal cortex get projections from the retrosplenial dysgranular cortex, while the caudal medial entorhinal cortex receives projections from the retrosplenial granular cortex A. The retrosplenial dysgranular cortex sends projections to the perirhinal cortex. The retrospleinal granular cortex A sends projection to the rostral presubiculum.[10]

Outputs of the posterior cingulate gyrus

The posterior cingulate cortex (Brodmann's area 23) sends projections to dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Brodmann's area 9), anterior prefrontal cortex (Brodmann's area 10), orbitofrontal cortex (Brodmanns’ area 11), the parahippocampal gyrus, posterior part of the inferior parietal lobule, the presubiculum, the superior temporal sulcus and the retrosplenial region.[11] The retrosplenial cortex and caudal part of the cingulate cortex are connected with rostral prefrontal cortex via cingulate fascicule in macaque monkeys[13] Ventral posterior cingulate cortex was found to be reciprocally connected with the caudal part of the posterior parietal lobe in rhesus monkeys.[14] Also the medial posterior parietal cortex is connected with posterior ventral bank of the cingulate sulcus.[14]

Other connections

The anterior cingulate is connected to the posterior cingulate at least in rabbits. Posterior cingulate gyrus is connected with retrosplenial cortex and this connection is part of the dorsal splenium of the corpus callosum. The anterior and posterior cingulate gyrus and retrosplenial cortex send projections to subiculum and presubiculum.[15]

Clinical significance

Schizophrenia

Using a three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging procedure to measure the volume of the rostral anterior cingulate gyrus (perigenual cingulate gyrus), Takahashi et al. (2003) found that the rostral anterior cingulate gyrus is larger in control (healthy) females than males, but this sex difference was not found in people with schizophrenia. People with schizophrenia also had a smaller volume of perigenual cingulate gyrus than control subjects.[16]

Haznedar et al. (2004) studied metabolic rate of glucose in anterior and posterior cingulate gyrus in people with schizophrenia, schizotypal personality disorder (SPD) and compared them with a control group. The metabolic rate of glucose was found to be lower in the left anterior cingulate gyrus and the right posterior cingulate gyrus in people with schizophrenia relative to controls. Although people with SPD were expected to show a glucose metabolic rate somewhere between the individual with schizophrenia and controls, they actually had higher metabolic glucose rate in the left posterior cingulate gyrus. The volume of the left anterior cingulate gyrus was reduced in people with schizophrenia as compared with controls, but there was not any difference between people with SPD and people with schizophrenia. From these results it appears that the schizophrenia and SPD are two different disorders.[17]

A study of the volume of the gray and white matter in the anterior cingulate gyrus in people with schizophrenia and their healthy first and second degree relatives revealed no significant difference in the volume of the white matter in the people with schizophrenia and their healthy relatives. Nonetheless a significant difference in the volume of gray matter was detected, people with schizophrenia had smaller volume of gray matter than their second degree relatives, but not relative to their first degree relatives. Both the person with schizophrenia and their first degree healthy relatives have smaller gray matter volume than the second degree healthy relatives. It appears that genes are responsible for the decreased volume of gray matter in people with schizophrenia.[18]

Fujiwara et al. (2007) did an experiment in which they correlated the size of anterior cingulate gyrus in people with schizophrenia with their functioning on social cognition, psychopathology and emotions with control group. The smaller the size of anterior cingulate gyrus, the lower was the level of social functioning and the higher was the psychopathology in the people with schizophrenia. The anterior cingulate gyrus was found to be bilaterally smaller in people with schizophrenia as compared with control group. No difference in IQ tests and basic visuoperceptual ability with facial stimuli was found between people with schizophrenia and the control.[19]

Summary

People with schizophrenia have differences in the anterior cingulate gyrus when compared with controls. The anterior cingulate gyrus was found to be smaller in people with schizophrenia.[19] The volume of the gray matter in the anterior cingulate gyrus was found to be lower in people with schizophrenia.[17][18] Healthy females have larger rostral anterior cingulate gyrus than males, this sex difference in size is absent in people with schizophrenia.[16] The metabolic rate of glucose was lower in the left anterior cingulate gyrus and in the right posterior cingulate gyrus.[17]

In addition to changes in the cingulate cortex more brain structures show changes in people with schizophrenia as compared to controls. The hippocampus in people with schizophrenia was found to be smaller in size when compared with controls of the same age group,[20] and, similarly, the caudate and putamen were found to be smaller in volume in a longitudinal study of people with schizophrenia.[21] While the volume of gray matter is smaller, the size of the lateral and third ventricles is larger in people with schizophrenia.[22]

History

Cingulum means "belt" in Latin. The name was likely chosen because this cortex, in great part, surrounds the corpus callosum. The cingulate cortex is a part of the "grand lobe limbique" of Broca (1878) that consisted of a superior cingulate part (supracallosa) and an inferior hippocampic part (infracallosal).[23] The limbic lobe was separated from the remainder of the cortex by Broca for two reasons: first because it is not convoluted, and second because the gyri are directed parasagittally (contrary to the transverse gyrification). Since the parasagittal gyrification is observed in non-primate species, the limbic lobe was thus declared to be "bestial". As with other parts of the cortex, there have been and continue to be discrepancies concerning boundaries and naming. Brodmann (1909) further distinguished Areas 24 (anterior cingulate) and 23 (posterior) based on granularity. Most recently, it was included as a part of the limbic lobe in the Terminologia Anatomica (1998)[24] following von Economo's (1925) system.[25]

Additional images

-

Medial surface of cerebral hemisphere. Medial view. Deep dissection.

-

Medial surface of cerebral hemisphere. Medial view. Deep dissection.

-

Medial surface of cerebral hemisphere. Medial view. Deep dissection.

References

- ^ Hadland, K. A.; Rushworth M.F.; et al. (2003). "The effect of cingulate lesions on social behaviour and emotion". Neuropsychologia. 41 (8): 919–931. doi:10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00325-1. PMID 12667528.

- ^ "Cingulate binds learning". Trends Cogn Sci. 1 (1): 2. 1997. doi:10.1016/s1364-6613(97)85002-4. PMID 21223838.

- ^ Kozlovskiy, S.; Vartanov A.; Pyasik M.; Nikonova E.; Velichkovsky B. (10 October 2013). "Anatomical Characteristics of Cingulate Cortex and Neuropsychological Memory Tests Performance". Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 86: 128–133. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.08.537.

- ^ Kozlovskiy, S.A.; Vartanov A.V.; Nikonova E.Y.; Pyasik M.M.; Velichkovsky B.M. (2012). "The Cingulate Cortex and Human Memory Processes". Psychology in Russia: State of the Art. 5: 231–243. doi:10.11621/pir.2012.0014.

- ^ Hayden, B. Y.; Platt, M. L. (2010). "Neurons in Anterior Cingulate Cortex Multiplex Information about Reward and Action". Journal of Neuroscience. 30 (9): 3339–3346. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4874-09.2010. PMC 2847481. PMID 20203193.

- ^ Drevets, W. C.; Savitz, J.; Trimble, M. (2008). "The subgenual anterior cingulate cortex in mood disorders". CNS Spectrums. 13 (8): 663–681. doi:10.1017/s1092852900013754. PMC 2729429. PMID 18704022.

- ^ Adams, R.; David, A. S. (2007). "Patterns of anterior cingulate activation in schizophrenia: A selective review". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 3 (1): 87–101. doi:10.2147/nedt.2007.3.1.87. PMC 2654525. PMID 19300540.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Dorland's. Illustrated medical dictionary. Elsevier Saunders. p. 363. ISBN 978-14160-6257-8.

- ^ McFarland, N. R.; Haber, S. N. (2000). "Convergent Inputs from Thalamic Motor Nuclei and Frontal Cortical Areas to the Dorsal Striatum in the Primate". The Journal of Neuroscience. 20 (10): 3798–3813. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03798.2000.

- ^ a b Wyass, J. M.; Van Groen, T. (1992). "Connections between the retrosplenial cortex and the hippocampal formation in the rat: A review". Hippocampus. 2 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1002/hipo.450020102. PMID 1308170.

- ^ a b c Pandya, D. N.; Hoesen, G. W.; Mesulam, M. -M. (1981). "Efferent connections of the cingulate gyrus in the rhesus monkey". Experimental Brain Research. 42–42 (3–4): 319–330. doi:10.1007/BF00237497. PMID 6165607.

- ^ Fujii, M. (1983). "Fiber connections between the thalamic posterior lateral nucleus and the cingulate gyrus in the cat". Neuroscience Letters. 39 (2): 137–142. doi:10.1016/0304-3940(83)90066-6. PMID 6688863.

- ^ Petrides, M; Pandya, DN (Oct 24, 2007). "Efferent association pathways from the rostral prefrontal cortex in the macaque monkey". The Journal of Neuroscience. 27 (43): 11573–86. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2419-07.2007. PMC 6673207. PMID 17959800.

- ^ a b Cavada, C.; Goldman-Rakic, P. S. (1989). "Posterior parietal cortex in rhesus monkey: I. Parcellation of areas based on distinctive limbic and sensory corticocortical connections". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 287 (4): 393–421. doi:10.1002/cne.902870402. PMID 2477405.

- ^ Adey, W. R. (1951). "An Experimental Study of the Hippocampal Connexions of the Cingulate Cortex in the Rabbit". Brain. 74 (2): 233–247. doi:10.1093/brain/74.2.233. PMID 14858747.

- ^ a b Takahashi, T.; Suzuki, M.; Kawasaki, Y.; Hagino, H.; Yamashita, I.; Nohara, S.; Nakamura, K.; Seto, H.; Kurachi, M. (2003). "Perigenual cingulate gyrus volume in patients with schizophrenia: A magnetic resonance imaging study". Biological Psychiatry. 53 (7): 593–600. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01483-X. PMID 12679237.

- ^ a b c Haznedar, M. M.; Buchsbaum, M. S.; Hazlett, E. A.; Shihabuddin, L.; New, A.; Siever, L. J. (2004). "Cingulate gyrus volume and metabolism in the schizophrenia spectrum". Schizophrenia Research. 71 (2–3): 249–262. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2004.02.025. PMID 15474896.

- ^ a b Costain, G.; Ho, A.; Crawley, A. P.; Mikulis, D. J.; Brzustowicz, L. M.; Chow, E. W. C.; Bassett, A. S. (2010). "Reduced gray matter in the anterior cingulate gyrus in familial schizophrenia: A preliminary report". Schizophrenia Research. 122 (1–3): 81–84. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2010.06.014. PMC 3129334. PMID 20638248.

- ^ a b Fujiwara, H.; Hirao, K.; Namiki, C.; Yamada, M.; Shimizu, M.; Fukuyama, H.; Hayashi, T.; Murai, T. (2007). "Anterior cingulate pathology and social cognition in schizophrenia: A study of gray matter, white matter and sulcal morphometry" (PDF). NeuroImage. 36 (4): 1236–1245. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.03.068. hdl:2433/124279. PMID 17524666.

- ^ Koolschijn, P. C. D. M. P.; Van Haren, N. E. M.; Cahn, W.; Schnack, H. G.; Janssen, J.; Klumpers, F.; Hulshoff Pol, H. E.; Kahn, R. S. (2010). "Hippocampal Volume Change in Schizophrenia". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 71 (6): 737–744. doi:10.4088/JCP.08m04574yel. PMID 20492835.

- ^ Mitelman, S. A.; Canfield, E. L.; Chu, K. W.; Brickman, A. M.; Shihabuddin, L.; Hazlett, E. A.; Buchsbaum, M. S. (2009). "Poor outcome in chronic schizophrenia is associated with progressive loss of volume of the putamen". Schizophrenia Research. 113 (2–3): 241–245. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2009.06.022. PMC 2763420. PMID 19616411.

- ^ Kempton, M. J.; Stahl, D.; Williams, S. C. R.; Delisi, L. E. (2010). "Progressive lateral ventricular enlargement in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis of longitudinal MRI studies" (PDF). Schizophrenia Research. 120 (1–3): 54–62. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2010.03.036. PMID 20537866.

- ^ Broca, P (1878). "Anatomie comparee des circonvolutions cerebrales: Le grand lobe limbique et la scissure limbique dans la serie des mammifères". Revue d'Anthropologie. 1: 385–498

- ^ "Terminologica Anatomica". www.unifr.ch. Retrieved 2018-11-15.

- ^ Economo, C., Koskinas, G.N. (1925). Die Cytoarchitektonik der Hirnrinde des erwachsenen Menschen. Wien: Springer Verlag.