Copeland's method

| A joint Politics and Economics series |

| Social choice and electoral systems |

|---|

|

|

|

Copeland's method or Copeland's pairwise aggregation method is a Smith-efficient Condorcet method in which candidates are ordered by the number of pairwise victories, minus the number of pairwise defeats.[1] It was invented by Ramon Llull in his 1299 treatise Ars Electionis, but his form only counted pairwise victories and not defeats (which could lead to a different result in the case of a pairwise tie).[2] It is named after Arthur Herbert Copeland, who independently proposed it in a 1951 lecture.[3]

Proponents argue that this method is easily understood by the general populace, which is generally familiar with the sporting equivalent. In many round-robin tournaments, the winner is the competitor with the most victories. It is also easy to calculate.

When there is no Condorcet winner (i.e., when there are multiple members of the Smith set), this method often leads to ties. For example, if there is a three-candidate majority rule cycle, each candidate will have exactly one loss, and there will be an unresolved tie between the three.

Critics argue that it also puts too much emphasis on the quantity of pairwise victories and defeats rather than their magnitudes.[citation needed]

Examples of the Copeland Method

Example with Condorcet winner

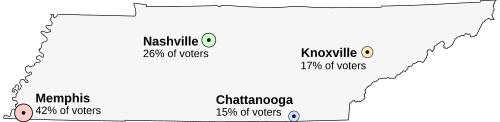

Suppose that Tennessee is holding an election on the location of its capital. The population is concentrated around four major cities. All voters want the capital to be as close to them as possible. The options are:

- Memphis, the largest city, but far from the others (42% of voters)

- Nashville, near the center of the state (26% of voters)

- Chattanooga, somewhat east (15% of voters)

- Knoxville, far to the northeast (17% of voters)

The preferences of each region's voters are:

| 42% of voters Far-West |

26% of voters Center |

15% of voters Center-East |

17% of voters Far-East |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

To find the Condorcet winner, every candidate must be matched against every other candidate in a series of imaginary one-on-one contests. In each pairing, each voter will choose the city physically closest to their location. In each pairing the winner is the candidate preferred by a majority of voters. When results for every possible pairing have been found they are as follows:

| Comparison | Result | Winner |

|---|---|---|

| Memphis vs Nashville | 42 v 58 | Nashville |

| Memphis vs Knoxville | 42 v 58 | Knoxville |

| Memphis vs Chattanooga | 42 v 58 | Chattanooga |

| Nashville vs Knoxville | 68 v 32 | Nashville |

| Nashville vs Chattanooga | 68 v 32 | Nashville |

| Knoxville vs Chattanooga | 17 v 83 | Chattanooga |

The wins and losses of each candidate sum as follows:

| Candidate | Wins | Losses | Net |

|---|---|---|---|

| Memphis | 0 | 3 | −3 |

| Nashville | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Knoxville | 1 | 2 | −1 |

| Chattanooga | 2 | 1 | 1 |

Nashville, with no defeats, is a Condorcet winner and, with the greatest number of net wins, is a Copeland winner.

Example without Condorcet winner

In an election with five candidates competing for one seat, the following votes were cast using a ranked voting method (100 votes with four distinct sets):

| 31: A > E > C > D > B | 30: B > A > E | 29: C > D > B | 10: D > A > E |

The results of the 10 possible pairwise comparisons between the candidates are as follows:

| Comparison | Result | Winner | Comparison | Result | Winner |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A v B | 41 v 59 | B | B v D | 30 v 70 | D |

| A v C | 71 v 29 | A | B v E | 59 v 41 | B |

| A v D | 61 v 39 | A | C v D | 60 v 10 | C |

| A v E | 71 v 0 | A | C v E | 29 v 71 | E |

| B v C | 30 v 60 | C | D v E | 39 v 61 | E |

The wins and losses of each candidate sum as follows:

| Candidate | Wins | Losses | Net |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| B | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| C | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| D | 1 | 3 | −2 |

| E | 2 | 2 | 0 |

No Condorcet winner (candidate who beats all other candidates in pairwise comparisons) exists. Candidate A is the Copeland winner, with the greatest number of wins minus losses.

As a Condorcet completion method, Copeland requires a Smith set containing at least five candidates to give a clear winner unless two or more candidates tie in pairwise comparisons.

Second-order Copeland method

The second-order Copeland method uses the sum of the Copeland scores of the defeated opponents as the means of determining a winner. This is useful in breaking ties when using the first-order Copeland method described above.

The second-order Copeland method has a particularly beneficial feature: manipulation of the voting is more difficult because it requires NP-complete complexity calculations to compute the manipulation.

External links

- Condorcet Class PHP library supporting multiple Condorcet methods, including Copeland method.

See also

References

- ^ Pomerol, Jean-Charles; Sergio Barba-Romero (2000). Multicriterion decision in management: principles and practice. Springer. p. 122. ISBN 0-7923-7756-7.

- ^ Colomer, Josep (2013). "Ramon Llull: From Ars Electionis to Social Choice Theory". Social Choice and Welfare. 40 (2): 317-328. doi:10.1007/s00355-011-0598-2. hdl:10261/125715.

- ^ Copeland, Arthur Herbert (1951), A 'reasonable' social welfare function, Seminar on Mathematics in Social Sciences, University of Michigan

Notes

- E Stensholt, "Nonmonotonicity in AV"; Voting matters; Issue 15, June 2002 (online).

- V.R. Merlin, and D.G. Saari, "Copeland Method. II. Manipulation, Monotonicity, and Paradoxes"; Journal of Economic Theory; Vol. 72, No. 1; January, 1997; 148–172.

- D.G. Saari. and V.R. Merlin, 'The Copeland Method. I. Relationships and the Dictionary'; Economic Theory; Vol. 8, No. l; June, 1996; 51–76.