Intracranial hemorrhage

| Intracranial hemorrhage | |

|---|---|

| |

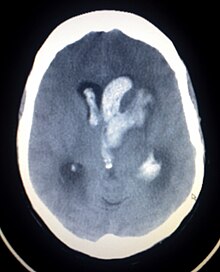

| Axial CT scan of a spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine |

| Complications | Coma |

Intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), also known as intracranial bleed, is bleeding within the skull.[1] Subtypes are intracerebral bleeds (intraventricular bleeds and intraparenchymal bleeds), subarachnoid bleeds, epidural bleeds, and subdural bleeds.[2]

Intracerebral bleeding affects 2.5 per 10,000 people each year.[1]

Signs and symptoms

Intracranial hemorrhage is a serious medical emergency because the buildup of blood within the skull can lead to increases in intracranial pressure, which can crush delicate brain tissue or limit its blood supply. Severe increases in intracranial pressure (ICP) can cause brain herniation, in which parts of the brain are squeezed past structures in the skull.

Causes

Intracranial bleeding occurs when a blood vessel within the skull is ruptured or leaks. It can result from physical trauma (as occurs in head injury) or nontraumatic causes (as occurs in hemorrhagic stroke) such as a ruptured aneurysm. Anticoagulant therapy, as well as disorders with blood clotting can heighten the risk that an intracranial hemorrhage will occur.[3]

More than half of all cases of intracranial hemorrhage is the result of hypertension.

Diagnosis

CT scan (computed tomography) is the definitive tool for accurate diagnosis of an intracranial hemorrhage.[citation needed] In difficult cases, a 3T-MRI scan can also be used.

When ICP is increased the heart rate may be decreased.

Classification

Types of intracranial hemorrhage are roughly grouped into intra-axial and extra-axial. The hemorrhage is considered a focal brain injury; that is, it occurs in a localized spot rather than causing diffuse damage over a wider area.

Intra-axial bleed

Intra-axial hemorrhage is bleeding within the brain itself, or cerebral hemorrhage. This category includes intraparenchymal hemorrhage, or bleeding within the brain tissue, and intraventricular hemorrhage, bleeding within the brain's ventricles (particularly of premature infants). Intra-axial hemorrhages are more dangerous and harder to treat than extra-axial bleeds.[4]

Extra-axial bleed

Extra-axial hemorrhage, bleeding that occurs within the skull but outside of the brain tissue, falls into three subtypes:

- Epidural hemorrhage (extradural hemorrhage) which occur between the dura mater (the outermost meninx) and the skull, is caused by trauma. It may result from laceration of an artery, most commonly the middle meningeal artery. This is a very dangerous type of injury because the bleed is from a high-pressure system and deadly increases in intracranial pressure can result rapidly. However, it is the least common type of meningeal bleeding and is seen in 1% to 3% cases of head injury.

- Patients have a loss of consciousness (LOC), then a lucid interval, then sudden deterioration (vomiting, restlessness, LOC)

- Head CT shows lenticular (convex) deformity.

- Subdural hemorrhage results from tearing of the bridging veins in the subdural space between the dura and arachnoid mater.

- Head CT shows crescent-shaped deformity

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), which occur between the arachnoid and pia meningeal layers, like intraparenchymal hemorrhage, can result either from trauma or from ruptures of aneurysms or arteriovenous malformations. Blood is seen layering into the brain along sulci and fissures, or filling subarachnoid cisterns (most often the chiasmatic cistern because of the presence of the anterior cerebral arteries of the circle of Willis and their branchpoints within that space). The classic presentation of subarachnoid hemorrhage is the sudden onset of a severe headache (a thunderclap headache). SAH is considered a form of stroke, despite technically being extra-axial. Confirmed spontaneous SAH requires further investigations as to the source of the bleeding, as the bleeding may recur without intervention.

Epidural hematoma

| Compared quality | Epidural | Subdural |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Between the skull and the inner meningeal layer of the dura mater or between outer endosteal and inner meningeal layer of dura mater | Between the meningeal layers of dura mater and the Arachnoid mater |

| Involved vessel | Temperoparietal locus (most likely) – Middle meningeal artery Frontal locus – anterior ethmoidal artery Occipital locus – transverse or sigmoid sinuses Vertex locus – superior sagittal sinus |

Bridging veins |

| Symptoms (depending on the severity)[5] | Lucid interval followed by unconsciousness | Gradually increasing headache and confusion |

| CT scan appearance | Biconvex lens | Crescent-shaped |

Epidural hematoma (EDH) is a rapidly accumulating hematoma between the dura mater and the cranium. These patients have a history of head trauma with loss of consciousness, then a lucid period, followed by loss of consciousness. Clinical onset occurs over minutes to hours. Many of these injuries are associated with lacerations of the middle meningeal artery. A "lenticular", or convex, lens-shaped extracerebral hemorrhage that does not cross suture lines will likely be visible on a CT scan of the head. Although death is a potential complication, the prognosis is good when this injury is recognized and treated.[citation needed]

Subdural hematoma

Subdural hematoma occurs when there is tearing of the bridging vein between the cerebral cortex and a draining venous sinus. At times they may be caused by arterial lacerations on the brain surface. Acute subdural hematoma are usually associated with cerebral cortex injury as well and hence the prognosis is not as good as extra dural hematoma. Clinical features depend on the site of injury and severity of injury. Patients may have a history of loss of consciousness but they recover and do not relapse. Clinical onset occurs over hours. A crescent shaped hemorrhage compressing the brain that does cross suture lines will be noted on CT of the head. Craniotomy and surgical evacuation is required if there is significant pressure effect on the brain.Complications include focal neurologic deficits depending on the site of hematoma and brain injury, increased intracranial pressure leading to herniation of brain and ischemia due to reduced blood supply and seizures.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage

A subarachnoid hemorrhage is bleeding into the subarachnoid space—the area between the arachnoid membrane and the pia mater surrounding the brain. Besides from head injury, it may occur spontaneously, usually from a ruptured cerebral aneurysm. Symptoms of SAH include a severe headache with a rapid onset (thunderclap headache), vomiting, confusion or a lowered level of consciousness, and sometimes seizures.[6] The diagnosis is generally confirmed with a CT scan of the head, or occasionally by lumbar puncture. Treatment is by prompt neurosurgery or radiologically guided interventions with medications and other treatments to help prevent recurrence of the bleeding and complications. Since the 1990s, many aneurysms are treated by a minimal invasive procedure known as endovascular coiling, which is carried out by instrumentation through large blood vessels. However, this procedure has higher recurrence rates than the more invasive craniotomy with clipping.[6]

Prognosis

It may be relatively safe to restart blood thinners after an ICH.[7]

References

- ^ a b Caceres, JA; Goldstein, JN (August 2012). "Intracranial hemorrhage". Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 30 (3): 771–94. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2012.06.003. PMC 3443867. PMID 22974648.

- ^ Naidich, Thomas P.; Castillo, Mauricio; Cha, Soonmee; Smirniotopoulos, James G. (2012). Imaging of the Brain, Expert Radiology Series,1: Imaging of the Brain. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 387. ISBN 978-1416050094.

- ^ Kushner D (1998). "Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: Toward Understanding Manifestations and Treatment". Archives of Internal Medicine. 158 (15): 1617–1624. doi:10.1001/archinte.158.15.1617. PMID 9701095. Archived from the original on 2008-05-14.

- ^ Seidenwurm DI (2007). "Introduction to brain imaging". In Brant WE, Helms CA (eds.). Fundamentals of Diagnostic Radiology. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-7817-6135-2. Retrieved 2008-11-17.

- ^ McDonough VT, King B. "What's the Difference Between a Subdural and Epidural Hematoma?" (PDF). BrainLine. WETA-TV. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 August 2010.

- ^ a b van Gijn J, Kerr RS, Rinkel GJ (2007). "Subarachnoid haemorrhage". Lancet. 369 (9558): 306–18. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60153-6. PMID 17258671.

- ^ Murthy, SB; Gupta, A; Merkler, AE; Navi, BB; Mandava, P; Iadecola, C; Sheth, KN; Hanley, DF; Ziai, WC; Kamel, H (June 2017). "Restarting Anticoagulant Therapy After Intracranial Hemorrhage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Stroke. 48 (6): 1594–1600. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.016327. PMC 5699447. PMID 28416626.

Further reading

- Shepherd S. 2004. "Head Trauma." Emedicine.com.

- Vinas FC and Pilitsis J. 2004. "Penetrating Head Trauma." Emedicine.com.

- Julian A. Mattiello, M.D.Michael Munz, M.D. 2001. "Four Types of Acute Post-Traumatic Intracranial Hemorrhage" The New England Journal of Medicine

External links

- ^ Capodanno, Davide (July 2018). "To unsubscribe, please click here". EuroIntervention. 14 (4): e367–e369. doi:10.4244/eijv14i4a63. ISSN 1969-6213. PMID 30028297.