GNU GRUB

GNU GRUB logo | |

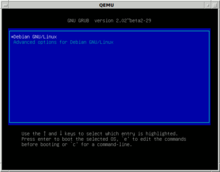

GRUB v2 running in text mode | |

| Original author(s) | Erich Boleyn |

|---|---|

| Developer(s) | GNU Project |

| Initial release | 1995 |

| Stable release | 2.04 (GRUB 2)

/ July 4, 2019[2] |

| Preview release | 2.04~rc1 (GRUB 2)[1]

/ April 9, 2019 |

| Repository | |

| Written in | Assembly, C[3] |

| Operating system | Linux, macOS, BSD, Solaris (x86 port), and Windows (through chainloading) |

| Platform | IA-32, x86-64, IA-64, ARM, PowerPC, s390x, MIPS and SPARC |

| Available in | English and others |

| Type | Bootloader |

| License | GPLv3[4] |

| Website | www |

GNU GRUB (short for GNU GRand Unified Bootloader, commonly referred to as GRUB) is a boot loader package from the GNU Project. GRUB is the reference implementation of the Free Software Foundation's Multiboot Specification, which provides a user the choice to boot one of multiple operating systems installed on a computer or select a specific kernel configuration available on a particular operating system's partitions.

GNU GRUB was developed from a package called the Grand Unified Bootloader (a play on Grand Unified Theory[5]). It is predominantly used for Unix-like systems. The GNU operating system uses GNU GRUB as its boot loader, as do most Linux distributions and the Solaris operating system on x86 systems, starting with the Solaris 10 1/06 release.

Operation

boot.img) can alternatively be written into one of the partition boot sectors.

Booting

When a computer is turned on, BIOS finds the configured primary bootable device (usually the computer's hard disk) and loads and executes the initial bootstrap program from the master boot record (MBR). The MBR is the first sector of the hard disk, with zero as its offset (sectors counting starts at zero). For a long time, the size of a sector has been 512 bytes, but since 2009 there are hard disks available with a sector size of 4096 bytes, called Advanced Format disks. As of October 2013[update], such hard disks are still accessed in 512-byte sectors, by utilizing the 512e emulation.[6]

The legacy MBR partition table supports a maximum of four partitions and occupies 64 bytes, combined. Together with the optional disk signature (four bytes) and disk timestamp (six bytes), this leaves between 434 and 446 bytes available for the machine code of a boot loader. Although such a small space can be sufficient for very simple boot loaders,[7] it is not big enough to contain a boot loader supporting complex and multiple file systems, menu-driven selection of boot choices, etc. Boot loaders with bigger footprints are thus split into pieces, where the smallest piece fits into and resides within the MBR, while larger piece(s) are stored in other locations (for example, into empty sectors between the MBR and the first partition) and invoked by the boot loader's MBR code.

Operating system kernel images are in most cases files residing on appropriate file systems, but the concept of a file system is unknown to the BIOS. Thus, in BIOS-based systems, the duty of a boot loader is to access the content of those files, so it can be loaded into the RAM and executed.

One possible approach for boot loaders to load kernel images is by directly accessing hard disk sectors without understanding the underlying file system. Usually, an additional level of indirection is required, in form of maps or map files – auxiliary files that contain a list of physical sectors occupied by kernel images. Such maps need to be updated each time a kernel image changes its physical location on disk, due to installing new kernel images, file system defragmentation etc. Also, in case of the maps changing their physical location, their locations need to be updated within the boot loader's MBR code, so the sectors indirection mechanism continues to work. This is not only cumbersome, but it also leaves the system in need of manual repairs in case something goes wrong during system updates.[8]

Another approach is to make a boot loader aware of the underlying file systems, so kernel images are configured and accessed using their actual file paths. That requires a boot loader to contain a driver for each of the supported file systems, so they can be understood and accessed by the boot loader itself. This approach eliminates the need for hardcoded locations of hard disk sectors and existence of map files, and does not require MBR updates after the kernel images are added or moved around. Configuration of a boot loader is stored in a regular file, which is also accessed in a file system-aware way to obtain boot configurations before the actual booting of any kernel images. As a result, the possibility for things to go wrong during various system updates is significantly reduced. As a downside, such boot loaders have increased internal complexity and even bigger footprints.[8]

GNU GRUB uses the second approach, by understanding the underlying file systems. The boot loader itself is split into multiple stages, allowing for itself to fit within the MBR boot scheme.

Two major versions of GRUB are in common use: GRUB version 1, called GRUB legacy, is only prevalent in older releases of Linux distributions, some of which are still in use and supported, for example CentOS 5. GRUB 2 was written from scratch and intended to replace its predecessor, and is now used by a majority of Linux distributions.

Version 0 (GRUB Legacy)

GRUB 0.x follows a two-stage approach. The master boot record (MBR) usually contains GRUB stage 1, or can contain a standard MBR implementation which chainloads GRUB stage 1 from the active partition's boot sector. Given the small size of a boot sector (512 bytes), stage 1 can do little more than load the next stage of GRUB by loading a few disk sectors from a fixed location near the start of the disk (within its first 1024 cylinders).

Stage 1 can load stage 2 directly, but it is normally set up to load the stage 1.5., located in the first 30 KiB of hard disk immediately following the MBR and before the first partition. In case this space is not available (unusual partition table, special disk drivers, GPT or LVM disk) the install of stage 1.5 will fail. The stage 1.5 image contains file system drivers, enabling it to directly load stage 2 from any known location in the filesystem, for example from /boot/grub. Stage 2 will then load the default configuration file and any other modules needed.

Version 2 (GRUB 2)

Startup on systems using BIOS firmware

- See illustration in last image on the right.

- 1st stage:

boot.imgis written to the first 440 bytes of the Master Boot Record (MBR in sector 0), or optionally in a partition's boot sector (PBR / VBR). It addressesdiskboot.imgby a 64-bit LBA address, thus it can load from above the 2 GiB limit of the MBR. The actual sector number is written bygrub-install. - 2nd stage:

diskboot.imgis the first sector ofcore.img(called stage 1.5 in GRUB Legacy) with the sole purpose to load the rest ofcore.imgidentified by LBA sector numbers also written bygrub-install. - On MBR partitioned disks:

core.imgis stored in the empty sectors (if available) between the MBR and the first partition. Recent operating systems suggest a 1 MiB gap here for alignment (2047*512 byte or 255*4KiB sectors). This gap used to be 62 sectors (31 KiB) as a reminder of the sector number limit of C/H/S addressing used by Bios before 1998, thereforecore.imgis designed to be smaller than 32 KiB. - On GPT partitioned disks: partitions are not limited to 4, thus

core.imgis written to its own tiny (1 MiB), filesystem-less BIOS boot partition. - 3rd stage:

core.imgenters 32-bit protected mode, uncompresses itself (the kernel of grub and filesystem modules to reach /boot/grub), then loads/boot/grub/<platform>/normal.modfrom the partition configured bygrub-install. If the partition index has changed, GRUB will be unable to find thenormal.mod, and presents the user with the GRUB Rescue prompt, where the user “can” find and loadnormal.mod, or the linux kernel. - The

/boot/grubdirectory can be located on any partition (GRUB can read many filesystems, including NTFS). Depending on how it was installed it's either in the root partition of the distribution, or a separate /boot partition. - 4th stage:

normal.mod(equivalent of stage 2 in GRUB Legacy) parses/boot/grub/grub.cfg, optionally loads modules (eg. for graphical UI) and shows the menu.

Startup on systems using UEFI firmware

- Common on motherboards since ca. 2012.

/efi/<distro>/grubx64.efiis installed as a file in the EFI System Partition, and booted by the firmware directly, without aboot.imgin sector 0./boot/grub/can be installed on the EFI System Partition as well.

After startup

GRUB presents a menu where the user can choose from operating systems (OS) found by grub-install. GRUB can be configured to automatically load a specified OS after a user-defined timeout. If the timeout is set to zero seconds, pressing and holding ⇧ Shift while the computer is booting makes it possible to access the boot menu.[9]

In the operating system selection menu GRUB accepts a couple of commands:

- By pressing e, it is possible to edit kernel parameters of the selected menu item before the operating system is started. The reason for doing this in GRUB (i.e. not editing the parameters in an already booted system) can be an emergency case: the system has failed to boot. Using the kernel parameters line it is possible, among other things, to specify a module to be disabled (blacklisted) for the kernel. This could be required if the specific kernel module is broken and thus prevents boot-up. For example, to blacklist the kernel module

nvidia-current, one could appendmodprobe.blacklist=nvidia-currentat the end of the kernel parameters. - By pressing c, the user enters the GRUB command line. The GRUB command line is not a regular Linux shell, like e.g. bash, and accepts only certain GRUB-specific commands, documented by various Linux distributions.[10]

Once boot options have been selected, GRUB loads the selected kernel into memory and passes control to the kernel. Alternatively, GRUB can pass control of the boot process to another boot loader, using chain loading. This is the method used to load operating systems that do not support the Multiboot Specification or are not supported directly by GRUB.

History

GRUB was initially developed by Erich Boleyn as part of work on booting the operating system GNU/Hurd, developed by the Free Software Foundation.[11] In 1999, Gordon Matzigkeit and Yoshinori K. Okuji made GRUB an official software package of the GNU Project and opened the development process to the public.[11] As of 2014[update], the majority of Linux distributions have adopted GNU GRUB 2, as well as other systems such as Sony's PlayStation 4.[12]

Development

GRUB version 1 (also known as "GRUB Legacy") is no longer under development and is being phased out.[13] The GNU GRUB developers have switched their focus to GRUB 2,[14] a complete rewrite with goals including making GNU GRUB cleaner, more robust, more portable and more powerful. GRUB 2 started under the name PUPA. PUPA was supported by the Information-technology Promotion Agency (IPA) in Japan. PUPA was integrated into GRUB 2 development around 2002, when GRUB version 0.9x was renamed GRUB Legacy.

Some of the goals of the GRUB 2 project include support for non-x86 platforms, internationalization and localization, non-ASCII characters, dynamic modules, memory management, a scripting mini-language, migrating platform specific (x86) code to platform specific modules, and an object-oriented framework. GNU GRUB version 2.00 was officially released on June 26, 2012.[15][16]

Three of the most widely used Linux distributions use GRUB 2 as their mainstream boot loader.[17][18][19] Ubuntu adopted it as the default boot loader in its 9.10 version of October 2009.[20] Fedora followed suit with Fedora 16 released in November 2011.[21] OpenSUSE adopted GRUB 2 as the default boot loader with its 12.2 release of September 2012.[22] Solaris also adopted GRUB 2 on the x86 platform in the Solaris 11.1 release.[23]

In late 2015, the exploit of pressing backspace 28 times to bypass the login password was found and quickly fixed.[24][25]

Variants

GNU GRUB is free and open-source software, so several variants have been created. Some notable ones, which have not been merged into GRUB mainline:

- OpenSolaris includes a modified GRUB Legacy that supports BSD disklabels, automatic 64-bit kernel selection, and booting from ZFS (with compression and multiple boot environments).[26][27]

- Google Summer of Code 2008 had a project to support GRUB legacy to boot from ext4 formatted partitions.[28]

- The Syllable project made a modified version of GRUB to load the system from its AtheOS File System.[29]

- TrustedGRUB extends GRUB by implementing verification of the system integrity and boot process security, using the Trusted Platform Module (TPM).[30]

- The Intel BIOS Implementation Test Suite (BITS) provides a GRUB environment for testing BIOSes and in particular their initialization of Intel processors, hardware, and technologies. BITS supports scripting via Python, and includes Python APIs to access various low-level functionality of the hardware platform, including ACPI, CPU and chipset registers, PCI, and PCI Express.[31]

- GRUB4DOS was a now-defunct GRUB legacy fork that improves the installation experience on DOS and Microsoft Windows by putting everything besides the GRLDR config in one image file. It can be loaded by the Windows Boot Manager.[32][33]

Utilities

GRUB configuration tools

The setup tools in use by various distributions often include modules to set up GRUB. For example, YaST2 on SUSE Linux and openSUSE distributions and Anaconda on Fedora/RHEL distributions. StartUp-Manager and GRUB Customizer are graphical configuration editors for Debian-based distributions. The development of StartUp-Manager stopped on 6 May 2011 after the lead developer cited personal reasons for not actively developing the program.[34] GRUB Customizer is also available for Arch-based distributions.

For GRUB 2 there are KDE Control Modules.[35][36]

GRLDR ICE is a tiny tool for modifying the default configuration of grldr file for GRUB4DOS.[37]

Boot repair utilities

Boot-Repair is a simple graphical tool for recovering from frequent boot-related problems with GRUB and Microsoft Windows bootloader. This application is available under GNU GPL license. Boot-Repair can repair GRUB on multiple Linux distributions including, but not limited to, Debian, Ubuntu, Mint, Fedora, openSUSE, and Arch Linux.

Installer for Windows

Grub2Win is a Windows open-source software package. It allows GNU GRUB to boot from a Windows directory. The setup program installs GNU GRUB version 2.04 to an NTFS partition. A Windows GUI application is then used to customize the GRUB boot menu, themes, UEFI boot order, scripts etc. All GNU GRUB scripts and commands are supported for both UEFI and legacy systems. Grub2Win can configure GRUB for multiboot of Windows, Ubuntu, openSuse, Fedora and many other Linux distributions. It is freely available under GNU GPL License at SourceForge.

Alternative boot-managers

The strength of GRUB is the wide range of supported platforms, file-systems, and operating systems, making it the default choice for distributions and embedded systems.

However, there are boot-managers targeted at the end user that gives more friendly user experience, graphical OS selector and simpler configuration:

- rEFInd – Macintosh-style graphical boot-manager, only for UEFI-based computers (BIOS not supported).

- CloverEFI – Macintosh-style graphical boot-manager for BIOS and UEFI-based computers. Emulates UEFI with a heavily modified DUET from the TianoCore project. Requires a FAT formatted partition even on BIOS systems. As a benefit, it has a basic filesystem driver in the partition boot sector, avoiding the brittleness of GRUB 2nd, 3rd stage and the infamous GRUB Rescue prompt. The user interface looks similar to rEFInd: both inherit from the abandoned boot-manager rEFIt.

Non-graphical alternatives:

- systemd-boot – Light, UEFI-only boot-manager with text-based OS selector menu.

External links

How-Tos and troubleshooting

Distribution wikis have many solutions for common issues and custom setups that might help you:

- Arch Linux /GRUB

- Ubuntu /Grub2 (also see Links at the bottom)

- Fedora /GRUB_2

- Gentoo /GRUB2

- Grub2 theme tutorial

Documentation

- GRUB manual – most detailed documentation, including all commands

- Official website

- GRUB wiki archived in 2010

Introductory articles

- Boot with GRUB, an April 2001 article in Linux Journal

Technicalities

- Booting Linux on x86 using Grub2 – in-depth article

- Unified Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI firmware, common since 2012)

- GUID Partition Table (GPT) – handles hard drives bigger than 2 TiB and more than 4 partitions

- Master boot record used with BIOS firmware (motherboards roughly before 2012)

- BIOS Boot Specification Version 1.01 (January 11, 1996) – hard to find

See also

- SysLinux (IsoLinux) – commonly used bootloader on CDs, DVDs

- NTLDR (BOOTMGR) – Windows bootloader

- Comparison of boot loaders

References

- ^ https://alpha.gnu.org/gnu/grub/

- ^ Kiper, Daniel (July 4, 2019). "GRUB 2.04 release". grub-devel (Mailing list). Retrieved July 5, 2019.

{{cite mailing list}}: Unknown parameter|mailinglist=ignored (|mailing-list=suggested) (help) - ^ "Ohloh Analysis Summary – GNU GRUB". Ohloh. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ "GNU GRUB license". Archived from the original on September 11, 2013.

- ^ EnterpriseLinux.com Definitions Definition of GRand Unified Bootloader

- ^ Smith, Ryan (December 18, 2009). "Western Digital's Advanced Format: The 4K Sector Transition Begins". AnandTech. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ^ "mbldr (Master Boot LoaDeR)". mbldr.sourceforge.net. 2009. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ^ a b "Booting and Boot Managers". SUSE. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ^ Hoffman, Chris (September 22, 2014). "How to Configure the GRUB2 Boot Loader's Settings". HowToGeek.com.

- ^ "GNU GRUB documentation".

- ^ a b GRUB Manual – 1.2 Grub History. Gnu.org (2012-06-23). Retrieved on 2012-12-01.

- ^ "PS4 runs Orbis OS, a modified version of FreeBSD that's similar to Linux". extremetech.com. June 24, 2013. Retrieved October 23, 2013.

- ^ GNU GRUB – GRUB Legacy. Gnu.org. Retrieved on 2012-12-01.

- ^ "GNU GRUB – GRUB 2". Archived from the original on June 7, 2008. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). - ^ Serbinenko, Vladimir (June 28, 2012). "GRUB 2.00 released". grub-devel (Mailing list). Retrieved December 1, 2012.

{{cite mailing list}}: Unknown parameter|mailinglist=ignored (|mailing-list=suggested) (help) - ^ Larabel, Michael. "GRUB 2.00 Boot-Loader Officially Released". Phoronix.com. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- ^ Haddon, Tom (January 26, 2012). "An Introduction to Ubuntu". WebJunction. Archived from the original on October 28, 2012. Retrieved September 21, 2012.

- ^ Janssen, Cory. "What is Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL)?". Technopedia. Retrieved September 21, 2012.

- ^ Varghese, Sam (September 20, 2012). "SUSE chief lists progress since privatisation". Retrieved September 21, 2012.

- ^ "9.10 Karmic GRUB version". Distrowatch.com. Retrieved July 8, 2012.

- ^ GRUB 2. FedoraProject. Retrieved on 2012-12-01.

- ^ openSUSE:Upcoming features – openSUSE Archived September 20, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. En.opensuse.org. Retrieved on 2012-12-01.

- ^ Solaris 11.1. Oracle Retrieved 2015-03-19.

- ^ Khandelwal, Swati (December 16, 2015). "You can Hack into a Linux Computer just by pressing 'Backspace' 28 times". thehackernews.com.

- ^ Marco and, Hector; Ripoll, Ismael (December 2015). "Back to 28: Grub2 Authentication 0-Day".

- ^ x86: Modifying Boot Behavior by Editing the GRUB Menu at Boot Time Archived July 19, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Modifying Solaris Boot Behavior on x86 Based Systems (Task Map) – System Administration Guide: Basic Administration

- ^ x86: Supported GRUB Implementations Archived October 21, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, (System Administration Guide: Basic Administration) – Sun Microsystems

- ^ Peng, Tao. "Grub4ext4". Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ^ 2.3 Why does Syllable have its own version of GRUB? Archived January 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Syllable Documentation

- ^ "TrustedGRUB project". sourceforge.net. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- ^ BIOS Implementation Test Suite, Official BITS website

- ^ "grub4dos". Google Site. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- ^ "GRUB for DOS Introduction". grub4dos.sourceforge.net. 2007. Archived from the original on June 2, 2008. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; April 7, 2019 suggested (help) - ^ "StartUp-Manager is dead : StartUp-Manager". launchpad.net. Retrieved April 9, 2017.

- ^ GRUB2 Bootloader Editor. Kde-apps.org (2012-06-18). Retrieved on 2012-12-01.

- ^ "Grub2 KCM". KDE-Apps.org. Retrieved January 27, 2011.

- ^ "Grub4dos tutorial". Narod.ru.