Mass in B minor structure

| 'Mass in B minor' | |

|---|---|

BWV 232 | |

| by J. S. Bach | |

Autograph of the title page of the first book, Missa | |

| Form | Missa solemnis |

| Related | Bach's Missa of 1733; several movements parodies of cantata movements |

| Text | Latin Mass |

| Composed | 1748? – 1749: Leipzig |

| Movements | 27 in 4 parts (12 + 9 + 1 + 5) |

| Vocal | |

| Instrumental |

|

The Mass in B minor is Johann Sebastian Bach's only setting of the complete Latin text of the Ordinarium missae.[1] Towards the end of his life, mainly in 1748 and 1749, he finished composing new sections and compiling it into a complex, unified structure.

Bach structured the work in four parts:[2]

- Missa

- Symbolum Nicenum

- Sanctus

- Osanna, Benedictus, Agnus Dei et Dona nobis pacem

The four sections of the manuscript are numbered, and Bach's usual closing formula (S.D.G = Soli Deo Gloria) is found at the end of the Dona nobis pacem.

Some parts of the mass were used in Latin even in Lutheran Leipzig, and Bach had composed them: five settings of the Missa, containing the Kyrie and the Gloria, and several additional individual settings of the Kyrie and the Sanctus. To achieve the Missa tota, a setting of the complete text of the mass, he combined his most elaborate Missa, the Missa in B minor, written in 1733 for the court in Dresden, and a Sanctus written for Christmas of 1724. He added a few new compositions, but mostly derived movements from cantata movements, in a technique known as parody.

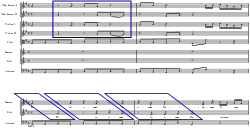

The Mass is a compendium of many different styles in vocal composition, in both the "stile antico" reminiscent of Renaissance music (even containing Gregorian chant) and the Baroque concertante style of his own time: fugal writing and dances, arias and a movement for two four-part choirs. Similar to architecture of the period, Bach achieved a symmetry of parts, with the profession of faith (Credo) in the center and the Crucifixus in its center. Bach scored the work for five vocal parts (two sopranos, alto, tenor and bass, SSATB). While some choral movements are for only four parts, the Sanctus is scored for six voices (SSAATB), and the Osanna even for two four-part choirs. Bach called for a rich instrumentation of brass, woodwinds and strings, assigning varied obbligato parts to different instruments.

History and parody

The Mass was Bach's last major artistic undertaking. The reason for the composition is unknown.[1] Scholars have found no plausible occasion for which the work may have been intended. Joshua Rifkin notes:

... likely, Bach sought to create a paradigmatic example of vocal composition while at the same time contributing to the venerable musical genre of the Mass, still the most demanding and prestigious apart from opera.[3]

Bach first composed a setting of the Kyrie and Gloria in 1733 for the Catholic royal court in Dresden. He presented that composition to Frederick Augustus II, Elector of Saxony (later, as Augustus III, also king of Poland),[1] accompanied by a letter:

In deepest Devotion I present to your Royal Highness this small product of that science which I have attained in Musique, with the most humble request that you will deign to regard it not according to the imperfection of its Composition, but with a most gracious eye ... and thus take me into your most mighty Protection.[4]

He arranged the text in diverse movements for a five-part choir and solo voices, according to the taste in Dresden where sacred music "borrowed" from Italian opera with a focus on choral movements, as musicologist Arthur Wenk notes.[5]

Bach expanded the Missa of 1733 to a Missa tota from 1748 to 1749, near the end of his life.[3][6][7] In these last years, he added three choral movements for the Credo: its opening Credo in unum Deum, Confiteor and Et incarnatus est. The Sanctus was originally an individual movement composed for Christmas 1724 in Leipzig.[1]

Most other movements of the mass are parodies of music from earlier cantatas,[7] dating back as far as 1714. Wenk points out that Bach often used parody to "bring a composition to a higher level of perfection".[8] The original musical sources of several movements are known, for others they are lost but the score shows that they are copied and reworked. Bach selected movements that carried a similar expression and affekt. For example, Gratias agimus tibi (We give you thanks) is based on Wir danken dir, Gott, wir danken dir[9] (We thank you, God, we thank you) and the Crucifixus (Crucified) is based on the general lamenting about the situation of the faithful Christian, Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen[9] (Weeping, lamenting, worrying, fearing) which Bach had composed already in 1714 as one of his first cantatas for the court of Weimar.

Bach quoted Gregorian chant twice, in the Credo in unum Deum as a theme and in the Confiteor as a cantus firmus embedded in complex polyphony.

Bach achieved a symmetry of the parts, with the profession of faith (Credo) in the center and the movement Crucifixus in its center. Markus Rathey, Associate Professor of Music History at the Institute of Sacred Music at the Yale School of Music, sees a similarity to architecture of the period, such as the Palace of Versailles. Bach knew buildings in that style, for example Schloss Friedrichsthal in Gotha, built in 1710.[10] Rathey continues:

The symmetry on earth mirrors the symmetric perfection of heaven. The purpose of art at this time—in architecture, the visual arts, and music—was not to create something entirely new, but to reflect this divine perfection, and in this way to praise God. We find such a symmetric outline in many pieces by Johann Sebastian Bach,19 but only in a few cases is this outline as consequent as in the B Minor Mass.[11]

The parts Kyrie, Gloria and Credo are all designed with choral sections as the outer movements, framing an intimate center of theological significance.

According to Christoph Wolff, the Mass can be seen as a "kind of specimen book of his finest compositions in every kind of style, from the stile antico of Palestrina in the 'Credo' and 'Confiteor' and the expressively free writing of the 'Crucifixus' and 'Agnus Dei', to the supreme counterpoint of the opening Kyrie as well as so many other choruses, right up to the most modern style in galant solos like 'Christe eleison' and 'Domine Deus'".[12] Bach made "a conscious effort to incorporate all styles that were available to him, to encompass all music history as far as it was accessible".[13] The Mass is a compendium of vocal sacred music, similar to other collections that Bach compiled during the last decade of his life, such as the Clavier-Übung III, The Art of Fugue, the Goldberg Variations, the Great Eighteen Chorale Preludes and The Musical Offering.[14]

Overview

Bach's autograph score of the Mass in B minor is subdivided in four sections. Part I is titled Missa, consisting of the same Kyrie and Gloria which constituted his Missa of 1733. The second part is titled Symbolum Nicenum (Latin for Nicene Creed, a.k.a. Credo). An early version of the first movement of this section is extant. The third section, called Sanctus, is based on an early version composed in 1724. The Hosanna and Benedictus, traditionally concluding the Sanctus, are however not included in this section, but open the next, which is called Osanna, Benedictus, Agnus Dei et Dona nobis pacem.[15]

Comparison of Bach's titles to the parts of the mass Five usual sections of the

Mass ordinaryMass in B minor sections Number of

movementsYear

fromYear

toI. Kyrie I. Missa (consisting of Kyrie

and Gloria)3 1733 1733 II. Gloria 9 ? 1733 III. Credo II. Symbolum Nicenum 9 1714 1749 IV. Sanctus

including Hosanna and BenedictusIII. Sanctus 2 1724 1724 IV. Osanna, Benedictus,

Agnus Dei et

Dona nobis pacem3 1732 1749 V. Agnus Dei

ending on "dona nobis pacem"2 1725 1749

Scoring

The work is scored for five vocal soloists, chorus and orchestra. Its movements are listed in a table with the scoring of voices and instruments, key, tempo marking, time signature and source. The movement numbering follows the Bärenreiter edition of the Neue Bach-Ausgabe, first in a consecutive numbering (NBA II), then in a numbering for the four individual parts (NBA I).

The voices are abbreviated S for soprano, A for alto, T for tenor, B for bass. Bach asked for two sopranos. Practical performances often have only one soprano soloist, sharing the parts for the second soprano (SII) between soprano and alto. A four-part choir is indicated by SATB, a five-part choir by SSATB. The Sanctus requires six vocal parts, SSAATB, which are often divided in the three upper voices versus the lower voices. The Osanna requires two choirs SATB.

Instruments in the orchestra are three trumpets (Tr), timpani (Ti), corno da caccia (Co), two flauti traversi (Ft), two oboes (Ob), two oboes d'amore (Oa), two bassoons (Fg), two violins (Vl), viola (Va), and basso continuo. The continuo is not mentioned in the table as it is present all the time. The other instruments are grouped by brass, woodwinds and strings.

Bach based movements of the Mass in B minor on earlier compositions. What is known about reworked earlier material is indicated in the last two columns of the table (earlier composition; year of composition), including some educated guesswork, as found in the indicated scholarly literature. This does not include the 1733 version of Part I (the movements that constitute the Kyrie and Gloria), but earlier compositions which Bach used as basis for that version.

Structure

| Movement | Instruments | Music | Origination | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NBA II | NBA I | Incipit | Solo | Choir | Brass | Wood | Strings | Key | Time | Tempo | Source[16] | Year |

I. Missa | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | Kyrie | SSATB | 2Ft 2Oa Fg | 2Vl Va | B minor | Adagio – Largo | Kyrie in G minor? | ||||

| 2 | 2 | Christe | S S | 2Vl | D major | likely | ||||||

| 3 | 3 | Kyrie | SATB | 2Ft 2Oa Fg | 2Vl Va | F♯ minor | ||||||

| 4a | 4 | Gloria | SSATB | 3Tr Ti | 2Ft 2Ob Fg | 2Vl Va | D major | 3 8 |

Vivace | likely | ||

| 4b | 5 | Et in terra pax | SSATB | 3Tr Ti | 2Ft 2Ob Fg | 2Vl Va | D major | likely | ||||

| 5 | 6 | Laudamus te | SII | 2Vl Va | A major | likely | ||||||

| 6 | 7 | Gratias agimus tibi | SATB | 3Tr Ti | 2Ft 2Ob Fg | 2Vl Va | D major | BWV 29/2 | 1731 | |||

| 7a | 8 | Domine Deus | S T | Ft | 2Vl Va | G major | BWV 193a/5? (music lost) | |||||

| 7b | 9 | Qui tollis | SATB | 2Ft | 2Vl Va Vc | F♯ minor | Lento | BWV 46 | 1723 | |||

| 8 | 10 | Qui sedes | A | Oa | 2Vl Va | B minor | 6 8 |

likely | ||||

| 9a | 11 | Quoniam tu solus sanctus | B | Co | 2Fg | D major | 3 4 |

likely | ||||

| 9b | 12 | Cum sancto spiritu | SSATB | 3Tr Ti | 2Ft 2Ob Fg | 2Vl Va | D major | 3 4 |

Vivace | |||

II. Symbolum Nicenum | ||||||||||||

| 10 | 1 | Credo in unum Deum | SSATB | 2Vl | D Major / A Mixolydian | Credo in G[15] | ||||||

| 11 | 2 | Patrem omnipotentem | SATB | 3Tr Ti | 2Ob | 2Vl Va | D major | lost, also source for BWV 171/1 | 1729 | |||

| 12 | 3 | Et in unum Dominum | S A | 2Oa | 2Vl Va | G major | Andante | lost, also source for BWV 213/11? | ||||

| 13 | 4 | Et incarnatus est | SSATB | 2Vl | B minor | 3 4 |

||||||

| 14 | 5 | Crucifixus | SATB | 2Ft | 2Vl Va | E minor | 3 2 |

BWV 12/2 | 1714 | |||

| 15 | 6 | Et resurrexit | SSATB | 3Tr Ti | 2Ft 2Ob | 2Vl Va | D major | 3 4 |

BWV Anh. 9/1? | |||

| 16 | 7 | Et in Spiritum Sanctum | B | 2Oa | A major | 6 8 |

likely | |||||

| 17a | 8 | Confiteor | SSATB | F♯ minor | ||||||||

| 17b | Et expecto | SSATB | F♯ minor | Adagio | ||||||||

| 9 | Et expecto | SSATB | 3Tr Ti | 2Ft 2Ob | 2Vl Va | D major | Vivace e Allegro | BWV 120/2 | ||||

III. Sanctus | ||||||||||||

| 18a | Sanctus | SSA ATB | 3Tr Ti | 3Ob | 2Vl Va | D major | Sanctus | 1724 | ||||

| 18b | Pleni sunt coeli | SSAATB | 3Tr Ti | 3Ob | 2Vl Va | D major | 3 8 |

|||||

IV. Osanna, Benedictus, Agnus Dei et Dona nobis pacem | ||||||||||||

| 19 | 1 | Osanna in excelsis | SATB SATB | Tr Ti | 2Ft 2Ob | 2Vl Va | D major | 3 8 |

BWV Anh. 11/1? (→ BWV 215) | 1732 | ||

| 20 | 2 | Benedictus | T | Ft | B minor | 3 4 |

likely | |||||

| 21 | 3 | Osanna (repetatur) | ||||||||||

| 22 | 4 | Agnus Dei | A | 2Vl | G minor | BWV Anh. 196/3? | 1725 | |||||

| 23 | 5 | Dona nobis pacem | SATB | 3Tr Ti | 2Ft 2Ob | 2Vl Va | D major | BWV 29/2 as Gratias | 1731 | |||

Parts and movements

No. 1 Missa

Kyrie and Gloria

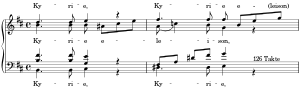

The section Kyrie is structured, following tradition, in a threefold acclamation of God, a chorus for the Kyrie I, a duet Christe, and a different chorus for Kyrie II. Kyrie I is in B minor, Christe in D major, Kyrie II in F-sharp minor. The three notes B, D and F-sharp form the B minor triad. Butt notes D major as the central key, corresponding to the "atonement of Christ".[17]

The Gloria is structured in symmetry as a sequence of choral movements and solo movements, arias and a central duet, in three sections. The first is opened with a chorus followed by an aria, closed in the last section in symmetry by an aria followed with a chorus; the middle section alternates choral music with solo movements.[18] The trumpets are introduced as a symbol of divine glory in several movements, beginning and ending in D major, with a planned architecture of keys in the middle movements. The central duet is in the "lowly" key of G major, referring to Christ as a "human incarnation of God".[17] A corno da caccia appears only once in the whole work, in the movement Quoniam, which is about the holiness of God.

Kyrie I

The first movement is scored for five-part choir, woodwinds and strings. As the Dresden Mass style required, it opens with a short homophonic section,[19] followed by an extended fugue in two sections, which both begin with an instrumental fugue.[20]

Christoph Wolff notes a similarity between the fugue theme and one by Johann Hugo von Wilderer, whose mass Bach had probably copied and performed in Leipzig before 1731. Wilderer's mass also has a slow introduction, a duet as the second movement and a motet in stile antico, similar to late Renaissance music,[4] as the third movement.[21] Bach based the work on a composition in C minor, as mistakes in the copying process show.[21]

The vast movement has aspects of both a fugue and a ritornello movement.[22] In the first fugal section, the voices enter in the sequence tenor, alto, soprano I, soprano II, bass, expanding from middle range to the extreme parts, just as the theme expands from the repeated first notes to sighing motives leading upwards. In the second fugal section, the instruments begin in low registers, and the voices build, with every part first in extremely low range, from bass to soprano I. In both sections, the instruments open the fugue, but play with the voices once they enter.[18]

Christe

The acclamation of Christ stresses the second person of the Trinity and is therefore rendered as a duet of the two sopranos.[23] Their lines are often parallel, in an analogy to Christ and God proclaimed as "two in one". Probably a parody of an earlier work, it is Bach's only extant duet for two sopranos, stressing that idea.[24] Rathey points out that the duet is similar in many aspects to the love duets of Neapolitan opera.[25] Typical features of these duets are consonant melodies, in parallel thirds and sixths, or imitating each other, with sigh motifs as on the word Christe.[26] Rendering Christe eleison as a duet follows the Dresden Mass style.[19]

Kyrie II

The second acclamation of God is a four-part choral fugue, set in stile antico, with the instruments playing colla parte.[23] This style was preferred at the court in Dresden.[11] The theme begins with intervals such as minor seconds and major seconds, similar to the motif B-A-C-H. The first entrances build from the lowest voice in the sequence bass, tenor, alto, soprano.[27] According to Christoph Wolff, Bach assimilated the stricter style of the Renaissance only in the early 1730s, after he had composed most of his cantatas, and this movement is his first "significant product" in the style.[13]

Gloria

The Gloria is structured in nine movements. The first and last are similar in style, concertante music of the eighteenth century.[28] In further symmetry, the opening in two different tempos corresponds to the final sequence of an aria leading to "Cum sancto spiritu", the soprano II solo with obbligato violin "Laudamus te" to the alto solo with obbligato oboe "Qui sedes", and the choral movements "Gratias" frame the central duet of soprano I and tenor "Domine Deus".[17]

The text of the Hymnus Gloria begins with the angels' song from Luke's Christmas story. Bach used this section, the central duet and the concluding doxology as a Christmas cantata, Gloria in excelsis Deo, BWV 191 (Glory to God in the Highest), probably in 1745, a few years before the compilation of the Mass. The opening is set as a five-part chorus, beginning with an instrumental presentation of the material.[28] In great contrast to the first section Kyrie, it is in D major, introducing the trumpets and timpani.[29] The first thought, "Gloria in excelsis Deo" (Glory to God in the Highest), is set in 3/8 time, compared by Wenk to the Giga, a dance form.[30]

Et in terra pax

The continuation of the thought within the angels' song, "Et in terra pax" (and peace on earth), is in common time. The duration of an eighth note stays the same, Bach thus achieves a contrast of "heavenly" three eights, a symbol of the Trinity, and "earthly" four quarters.[31] The voices start this section,[28] and the trumpets are silent for its beginning, but return for its conclusion.[32]

Laudamus te

An aria for soprano II and obbligato violin express the praise and adoration of God in vivid coloraturas.[33] It has been argued that Bach might have thought of the Dresden taste and the specific voice of Faustina Bordoni.[28]

Gratias agimus tibi

A four-part chorus in stile antico illustrates the idea of thanks and praise, again with trumpets and timpani. It is based on the first choral movement of Wir danken dir, Gott, wir danken dir, BWV 29,[9] which also expresses the idea of thanks to God and praise of his creation (but this cantata movement may have been derived from an even earlier source[34]). The first part of the text, devoted to thanks, is a melody in even tempo that rises gradually and falls again. The voices enter without instrumental support in dense succession. The countersubject on the second line "propter magnam gloriam tuam" (for your great glory), devoted to the glory of God, is more complex in rhythm. Similarly, in the cantata the second line "und verkündigen deine Wunder" (and proclaim your wonders) leads to a more vivid countersubject.[35] Towards the end of the movement, the trumpets take part in the polyphony of the dense movement.[36]

Domine Deus

The section addressing God as Father and Son is again a duet, this time of soprano I and tenor. The voices are often in canon and in parallel, as in the Christe.[37] The movement is likely another parody, possibly from the 1729 cantata Ihr Häuser des Himmels, BWV 193a. As the Christe, it is a love-duet addressing Jesus. Both duets appear as the center of the symmetry within the respective part, Kyrie and Gloria. Here an obbligato flute opens a concerto with the orchestra and introduces material that the voices pick up.[38]

Rathey points out, that the scoring at first glance does not seem to match the text "Domine Deus, Rex coelestis" (Lord God, Heavenly King), but it matches the continuation "Domine Deus, Agnus Dei" (Lord God, Lamb of God), stressing the Lutheran "theologia crucis" (theology of the cross) that the omnipotent God is the same as the one revealed on the cross.[39]

Qui tollis

When the text reaches the phase "Qui tollis peccata mundi" (who takest away the sins of the world), the music is given attacca to a four-part choir with two obbligato flutes.[40] The movement is based on the first choral movement of Schauet doch und sehet, ob irgend ein Schmerz sei, BWV 46.[9] The cantata text was based on the Book of Lamentations, Lamentations 1:12, a similar expression of grief.[39] Bach changed the key and the rhythm because of the different text.[9] The key of B minor connects this description of "Christ's suffering and mankind's plea for mercy" to the similar quest in the first Kyrie. The keys G – B – D form the G major triad, leading to the "home key" of the Gloria, D major.[17] Bach uses only part of the cantata movement, without the instrumental introduction and the second part.[41]

Qui sedes

The continuation of the thought, "Qui sedes ad dexteram Patris" (who sits at the right [hand] of the Father), is expressed by an aria for alto and obbligato oboe d'amore.[42][29] It is probably a parody. In Bach's earlier settings of the mass he had treated "Qui tollis and "Qui sedes" as one movement, here he distinguished Jesus at the right hand of the father by dance-like music.[39] Wenk likens it to a gigue.[30]

Quoniam tu solus sanctus

The last section begins with an aria for bass, showing "Quoniam tu solus sanctus" (For you alone are holy) in an unusual scoring of only corno da caccia and two bassoons.[29] Paczkowski points out the symbolic function of this corno da caccia as well as the polonaise.[43] By using the polonaise, Bach not only expressed the text by musical means, but also paid respect to the King of Poland and Elector of Saxony, August III, to whom the Mass is dedicated. Probably a parody, it is the only movement in the work using the horn.[44][45] The unusual scoring provides a "solemn character".[46] Butt observes that Bach uses a rhythmic pattern throughout the movement in the two bassoons which is even extended into the following movement, although they originally were independent. The repeated figure of an anapaest provides the "rhythmic energy of the texture."[47]

Cum sancto spiritu

On the continuing text "Cum sancto spiritu" (with the Holy Spirit), the choir enters in five parts, in symmetry to the beginning. A homophonic section is followed by a fugue.[48][29] The concertante music corresponds in symmetry to the opening of the Gloria, both praising God.[46]

No. 2 Symbolum Nicenum

The text of the profession of faith, Credo, is the Nicene Creed. It is structured in three sections, regarding Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Bach follows the structure, devoting two choral movements to the first section, beginning the second section with a duet, followed by three choral movements, and opening the third with an aria, followed by two choral movements. The center is the Crucifixus, set in E minor, the lowest key of the part. The Crucifixus is also the oldest music in the Mass, dating back to 1714.[18] The part begins and ends with a sequence of two connected choral movements in contrasting style, a motet in stile antico, containing a chant melody, and a concerto. The chant melodies are devoted to two of the key words of this part: Credo (I believe) and Confiteor (I confess).[49]

Credo in unum Deum

The Credo begins with "Credo in unum Deum" (I believe in one God), a polyphonic movement for five-part choir, to which two obbligato violins add independent parts. The theme is a Gregorian Chant,[50] first presented by the tenor in long notes on a walking bass of the continuo. The other voices enter in the sequence bass, alto, soprano I, soprano II, each one before the former one even finishes its line. The two violins enter independently, reaching a seven-part fugue.[51] The complex counterpoint of the seven parts, five voices and two violins, expands the theme of the chant, often in stretto function, and uses a variety of countersubjects. In the second exposition (sequence of fugue entries), the bass voice is missing, leading to anticipation and a climactic entry in augmentation (long notes) beginning the third exposition, just as an entry of the first violin ends the second exposition. Musicologist John Butt summarizes: "By using numerous stile antico devices in a particular order and combination, Bach has created a movement in which a standardised structure breeds a new momentum of its own".[52]

This movement in stile antico contrasts with the following modern concerto-style movement, Patrem omnipotentem. This contrast is reminiscent of the contrast between the two Kyrie movements and foreshadows the last two movements of the Symbolum Nicenum. Recent research dates the movement to 1747 or 1748 and suggests that it might have been the introduction to a Credo by a different composer, before Bach began to assemble the Mass.[53]

Patrem omnipotentem

The thought is continued in "Patrem omnipotentem" (to the Father, almighty), in a four-part choral movement with trumpets.[54] The movement probably shares its original source with the opening chorus of Gott, wie dein Name, so ist auch dein Ruhm, BWV 171 (God, as Your name is, so is also Your praise),[9] which also expresses the idea of thanks to God and praise of his creation.[49] The voices sing a fugue to a concerto of the orchestra. The bass introduces the theme, without an instrumental opening, while the other voices repeat simultaneously in homophony "Credo in unum Deum" as a firm statement. The theme contains all eight notes of the scale, as a symbol completeness.[18] Bach noted at the end of the movement that it contains 84 measures, the multiplication of 7 and 12, a hint at the symbolic meaning of numbers. The word "Credo" appears 49 times (7*7), the words "Patrem omnipotentem" 84 times.

Et in unum Dominum

The belief in Jesus Christ begins with "Et in unum Dominum" (And in one Lord), another duet, this time of soprano and alto, beginning in a canon where the second voice follows the first after only one beat. The instruments often play the same line with different articulation.[55] The movement is based on a lost duet which served already in 1733 as the basis for a movement of Laßt uns sorgen, laßt uns wachen, BWV 213. Bach headed the movement "Duo voces articuli 2" which can be translated as "Two voices express 2" or "the two vocal parts of Article 2". The text included originally the line "Et incarnatus est de Spiritu sancto ex Maria virgine et homo factus est", illustrating "descendit" by a descending figure for the violins. When Bach treated "Et incarnatus est" as a separate choral movement, he rearranged the text, and the figure lost its "pictorial association".[56]

Et incarnatus est

The virgin birth, "Et incarnatus est" (And was incarnate), is a five-part movement. It is probably Bach's last vocal composition, dating from the end of 1749 or the first weeks of 1750.[57] Until then, the text had been included in the preceding duet. The late separate setting of the words which had been given special attention by previous composers of the mass, established the symmetry of the Credo. The humiliation of God, born as man, is illustrated by the violins in a pattern of one measure that descends and then combines the symbol of the cross and sighing motifs, alluding to the crucifixion. The voices sing a motif of descending triads. They enter in imitation starting in measure 4, one voice every measure in the sequence alto, soprano II, soprano I, tenor, bass, forming a rich texture. The text "ex Maria vergine" (out of the virgin Mary) appears in an upward movement, "et homo factus est" (and made man) is even in upward triads.[58]

Crucifixus

"Crucifixus" (Crucified), the center of the Credo part, is the oldest music in the setting of the Mass, dating back to 1714. It is a passacaglia, with the chromatic fourth in the bass line repeated thirteen times.[59] Wenk likens it to a sarabande.[30] The movement is based on the first section of the first choral movement of Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen, BWV 12.[9] Bach transposed the music from F minor to E minor, changed the instrumentation and repeated each bass note for more expressiveness.[57] Bach begins the movement with an instrumental setting of the bass line, while the cantata movement started immediately with the voices.[60]

The suffering of Jesus is expressed in chromatic melodic lines, dissonant harmonies, and sigh-motifs.[49] The final line, on the 13th repeat of the bass line, "et sepultus est" (and was buried) was newly composed, with the accompaniment silent and a modulation to G major, to lead to the following movement.[57] At the end, soprano and alto reach the lowest range of the movement on the final "et sepultus est" (and was buried).[60] A pianissimo ending of this movement, contrasted by a forte Et resurrexit, follows the Dresden Mass style.[19]

Et resurrexit

"Et resurrexit" (And is risen) is expressed by a five-part choral movement with trumpets.[61] The concerto on ascending motifs[49] renders the resurrection, the ascension and the second coming, all separated by long instrumental interludes and followed by a postlude. "Et iterum venturus est" (and will come again) is given to the bass only, for Bach the vox Christi (voice of Christ).[61] Wenk likens the movement to a Réjouissance dance, a "light festive movement in triple meter, upbeat three eighth notes".[30]

Et in Spiritum Sanctum

A bass aria renders "Et in Spiritum Sanctum" (And in the Holy Spirit) with two obbligato oboes d'amore.[62] Only wind instruments are used to convey the idea of the Spirit as breath and wind. Speaking about the third person of the Trinity, the number three appears in many aspects: the aria is in three sections, in a triple 6/8-time, in A major, a key with three sharps, in German "Kreuz" (cross). A major is the dominant key to D major, the main key of the part, symbolising superiority, in contrast to the E minor of the "Crucifixus" as the lowest point of the architecture. The two oboes d'amore open the movement with a ritornello, with an ondulating theme played in parallels, which is later picked up by the voice. The ritornello is played between the three sections, the second time shortened, and it concludes the movement. The sections cover first the Holy Spirit, then his adoration with the Father and the Son, finally how he acted through the prophets and the church. The voice sings in highest register for the words "Et unam sanctam catholicam ... ecclesiam" (and one holy universal ... church), and expands in a repeat of the text in long coloraturas the words "catholicam" and "ecclesiam".[63] Wenk likens the movement to a Pastorale, a "Christmas dance", often on a drone bass.[30]

Confiteor

The belief in the baptism for the forgiveness of sins, "Confiteor" (I confess), is expressed in strict counterpoint, which incorporates a cantus firmus in plainchant.[64] The five-part choir is accompanied only by the continuo as a walking bass. The voices first perform a double fugue in stile antico, the first entries of the first theme, "Confiteor unum baptisma" (I proclaim the one baptism), from soprano to bass, followed by the first entries of the second theme, "in remissionem peccatorum" (for the remission of sinners), in the sequence tenor, alto, soprano I, soprano II, bass. The voices follow each other in fast succession, only one or two measures apart. The two themes appear in complex combinations, until the cantus firmus is heard from measure 73 as a canon in the bass and alto, and then in augmentation (long notes) from measure 92 in the tenor. [29] Then the movement slows down to Adagio (a written tempo change, rare in Bach), as the altos sing the word "peccatorum" (sinners) one last time in an extremely low range. As the text turns to the words "Et expecto resurrectionem mortuorum" (and expect the resurrection of the dead), the slow music modulates daringly with enharmonic transformations through several keys,[65] touching E-flat major and G-sharp major, vividly bringing a sense of dissolving into disorder as well as expectation before the resurrection to come. Whenever the word "mortuorum" appears, the voices sing long low notes, whereas "resurrectionem" is illustrated in triad motifs leading upwards.[66]

Et expecto

The expectation of a world to come, "Et expecto" (And I expect) is a joyful concerto of five voices with trumpets.[18] Marked "Vivace a Allegro", the voices begin with a trumpet fanfare in imitation on the same text as before. The movement is based on a choral movement dating from about 1729 which is used in Gott, man lobet dich in der Stille, BWV 120 and a related wedding cantata BWV 120a. In BWV 120 it sets the words Jauchzet, ihr erfreuten Stimmen (Exult, you delighted voices).[9] After this statement, which ends in homophony, the instruments begin a short section in which runs in rising sequences alternate with the fanfare, in which the voices are later embedded. The word "resurrectionem" appears then in the runs in the voices, one after the other in cumulation. A second repetition of instruments, embedded voices and upward runs brings the whole section to a jubilant close on the words "et vitam venturi saeculi. Amen" (and the life of the world to come. Amen), with extended runs on "Amen".[67] Wenk likens the movement to a bourrée, a dance in "quick duple meter with an upbeat".[30]

No. 3 Sanctus

Sanctus

Sanctus (Holy) is an independent movement written for Christmas 1724, scored for six voices SSAATB and a festive orchestra with trumpets and three oboes.[29][68] In the original, Bach had asked for three soprano parts, alto, tenor and bass. Only the score and duplicate parts of this performance survived.[1] The music in D major is in common time, but dominated by triplets. The three upper voices sing frequently alternating with the three lower voices, reminiscent of a passage by Isaiah about the angels singing "Holy, holy, holy" to each other (Isaiah 6:23). The number of voices may relate to the six wings of the seraphim described in that passage.[69]

Pleni sunt coeli

The continuation, "Pleni sunt coeli" (Full are the heavens), follows immediately, written for the same scoring, as a fugue in dancing 3/8 time with "quick runs".[70][29]

No. 4 Osanna, Benedictus, Agnus Dei et Dona nobis pacem

Osanna in excelsis

Osanna in excelsis (Osanna in the Highest) is set for two choirs and a festive orchestra, in the same key and time as the previous movement.[71][29] The movement is based, as is the opening chorus of the secular cantata Preise dein Glücke, gesegnetes Sachsen, BWV 215,[9] probably on the opening movement of the secular cantata Es lebe der König, der Vater im Lande, BWV Anh 11, of 1732.[72] The movement contrasts homophonic sections with fugal development.[73] Wenk likens the movement to the Passepied, a dance in "fast triple meter with an upbeat".[30]

Benedictus

The following thought, Benedictus, "blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord", is sung by the tenor in an aria with an obbligato instrument, probably a flauto traverso,[29] leading to a repeat of the Osanna.[74] The intimate music contrasts with the Osanna like the Christe eleison with Kyrie eleison. It is written in the latest Empfindsamer Stil (sensitive style) as if Bach had wanted to "prove his command of this style".[69]

Agnus Dei

Agnus Dei (Lamb of God) is sung by the alto with obbligato violins in unison.[75][29] The source for the aria is possibly the aria Entfernet euch, ihr kalten Hertzen (Leave, you cold hearts), the third movement of the lost wedding cantata Auf, süß entzückende Gewalt, BWV Anh 196.[76] It was the basis also for the fourth movement of the Ascension Oratorio, Lobet Gott in seinen Reichen, BWV 11, the aria Ach, bleibe doch, mein liebstes Leben.[69]

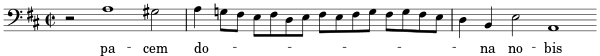

Dona nobis pacem

The final movement, Dona nobis pacem (Give us peace), recalls the music of thanks expressed in Gratias agimus tibi.[29][77] This concluding choral movement in Renaissance style follows the Dresden Mass style.[19] As the Gratias agimus tibi, the movement is based on the first choral movement of Wir danken dir, Gott, wir danken dir, BWV 29,[9] with minor alterations because of the different text. The text appears on both the theme and the countersubject, here stressing "pacem" (peace) at the beginning of the line.[18] By quoting Gratias, Bach connects asking for peace to thanks and praise to God. He also connects the Missa composed in 1733 to the later parts.[78]

References

- ^ a b c d e Wolf (2011).

- ^ J.S. Bach Mass in B Minor (1996).

- ^ a b Rifkin (2006).

- ^ a b Talbeck (2002).

- ^ Wenk (2011), p. 4.

- ^ Sherman (2004).

- ^ a b Libbey (2009).

- ^ Wenk (2011), p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Pérez Torres (2005), p. 5.

- ^ Rathey (2003), pp. 2–4.

- ^ a b Rathey (2003), p. 4.

- ^ Jenkins (2001), p. 2.

- ^ a b Butt (1991), p. 78.

- ^ Wenk (2011), p. 7.

- ^ a b "Mass in b minor (b-minor Mass) BWV 232". Bach Digital. Leipzig: Bach Archive; et al. 2019-05-08.

- ^ Alberto Basso. Frau Musika: La vita e le opere di J. S. Bach, Volume II: Lipsia e le opere de la maturità (1723–1750), pp. 510–511. Turin, EDT. 1983. ISBN 88-7063-028-5

- ^ a b c d Butt (1991), p. 93.

- ^ a b c d e f Bach Mass in B Minor (2011).

- ^ a b c d Wenk (2011), p. 5.

- ^ Bach Mass in B Minor (2011), pp. 2–17.

- ^ a b Wolff (1967).

- ^ Butt (1991), p. 77.

- ^ a b Scobel (2006), p. 4.

- ^ Bach Mass in B Minor (2011), pp. 18–25.

- ^ Rathey (2003), p. 6.

- ^ Wenk (2011), pp. 10–11.

- ^ Bach Mass in B Minor (2011), pp. 26–33.

- ^ a b c d Rathey (2003), p. 8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Amati-Camperi (2005).

- ^ a b c d e f g Wenk (2011), p. 13.

- ^ Scobel (2006), p. 5.

- ^ Bach Mass in B Minor (2011), pp. 34–52.

- ^ Bach Mass in B Minor (2011), pp. 53–58.

- ^ Cantata BWV 29 (allofbach.com)

- ^ Pérez Torres (2005), p. 11.

- ^ Bach Mass in B Minor (2011), pp. 59–65.

- ^ Bach Mass in B Minor (2011), pp. 66–75.

- ^ Rathey (2003), p. 10.

- ^ a b c Rathey (2003), p. 11.

- ^ Bach Mass in B Minor (2011), pp. 75–81.

- ^ Pérez Torres (2005), p. 18.

- ^ Bach Mass in B Minor (2011), pp. 82–86.

- ^ Paczkowski (2013), p. 82.

- ^ Bach Mass in B Minor (2011), pp. 87–94.

- ^ Jenkins (2001), p. 7.

- ^ a b Rathey (2003), p. 12.

- ^ Butt (1991), p. 86.

- ^ Bach Mass in B Minor (2011), pp. 95–114.

- ^ a b c d Rathey (2003), p. 14.

- ^ Scobel (2006), p. 7.

- ^ Bach Mass in B Minor (2011), pp. 115–120.

- ^ Butt (1991), pp. 81–82.

- ^ Rathey (2003), pp. 13–14.

- ^ Bach Mass in B Minor (2011), pp. 121–130.

- ^ Bach Mass in B Minor (2011), pp. 131–138.

- ^ Jenkins (2001), p. 3.

- ^ a b c Wolff (2009).

- ^ Bach Mass in B Minor (2011), pp. 139–142.

- ^ Bach Mass in B Minor (2011), pp. 143–147.

- ^ a b Pérez Torres (2005), p. 65.

- ^ a b Bach Mass in B Minor (2011), pp. 148–162.

- ^ Bach Mass in B Minor (2011), pp. 163–169.

- ^ Baxter 2013, p. 5.

- ^ Bach Mass in B Minor (2011), pp. 170–180.

- ^ Scobel (2006), p. 8.

- ^ Bach Mass in B Minor (2011), pp. 180–181.

- ^ Bach Mass in B Minor (2011), pp. 182–191.

- ^ Bach Mass in B Minor (2011), pp. 192–199.

- ^ a b c Rathey (2003), p. 15.

- ^ Bach Mass in B Minor (2011), pp. 199–209.

- ^ Bach Mass in B Minor (2011), pp. 210–229.

- ^ Dürr (1981), p. 670.

- ^ Pérez Torres (2005), p. 88.

- ^ Bach Mass in B Minor (2011), pp. 230–233.

- ^ Bach Mass in B Minor (2011), pp. 234–236.

- ^ Pérez Torres (2005), p. 95.

- ^ Bach Mass in B Minor (2011), pp. 237–243.

- ^ Pérez Torres (2005), p. 129.

Bibliography

- Amati-Camperi, Alexandra (2005). "Notes: Bach B Minor Mass". San Francisco Bach Choir. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Baxter, Jeffrey (2013). "Bach's Creed / Two Views of the Symbolum Nicenum of the Mass in B-Minor" (PDF). ASO Chamber Chorus. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Butt, John (1991). Bach: Mass in B Minor. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-38716-7.

mass in b minor structure.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dürr, Alfred (1981). Die Kantaten von Johann Sebastian Bach (in German). Vol. 1 (4 ed.). Deutscher Taschenbuchverlag. p. 670. ISBN 3-423-04080-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jenkins, Neil (2001). "Bach B Minor Mass" (PDF). Retrieved 4 October 2013.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Libbey, Ted (7 April 2009). "Bach: Essays on his Life and Music". Retrieved 7 October 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Paczkowski, Szymon (2013). Tomita, Yo; Leaver, Robin A.; Smaczny, Jan (eds.). The Role and Significance of the Polonaise in the 'Quoniam' of the B-minor Mass. Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pérez Torres, René (2005). Bach's Mass in B minor: An Analytical Study of Parody Movements and their Function in the Large-Scale Architectural Design of the Mass. University of North Texas. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rathey, Markus (18 April 2003). "Johann Sebastian Bach's Mass in B Minor: The Greatest Artwork of All Times and All People" (PDF). yale.edu. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Rifkin, Joshua (2006). "Preface". Breitkopf. pp. 5–8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Scobel, Cordula (2006). "h-Moll-Messe" (PDF) (in German). Frankfurter Kantorei. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sherman, Bernard D. (August 2004). "Performing Bach's B minor Mass: Thirty Years of HIP". Goldberg. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Talbeck, Carol (2002). "Johann Sebastian Bach: Mass in B Minor / Everything must be possible. – J. S. Bach". sfchoral.org. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Wenk, Arthur (2011). "J.S. Bach and the Mystery of the B Minor Mass" (PDF). arthurwenk.ca. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 December 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wolff, Christoph (1967). "Festschrift Bruno Stäblein zum 70. Geburtstag". In Martin Ruhnke (ed.). Zur musikalischen Vorgeschichte des Kyrie aus Johann Sebastian Bachs Messe in h-moll (in German). Kassel: Bärenreiter. p. 316.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wolff, Christoph (2009). Johann Sebastian Bach. Messe in h-moll.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wolf, Uwe (2011). Preface to the Piano Reduction. Bärenreiter.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bach Mass in B Minor / Piano Reduction based on the Urtext of the New Bach Edition / Revised Version. Bärenreiter. 2011.

- "J.S. Bach Mass in B Minor / Organization of Movements / Comparison with Catholic Mass". California Institute of Technology. 1996. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

External links

- Mass in B minor: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Mass in B minor BWV 232. Text and its translation in several languages, details, list of recordings, reviews and discussions

- Free scores of this work in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Mass in B Minor / Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750). Aylesbury Choral Society, 2004

- Eduard van Hengel, Kees van Houten: "Et incarnatus": An Afterthought? / Against the "Revisionist" View of Bach's B-Minor Mass. Journal of Musicological Research, 2004

- B Minor Mass Explorer worshipanew.net