Germania

Germania (/dʒɜːrˈmeɪniə/ jur-MAY-nee-ə, Latin: [ɡɛrˈmaːnɪ.a]) was the Roman term for the historical region in north-central Europe initially inhabited mainly by Germanic tribes.

The origin of the term "Germania" is uncertain but known to have been used at the age of Julius Caesar, who wrote in the 1st century BC about warlike Germanic tribes and their threat to Roman Gaul and military clashes (Roman-Gallic wars) between the Romans and those tribes. In the late 1st century AD, Tacitus wrote Germania the most complete account of Germania that still survives.

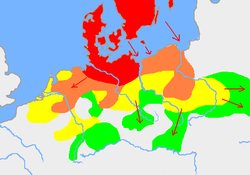

Germania extended from the Danube and Main in the south to the Baltic Sea, and from the Rhine in the west to the Vistula. The Roman portions formed two provinces of the Empire, Germania Inferior to the north (present-day southern Netherlands, Belgium, and western Germany), and Germania Superior to the south (Switzerland, southwestern Germany, and eastern France).

During antiquity, Germania was initially inhabited not only by Germanic tribes, but also Celts, Balts, Scythians, Sarmatians, Alans and later on Early Slavs, Pannonian Avars, and Huns. The population mix changed over time by assimilation, and especially by migration during the Migration Period with many Germanic tribes migrating to the Roman Empire, and a large influx of Slavs.

Etymology

The ethnonym Germani is most likely Gallic in origin. Jacob Grimm derived it from a Celtic term for "shouting; noisy", and argued that the name represents a literal translation of the endonym Tungri. Johann Kaspar Zeuss derived the name from the Celtic word for "neighbour".[1]

Germani enters into Latin use following Julius Caesar, who likely took the word from writings of Posidonius.[2] Caesar in Commentarii de Bello Gallico (written in the 50s BC) reports hearing from his Remi allies that the term Germani was for a group that had historically come from the near side of the Rhine, named Germani Cisrhenani. By extension, Germani was understood to include similar tribes still living beyond the Rhine (Germani Transrhenani).[3]

Tacitus, writing in AD 98, reports that the Tungri of his time, who lived in the area which had been home to the Germani Cisrhenani, had changed their name, but had once been the original Germani:

For the rest, they affirm Germania to be a recent word, lately bestowed. For those who first passed the Rhine and expulsed the Gauls, and are now named Tungrians, were then called Germani. And thus by degrees the name of a tribe prevailed, not that of the nation; so that by an appellation at first occasioned by fear and conquest, they afterwards chose to be distinguished, and assuming a name lately invented were universally called Germani.[4]

Names of Germany in English and some other languages are derived from "Germania", but German speakers call it "Deutschland", and Dutch speakers call it "Duitsland", both from *þeudō "people or nation" (see Theodiscus and Teutons). Several modern languages use the name "Germania", including Hebrew (גרמניה), Italian (Germania), Albanian (Gjermania), Bulgarian (Германия), Maltese (Ġermanja), Greek (Γερμανία), Romanian (Germania), Russian (Германия), Armenian (Գերմանիա) and Georgian (გერმანია).

Geography

Germania extended from the Rhine eastward to the Vistula river, and from the Danube and Main river northward to the Baltic Sea.[5]

The geography of Magna Germania was comprehensively described in Ptolemy's Geography of around 150 AD via geographical coordinates of the main cities. By means of a geodetic deformation analysis carried out by the Institute of Geodesy and Geoinformation Science at the Technical University of Berlin as part of a project of the German Research Association under the direction of Dieter Lelgemann in 2007–2010, many historical place names have been localized and associated with place names of the present day.[6]

The Roman parts of Germania, "Lesser Germania", eventually formed two provinces of the empire, Germania Inferior, "Lower Germania" (which came to eventually include the region of the original germani cisrhenani) and Germania Superior (in modern terms comprising an area of western Switzerland, the French Jura and Alsace regions, and southwestern Germany). Important cities in Lesser Germania included Besançon (Besontio), Strasbourg (Argentoratum), Wiesbaden (Aquae Mattiacae), and Mainz (Mogontiacum).

History

Greek accounts

Classical records show little about the people who inhabited the north of Europe before the 2nd century BC. In the 5th century BC, the Greeks were aware of a group they called Celts (Keltoi). Herodotus also mentioned the Scythians but no other tribes. At around 320 BC, Pytheas of Massalia sailed around Britain and along the northern coast of Europe, and what he found on his journeys was so strange that later writers refused to believe him. He may have been the first person from the Mediterranean to distinguish the Germanic people from the Celts. Contact between German tribes and the Roman Empire did take place and was not always hostile. Recent excavations of the Waldgirmes Forum show signs that a civilian Roman town was established there, which has been interpreted to mean that Romans and Germanic tribesmen were living in peace, at least for a while.[9]

Roman encounters

Caesar described the cultural differences between the Germanic tribesmen, the Romans, and the Gauls in his book Commentarii de Bello Gallico, where he recalls his defeat of the Suebi tribes at the Battle of Vosges. He describes them at length at the beginning of Book IV and the middle of Book VI. He states that the Gauls, although warlike, had a functional society and could be civilized, but that the Germanic tribesmen were far more savage and were a threat to Roman Gaul and Rome itself. Caesar said the Germanic tribes were nomadic, with no notable settlements and a primitive culture. He used this as one of his justifications for why they had to be conquered. His accounts of barbaric northern tribes could be described as an expression of the superiority of Rome, including Roman Gaul.[10]

Caesar's accounts portray the Roman fear of the Germanic tribes and the threat they posed. The perceived menace of the Germanic tribesmen proved accurate. The most complete account of Germania that has been preserved from Roman times is Tacitus' Germania.

The occupied Lesser Germania was divided into two provinces: Germania Inferior (Lower Germania) (approximately corresponding to the southern part of the present-day Netherlands) and Germania Superior (Upper Germania) (approximately corresponding to present-day Switzerland, South West Germany and Alsace).

The Romans under Augustus began to conquer and defeat the peoples of Germania Magna in 12 BC, having the Legati (generals) Germanicus, and Tiberius leading the Legions. By 6 AD, all of Germania up to the River Elbe was temporarily pacified by the Romans as well as being occupied by them, with Publius Quinctilius Varus being appointed as Germania's governor. The Roman plan to complete the conquest and incorporate all of Magna Germania into the Roman Empire was frustrated when three Roman legions under Varus command were annihilated by the German tribesmen in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD. Augustus then ordered Roman withdrawal from Magna Germania (completed by AD 16) and established the boundary of the Roman Empire as being the Rhine and the Danube. Under Emperors Vespasian and Domitian, the Roman Empire occupied the region known as the Agri Decumates between the Main, Danube and Rhine rivers. The region soon became a vital part of the Limes Germanicus with dozens of Roman forts. The Agri Decumates were finally abandoned to the Germanic Alemanni, after the Emperor Probus' death (282).[11]

Population

"While the territory of ancient Germania was clearly dominated in a political sense by Germanic-speaking groups, it has emerged that the population of this vast territory was far from entirely Germanic... [Germanic] expansion did not annihilate the indigenous, non-Germanic population of the areas concerned, so it is important to perceive Germania as meaning Germanic-dominated Europe."[a]

Germania was inhabited by different tribes, most of them Germanic but also some Celtic, Slavic, Baltic, Iranian, Finnic peoples, and also some peoples of unknown ethnic origin.[a] The tribal and ethnic makeup changed over the centuries as a result of assimilation and, most importantly, migrations. All of these peoples were labeled Germani by the Romans.[b]

Some Germani, perhaps the original people to have been referred to by this name, had lived on the west side of the Rhine. At least as early as the 2nd century BC this area was considered[by whom?] to be in "Gaul", and became part of the Roman empire in the course of the Gallic Wars (58–50 BC). These so-called Germani cisrhenani lived in the region of present-day eastern Belgium, the southeastern Netherlands, and stretching into Germany towards the Rhine. The language of the Germani Cisrhenani and their neighbours across the Rhine is still unclear. Their tribal names and personal names are generally considered Celtic, and there are also signs of an older Belgic language which once existed between the contact zone of the Germanic and Celtic languages.

The Germania of Caesar and Tacitus was not defined along linguistic lines as is the case with the modern term "Germanic". The Romans knew of Celtic tribes living in Magna Germania (Greater Germania), and what we now term Germanic tribes living in Gaul, then a predominantly Celtic region. It is also not clear that they distinguished the tribes into linguistic categories in any exact way.

During the period of the Roman empire, more tribes settled in areas of the empire near the Rhine, in territories controlled by the Roman Empire. Eventually these areas came to be known as Lesser Germania, while Greater Germania (Magna Germania; it is also referred to by names referring to its being outside Roman control: Germania libera, "free Germania") formed the larger territory east of the Rhine.

The areas west of the Rhine were mainly Celtic (specifically Gaulish) and became part of the Roman Empire.[14][15]

Germania in its eastern parts was likely also inhabited by early Baltic and, centuries later, Slavic tribes. These parts of eastern Germania are sometimes called Germania Slavica in modern historiography.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b "While the territory of ancient Germania was clearly dominated in a political sense by Germanic-speaking groups, it has emerged that the population of this vast territory was far from entirely Germanic... [Germanic] expansion did not annihilate the indigenous, non-Germanic population of the areas concerned, so it is important to perceive Germania as meaning Germanic-dominated Europe."[12]

- ^ "The Romans, in fact, did not distinguish the peoples living on the north European Plain—who probably spoke Germanic languages— from Celtic speakers in central temperate Europe east of the Rhine and Finnic speakers in the northeast. To the Romans the languages of all the barbarians were more like animal cries than human speech. All were labeled collectively, Germani.[13]

References

- ^ Gustav Solling, Diutiska, an historical and critical survey of the literature of Germany, from the earliest period to the death of Göthe (1863), p. 3.

- ^ Peter Rietbergen (2006): Europe. A Cultural History. ISBN 9780415323598. page 57

- ^ Schulze, Hagen (1998). Germany: A New History. Harvard University Press. p. 4. ISBN 0-674-80688-3.."German", The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology. Ed. T. F. Hoad. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved March 4, 2008.

- ^ Tacitus, Germania 2. Ceterum Germaniae vocabulum recens et nuper additum, quoniam qui primi Rhenum transgressi Gallos expulerint ac nunc Tungri, tunc Germani vocati sint: ita nationis nomen, non gentis evaluisse paulatim, ut omnes primum a victore ob metum, mox etiam a se ipsis, invento nomine Germani vocarentur.

- ^ Laurent Edward, Peter. "A Manual of Ancient Geography". 13 November 2014. H Slatter, 1840, p 163-168, The British Library. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ Kleineberg, Andreas (2010). Kleineberg, Andreas; Marx, Christian; Knobloch, Eberhard; Lelgemann, Dieter (eds.). Germania und die Insel Thule. Die Entschlüsselung von Ptolemaios' "Atlas der Oikumene" [Germania and Thule Island. The Decipherment of Ptolemy's Atlas of the Oikoumene] (in German). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. ISBN 978-3-534-23757-9. OCLC 699749283.

- ^ Kinder, Hermann (1988), Penguin Atlas of World History, vol. I, London: Penguin, p. 108, ISBN 0-14-051054-0.

- ^ "Languages of the World: Germanic languages". The New Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago, IL, United States: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 1993. ISBN 0-85229-571-5.

- ^ Jones, Terry and Alan Ereira (2006), "Terry Jones' Barbarians", p.97. BBC Books, Ltd., London, ISBN 978-0-563-53916-2.

- ^ Frederic Austin Ogg. "A Source Book of Medieval History." American Book Company, New York; pp. 19-21.

- ^ D. Geuenich, Geschichte der Alemannen, p. 23

- ^ Heather 2007, p. 53.

- ^ Waldman & Mason 2006, p. 302.

- ^ Stümpel, Gustav (1932). Name und Nationalität der Germanen. Eine neue Untersuchung zu Poseidonios, Caesar und Tacitus (in German). Leipzig: Dieterich. p. 60. OCLC 10223081.

- ^ Feist, Sigmund (1927). Germanen und Kelten in der antiken Überlieferung (in German). Baden-Baden.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Sources

- Heather, Peter (2007). The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199978618.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|registration=and|subscription=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). "Germanics". Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. pp. 296–330. ISBN 9781438129181.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|subscription=and|registration=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Howatson, M. C., ed. (2011). "Germany". The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature (3 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191739422. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|subscription=(help) - Drinkwater, John Frederick (2012). "Germania". In Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther (eds.). The Oxford Classical Dictionary (4 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191735257. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|subscription=(help) - Claudius Ptolemy (1 March 2011) [150 C.E.]. Geography of Claudius Ptolemy. Translated by Stevenson, Edward Luther. introduction by Joseph Fischer. Cosimo, Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-60520-439-0. OCLC 800793368.; see article at Geography (Ptolemy)

- Malcolm Todd (1995). The Early Germans. Blackwell Publishing.

- Peter S. Wells (2001). Beyond Celts, Germans and Scythians: Archaeology and Identity in Iron Age Europe. Duckworth Publishers.

External links

- Germania (Roman provinces)

- 1849 Harper New York Map, Ancient Germanic Tribes and Towns

- Tacitus' Germania at the Latin Library (text in Latin)

- Tacitus' Germania: English translation (Gordon, c.1910, proofed by Halsall at fordham.edu.)