Rhenish Republic

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2011) |

Rhenish Republic Rheinische Republik | |

|---|---|

| 1923–1924 | |

|

Flag | |

| Status | Unrecognized state |

| Capital | Aachen |

| Government | Republic |

| History | |

• Established | 21 October 1923 |

• Disestablished | 26 November 1924 |

| Today part of | |

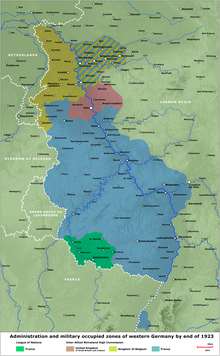

The Rhenish Republic (Template:Lang-de) was proclaimed at Aachen (Aix-la-Chapelle) in October 1923 during the occupation of the Ruhr by troops from France and Belgium (January 1923 – 1925). It comprised three territories, named North, South and Ruhr. Their regional capitals were, respectively, Aachen, Koblenz and Essen.

Background

The Rhenish Republic is best understood as the aspiration of a poorly focused liberation struggle. The name was one applied by the short-lived separatist movement that erupted in the German Rhineland during the politically turbulent years following Germany's defeat in the First World War. The objectives of the many different separatist groups ranged widely, from the foundation of an autonomous republic to some sort of change in the status of the Rhineland within the Weimar Republic. Others advocated full integration of the Rhineland into France. Similar political currents were stirring in the south: June 1919 had seen the proclamation by Eberhard Haaß of the "Pfälzische Republik", centred on Speyer in the occupied territory of the Bavarian Palatinate.

Rhenish separatism in the 1920s should be seen in the context of resentments fostered by economic hardship and the military occupation to which the previously prosperous region was subjected. After 1919, blame for defeat in the Great War was apportioned to (amongst others) the military or simply the French. France, like Germany, had been profoundly traumatised by the Great War and the conduct of her occupation of the left bank of the Rhine was perceived as unsympathetic, even among her Western wartime allies. Increasingly, however, blame was directed against the German government itself, in far-off Berlin. By 1923, as the German currency collapsed, the French occupation forces headquartered at Mainz (under the command of Generals Mangin and Fayolle) were having some success in their encouragement of anti-Berlin separatism in the occupied zones.

After 1924, economic hardship slowly began to ease and a measure of brittle stability returned to Germany under the Weimar State. The appeal of Rhenish separatism, never a mass movement, was damaged by the violence employed by many of its more desperate supporters. The political temperature cooled after the French occupation of the Ruhr attracted increasingly strident criticism from Great Britain and the United States. Following the Dawes Plan in September 1924, an agreement to a slightly less punitive war reparations payment régime, the French vacated the Ruhr in the summer of 1925. The end of the Rhenish Republic can be dated at December 1924, when its leading instigator, Hans Adam Dorten (1880–1963), was obliged to flee to Nice. By 1930, when French troops also vacated the left bank of the Rhine, the concept of a Rhenish Republic, independent of Berlin, no longer attracted popular support.

Historical context

The Cisrhenian Republic (1797–1802) and subsequent incorporation of the region into the French Empire lasted for less than a generation, but introduced to the occupied Rhineland many of the features of the modern state. These were revolutionary and widely welcomed. One objective of the Congress of Vienna in 1815 was to undo Napoléon's territorial changes, so the German Lower Rhine and Westphalia reverted to the Kingdom of Prussia (joined by the Middle Rhine and Cologne), the Palatinate region to Bavaria. Nonetheless, Prussia's western territories continued to adhere to the Napoleonic legal system and, in many other respects, the relationship between the citizen and the state had been permanently transformed. In addition, mutual intolerance of religious differences, stretching back centuries, endured between Protestant Prussia and the predominantly Roman Catholic populations of the Rhineland. The incorporation/reincorporation of most of the Rhineland into Prussia did not run smoothly and remained incomplete more than a century later. Many Rhinelanders continued to regard rule by Prussia as a form of foreign occupation. At the same time, these events occurred during the occupation of the Rhineland by American, Belgian, British and French troops.

Chronology

Dr Adenauer calls a meeting

On 1 February 1919, more than sixty of the Rhineland's civic leaders together with locally based Prussian National Assembly Members convened in Cologne at the invitation of the city's mayor, Konrad Adenauer of the Catholic Center Party. There was only one item on the agendum: "The Creation of the Rhenish Republic" (Template:Lang-de).

In addressing delegates, Adenauer identified the wreckage of Prussian hegemonistic power as the inevitable consequence ("notwendige Folge") of the Prussian system. Prussia was viewed by opponents as "Europe's evil spirit" and was "ruled over by an unscrupulous caste of war-fixated militaristic aristocrats" ("von einer kriegslüsternen, gewissenlosen militärischen Kaste und dem Junkertum beherrscht"). The other German states should, therefore, no longer put up with Prussian supremacy. Prussia must be divided up, and her western provinces separated out to form a West German Republic. This should render impossible future domination of Germany by Prussia's eastern militaristic ethos. Adenauer was, however, keen that his West German Republic should remain inside the German political union.

Agreement on blaming Berlin was the easy part: the complexity of the practical issues to be addressed in defining a federalist agenda for an economically destitute territory that politically, linguistically and legally was part of Germany, but most of which was occupied militarily by France, must have been daunting. In the end, the Cologne meeting produced a two-point resolution. The meeting asserted as valid the right of the Rhineland peoples to political self-determination. The proclamation of a West German Republic was to be deferred, however, so that the Prussian state might be divided up. In this way a practical solution could first be agreed with the occupying power and her allies regarding the issue of reparations.

During the months following Adenauer's meeting, separatist movements with a range of priorities and agendas appeared in many Rhineland towns and villages.

Hans Adam Dorten and the Wiesbaden Proclamation

Hans Adam Dorten (1880–1963), an army reserve officer and former Düsseldorf public prosecutor, made a speech at Wiesbaden, on 1 June 1919, in which he proclaimed "The Independent Rhenish Republic", which was to incorporate the existing Rhineland Province along with parts of Hesse and Bavaria's Upper Rhineland. A non-violent putsch was also attempted across the Rhine in Mainz. This, along with other poorly coordinated localised actions inspired by Dorten's Wiesbaden Proclamation, failed to attract significant popular support and soon failed. The Supreme Court in Leipzig issued an arrest warrant for Dorten, citing 'high treason', but by remaining in the French occupied territories, Dorten made the execution of arrest warrant impossible.

At liberty, Dorten continued his struggle: on 22 January 1922 he founded in Boppard a political party, the "Rhenish Peoples' Union" (Rheinische Volksvereinigung), chaired by Bertram Kastert (1868–1935), a senior Cologne pastor. Thanks to the outstanding treason indictment, Dorten and his circle found themselves shunned by members of the mainstream political parties. The Rhenish Peoples' Union stayed in the shadows, its weekly publication, German Standpoint (Deutsche Warte) and its leaders' other campaigning activities depending on French sponsorship. Dorten moved to France at the end of 1923 and later took French Citizenship.

Occupation of the Ruhr

During 1923, Germany was shaken by adverse international developments and by a dramatic further deterioration in the economic climate: the year was one of crises.

The German government fell into arrears with war reparations payments. In response, on 8 March 1921, French and Belgian troops moved in to occupy Duisburg and Düsseldorf. On 9 January 1923 the Reparations Commission determined that Germany had willfully held back from making payments due, and two days later troops occupied the rest of the Ruhr Area: thus the Rhineland's richest industrial region now bore, on behalf of Germany, the principal burden of the reparations imposed at Versailles. In the fighting that followed more than a hundred people lost their lives. More than 70,000 were turned out in order to make space for French and Belgian workers. Mostly young men, those suddenly evicted and deprived of their livelihoods frequently found themselves homeless and some ended up joining one or other of the various active Rhenish separatist groups. Respectable Rhinelanders, appalled at their unkempt appearance, were inclined to dismiss the dispossessed as work-shy thieving riff-raff ("arbeitsscheues Diebsgesindel").

The currency stability that had underpinned several decades of sustained economic growth in much of Europe well into the second decade of the twentieth century was a casualty of the First World War. The statesmen who devised the Versailles settlement were not economists. Their aspirations did not extend to creating the balanced economic environment needed to support future growth: even at the time their approach to the economic aspects of the Versailles Peace settlement drew strident criticism from John Maynard Keynes, an eminent and closely informed commentator. In 1923, the pre-war price stability remained a distant memory for Europeans, but the occupation of the Ruhr coincided with, and in the view of many commentators triggered, a tipping point for the German currency. Prices escalated: the usefulness of money collapsed and hyperinflation took hold; commerce virtually ceased. Writing in the journal Die Weltbühne (The World Stage), from the perspective of August 1929, the distinguished political commentator Kurt Tucholsky offered an assessment: “There was no appetite in the Rhineland for union with France, but little enthusiasm for continued union with Prussia. All that people wanted, and were entitled to, was an end to the hellish nightmare of hyperinflation and the creation of an autonomous republic with its own currency."

"Government" in Koblenz: Separatism across the Rhineland

Koblenz had been the administrative capital of the Prussian Rhine Province since 1822. Amidst the turmoil of economic collapse, it was here that, on 15 August 1923, the "United Rhenish Movement" (die Vereinigte Rheinische Bewegung) was formed from a merging of several existing separatist groups. Leaders included Dorten of the "Rhenish Peoples' Union" (die Rheinische Volksvereinigung) and a journalist named Josef Friedrich Matthes (1886–1943) of the "Rhenish Independence League" (der Rheinischen Unabhängigkeitsbund) which had been founded by Josef Smeets from Cologne. Another leading figure present was Leo Deckers from Aachen. The unambiguous goal of the United Rhenish Movement was the complete separation of the Rhine Province from Prussia, and the establishment of a Rhenish Republic under French protection. The creation of the republic was to be publicly proclaimed: meetings would be convened across the Rhineland. Endorsement from the French, with their military headquarters in Mainz, was taken for granted: it is not clear what thought was given to the possibility that commanders of France's junior partner in the occupation might take a less benign view of separatist activities just across the border from Belgium's Eupen enclave, west of Aachen, only recently incorporated into Belgium under the terms of the Versailles settlement.

Two months later, ten kilometres to the east of Aachen, the tricolour flag of the Rhenish Republic appeared outside a house in the small town of Eschweiler. Inside, the movement set up a communications center on 19 October 1923. A week after that, the separatists attempted a putsch against the Rathaus. Surrender was refused however: a truce briefly ensued. The next day, the government urged resistance and eventually, on 2 November 1923, Belgian occupation troops expelled the separatists from Eschweiler.

Meanwhile, in Aachen itself, separatists led by Leo Deckers and Dr Guthardt captured the Aachen Rathaus (city hall) where, in the Imperial Chamber, they proclaimed the "Free and Independent Rhenish Republic" on 21 October 1923. The next day the separatists came up against counter demonstrators who surrounded and wrecked their Sekretariat in Friedrich-Wilhelm-Platz, near the theatre. 23 October opened with shooting in the streets: meanwhile the city fire brigade reclaimed the Rathaus, forcing the separatists to retreat to government buildings. That day Belgian troops imposed martial law.

On 25 October, the local police were placed under the command of the Belgian occupation forces after attempting to storm the separatists out of the government buildings, only to find themselves thwarted by occupation troops. Across town, changes at the Technical High School included the exclusion from Aachen of non-resident students.

On 2 November, the Rathaus was retaken by the separatists, now reinforced by around 1000 members of the "Rhineland protection force" (der Rheinland-Schutztruppen). Belgian High Commissar, Baron Rolin-Jaquemyns, responded by ordering an immediate end to the separatist government and called the troops off the streets. The City Council convened in the evening and swore loyalty to the German State (Treuebekenntnis zum Deutschen Reich).

Parallel coup attempts in many Rhenish towns blew up, most of them following much the same pattern. Local government representatives and officials were expelled from civic buildings which were taken over. The Rhenish tricolour was raised over occupied town halls. Notices were posted and leaflets distributed informing citizens of the change of régime. However, civic putsches did not prevail everywhere: in Jülich, Mönchengladbach, Bonn and Erkelenz, separatist attempts to take over public buildings were immediately thwarted, sometimes violently: other districts remained entirely untouched by separatist agitation.

To the north, in Duisburg, separarists inaugurated, on 22 October 1923 a mini-state that would endure for five weeks. Local members of the Rhenish Independence League took to the streets, proclaiming, disingenuously, that their new republic had come into being without any input from the French: attempts to suppress the Duisburg republic more rapidly were nonetheless blocked by the French occupation forces.

Back in Koblenz, the regional capital, separatists had tried to seize power on 21 October 1923. The next day saw hand-to-hand fighting involving the local police. During the night of 23 October, Koblenz Castle, which had been out of the limelight since 1914 when the Kaiser had briefly established his wartime headquarters there, was captured by separatists with French military support. The occupiers were temporarily evicted by local police the following day, only to renew their occupation that night.

On 26 October, the French High Commissioner, Paul Tirard, confirmed that the separatists were in possession of effective power (als Inhaber der tatsächlichen Macht). Subject to the self-evident superior authority of the occupiers, he stated that they needed to introduce all the necessary measures (alle notwendigen Maßnahmen einleiten). Separatist leaders Dorten and Josef Friedrich Matthes interpreted Tirard's intervention as an effective carte blanche from the occupation forces. A cabinet was formed and Matthes, as its chairman, designated "Prime Minister of the Rhenish Republic" (Ministerpräsident der rheinischen Republik).

The new government's power was heavily dependent on finance and support from the French occupation force, as well as on the separatists' own Rhineland Protection Force, which was primarily recruited from men expelled from their homes by the French militarisation of the Ruhr. The "protection force" was poorly equipped: many members were too young to have received any military training. Their implementation of the new government's orders, in the absence of detailed instructions, was rough and ready at best, and sometimes violent. A night-time curfew was imposed and press freedom was greatly curbed. The separatist government received virtually no support from Rhineland government staff who mostly refused to acknowledge its authority or simply stayed away from their desks. In view of its French military backing, the wider population offered Dorten's régime little meaningful support.

From his occupation headquarters in Mainz, General Mangin would no doubt have had a far more richly calibrated appreciation of the possibilities presented by Rhenish separatism than the ministers in far away Paris: it is possible to infer, between the approach of the French commanders on the ground and priorities of the Poincaré government, a disparity which became impossible to overlook once Dorten launched his coup in Koblenz: at the same time Paris was coming under heavy political pressure internationally over the increasingly costly French occupation of the Ruhr. In Koblenz, cabinet meetings were often combative and confused, the leaders Dorten and Matthes proving unable to contain their personal rivalries. The French power-brokers now quickly distanced themselves from the Rhenish Republic project, drastically cutting back on their financial support. The Matthes government issued Rhenish bank notes and ordered an extensive "Requisitioning" exercise: this was the signal for the Rhineland Protection Force to embark upon a level of arbitrary widespread looting which greatly exceeded anything necessary simply for feeding the hungry "protection troops". In many towns and villages the situation slid towards chaos. The civil population became increasingly hostile, and the French military found themselves attempting, with increasing difficulty, to preserve some level of order.

Between 6 and 8 November, a force of Rhineland Protection Force members, calling themselves the Northern Flying Division (Fliegende Division Nord), launched an attack on Maria Laach and the surrounding farmsteads. Nearby in Brohl where two residents, Anton Brühl and Hans Feinlinger, had set up a local force to oppose the attackers, a death squad turned up and engaged in an orgy of plunder reminiscent, according to one commentator, of the Thirty Years’ War. A father and son, belonging to the villagers' resistance force, were shot.

10 November saw an outburst of looting at Linz am Rhein: the Rathaus was taken over and the Bürgermeister was forced from office. From here the looters moved on to Unkel, Bruchhausen and Rheinbreitbach, on the southern rim of the Siebengebirge district. All sorts of items of evident value were "requisitioned" in addition to food and vehicles.

On 12 November, the separatists gathered together close by in Bad Honnef, there intending to establish a new headquarters. The Rathaus was taken over and, two days later, the Rhenish Republic proclaimed. Food and liquor were seized in numerous hotels and residences and a large celebration took place in the Kurhaus (Health and Recreation Spa center), during which the Kurhaus furnishings went up in flames.

Siebengebirge insurrection

The Siebengebirge district consists of a series of low wooded hills wedged between the A3 Autobahn and Königswinter, a resort town on the east bank of the Rhine. Back in 1923, the construction of the A3 lay more than a decade in the future, and Bonn, located across the river from Königswinter, could still be described without irony as "a small town in Germany". It was the turn of the village called Aegidienberg to claim a place in history. On the evening of 14 November, a large number of the residents from the various small towns and villages surrounding Bad Honnef met together in an Aegidienberg guest house and resolved to resist openly the wave of looting which, they anticipated, was moving towards the southern side of the Siebengebirge area. The district was experiencing growing food shortages. Despite the weapons ban in force, the group were able to bring together a substantial arsenal, comprising not merely axes, sticks and pitchforks, but also a number of hunting weapons and handguns and other infantry weapons, presumably left over from the war. A mining engineer and former army officer named Hermann Schneider took on leadership of this ad hoc militia.

It was thought that Schneider's Aegidienberg-based force now comprised about 4000 armed men. Using factory sirens and alarm bells, the local troops would be mobilised the minute separatist forces were reported or even merely rumoured to have appeared. Panic was apparent as people rushed around trying to move to safety their cattle and other chattels.

During the afternoon of 15 November, a group of separatists drove two trucks into the Himberg quarter of Aegidienberg: here they were confronted by around 30 armed quarry workers. Peter Staffel, an 18-year-old blacksmith, was shot dead when he forced the trucks to stop and tried to persuade the occupants to turn back. The quarry workers thereupon showered bullets on the separatists who turned and fled along the little Schmelz valley As they fled down the twisting road, back towards Bad Honnef they encountered the local militia, well dug in and waiting for them: Schneider's men seized the trucks and then routed the separatist gang.

That evening the repulsed separatists met up at the Gasthof Jagdhaus, down the Schmelz valley, and called up reinforcements. They planned a more substantial attack for the next day, in order to make an example of Aegidienberg. Accordingly, on 16 November, some 80 armed separatists found a gap in Schneider's defences at a hamlet called Hövel: here they seized five villagers as hostages, tied them up, and placed them in the line of fire between themselves and the now-gathering militiamen. One of the hostages, Theodor Weinz, was shot in the stomach, dying soon afterwards as a result of his injuries.

Meanwhile, more local defenders hurried to the fray and set about the invaders. 14 of the separatists were killed: these were later buried in a mass grave back in Aegidienberg, without the benefit of any identifying inscription. According to contemporaries, the dead men had come originally from the Kevelaer and Krefeld areas, between the Ruhr and the Dutch border.

In order to prevent further fighting, the French installed in Aegidienberg a force of French-Moroccan soldiers for the next few weeks, while military police arrived to conduct an on-the-spot investigation. The investigation concluded that in total around 120 people had been killed in connection with the events of those November days. More precise information on the deaths and other events of the Aegidienberg "insurrection" may survive within the archives of the French gendarmes. Theodor Weinz, the separatists' hostage who had been fatally shot at Hövel, was buried in the Aegidienberg cemetery, near to its main entrance: the primary school has been named after him. Peter Staffel, the young man who had probably been the first fatality of the Siebengebirge insurrection, is buried in the cemetery at the nearby village of Eudenbach (now incorporated within the administrative ambit of Königswinter).

End of the Rhenish Republic

Following the events in Aegidienberg, the separatist cabinet based at the castle in Koblenz split into two camps. Across the province separatist governments were evicted from the Rathausen and in some instances arrested by the French military. Leo Deckers resigned his office on 27 November. On 28 November 1923, Matthes announced that he had dissolved the separatist government.[1] Dorten had already, on 15 November, moved to Bad Ems and there established a provisional government covering the southern part of the Rhineland and the Palatinate and participated actively in the activities of the "Pfälzische Republik" movement, centred on Speyer, which would survived through till 1924. At the end of 1923, Dorten fled to Nice: later he relocated to the US, where he published his memoirs; Dorten was still in exile when he died in 1963.

Joseph Matthes also made his way to France where he later met up with fellow journalist Kurt Tucholsky. Despite the amnesty set out in the London Agreement of August 1924, Matthes and his wife were prevented from returning to Germany, leading Tuckolsky to publish in 1929 his essay entitled For Joseph Matthes, from which are drawn his observations on conditions in the Rhineland in 1923, cited above.

In the towns, the remaining separatist Burgermeister found themselves voted out of office at the end of 1923 or were, for their activities, before the courts.

Konrad Adenauer, who during the period of the "Koblenz Government" had constantly been at odds with Dorten, presented to the French generals another proposal, for the creation of a west German autonomous federal state (die Bildung eines Autonomen westdeutschen Bundesstaates). Adenauer's proposal failed to impress either the French or the German government at this time, however.

See also

References

- This article is based on Rheinische Republik, the equivalent article from the German Wikipedia.

- ^ "Separatists Split; Matthes Is Ousted. Active Head Is Overthrown by Secretary, Rosenbaum, and Coblenz Force". New York Times. 29 November 1923. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

Joseph Matthes chief of the "Rhineland Republic," announced today that he had dissolved the Separatist Government at Coblenz. He is back at Dusseldorf, where he told the New York Times correspondent he intended "to start the movement afresh along better lines, freed from compromising elements which had done no much to discredit it."

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

- 1923 establishments in Europe

- 1924 disestablishments in Europe

- 20th century in North Rhine-Westphalia

- 20th century in Rhineland-Palatinate

- History of the Rhineland

- Former states and territories of North Rhine-Westphalia

- Former states and territories of Rhineland-Palatinate

- Independence movements

- Separatism in Germany

- States and territories established in 1923

- Weimar Republic

- Rhenish nationalism

- Rhine Province