Epidemiology of HIV/AIDS

This article needs to be updated. (November 2014) |

HIV/AIDS, or Human Immunodeficiency Virus, is considered by some authors a global pandemic.[1] However, the WHO currently uses the term 'global epidemic' to describe HIV.[2] As of 2018, approximately 37.9 million people are infected with HIV globally.[3][3] There were about 770,000 deaths from AIDS in 2018.[4] The 2015 Global Burden of Disease Study, in a report published in The Lancet, estimated that the global incidence of HIV infection peaked in 1997 at 3.3 million per year. Global incidence fell rapidly from 1997 to 2005, to about 2.6 million per year, but remained stable from 2005 to 2015.[5]

Sub-Saharan Africa is the region most affected. In 2018, an estimated 61% of new HIV infections occurred in this region.[3] Prevalence ratios are "In western and central Europe and North America, low and declining incidence of HIV and mortality among people infected with HIV over the last 17 years has seen the incidence:prevalence ratio fall from 0.06 in 2000 to 0.03 in 2017. Strong and steady reductions in new HIV infections and mortality among people infected with HIV in eastern and southern Africa has pushed the ratio down from 0.11 in 2000 to 0.04 in 2017. Progress has been more gradual in Asia and the Pacific (0.05 in 2017), Latin America (0.06 in 2017), the Caribbean (0.05 in 2017) and western and central Africa (0.06 in 2017). The incidence:prevalence ratios of the Middle East and North Africa (0.08 in 2017) and eastern Europe and central Asia (0.09 in 2017)".[3] South Africa has the largest population of people with HIV of any country in the world, at 7.06 million [6] as of 2017. In Tanzania, HIV/AIDS was reported to have a prevalence of 4.5% among Tanzanian adults aged 15–49 in 2017.[7]

South & South-East Asia (a region with about 2 billion people as of 2010, over 30% of the global population) has an estimated 4 million cases (12% of all people infected with HIV), with about 250,000 deaths in 2010.[8] Approximately 2.5 million of these cases are in India, where however the prevalence is only about 0.3% (somewhat higher than that found in Western and Central Europe or Canada).[9] Prevalence is lowest in East Asia at 0.1%.[8]

In 2017, approximately 1 million people in the United States had HIV; 14% did not realize that they were infected.[10]

In 2017, 93,385 people (64,472 men and 28,877 women) living with diagnosed HIV infection received HIV care in the UK and 428 deaths.[11] 42,739 (nearly 50%) of those are gay or bisexual, a small segment of the overall population.

In Australia, as of 2017, there were about 27,545 cases.[12] In Canada as of 2016, there were about 63,110 cases.[13][14]

A reconstruction of its genetic history shows that the HIV pandemic almost certainly originated in Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, around 1920.[15][16] AIDS was first recognized in 1981, in 1983 the HIV virus was discovered and identified as the cause of AIDS, and by 2009 AIDS caused nearly 30 million deaths.[17][18][19]

Global HIV data

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2020) |

Currently as of 2019, there are 37.9 million cases of HIV world wide. Out of this amount, in June of 2019, there were 24 million people undergoing antiretroviral therapy. A total of 32 million people have died of HIV since the outbreak began. About 1 million people have died at the end of 2018.[20]

HIV in World – historical data for selected countries

HIV/AIDS in World from 2001 to 2014 – adult prevalence rate – data from CIA World Factbook[21]

| HIV in World in 2014 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region/Country | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2009 | 2007 | 2003 | 2001 | |

| World | 0.79% | NA | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.8% | NA | NA | |

| Africa | ||||||||

| North Africa | ||||||||

| Sudan | 0.25% | 0.24% | NA | 1.1% | 1.4% | NA | 2.3% | |

| Egypt | 0.02% | 0.02% | NA | <0.1% | NA | NA | <0.1% | |

| Libya | NA | NA | 0.3% | NA | NA | NA | 0.3% | |

| Tunisia | 0.04% | 0.05% | NA | <0.1% | <0.1% | <0.1% (2005) | NA | |

| Algeria | 0.04% | 0.1% | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | 0.1% | |

| Morocco | 0.14% | 0.16% | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | 0.1% | |

| Mauritania | 0.92% | NA | 0.4% | 0.7% | 0.8% | 0.6% | NA | |

| Western Africa | ||||||||

| Senegal | 0.53% | 0.46% | NA | 0.9% | 1% | 0.8% | NA | |

| The Gambia | 1.82% | 1.2% | NA | 2% | 0.9% | 1.2% | NA | |

| Guinea Bissau | 3.69% | 3.74% | NA | 2.5% | 1.8% | 10% | NA | |

| Guinea | 1.55% | 1.74% | NA | 1.3% | 1.6% | 3.2% | NA | |

| Sierra Leone | 1.4% | 1.55% | NA | 1.6% | 1.7% | NA | 7% | |

| Liberia | 1.17% | 1.09% | NA | 1.5% | 1.7% | 5.9% | NA | |

| Cote d'Ivore | 3.46% | 2.67% | NA | 3.4% | 3.9% | 7% | NA | |

| Ghana | 1.47% | 1.3% | NA | 1.8% | 1.9% | 3.1% | NA | |

| Togo | 2.4% | 2.33% | NA | 3.2% | 3.3% | 4.1% | NA | |

| Benin | 1.14% | 1.13% | NA | 1.2% | 1.2% | 1.9% | NA | |

| Nigeria | 3.17% | 3.17% | NA | 3.6% | 3.1% | 5.4% | NA | |

| Niger | 0.49% | 0.4% | NA | 0.8% | 0.8% | 1.2% | NA | |

| Burkina Faso | 0.94% | NA | 1% | 1.2% | 1.6% | 4.2% | NA | |

| Mali | 1.42% | 0.86% | NA | 1% | 1.5% | 1.9% | NA | |

| Cape Verde | 1.09% | 0.47% | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.04% | |

| Central Africa | ||||||||

| Chad | 2.53% | 2.48% | NA | 3.4% | 3.5% | 4.8% | NA | |

| Cameroon | 4.77% | 4.27% | NA | 5.3% | 5.1% | 6.9% | NA | |

| Central African Republic | 4.25% | 3.82%% | NA | 4.7% | 6.3% | 13.5% | NA | |

| São Tomé and Príncipe | 0.78% | 0.64% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Equatorial Guinea | 6.16% | NA | 6.2% | 5% | 3.4% | NA | 3.4% | |

| Gabon | 3.91% | 3.9% | NA | 5.2% | 5.9% | 8.1% | NA | |

| Republic of the Congo | 2.75% | 2.49% | NA | 3.4% | 3.5% | 4.9% | NA | |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 1.04% | 1.08% | NA | NA | NA | 4.2% | NA | |

| Angola | 2.41% | 2.35% | NA | 2% | 2.1% | 3.9% | NA | |

| Eastern Africa | ||||||||

| Eritrea | 0.68% | 0.62% | NA | 0.8% | 1.3% | 2.7% | NA | |

| Djibouti | 1.59% | 0.91% | NA | 2.5% | 3.1% | 2.9% | NA | |

| Somalia | 0.55% | 0.53% | NA | 0.7% | 0.5% | NA | 1% | |

| Ethiopia | 1.15% | 1.2% | NA | NA | 2.1% | 4.4% | NA | |

| South Sudan | 2.71% | 2.24% | NA | 3.1% | NA | NA | NA | |

| Kenya | 5.3% | 6.04% | NA | 6.3% | NA | 6.7% | NA | |

| Uganda | 7.25% | 7.44% | NA | 6.5% | 5.4% | 4.1% | NA | |

| Rwanda | 2.82% | 2.85% | NA | 2.9% | 2.8% | 5.1% | NA | |

| Burundi | 1.11% | 1.03% | NA | 3.3% | 2% | 6% | NA | |

| Tanzania | 5.34% | 4.95% | NA | 5.6% | 6.2% | 8.8% | NA | |

| Malawi | 10.04% | 10.25% | NA | 11% | 11.9% | 14.2% | NA | |

| Mozambik | 10.58% | 10.75% | NA | 11.5% | 12.5% | 12.2% | NA | |

| Zambia | 12.37% | 12.5% | NA | 13.5% | 15.2% | 16.5% | NA | |

| Zimbabwe | 16.74% | 14.99% | NA | 14.3% | 15.3% | NA | 24.6% | |

| Madagascar | 0.29% | 0.4% | NA | 0.2% | 0.1% | 1.7% | NA | |

| Comoros | NA | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | <0.1% | NA | 0.12% | |

| Mauritius | 0.92% | 1.1% | NA | 1% | 1.7% | NA | 0.1% | |

| Southern Africa | ||||||||

| Namibia | 15.97% | 14.3% | NA | 13.1% | 15.3% | 21.3% | NA | |

| Botswana | 25.16% | 21.86% | NA | 24.8% | 23.9% | 37.3% | NA | |

| Swaziland | 27.73% | 27.36% | NA | 25.9% | 26.1% | 38.8% | NA | |

| Lesotho | 23.39% | 22.95% | NA | 23.6% | 23.2% | 28.9% | NA | |

| South Africa | 18.92% | 19.05% | NA | 17.8% | 18.1% | 21.5% | NA | |

| Asia | ||||||||

| Western Asia | ||||||||

| Georgia | 0.28% | 0.27% | NA | 0.1% | <0.1% | NA | <0.1% | |

| Armenia | 0.22% | 0.19% | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | |

| Azerbaijan | 0.14% | 0.16% | NA | 0.1% | <0.2%% | <0.1% | NA | |

| Turkey | NA | NA | <0.1% | <0.1% | NA | NA | <0.1% | |

| Iran | 0.14% | 0.14% | NA | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% (2005) | NA | |

| Iraq | NA | NA | <0.1% | NA | NA | NA | <0.1% | |

| Syria | 0.01% | NA | <0.1% | NA | NA | NA | <0.1% | |

| Jordan | NA | NA | <0.1% | NA | NA | NA | <0.1% | |

| Lebanon | 0.06% | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | 0.1% | |

| Israel | NA | NA | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.1% | NA | 0.1% | |

| Yemen | 0.05% | 0.04% | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.1% | |

| Oman | 0.16% | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | NA | 0.1% | |

| United Arab Emirates | NA | NA | 0.2% | NA | NA | NA | 0.18% | |

| Qatar | NA | NA | <0.1% | <0.1% | NA | NA | 0.09% | |

| Bahrain | NA | NA | 0.2% | NA | NA | NA | 0.2% | |

| Kuwait | NA | NA | 0.1% | NA | NA | NA | 0.12% | |

| Central Asia | ||||||||

| Kazakhstan | NA | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | 0.2% | |

| Uzbekistan | 0.15% | 0.18% | NA | 0.1% | <0.1% | NA | <0.1% | |

| Turkmenistan | NA | NA | <0.1% | NA | <0.1% | <0.1% (2004) | NA | |

| Kyrgyzstan | 0.26% | 0.24% | NA | 0.3% | <0.1% | NA | <0.1% | |

| Tajikistan | 0.35% | 0.31% | NA | 0.2% | <0.3% | NA | <0.1% | |

| Afghanistan | 0.04% | NA | <0.1% | NA | NA | NA | <0.1% | |

| Southern Asia | ||||||||

| Pakistan | 0.09% | 0.07% | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | 0.1% | |

| Nepal | 0.2% | 0.23% | NA | 0.4% | 0.5% | NA | 0.5% | |

| Bhutan | NA | 0.13% | NA | 0.2% | <0.1% | NA | <0.1% | |

| India | NA | 0.26% | NA | 0.3% | 0.3% | NA | 0.9% | |

| Bangladesh | 0.01% | 0.01% | NA | <0.1% | NA | NA | <0.1% | |

| Sri Lanka | 0.03% | 0.02% | NA | <0.1% | NA | NA | <0.1% | |

| Maldives | NA | 0.01% | NA | <0.1% | NA | NA | 0.1% | |

| Southeastern Asia | ||||||||

| Myanmar (Burma) | 0.69% | 0.61% | NA | 0.6% | 0.7% | 1.2% | NA | |

| Thailand | 1.13% | 1.09% | NA | 1.3% | 1.4% | 1.5% | NA | |

| Laos | 0.26% | 0.15% | NA | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.1% | NA | |

| Cambodia | 0.64% | 0.74% | NA | 0.5% | 0.8% | 2.6% | NA | |

| Vietnam | 0.47% | 0.4% | NA | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.4% | NA | |

| Malaysia | 0.45% | 0.44% | NA | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.4% | NA | |

| Singapore | NA | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.2% | NA | |

| Brunei | NA | NA | <0.1% | NA | NA | <0.1% | NA | |

| Philippines | NA | NA | 0.1% | <0.1% | NA | <0.1% | NA | |

| Indonesia | 0.47% | 0.46% | NA | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.1% | NA | |

| Eastern Asia | ||||||||

| Mongolia | NA | 0.04% | NA | <0.1% | <0.1% | <0.1% | NA | |

| Japan | NA | NA | <0.1% | <0.1% | NA | <0.1% | NA | |

| South Korea | NA | NA | <0.1% | <0.1% | <0.1% | <0.1% | NA | |

| China | NA | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | |

| Hong Kong | NA | NA | 0.1% | NA | NA | 0.1% | NA | |

| Australia and Oceania | ||||||||

| Australia | NA | 0.17% | NA | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.1% | NA | |

| New Zealand | NA | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | |

| Papua New Guinea | 0.72% | 0.65% | NA | 0.9% | 1.5% | 0.6% | NA | |

| Fiji | 0.13% | 0.1% | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | |

| Americas | ||||||||

| North America | ||||||||

| Canada | NA | NA | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.3% | NA | |

| Mexico | 0.23% | 0.23% | NA | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.3% | NA | |

| USA | NA | NA | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.6% | NA | |

| Bermuda | NA | 0.3% | NA | NA | 0.3% (2005) | NA | ||

| Central America | ||||||||

| Belize | 1.18% | 1.49% | NA | 2.3% | 2.1% | 2.4% | NA | |

| Guatemala | 0.54% | 0.59% | NA | 0.8% | 0.8% | 1.1% | NA | |

| El Salvador | 0.53% | 0.53% | NA | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.7% | NA | |

| Honduras | 0.42% | 0.47% | NA | 0.8% | 0.7% | 1.8% | NA | |

| Nicaragua | 0.27% | 0.19% | NA | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | NA | |

| Costa Rica | 0.26% | 0.23% | NA | 0.3% | 0.4% | 0.6% | NA | |

| Panama | 0.65% | 0.65% | NA | 0.9% | 1% | 0.9% | NA | |

| Caribbean | ||||||||

| The Bahamas | NA | 3.22% | NA | 3.1% | 3% | 3% | NA | |

| Cuba | 0.25% | 0.23% | NA | 0.1% | <0.1% | <0.1% | NA | |

| Jamaica | 1.62% | 1.75% | NA | 1.7% | 1.6% | 1.2% | NA | |

| Haiti | 1.93% | 1.97% | NA | 1.9% | 2.2% | 5.6% | NA | |

| Dominican Republic | 1.04% | 0.7% | NA | 0.9% | 1.1% | 1.7% | NA | |

| Barbados | NA | 0.88% | NA | 1.4% | 1.2% | 1.5% | NA | |

| Trinidad and Tobago | NA | 1.65% | NA | 1.5% | 1.5% | 3.2% | NA | |

| South America | ||||||||

| Suriname | 1.02% | 0.88% | NA | 1% | 2.4% | 1.7% | ||

| Guyana | 1.81% | 1.38% | NA | 1.2% | 2.5% | 2.5% | NA | |

| Venezuela | 0.55% | 0.56% | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.7% | |

| Colombia | 0.4% | 0.45% | NA | 0.5% | 0.6% | 0.7% | NA | |

| Ecuador | 0.34% | 0.41% | NA | 0.4% | 0.3% | 0.3% | NA | |

| Peru | 0.36% | 0.35% | NA | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.5% | NA | |

| Bolivia | 0.29% | 0.25% | NA | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.1% | NA | |

| Chile | 0.29% | 0.33% | NA | 0.4% | 0.3% | 0.3% | NA | |

| Paraguay | 0.41% | 0.4% | NA | 0.3% | 0.6% | 0.5% | NA | |

| Uruguay | 0.7% | 0.71% | NA | 0.5% | 0.6% | NA | 0.3% | |

| Argentina | 0.47% | NA | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.5% | NA | 0.7% | |

| Brazil | NA | 0.55% | NA | NA | 0.6% | 0.7% | NA | |

| Europe | ||||||||

| Russia | NA | NA | 1% | 1% | 1% | NA | 1.1% | |

| Ukraine | NA | 0.83% | NA | 1.1% | 1.6% | 1.4% | NA | |

| Estonia | NA | 1.3% | NA | 1.2% | 1.3% | NA | 1.1% | |

| Latvia | NA | NA | 0.7% | 0.7% | 0.8% | NA | 0.6% | |

| Lithuania | NA | NA | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | 0.1% | |

| Belarus | 0.52% | 0.49% | NA | 0.3% | 0.2% | NA | 0.3% | |

| Poland | 0.07% | NA | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | 0.1% | |

| Moldova | 0.63% | 0.61% | NA | 0.4% | 0.4% | NA | 0.2% | |

| Romania | NA | 0.11% | NA | 0.1% | <0.1% | NA | <0.1% | |

| Bulgaria | NA | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | NA | <0.1% | |

| Czech Republic | NA | 0.05% | NA | <0.1% | NA | NA | <0.1% | |

| Slovakia | 0.02% | NA | <0.1% | <0.1% | NA | NA | <0.1% | |

| Slovenia | 0.08% | NA | <0.1% | <0.1% | <0.1% | NA | <0.1% | |

| Hungary | NA | NA | <0.1% | <0.1% | 0.1% | NA | 0.1% | |

| Croatia | NA | NA | <0.1% | <0.1% | <0.1% | NA | <0.1% | |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | NA | NA | <0.1% | NA | <0.1% | NA | <0.1% | |

| Serbia | NA | 0.05% | NA | 0.1% | NA | NA | NA | |

| Albania | NA | 0.04% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Macedonia | NA | 0.01% | NA | NA | <0.1% | NA | <0.1% | |

| Greece | NA | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.2% | NA | 0.2% | |

| Cyprus | NA | 0.06% | NA | NA | NA | 0.1% | NA | |

| Malta | NA | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | 0.2% | |

| Italy | NA | 0.28% | NA | 0.3% | 0.4% | NA | 0.5% | |

| Portugal | NA | NA | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.5% | NA | 0.4% | |

| Spain | NA | 0.42% | NA | 0.4% | 0.5% | NA | 0.7% | |

| France | NA | NA | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.4% | NA | |

| Netherlands | NA | NA | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | NA | 0.2% | |

| Belgium | NA | NA | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | NA | |

| Luxembourg | NA | NA | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.2% | NA | 0.2% | |

| Switzerland | NA | 0.35% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | NA | |

| Austria | NA | NA | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.3% | NA | |

| Germany | NA | 0.15% | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | 0.1% | |

| Denmark | 0.16% | 0.16% | NA | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | NA | |

| Finland | NA | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | <0.1% | <0.01% | NA | |

| Sweden | NA | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | 0.1% | |

| Norway | NA | NA | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | NA | 0.1% | |

| Iceland | NA | NA | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.2% | NA | 0.2% | |

| Ireland | NA | NA | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | NA | 0.1% | |

| United Kingdom | NA | 0.33% | NA | 0.2% | 0.2% | NA | 0.2% | |

By region

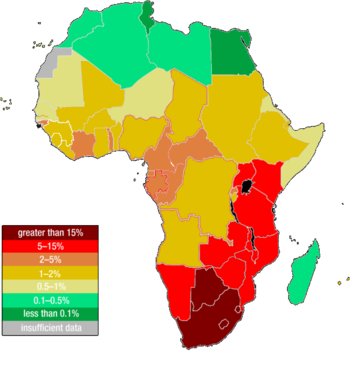

The pandemic is not homogeneous within regions, with some countries more afflicted than others. Even at the country level, there are wide variations in infection levels between different areas. The number of people infected with HIV continues to rise in most parts of the world, despite the implementation of prevention strategies, Sub-Saharan Africa being by far the worst-affected region, with an estimated 22.9 million at the end of 2010, 68% of the global total.[22]

South and South East Asia have an estimated 12% of the global total.[23] The rate of new infections has fallen slightly since 2005 after a more rapid decline between 1997 and 2005.[22] Annual AIDS deaths have been continually declining since 2005 as antiretroviral therapy has become more widely available.

| World region[22] | Estimated prevalence of HIV infection (millions of adults and children) |

Estimated adult and child deaths during 2010 | Adult prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Worldwide | 31.6–35.2 | 1.6–1.9 million | 0.8% |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 21.6–24.1 | 1.2 million | 5.0% |

| South and South-East Asia | 3.6–4.5 | 250,000 | 0.3% |

| Eastern Europe and Central Asia | 1.3–1.7 | 90,000 | 0.9% |

| Latin America | 1.2–1.7 | 67,000 | 0.4% |

| North America | 1–1.9 | 20,000 | 0.6% |

| East Asia | 0.58–1.1 | 56,000 | 0.1% |

| Western and Central Europe | .77–.93 | 9,900 | 0.2% |

Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa remains the hardest-hit region. HIV infection is becoming endemic in sub-Saharan Africa, which is home to just over 12% of the world’s population but two-thirds of all people infected with HIV.[22] The adult HIV prevalence rate is 5.0% and between 21.6 million and 24.1 million total are affected.[22] However, the actual prevalence varies between regions. Presently, Southern Africa is the hardest hit region, with adult prevalence rates exceeding 20% in most countries in the region, and 30% in Swaziland and Botswana. Analysis of prevalence across sub-Saharan Africa between 2000 and 2017 found high variation in prevalence at a subnational level, with some countries demonstrating a more than five-fold difference in prevalence between different districts.[25]

Eastern Africa also experiences relatively high levels of prevalence with estimates above 10% in some countries, although there are signs that the pandemic is declining in this region. West Africa on the other hand has been much less affected by the pandemic. Several countries reportedly have prevalence rates around 2 to 3%, and no country has rates above 10%. In Nigeria and Côte d'Ivoire, two of the region's most populous countries, between 5 and 7% of adults are reported to carry the virus.

Across Sub-Saharan Africa, more women are infected with HIV than men, with 13 women infected for every 10 infected men. This gender gap continues to grow. Throughout the region, women are being infected with HIV at earlier ages than men. The differences in infection levels between women and men are most pronounced among young people (aged 15–24 years). In this age group, there are 36 women infected with HIV for every 10 men. The widespread prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases, the promiscuous culture,[26] the practice of scarification, unsafe blood transfusions, and the poor state of hygiene and nutrition in some areas may all be facilitating factors in the transmission of HIV-1 (Bentwich et al., 1995).

Mother-to-child transmission is another contributing factor in the transmission of HIV-1 in developing nations. Due to a lack of testing, a shortage in antenatal therapies and through the feeding of contaminated breast milk, 590,000 infants born in developing countries are infected with HIV-1 per year. In 2000, the World Health Organization estimated that 25% of the units of blood transfused in Africa were not tested for HIV, and that 10% of HIV infections in Africa were transmitted via blood.

Poor economic conditions (leading to the use of dirty needles in healthcare clinics) and lack of sex education contribute to high rates of infection. In some African countries, 25% or more of the working adult population is HIV-positive. Poor economic conditions caused by slow onset-emergencies, such as drought, or rapid onset natural disasters and conflict can result in young women and girls being forced into using sex as a survival strategy.[27] Worse still, research indicates that as emergencies, such as drought, take their toll and the number of potential 'clients' decreases, women are forced by clients to accept greater risks, such as not using contraceptives.[27]

AIDS-denialist policies have impeded the creation of effective programs for distribution of antiretroviral drugs. Denialist policies by former South African President Thabo Mbeki's administration led to several hundred thousand unnecessary deaths.[28][29] UNAIDS estimates that in 2005 there were 5.5 million people in South Africa infected with HIV — 12.4% of the population. This was an increase of 200,000 people since 2003.

Although HIV infection rates are much lower in Nigeria than in other African countries, the size of Nigeria's population meant that by the end of 2003, there were an estimated 3.6 million people infected. On the other hand, Uganda, Zambia, Senegal, and most recently Botswana have begun intervention and educational measures to slow the spread of HIV, and Uganda has succeeded in actually reducing its HIV infection rate.

Middle East and North Africa

HIV/AIDS prevalence among the adult population (15-49) in the Middle East and North Africa is estimated less than 0.1 between 1990 and 2018. This is the lowest prevalence rate compared to other regions in the world.[30]

In the MENA, roughly 240,000 people are living with HIV as of 2018[31] and Iran accounted for approximately one-quarter (61,000) of the population with HIV followed by Sudan (59,000).[31] As well as, Sudan (5,200), Iran (4,400) and Egypt (3,600) took up more than 60% of the number of new infections in the MENA (20,000). Roughly two-thirds of AIDS-related deaths in this region happened in these countries for the year 2018.[31]

Although the prevalence is low, concerns remain in this region. First, unlike the global downward trend in new HIV infections and AIDS-related deaths, the numbers have continuously increased in the MENA.[32] Second, compared to the global rate of antiretroviral therapy (62%),[33] the MENA region’s rate is far below (32%).[31] The low participation of ART increases not only the number of AIDS-related deaths but the risk of mother-to-baby HIV infections, in which the MENA (24.7%) shows relatively high rates compared to other regions, for example, southern Africa (10%), Asia and the Pacific (17%).[30]

Key population at high risk in this region is identified as injection drug users, female sex workers and men who have sex with men.[30]

South and South-East Asia

The geographical size and human diversity of South and South-East Asia have resulted in HIV epidemics differing across the region.

In South and Southeast Asia, the HIV epidemic remains largely concentrated in injecting drug users, men who have sex with men (MSM), sex workers, and clients of sex workers and their immediate sexual partners.[34] In the Philippines, in particular, sexual contact between males comprise the majority of new infections. An HIV surveillance study conducted by Dr. Louie Mar Gangcuangco and colleagues from the University of the Philippines-Philippine General Hospital showed that out of 406 MSM tested for HIV in Metro Manila, HIV prevalence was 11.8% (95% confidence interval: 8.7- 15.0).[35][36]

Migrants, in particular, are vulnerable and 67% of those infected in Bangladesh and 41% in Nepal are migrants returning from India.[34] This is in part due to human trafficking and exploitation, but also because even those migrants who willingly go to India in search of work are often afraid to access state health services due to concerns over their immigration status.[34]

East Asia

The national HIV prevalence levels in East Asia is 0.1% in the adult (15–49) group. However, due to the large populations of many East Asian nations, this low national HIV prevalence still means that large numbers of people are infected with HIV. The picture in this region is dominated by China. Much of the current spread of HIV in China is through injecting drug use and paid sex. In China, the number was estimated at between 430,000 and 1.5 million by independent researchers, with some estimates going much higher.

In the rural areas of China, where large numbers of farmers, especially in Henan province, participated in unclean blood transfusions; estimates of those infected are in the tens of thousands. In Japan, just over half of HIV/AIDS cases are officially recorded as occurring amongst homosexual men, with the remainder occurring amongst heterosexuals and also via drug abuse, in the womb or unknown means.

In East Asia, men who have sex with men account for 18% of new HIV/AIDS cases and are therefore a key affected group along with sex workers and their clients who makeup 29% of new cases. This is also a noteworthy aspect because men who have sex with men had a prevalence of at least 5% or higher in countries in Asia and Pacific.[37]

Americas

Caribbean

The Caribbean is the second-most affected region in the world.[22] Among adults aged 15–44, AIDS has become the leading cause of death. The region's adult prevalence rate is 0.9%.[22] with national rates ranging up to 2.7%.[38] HIV transmission occurs largely through heterosexual intercourse. A greater number of people who get infected with HIV/AIDS are heterosexuals.[39] with two-thirds of AIDS cases in this region attributed to this route. Sex between men is also a significant route of transmission, even though it is heavily stigmatised and illegal in many areas. HIV transmission through injecting drug use remains rare, except in Bermuda and Puerto Rico.

Within the Caribbean, the country with the highest prevalence of HIV/AIDS is the Bahamas with a rate of 3.2% of adults with the disease. However, when comparing rates from 2004 to 2013, the number of newly diagnosed cases of HIV decreased by 4% over those years. Increased education and treatment drugs will help to decrease incidence levels even more.[40]

Central and South America

The populations of Central and South America have approximately 1.6 million people currently infected with HIV and this number has remained relatively unvarying with having a prevalence of approximately .4%. In Latin America, those infected with the disease have received help in the form of Antiretroviral treatment, with 75% of people with HIV receiving the treatment.[41]

In these regions of the American continent, only Guatemala and Honduras have national HIV prevalence of over 1%. In these countries, HIV-infected men outnumber HIV-infected women by roughly 3:1.

With HIV/AIDS incidence levels rising in Central America, education is the most important step in controlling the spread of this disease. In Central America, many people do not have access to treatment drugs. This results in 8–14% of people dying from AIDS in Honduras. To reduce the incidence levels of HIV/AIDS, education and drug access needs to improve.[42]

In a study of immigrants traveling to Europe, all asymptomatic persons were tested for a variety of infectious diseases. The prevalence of HIV among the 383 immigrants from Latin America was low, with only one person testing positive for a HIV infection. This data was collected from a group of immigrants with the majority from Bolivia, Ecuador and Colombia.[43]

United States

Since the epidemic began in the early 1980s, 1,216,917 people have been diagnosed with AIDS in the US. In 2016, 14% of the 1.1 million people over age 13 living with HIV were unaware of their infection.[44] The most recent CDC HIV Surveillance Report estimates that 38,281 new cases of HIV were diagnosed in the United States in 2017, a rate of 11.8 per 100,000 population.[45] Men who have sex with men accounted for approximately 8 out of 10 HIV diagnoses among males. Regionally, the population rates (per 100,000 people) of persons diagnosed with HIV infection in 2015 were highest in the South (16.8), followed by the Northeast (11.6), the West (9.8), and the Midwest (7.6).[46]

The most frequent mode of transmission of HIV continues to be through male homosexual sexual relations. In general, recent studies have shown that 1 in 6 gay and bisexual men were infected with HIV.[47] As of 2014, in the United States, 83% of new HIV diagnoses among all males aged 13 and older and 67% of the total estimated new diagnoses were among homosexual and bisexual men. Those aged 13 to 24 also accounted for an estimated 92% of new HIV diagnoses among all men in their age group.[48]

A review of studies containing data regarding the prevalence of HIV in transgender women found that nearly 11.8% self-reported that they were infected with HIV.[49] Along with these findings, recent studies have also shown that transgender women are 34 times more likely to have HIV than other women.[47] A 2008 review of HIV studies among transgender women found that 28 percent tested positive for HIV.[50] In the National Transgender Discrimination Survey, 20.23% of black respondents reported being HIV-positive, with an additional 10% reporting that they were unaware of their status.[51]

AIDS is one of the top three causes of death for African American men aged 25–54 and for African American women aged 35–44 years in the United States of America. In the United States, African Americans make up about 48% of the total HIV-positive population and make up more than half of new HIV cases, despite making up only 12% of the population. The main route of transmission for women is through unprotected heterosexual sex. African American women are 19 times more likely to contract HIV than other women.[52]

By 2008, there was increased awareness that young African-American women in particular were at high risk for HIV infection.[53] In 2010, African Americans made up 10% of the population but about half of the HIV/AIDS cases nationwide.[54] This disparity is attributed in part to a lack of information about AIDS and a perception that they are not vulnerable, as well as to limited access to health-care resources and a higher likelihood of sexual contact with at-risk male sexual partners.[55]

Since 1985, the incidence of HIV infection among women had been steadily increasing. In 2005 it was estimated that at least 27% of new HIV infections were in women.[56] There has been increasing concern for the concurrency of violence surrounding women infected with HIV. In 2012, a meta-analysis showed that the rates of psychological trauma, including Intimate Partner Violence and PTSD in HIV positive women were more than five times and twice the national averages, respectively.[57] In 2013, the White House commissioned an Interagency Federal Working Group to address the intersection of violence and women infected with HIV.[58]

There are also geographic disparities in AIDS prevalence in the United States, where it is most common in the large cities of California, esp. Los Angeles and San Francisco and the East Coast, ex. New York City and in urban cities of the Deep South.[59] Rates are lower in Utah, Texas, and Northern Florida.[59] Washington, D.C., the nation's capital, has the nation's highest rate of infection, at 3%. This rate is comparable to what is seen in west Africa, and is considered a severe epidemic.[60]

In the United States in particular, a new wave of infection is being blamed on the use of methamphetamine, known as crystal meth. Research presented at the 12th Annual Retrovirus Conference in Boston in February 2005 concluded that using crystal meth or cocaine is the biggest single risk factor for becoming HIV+ among US gay men, contributing 29% of the overall risk of becoming positive and 28% of the overall risk of being the receptive partner in anal sex.[61]

In addition, several renowned clinical psychologists now cite methamphetamine as the biggest problem facing gay men today, including Michael Majeski, who believes meth is the catalyst for at least 80% of seroconversions currently occurring across the United States, and Tony Zimbardi, who calls methamphetamine the number one cause of HIV transmission, and says that high rates of new HIV infection are not being found among non-crystal users. In addition, various HIV and STD clinics across the United States report anecdotal evidence that 75% of new HIV seroconversions they deal with are methamphetamine-related; indeed, in Los Angeles, methamphetamine is regarded as the main cause of HIV seroconversion among gay men in their late thirties.[61] The chemical "methamphetamine", in and of itself, cannot infect someone with HIV.

Canada

In 2016, there were approximately 63,100 people living with HIV/AIDS in Canada.[62] It was estimated that 9090 persons were living with undiagnosed HIV at the end of 2016.[62] Mortality has decreased due to medical advances against HIV/AIDS, especially highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). HIV/AIDS prevalence is increasing most rapidly amongst aboriginal Canadians, with 11.3% of new infections in 2016.[62]

Eastern Europe and Central Asia

There is growing concern about a rapidly growing epidemic in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, where an estimated 1.23–3.7 million people were infected as of December 2011, though the adult (15–49) prevalence rate is low (1.1%). The rate of HIV infections began to grow rapidly from the mid-1990s, due to social and economic collapse, increased levels of intravenous drug use and increased numbers of prostitutes. By 2010 the number of reported cases in Russia was over 450,000 according to the World Health Organization, up from 15,000 in 1995 and 190,000 in 2002; some estimates claim the real number is up to eight times higher, well over 2 million. There are predictions that the infection rate in Russia will continue to rise quickly, since education there about AIDS is almost non-existent.[63]

Ukraine and Estonia also have growing numbers of infected people, with estimates of 240,000 and 7,400 respectively in 2018. Also, transmission of HIV is increasing through sexual contact and drug use among the young (<30 years). Indeed, over 84% of current AIDS cases in this region occur in non-drug-using heterosexuals less than 26 years of age.

Western Europe

In most countries of Western Europe, AIDS cases have fallen to levels not seen since the original outbreak; many attribute this trend to aggressive educational campaigns, screening of blood transfusions and increased use of condoms. Also, the death rate from AIDS in Western Europe has fallen sharply, as new AIDS therapies have proven to be an effective (though expensive) means of suppressing HIV.

In this area, the routes of transmission of HIV is diverse, including paid sex, injecting drug use, mother to child, male with male sex and heterosexual sex.[citation needed] However, many new infections in this region occur through contact with HIV-infected individuals from other regions. The adult (15–49) prevalence in this region is 0.3% with between 570,000 and 890,000 people currently infected with HIV. Due to the availability of antiretroviral therapy, AIDS deaths have stayed low since the lows of the late 1990s. However, in some countries, a large share of HIV infections remain undiagnosed and there is worrying evidence of antiretroviral drug resistance among some newly HIV-infected individuals in this region.

Oceania

There is a very large range of national situations regarding AIDS and HIV in this region. This is due in part to the large distances between the islands of Oceania. The wide range of development in the region also plays an important role. The prevalence is estimated at between 0.2% and 0.7%, with between 45,000 and 120,000 adults and children currently infected with HIV.

Papua New Guinea has one of the most serious AIDS epidemics in the region. According to UNAIDS, HIV cases in the country have been increasing at a rate of 30 percent annually since 1997, and the country's HIV prevalence rate in late 2006 was 1.3%.[64]

AIDS and society

In June 2001, the United Nations held a Special General Assembly to intensify international action to fight the HIV/AIDS epidemic as a global health issue, and to mobilize the resources needed towards this aim, labelling the situation a "global crisis".[65]

Regarding the social effects of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, some sociologists suggest that AIDS has caused a "profound re-medicalisation of sexuality".[66][67]

See also

Notes

- ^ Cohen, MS; Hellmann, N; Levy, JA; DeCock, K; Lange, J (April 2008). "The spread, treatment, and prevention of HIV-1: evolution of a global pandemic". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 118 (4): 1244–54. doi:10.1172/JCI34706. PMC 2276790. PMID 18382737.

- ^ "WHO HIV/AIDS Data and Statistics". Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Fact Sheet" (PDF). UNAIDS.org. 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ "UN AIDS DATA2019". UNAIDS.org. 2019. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- ^ Wang, Haidong; Wolock, Tim M; Carter, Austin; Nguyen, Grant; Kyu, Hmwe Hmwe; Gakidou, Emmanuela; Hay, Simon I; Mills, Edward J; Trickey, Adam (1 August 2016). "Estimates of global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and mortality of HIV, 1980–2015: the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". The Lancet HIV. 3 (8): e361–e387. doi:10.1016/s2352-3018(16)30087-x. ISSN 2352-3018. PMC 5056319. PMID 27470028.

- ^ P03022017.pdf

- ^ UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA 2017, HIV and AIDS Estimates

- ^ a b UNAIDS 2011 pg. 40–50

- ^ UNAIDS 2011 pg. 20–30

- ^ "HIV in the United States: At A Glance HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report 2019;24(1)". 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ "Progress towards ending the HIV epidemic in the United Kingdom 2018 report" (PDF). Public Health England. 2018. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ accessdate=13 October 2018

- ^ accessdate=11 November 2018

- ^ HIV and AIDS in Canada : surveillance report to December 31, 2009 (PDF). Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada, Centre for Communicable Diseases and Infection Control, Surveillance and Risk Assessment Division. 2010. ISBN 978-1-100-52141-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 January 2012.

- ^ "HIV pandemic's origins located". University of Oxford. 3 October 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ Hardy, W. David (10 June 2019). Fundamentals of HIV Medicine 2019. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190942496.

- ^ "Global Report Fact Sheet" (PDF). UNAIDS. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 September 2012.

- ^ Barre-Sinoussi, F; Chermann, J.; Rey, F; Nugeyre, M.; Chamaret, S; Gruest, J; Dauguet, C; Axler-Blin, C; Vezinet-Brun, F; Rouzioux, C; Rozenbaum, W (20 May 1983). "Isolation of a T-lymphotropic retrovirus from a patient at risk for acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)". Science. 220 (4599): 868–871. Bibcode:1983Sci...220..868B. doi:10.1126/science.6189183. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 6189183. S2CID 390173.

- ^ Gallo, R.; Sarin, P.; Gelmann, E.; Robert-Guroff, M; Richardson, E; Kalyanaraman, V.; Mann, D; Sidhu, G.; Stahl, R.; Zolla-Pazner, S; Leibowitch, J (20 May 1983). "Isolation of human T-cell leukemia virus in acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)". Science. 220 (4599): 865–867. Bibcode:1983Sci...220..865G. doi:10.1126/science.6601823. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 6601823.

- ^ "HIV current status". UNAIDS. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ "Country Comparison :: HIV/AIDS - adult prevalence rate — The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". cia.gov. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g "UNAIDS World Aids Day Report" (PDF). publisher. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

The ranges define the boundaries within which the actual numbers lie, based on the best available information.

- ^ UNAIDS, WHO (2007). "2007 AIDS epidemic update" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2008. Retrieved 26 May 2008.

- ^ "Life expectancy at birth, total (years)". worldbank.org.

- ^ Dwyer-Lindgren, Laura; Cork, Michael A.; Sligar, Amber; Steuben, Krista M.; Wilson, Kate F.; Provost, Naomi R.; Mayala, Benjamin K.; VanderHeide, John D.; Collison, Michael L. (15 May 2019). "Mapping HIV prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa between 2000 and 2017". Nature. 570 (7760): 189–193. Bibcode:2019Natur.570..189D. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1200-9. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 6601349. PMID 31092927.

- ^ Timberg, Craig (2 March 2007). "Speeding HIV's Deadly Spread". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- ^ a b Samuels, Fiona (2009) HIV and emergencies: one size does not fit all London: Overseas Development Institute

- ^ Chigwedere P, Seage GR, Gruskin S, Lee TH, Essex M (October 2008). "Estimating the Lost Benefits of Antiretroviral Drug Use in South Africa". Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 49 (4): 410–415. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818a6cd5. PMID 19186354. S2CID 11458278.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lay-url=ignored (help) - ^ Nattrass N (February 2008). "Estimating the Lost Benefits of Antiretroviral Drug Use in South Africa". African Affairs. 107 (427): 157–76. doi:10.1093/afraf/adm087.

- ^ a b c "Miles to go—closing gaps, breaking barriers, righting injustices". unaids.org. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d "AIDSinfo | UNAIDS". aidsinfo.unaids.org. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- ^ "UNAIDS data 2018". unaids.org. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- ^ "WHO | Antiretroviral therapy (ART) coverage among all age groups". WHO. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- ^ a b c Fiona Samuels and Sanju Wagle 2011. Population mobility and HIV and AIDS: review of laws, policies and treaties between Bangladesh, Nepal and India Archived 20 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine. London: Overseas Development Institute

- ^ Gangcuangco LM, Tan ML, Berba RP (September 2013). "Prevalence and risk factors for HIV infection among men having sex with men in Metro Manila, Philippines" (PDF). Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 44 (5): 810–816. PMID 24437316.

- ^ Gangcuangco, et al. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "HIV and AIDS in Asia & the Pacific regional overview | Avert". avert.org. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ^ UNAIDS, WHO (2005). AIDS epidemic update 2005.

- ^ Voelker, Rebecca (2001). "HIV/AIDS in the Caribbean". JAMA. 285 (23): 2961–3. doi:10.1001/jama.285.23.2961. PMID 11410079.

- ^ "HIV and AIDS in the Caribbean | Avert". avert.org. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ^ "Latin America and the Caribbean | UNAIDS". unaids.org. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ^ Carrillo, Karen Jaunita (30 September 2004). "HIV/AIDS training for C. America Garifuna health care workers". The New York Amsterdam News – via EBSCOhost.

- ^ Monge-Maillo, Begoña; López-Vélez, Rogelio; Norman, Francesca F.; Ferrere-González, Federico; Martínez-Pérez, Ángela; Pérez-Molina, José Antonio (1 April 2015). "Screening of Imported Infectious Diseases Among Asymptomatic Sub-Saharan African and Latin American Immigrants: A Public Health Challenge". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 92 (4): 848–856. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.14-0520. ISSN 0002-9637. PMC 4385785. PMID 25646257.

- ^ "HIV in the United States: At A Glance HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report 2019;24(1)". CDC. 2019.

- ^ "HIV Surveillance | Reports| Resource Library | HIV/AIDS | CDC". cdc.gov. 7 November 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ "HIV in the United States: At A Glance". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. USA.gov. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ a b Campaign, Human Rights. "HIV and the LGBT Community | Human Rights Campaign". Human Rights Campaign. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ^ "HIV Among Gay and Bisexual Men" (PDF). Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ^ "Estimating HIV Prevalence and Risk Behaviors of Transgender Persons in the United States: A Systematic Review". AIDS and Behavior.

- ^ "CDC FACT SHEET: Today's HIV/AIDS Epidemic" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. USA.Gov. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "Injustice at Every Turn: A Look at Black Respondents in the National Transgender Discrimination Survey" (PDF). National Black Justice Coalition, National Center for Transgender Equality, and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ "Kaiser Daily HIV/AIDS Report Summarizes Opinion Pieces on U.S. AIDS Epidemic". The Body – The Complete HIV/AIDS Resource. 20 June 2005. Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- ^ "Report: Black U.S. AIDS rates rival some African nations". cnn.com.

- ^ "DTL&feed=rss. news_politics White House summit on AIDS' impact on black men[dead link]". San Francisco Chronicle. 3 June 2010.

- ^ Arya M, Behforouz HL, Viswanath K (9 March 2009). "African American Women and HIV/AIDS: A National Call for Targeted Health Communication Strategies to Address a Disparity". The AIDS Reader. 19 (2): 79–84, C3. PMC 3695628. PMID 19271331.

- ^ CDC. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, 2005. Vol. 17. Rev ed. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC: 2007:1–46. Available at http://www.cdc Archived 20 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine. gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/. Accessed 28 June 2007.

- ^ Machtinger EL, Wilson TC, Haberer JE, Weiss DS (November 2012). "Psychological trauma and PTSD in HIV-positive women: a meta-analysis". AIDS Behav. 16 (8): 2091–100. doi:10.1007/s10461-011-0127-4.[http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/773935 (inactive 6 June 2020). PMID 22249954.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of June 2020 (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 November 2016. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2009. Retrieved 30 October 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "AIDS epidemic in Washington, DC". pri.org. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- ^ a b "Life or Meth". Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- ^ a b c "The epidemiology of HIV in Canada". CATIE. 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ Center for Strategic and International Studies. http://csis.org/program/hivaids

- ^ Health Profile: Papua New Guinea Archived 14 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine. United States Agency for International Development (September 2008). Accessed 20 March 2009.

- ^ United Nations Special Session on HIV/AIDS. New York, 25–27 June 2001 – http://www.un.org/ga/aids/conference.html

- ^ Aggleton, Peter; Parker, Richard Bordeaux; Barbosa, Regina Maria (2000). Framing the sexual subject: the politics of gender, sexuality, and power. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21838-3. p.3

- ^ Vance, Carole S. (1991). "Anthropology Rediscovers Sexuality: A Theoretical Comment". Social Science and Medicine. 33 (8): 875–884. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(91)90259-F. PMID 1745914.

- References

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) (2011). Global HIV/AIDS Response, Epidemic update and health sector progress towards universal access (PDF). Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

Further reading

- Global report with AIDS info database from UNAIDS

- Global, regional and national profiles from Avert.org

- The River: A Journey to the Source of HIV and AIDS Edward Hooper (1999) ISBN 978-0-316-37261-9

- IASSTD & AIDS – Indian Association for the Study of Sexually Transmitted Diseases & AIDS

- AIDS.gov – The U.S. Federal Domestic HIV/AIDS Resource