Great Recycling and Northern Development Canal

The Great Recycling and Northern Development (GRAND) Canal of North America or GCNA is a water management proposal designed by Newfoundland engineer and visionary Thomas Kierans to alleviate North American freshwater shortage problems. It proposed damming James Bay, using the techniques of the Zuiderzee/IJsselmeer, to prevent its waters mixing with the salt water of Hudson Bay to the north. This would produce an enormous freshwater lake, some of which would be pumped south into Georgian Bay where it would increase the freshwater levels of the lower Great Lakes. The flow would be the equivalent to 2.5 Niagara Falls.

The plan was promoted by Kierans from 1959 until his death in 2013 and since by his son, Michael Kierans. This plan arose as water quality issues threatened the Great Lakes and other vital areas in Canada and the United States.[1] Kierans proposed that to avoid a water crisis from future droughts in Canada and the United States, in addition to water conservation, acceptable new fresh water sources had to be found.

During the 1960s and again in the 1980s when Great Lake water levels declined dramatically, there was interest in the GRAND Canal. However, the reluctance of the US and Canadian governments to enter into large scale co-operative international water sharing arrangements and claims of potential negative environmental impact of the proposal have prevented serious consideration of the idea.

Background

In 1959, Canada officially claimed that U.S. expansion of a Chicago diversion from Lake Michigan would harm downstream Canadian areas in the Great Lakes Basin.

The Canadian government further stated that exhaustive studies had indicated no additional sources of freshwater were available in Canada to replace the waters that would be removed from the Great Lakes by the proposed diversion. Kierans disputed the accuracy of the 1959 Canadian government's position and asserted that the GRAND Canal could provide additional fresh water to the Great Lakes.

Waters from the Ogoki River and Longlac are now being diverted into the Great Lakes at a rate equivalent to that taken by the U.S. at the Chicago diversion.[2]

Proposal

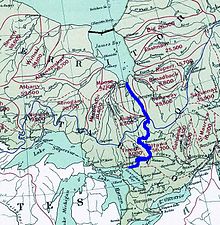

In his GCNA proposal, Kierans asserts that experience in the Netherlands demonstrates that a large new freshwater source can be created in Canada's James Bay by collecting runoff from many adjacent river basins in a sea level, outflow-only dyke-enclosure. The project would capture and make available for recycling the entire outflows of the La Grande, Eastmain, Rupert, Broadback, Nottaway, Harricana, Moose, Albany, Kapiskau, Attawapiskat and Ekwan rivers.[3] Moreover, Kierans claims that the California Aqueduct proves that runoff to James Bay can be beneficially recycled long distances and over high elevations via the GRAND Canal. The GCNA would stabilize water levels in the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River and improve water quality. The GRAND Canal system would also deliver new fresh water from the James Bay dyke-enclosure, via the Great Lakes, to many water deficit areas in Canada and the United States. The project was estimated in 1994 to cost C$100 billion to build and a further C$1 billion annually to operate, involving a string of nuclear reactors and hydroelectric dams to pump water uphill and into other water basins.

Benefits and costs

Kierans argues recycling runoff from a dike-enclosure in Canada's James Bay is not harmful and can bring both nations many useful benefits including:

- More fresh water for Canada and the United States to stabilize Great Lakes/St. Lawrence water levels and to relieve water shortages and droughts in western Canada and in the south-west U.S. and in particular to halt the depletion and start the replenishment of the Ogallala Aquifer (see Water export);

- Improved fisheries and shipping in Hudson Bay. Oceanographer Professor Max Dunbar pointed out in his paper "Hudson Bay has too much fresh water"[4] that as a result of its low salinity Hudson Bay currently "offers no possibilities for commercial fisheries". By recycling the fresh water runoff from James Bay south to the Great Lakes and away from Hudson's Bay the GRAND Canal will increase Hudson Bay's now harmfully low salinity and consequently improve the commercial fisheries. Increasing the salinity of Hudson Bay will also have the benefit of reducing the freeze-over period during the winter and thereby lengthen the navigation season in Hudson Bay;

- Improved Great Lakes water quality due to the increased flows;

- Increased electricity available for alternate uses and lowered user cost of electricity by integrating water transfer energy needs with peak power demand;

- Enhanced flood controls;[5]

- Improved forest fire protection for both nations;[6]

- The construction and operation of the GCNA would provide economic stimulus to create employment and avoid recession. This would be similar to the economic stimulus that the Tennessee Valley Authority development and other public works had in the 1930s to start the recovery from the Great Depression.

According to Kierans, project organization to recycle runoff from James Bay Basin could be like that for the St. Lawrence Seaway. Capital costs for about 160 million users will exceed $100 billion. But, he claims, "before construction is completed, the total value of social, ecologic and economic benefits in Canada and the U.S. will surpass the project's costs."

Developments

The GRAND Canal proposal attracted the attention of former Québec premier Robert Bourassa and former prime minister of Canada Brian Mulroney. By 1985, Bourassa and several major engineering companies endorsed detailed GRAND Canal concept studies;[7] however, these concept studies have not proceeded in part because of opposition based on the potential environmental impact of the plan.

Environmental concerns

Some potential environmental impacts of this proposal that would require study prior to its implementation include:

- Later ice formation, and earlier ice breakup outside the dike corresponding to an opposite change in the fresh waters inside;

- Diminished ecological productivity, possibly as far away as the Labrador Sea;

- Fewer nutrients being deposited into Hudson Bay during spring melts;

- Removal of James Bay's dampening effect on tidal and wind disturbances; and

- Adversely affected migratory bird populations.[8]

The reduced freshwater flow into Hudson Bay will alter the salinity and stratification of the bay, possibly impacting primary production in Hudson Bay, along the Labrador coast, and as far away as the fishing grounds in the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, the Scotian Shelf, and Georges Bank.

If the James Bay dike is built, "Virtually all marine organisms would be destroyed [in the newly formed lake]".[9] Freshwater species would move in, but northern reservoirs tend to fail to produce viable fisheries. The inter-basin connections would be ideal vectors for invasive species to invade new waters.

The construction of a dike across James Bay could negatively impact many mammal species, including ringed and bearded seals, walruses, and bowhead whales, as well as vulnerable populations of polar bears and beluga whales. The impacts would also affect many species of migratory bird, including lesser snow geese, Canada geese, black scoters, brants, American black ducks, northern pintails, mallards, American wigeons, green-winged teals, greater scaups, common eiders, red knots, dunlins, black-bellied, American goldens, and semipalmated plovers, greater and lesser yellowlegs, sanderlings, many species of sandpipers, whimbrels, and marbled godwits, as well as the critically endangered Eskimo curlew.[8]

Social concerns

The project is expected to cost C$100 billion to implement, and a further C$1 billion a year to operate. Most of the water diverted would be exported to the U.S.

In addition, the shoreline communities of Attawapiskat, Kashechewan, Fort Albany, Moosonee and Moose Factory in Ontario, and Waskaganish, Eastmain, Wemindji and Chisasibi in Quebec would be forced to relocate.

Conspiracy theory

In the 1990s, Canadian conspiracy theorists believed the "GRAND Canal" was part of a conspiracy to end Canadian sovereignty and force it into a union with the U.S. and Mexico.[10] Conspiracy theorists believed that forces interested in a North American Union would agitate for Quebec separation, which would then touch off a Canadian civil war and plunge the Canadian economy into a depression. Impoverished Canadians would then look to the canal project and North American Union to revitalize the Canadian economy.[11] Much of the scenario was lifted from Lansing Lamont's 1994 book Breakup: The Coming End of Canada and the Stakes for America.[12]

Allegedly masterminding this conspiracy was Simon Reisman,[13] ostensibly a Freemason.[14]

See also

- Interbasin transfer

- James Bay Project

- California State Water Project

- North American Water and Power Alliance

- Chicago River reversal

- Zuiderzee Works

- South–North Water Transfer Project

- Northern river reversal

References

- ^ Great Lakes water diversion CityMayors.com

- ^ DeCew Falls II Archived 2008-07-05 at the Wayback Machine Ontario Power Generation

- ^ A brief history of the Great Recycling and Northern Development (Grand) Canal project Undercurrents

- ^ Dunbar, Max (1993, May) [1] Centre for Climate and Global Change Research, McGill University

- ^ The GRAND Canal Official Web Site: Proposal

- ^ The GRAND Canal Official Website: Summary

- ^ Bourassa, Robert (1985, May). Power From the North, Prentice Hall of Canada Ltd.

- ^ a b Milko, Robert (1986, December). Potential ecological effects of the proposed GRAND Canal diversion project on Hudson and James Bays. Arctic, 39(4): 316-325.

- ^ Milko, Robert (1986, December). Potential ecological effects of the proposed GRAND Canal diversion project on Hudson and James Bays. Arctic, 39(4): 322.

- ^ The planned destruction of Canada from the Social Credit Party of Canada newspaper the Michael Journal

- ^ Usenet posting from 1996

- ^ Amazon.com: Breakup: The Coming End of Canada and the Stakes for America: Lansing Lamont: Books

- ^ The West By John Frederick Conway

- ^ "Build your own conspiracy theory" Montreal Mirror

External links

- A Brief History of the Great Recycling and Northern Development (GRAND) Canal Project, Undercurrents

- GRAND Canal official website

- Hunter, David (1992) Interbasin water transfers after NAFTA: Is water a commodity or ecological resource? Center for International Environmental Law

- Milko, Robert (1986, December). Potential ecological effects of the proposed GRAND Canal diversion project on Hudson and James Bays. Arctic, 39(4): 316-325.

- Video interview of Thomas Kierans post on Globe and Mail web site.

- Youtube video of Michael Kierans discussing the GRAND Canal on CNN [2]

- A visionary's epiphany about water