James Weldon Johnson Park

| James Weldon Johnson Park | |

|---|---|

James Weldon Johnson Park | |

| |

| Type | Municipal |

| Location | Jacksonville, Florida |

| Coordinates | 30°19′45″N 81°39′33″W / 30.32917°N 81.65917°W[1] |

| Area | 1.54 acres (6,200 m2) |

| Created | 1857 |

| Operated by | City of Jacksonville |

| Visitors | 1 million |

| Status | Open all year |

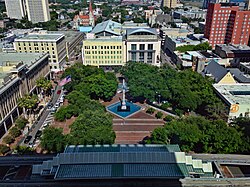

James Weldon Johnson Park is a 1.54-acre (6,200 m2) public park in Downtown Jacksonville, Florida. Originally a village green, it was the first and is the oldest park in the city.[2]

History

Beginnings

The area was established as a public square in 1857 by Isaiah Hart, founder of Jacksonville. After Hart's death in 1861 and the end of the Civil War, the Hart family deeded the land to the city for $10. It was first known as "City Park", then "St. James Park" after the grand St. James Hotel was constructed across the street in 1869. The following year, another major hotel was built across from the park.

The area was renamed Hemming Park in 1899 in honor of Civil War veteran Charles C. Hemming, after he installed a 62-foot (19 m)-tall Confederate monument in the park in 1898.[3] Hemming was born in Jacksonville. He later moved to Colorado Springs, Colorado and became a banker, making a fortune.[1] The memorial is the oldest in the city and was the tallest at the time.[2] An occurrence in February 1896 brought lasting change to St. James Park. At the state reunion of United Confederate Veterans (UCV) in Ocala, Charles C. Hemming announced his plan to erect a memorial in honor of Florida’s Confederate soldiers. Members of the local Robert E. Lee Camp of Confederate Veterans immediately invited Hemming to a reception in Jacksonville, which was attended by many prominent citizens. After moving from St. Augustine to Jacksonville at the age of two, Hemming grew up in the City, and local officials hoped that he would select Jacksonville as the site for the monument.

Hemming viewed several possible locations and expressed a preference for the center of St. James Park, where the fountain stood. Though reluctant to replace the popular fountain, the City’s Board of Public Works later gave its approval.

A committee of the Robert E. Lee Camp managed the memorial project. But newspaper accounts appear to indicate that Hemming personally selected the monument, which was then approved by various committees of the UCV.

George H. Mitchell of Chicago, Illinois – a designer, manufacturer, and contractor for artistic memorials – provided the monument. It cost approximately $20,000, and was a joint gift from Charles Hemming and his wife, Lucy Key Hemming, a native of Texas.

The City moved the fountain to the northwest section of St. James Park, and George Mitchell traveled to Jacksonville and supervised installation of the monument in the spring of 1898, during the Spanish American War. At that time, the Springfield section of the City contained thousands of American troops living in a tent city known as Camp Cuba Libre.

The unveiling ceremony took place on June 16, 1898, and coincided with the reunion in Jacksonville of the UCV’s Florida Division. Hemming donated the monument to the State of Florida, and Governor William D. Bloxham accepted the memorial on behalf of the state.

Though Hemming did not attend the dedication, General Fitzhugh Lee, the nephew of Confederate General Robert E. Lee, was in the reviewing stand, and the grandson of Union General Ulysses S. Grant watched the unveiling from the piazza of the Windsor Hotel. In addition, both northern and southern troops from Camp Cuba Libre attended the ceremony, and much of the oratory concerned the reuniting of the North and South.

The monument rises sixty-two feet from a square foundation. A column, extends up from the base (both made of Vermont granite), and is topped by the bronze figure of a Confederate soldier in winter uniform. He stands at ease, with hands clasping the barrel of his rifle that rests on the ground, and on his cap are the initials, “J.L.I.”, representing the Jacksonville Light Infantry.

Bronze plaques, with images of Southern heroes sculpted in relief, are mounted on three sides of the base: A bust of Confederate General Kirby Smith on the north; a scene of Generals Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson with their drum corps on the west; and a bust of General J.J. Dickinson, commander of the UCV’s Florida Division on the south.

Confederate Memorial in Hemming Plaza On the east side of the base is a plaque with the following inscription, most likely written by Charles Hemming:

TO THE SOLDIERS OF FLORIDA This shaft is by a comrade raised in testimony of his love, recalling deeds immortal, heroism unsurpassed. With ranks unbroken, ragged, starved and decimated, the Southern soldier for duty’s sake, undaunted, stood to the front of the battle until no light remained to illumine the field of carnage, save the luster of his chivalry and courage. Nor shall your glory be forgot, While fame her record keeps, CONFEDERATE MEMORIAL 1861-1865 About Charles C. Hemming: Charles C. Hemming was the son of Englishman John C. Heming (spelled originally with one “m”), who moved to Jacksonville in the mid 1840s, and worked both in the real estate business and as a bookkeeper. He also held a variety of public offices, including town auctioneer and City Councilman, and following his death in 1886, was buried in the Old City Cemetery.

To honor Charles Hemming for his donation of the memorial, the City Council changed the name of St. James Park to Hemming Park on October 26, 1899 (Ordinance E-9). [4]

The Great Fire of 1901 destroyed most of the wooden structures in Jacksonville and many others, too. Hemming's Confederate monument was one of the few structures to survive the fire. The St. James Hotel burned to the ground and the owner did not have the cash to rebuild. In 1910, Jacob and Morris Cohen, who owned a local dry goods company, engaged 34-year-old architect, Henry John Klutho to fast track design and manage the construction of a four-story building to house their store. The name "St. James Building" stuck to the property and the building.

1960s

During the 1960 presidential campaign, John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon both gave speeches at Hemming Park a few hours apart on October 18.[5] President Lyndon B. Johnson delivered a speech in Hemming Park on October 26, 1964.

Because of its high visibility and patronage, the park and surrounding stores were the site of numerous civil rights demonstrations in the 1960s in the African-American effort to end racial segregation in public facilities. At the time, the city's population was about 45% black. Rutledge Pearson, a local high school teacher, and the NAACP organized many students to participate in sit-ins. Rodney Hurst was the president at age 16 of the NAACP Youth Council and years later, said the students were determined to carry out the protests to gain rights of service in stores that gladly accepted .[6]

Pearson and members of the NAACP had met with the city's mayor to ask for his support in integration but were rejected.[7] The sit-ins began on August 13, 1960: students asked to be served at the segregated lunch counters at Morrison's Cafeteria, Woolworths, and other stores, where the black community spent much money in retail purchases. They were denied service and frequently kicked, spit at, and addressed with racial slurs. This pattern continued for two weeks, until the 27th, a day now referred to as Ax Handle Saturday. On that day, a group of 200 "middle-age and elderly white men,"[7] including some members of the Ku Klux Klan, were arming themselves with axe handles and baseball bats. The student protesters were warned but each wanted to go ahead. The armed group entered the store where they started attacking the students. Some of these found sanctuary in Historic Snyder Memorial, then a Methodist church.[8] A couple of youths alerted the "Boomerangs," a group of older black youth, who entered the fray to protect the demonstrators.[8]

Although the organizers had alerted the police when they saw armed men, law enforcement did not intervene until the Boomerangs and other blacks started fighting back to stop the beatings.[7] Fifty people were injured and 62 were arrested, 14 whites and 48 blacks.[6] The day's events were covered by national TV, as well as major newspapers such as the New York Times and Los Angeles Times.[6] Alton Yates, participated as a 24-year-old, but said some of the protesters were as young as 13, and he was shocked to see men beating children. He said the organizers gathered their forces again and continued sit-ins. In addition, committees of blacks and whites met to discuss and resolve racial issues.[7] In April 1961, two leaders of the NAACP Youth Council ate at Woolworth's for a week to prepare the public for integration.[6]

Finally after the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the city completed integration of water fountains, restrooms, and dressing rooms.[9][6] On August 26, 2000, the NAACP, the National Conference for Community and Justice, the Jacksonville Historical Society, the Human Rights Commission, and the Jacksonville Urban League hosted events to commemorate the history and celebrate the city's progress in the 40 years since then.[6]

Master plan

The Downtown Development Authority (DDA) was created in 1970 to reverse white flight, related to suburbanization and development of retail malls, and end urban blight. They hired RTKL Associates Inc., planning consultants from Baltimore, Maryland to study Jacksonville's situation. Their recommendations were incorporated into the 1971 Downtown Master Plan, using the idea of creating a Pedestrian mall surrounded by a transportation loop and abundant free parking. Another plan component was a group of elevated walkways that would permit shoppers to avoid traffic while moving from the retail core to the riverfront, which would contain a park, convention center including hotel, an exhibition center, Sears Department Store, and a high-rise containing financial offices.[10] The plan was supposed to be completed within 20 years, but many components were never implemented.

Bust

By the mid-1970s, the image of the park had changed. Because the downtown had been invaded by thousands of starlings, the city had removed shade trees to drive the invaders from the park. The City renovated the park in 1977 at a cost of $648,000,[10] converting it into a concrete/brick-paved square and changing the name to Hemming Plaza. The second phase of city redevelopment was budgeted at $2.2 million, but was delayed in 1979. The money was used to construct a University Boulevard overpass of the rail yard adjacent to Philips Highway. Money was again budgeted in 1981, but was used instead to widen 103rd Street. In 1984, the project began, and lasted over two years.[10] By this time, the city's big retailers had already built new stores at the malls to meet suburban demand. The last three major stores closed their downtown locations. The empty storefronts attracted the homeless and the 1971 master plan became irrelevant.[5]

Rebuilding

The Federal Government spent $84 million for the John Milton Bryan Simpson United States Courthouse, which broke ground in 2000 and opened in 2003, across from the Plaza. Over $162 million was invested by the city in the buildings surrounding Hemming Plaza, including:[5]

- St. James Building: $24 million renovation for a new City Hall

- New Downtown Library & parking garage: $100 million

- Ed Ball Building: $25 million renovation for city government office building

- Jacksonville Museum of Contemporary Art: $1.5 million for renovation

- Haverty's Building: $10 million renovation for a new City Hall Annex

- Snyder Memorial Church Building: $1.3 million for renovation

A life-size cast bronze statue of U.S. Rep. Charles Edward Bennett, who served Northeast Florida in Congress for 44 years, was installed on a granite base in Hemming Plaza on April 23, 2004.[11]

2010s to present

In September 2014, the city of Jacksonville entered into a public-private agreement with the nonprofit organization, Friends of Hemming Park, to manage the park. The organization is charged with revitalizing and programming the square. The 501(c)3 nonprofit organization was created by community leaders and members of The Cultural Council of Jacksonville, and Downtown Vision, Inc.[12]

The first Wednesday of every month, the ark is converted into the centerpiece of Jacksonville's Downtown Art Walk.

On June 9, 2020, the park's Confederate monument and commemorative plaque were taken down during local George Floyd protests after 122 years in the center of the park and a three-year Take ‘Em Down Jax Confederate monument removal campaign.[13][14][15]

On August 11, 2020 the Jacksonville City Council voted to change the name of the park to James Weldon Johnson Park, after one of Jacksonville's most famous and accomplished residents, James Weldon Johnson.[16]

References

- ^ a b Waymarking: Confederate Memorial - Hemming Plaza - Jacksonville, FL

- ^ a b City of Jacksonville website: Recreation and Community Services-Hemming Plaza Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ City of Jacksonville: Public Information-Photo Archive

- ^ http://www.scv-kirby-smith.com

- ^ a b c Floridas Times-Union: May 28, 2007-New life in vision for Hemming by Charlie Patton

- ^ a b c d e f Alliniece T. Andino, "40 years ago this weekend, Jacksonville gave itself a national reputation for violence" Archived 2012-06-06 at the Wayback Machine, Florida Times-Union, 25 August 2000

- ^ a b c d Alton Yates, "Civil rights" Archived 2008-12-01 at the Wayback Machine, Florida Times-Union, 21 February 1999

- ^ a b Charlie Patton, "Discrimination in all its forms must be axed" Archived 2008-11-22 at the Wayback Machine, Florida Times-Union, 24 August 2000

- ^ Gil Wilson, "St. Augustine Civil Rights 1960-1965" , Dr. Bronson Tours

- ^ a b c [1], Florida Times-Union,11 September 2009, "Visions of Yesteryear: The 1971 Downtown Master Plan"

- ^ "Florida Times-Union: April 16, 2004- Life-size likeness of Bennett comes to Hemming Plaza by Jessie-Lynne Kerr". Archived from the original on August 12, 2011. Retrieved January 9, 2009.

- ^ Patterson, Steve. "Changes at Hemming Park starting next month, says group handling makeover," jacksonville.com, 11 Nov. 2014. Accessed 10 June 2020.

- ^ "Czachor, Emily. "Jacksonville Mayor Announces Plans to Remove City's Confederate Monuments, Rename Memorial Sites," Newsweek.com, 9 June 2020. Accessed 9 June 2020.

- ^ Orlandini, Tina.“From Confederate Park to Jackson Square, Fight White Supremacy Everywhere!” 13 Apr. 2019, NolaWorkers.org (cached). Accessed 10 June 2020.

- ^ Take Em Down Jax website. Accessed 10 June 2020.

- ^ Corley Peel; Jenese Harris (August 11, 2020). "Council OKs renaming Hemming Park after James Weldon Johnson". News4Jax.com. Retrieved 2020-08-12.